3. How do we identify basic emotions in animals, and which animals can be said to have them?

(a) Which basic emotions do animals have?

Deficient methodologies for distinguishing the emotions

Before discussing how we should differentiate animal emotions, I would like to explain why certain popular methods of distinguishing human emotions are unsuitable when applied to animals.

Linguistic analysis supports the existence of a short list of basic emotions. Most people, when asked to name the emotions they feel, mention love, anger, fear, sorrow and joy. Other emotions figure in less than 20% of responses (Panksepp, 1998, p. 46). The chief problem with a linguistic approach is that it cannot be applied to non-human animals. Another reason why language may be an unreliable guide to animal emotions is that some of the the emotions that have been proposed for animals by scientists (e.g. eagerness, play and nurturance) are not generally described as emotions.

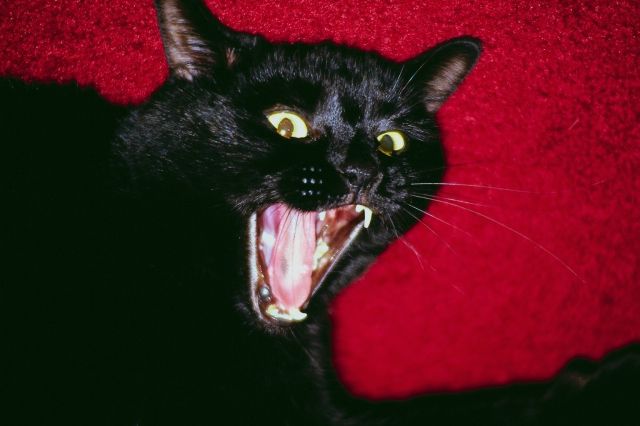

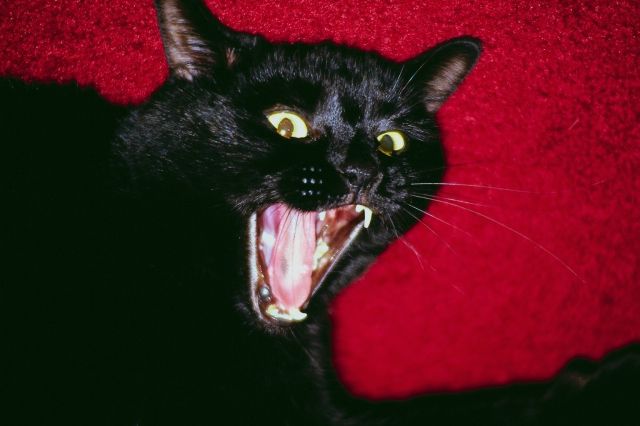

Taxonomies of emotions based on facial analysis, starting with the work of Paul Ekman, have shown that six emotions - surprise, happiness (or joy), anger, fear, disgust and sadness (or distress) - have facial expressions that are universal across all cultures and can be clearly recognised in photos (Le Doux, 1998, p. 113; Evans, 2001, p. 7). However, most people would not consider surprise or disgust to be "proper" emotions. Additionally, Ekman's research focuses on only one species of animal: Homo sapiens. Panksepp (1998) argues that facial expression is a poor indicator of emotion in other animals:

Although in humans and some related primates the face is an exquisitely flexible communicative device, this is not the case for most other mammals, which exhibit clear emotional behaviors but less impressive facial dynamics. Although most animals exhibit open-mouthed, hissing-growling expressions of rage, and some show an openmouthed play/laughter display, they tend to show little else on their faces (1998, pp. 46-47).

Bodily indicators might seem to be a good general criterion for distinguishing animal emotions, as they could be reliably measured by sensors attached to an animal's body. However, as we saw above, this method of differentiating emotions fails to take account of their intentional objects.

How a neurophysiological approach to the emotions allows us to distinguish them according to their generic intentional objects

Since we have argued that each kind of emotion has its own generic intentional object which makes it what it is, and explains what it is about as well as what it is for, it would make sense to distinguish between animal emotions by identifying their respective objects. However, such a proposal faces three problems. Fortunately, a neurophysiological account resolves all of them.

First, it is possible for an animal to have different emotions towards the same object on separate occasions. For instance, an animal may fear a certain individual on one occasion and happily play with the same individual on another occasion.

A neurophysiological approach to the emotions resolves this paradox. An animal may indeed experience two different emotions towards the same physical object on separate occasions, because it may instantiate two different kinds of environmental challenge, and thus two distinct generic intentional objects. Thus a primate may fear an individual it knows, while (s)he is exhibiting a sudden burst of rage, but on other occasions enjoy playing with the same animal. (Of course, the complex human phenomenon of feeling mixed emotions - e.g. love and hate - towards the same individual simultaneously cannot be explained in this fashion.)

Second, we still have to account for emotions that have no intentional object, such as an ill-defined feelings of depression or the undirected emotional states that can be induced by removing parts of animals' brains. Surgical removal of cortical regions makes animals exhibit symptoms of rage which is not always directed at an appropriate target - sometimes, it appears to lack an intentional object - although Panksepp (1998, p. 79) suggests that the animals' lack of directed behaviour simply reflects their disorientation. Of course, one could argue that even in these situations, the kind of emotion experienced still has a generic intentional object. But this begs the question: how do we distinguish emotions according to their various kinds?

Finally, an emotion may have an intentional object which is real but inappropriate, such as when one fears mice or the number 13. What makes these inappropriate emotions of the same kind as their appropriate counterparts?

On a neurophysiological account, particular cases where an animal feels an emotion that is about nothing at all (an object-less emotion that may be naturally or articially induced), or nothing that merits the kind of response shown (inappropriate emotions) still qualify as bona fide instances of their kind, because they are accompanied by the same internal brain states as appropriate expressions of these emotions, and generate similar bodily responses. In these anomalous cases, the emotions felt by the animal are genuine, but the challenge they originally evolved to meet is absent.

What kinds of emotions do animals have?

The brain of every species of mammal contains various basic emotional systems. Panksepp (1998, pp. 48-49)defines these emotion systems in terms of the following features:

The first, second and fifth features are particularly relevant to my proposed method for classifying emotions according to their kinds. A suite of sensory stimuli that trigger identical unconditional responses in one of the emotion systems in an animal's brain all instantiate the same kind of environmental challenge that the animal has to deal with - i.e. its generic intentional object. The instinctive motor outputs triggered by the inputs are the animal's first line of defence. The fact that they can be subsequently modulated by cognitive inputs, means that provided the system satisfies the cognitive requirements for intentional agency (specified in chapter two), the system's response can be described as genuinely emotional and not merely reflexive.

Conclusion E.16 The emotion systems described by Panksepp (1998) correspond to basic kinds of animal emotions. The environmental challenge each system evolved to meet is the generic intentional object of the corresponding emotion.

Panksepp (1998) summarises the research to date on these systems:

There is good biological evidence for at least seven innate emotional systems ingrained within the mammalian brain (1998, p. 47).

"In the vernacular", writes Panksepp, the seven emotional systems include "fear, anger, sorrow, anticipatory eagerness, play, sexual lust, and maternal nurturance" (1998, p. 47). The first four systems are "evident in all mammals soon after birth" (1998, p. 54, italics mine), because the relevant neural circuits lie below the cortex, at a deeper level where the similarities between mammals are most profound. The neural circuits for our emotional systems are actually very ancient, since they arose in response to persistent external environmental challenges. The three special purpose systems - sexual LUST, maternal CARE and PLAY - are engaged only at certain times in mammals' life-cycles, and are not as clearly understood.

The classification of eagerness, play and nurturance as emotional states will strike many readers as odd. However, it makes good sense to do so if they motivate us to act as other emotions do. Panksepp also acknowledges the existence of many more affective feelings (e.g. pain, hunger), but argues that they do not qualify as basic emotional systems because they do not meet all the above criteria (1998, p. 47).

The seven emotion systems are summarised in the table below. (The capitals are Panksepp's.) More detailed information relating to accompanying bodily states and brain circuitry can be found in an Appendix.

Table 3.1 - Emotion Systems identified to date in Mammals (based on Panksepp, 1998)

| Emotion System: FEAR system.

Animal Emotions corresponding to this system: Fear, anxiety, alarm and foreboding

Corresponding Environmental Challenge (generic intentional object): Pain and the threat of destruction

Motivation: Avoiding the threat of bodily harm

Characteristic behaviour: Freezing (mild intensity); flight (high intensity); scanning and vigilance Notes:

|

| Emotion System: RAGE system

Animal Emotions corresponding to this system: Rage, anger

Corresponding Environmental Challenge (generic intentional object): Events that restrict the animal's freedom (physical restraint or irritation of the animal's body surface) or access to resources (e.g. an invasion of the animal's territory)

Motivation: The need to compete effectively for environmental resources.

Characteristic behaviour: Tendency to strike out at, attack, bite or fight the offending agent (a living creature). Notes:

|

| Emotion System: PANIC system

Animal Emotions corresponding to this system: Loneliness, panic, grief

Corresponding Environmental Challenge (generic intentional object): Social loss

Motivation: The urge to be reunited with companions after separation, which helps to create social bonding

Characteristic behaviour: Cries of distress when separated from caregiver

Notes: PANIC is distinct from FEAR. PANIC is thought to be linked with an animal's distress when separated from a socially significant other (e.g. its mother). |

| Emotion System: Exploratory, appetitive SEEKING system

Animal Emotions corresponding to this system: Anticipatory eagerness

Corresponding Environmental Challenge (generic intentional object): Positive environmental incentives such as food, water, sex and warmth.

Motivation: The need for food, water, sex and warmth.

Characteristic behaviour: Stimulus-bound appetitive behaviour: forward locomotion, sniffing, and investigating, mouthing and manipulating objects in the animal's environment. Also self-stimulation - a tendency to engage in events that increase the animal's arousal. Notes:

|

| Emotion System: PLAY (special purpose system)

Animal Emotions corresponding to this system: Play

Corresponding Environmental Challenge (generic intentional object): Opportunity for rough-and-tumble play with conspecifics

Motivation: The need for social interaction

Characteristic behaviour: Rough-and-tumble (RAT) play between juveniles or between parent (usually the mother) and offspring. RAT play includes pinning and dorsal contacts, but varies widely among mammals. Solitary running, jumping, prancing and rolling in herbivores may also represent a form of play. Also laughter (humans) or very high-frequency chirping (rats). Notes: The mammalian brain also contains one or more pleasure systems that correspond to the alleviation of bodily imbalances and a return to an optimal level of functioning. The location and number of the brain's pleasure systems remains unknown. |

| Emotion System: LUST (special purpose system)

Animal Emotions corresponding to this system: Sexual desire

Corresponding Environmental Challenge (generic intentional object): Opportunity to procreate

Motivation: The need to procreate

Characteristic behaviour: Males: courting, territorial marking and mounting. |

| Emotion System: Maternal CARE (special purpose system)

Animal Emotions corresponding to this system: Nurturance (parental love)

Corresponding Environmental Challenge (generic intentional object): Offspring requiring maternal care

Motivation: The need to care for one's offspring

Characteristic behaviour: Responsiveness to distress signals by offspring. Nursing offspring and providing them with warmth and shelter (e.g. a nest). Gathering offspring together. |

The mammalian brain also contains one or more pleasure systems that correspond to the alleviation of bodily imbalances and a return to an optimal level of functioning. However, the location and number of the brain's pleasure systems remains unknown (Panksepp, 1998, pp. 181-185). Because the list of basic emotions described above is not exhaustive, the supposition that only these emotions correspond to natural kinds is unwarranted.

It should also be stressed that neurological criteria alone cannot establish the presence of mental states such as emotions. To show this, it has to be demonstrated that each of the emotion systems described above can motivate intentional agency (Conclusion E.2). However, since mammals are certainly capable of intentional agency (as argued in chapter two) we can provisionally assume that they possess the seven-plus kinds of emotions described by Panksepp. Arguments that some of these emotions presuppose "higher" mental states unique to human beings are addressed below.

Conclusion E.17 All mammals possess at least seven distinct kinds of emotions, whose neural circuitry is well-defined. These seven emotions can motivate intentional acts which promote the telos of a mammal in different ways. Each kind of emotion has a different generic intentional object.

While Panksepp's approach to the emotions avoids anthropocentrism, it remains very focused on the most studied animals: mammals. I propose to use it as a starting point, bearing in mind the dangers of generalising to other animals.

(b) Which Animals Have Emotions?

Some of the brain's emotional architecture appears to be very old. A neurophysiological approach to emotions suggests that some are common to all vertebrates (and possibly other animals), while others may be unique to mammals and birds.

Panksepp (1998, pp. 42-43, 48-51, 70-79) uses a refined version of Maclean's model of the triune brain for illustrative purposes, describing it as an "informative perspective" (1998, p. 43) which "provides a useful overview" (1998, p. 70), while conceding that it is a "didactic simplification from a neuroanatomical point of view" (1998, p. 43). The deepest layer of the forebrain, known as the basal ganglia, is where behavioural responses related to seeking, fear, anger and sexual lust originate. This region is well-defined in all vertebrates.

Conclusion E.18 It is likely that all vertebrates share the (conscious or unconscious) emotions of fear, anger and sexual desire.

The next, loosely defined layer is commonly called the limbic system - a term attacked as outdated by LeDoux (1998, pp. 98-103) but defended as a useful heuristic concept by Panksepp (1998, pp. 57, 71, 353). (Both authors agree that certain specific structures in the limbic system serve important functions relating to the emotions.) This region of the brain contains neural programs relating to social emotions such as maternal care, social bonding (companionship), separation distress, and playfulness (Panksepp, 1998, p. 71). The limbic system is of similar relative size across all mammals, but is much smaller in reptiles.

Conclusion E.19 The social emotions, such as parental care, social bonding (companionship), separation distress, and playfulness, are likely to be absent in fish and amphibians.

Surrounding the limbic system is the neocortex, which Panksepp describes as the "storehouse of our cognitive skills". This region is most developed in human beings, but is not where feelings originate: "We cannot precipitate emotional feelings by artificially activating the neocortex either electrically or neurochemically" (1998, p. 43), whereas subcortical stimulation of specific areas can induce anger, fear, curiosity, hunger and nausea in mammals (1998, p. 79).

Conclusion E.20 There are no basic kinds of emotions that are unique to human beings. The only emotions that are specific to human beings are those whose cognitive requirements are beyond the capacities of other animals.

It is hard to draw conclusions for invertebrates, as their brains have a very different layout. For instance, the amygdala, which which is thought to be responsible for the emotional evaluation of stimuli (Moren and Balkenius, 2000), is confined to vertebrates (Panksepp, personal communication, 11 April 2004). However, LeDoux claims that invertebrates "do the same thing with other circuits" (personal communication, 13 April 2004). Below, I propose criteria for identifying each kind of emotion, which are applicable to all animals.

(c) A general strategy for identifying occurrences of basic emotions in animals

Earlier, we argued that any positive or negative internal state that is capable of motivating animals acting intentionally is a genuine emotion (Conclusion E.2). It was argued in chapter two that operant conditioning, spatial learning, tool-making or social learning are all forms of intentional agency. This suggests one method of identifying genuine emotional states in animals.

Conclusion E.21 An animal which can be motivated to undergo operant conditioning, spatial learning, tool-making or social learning in pursuit or avoidance of one of the motivators described in Table 3.1 is experiencing a mental state: the basic emotion corresponding to that motivator.

However, since each basic emotion is mediated by an "emotion system" in the animal's brain that responds specifically to the relevant motivator, the emotion cannot be identified in an animal using behavioural criteria alone. An underlying brain system, specific to that motivator, must also be identified:

Conclusion E.22 In order to conclusively establish that an animal is indeed undergoing a basic emotion, an emotion system in the animal's brain and/or nervous system has to be identified, which responds specifically to the relevant motivator.

Scientists customarily describe these motivators as "rewards" and "punishments", which suggests that there is a single motivational pleasure-pain axis. I propose that there are in fact several axes - a fear axis, an anger axis, and a desire axis, among others - and thus several different ways to motivate animals undergoing operant conditioning and other forms of agent-centred learning.

For example, an animal's ability to undergo operant conditioning in order to avoid a noxious or dangerous stimulus, strongly suggests that it is being motivated by fear. (The discovery of a circuit in the animal's brain or nervous system that responds specifically to danger would confirm this.) We saw in a case study in chapter two that the fruit fly Drosophila is capable of undergoing operant conditioning, to avoid being fried by a heat beam. The term "fear" could be appropriately applied here, even if phenomenological consciousness is absent.

Conclusion E.23 The emotion of fear is likely to occur in insects capable of operant conditioning (e.g. fruit flies).

Spatial learning, tool-making and social learning provide other settings in which fear can be identified behaviourally (and subsequently confirmed neurologically). An animal that learns by its own efforts how to navigate its way around a dangerous location, or how to use a tool in order to repel something dangerous, or how to manipulate the behaviour of others in its group, in order to reduce the risk of danger, can properly be said to be motivated by fear. (Of course, unlearned fears are no less mentalistic than those felt towards objects we have learned to fear. From an epistemological perspective, however, we can only identify unlearned fears as mental states in animals that are capable of undergoing operant conditioning or some other kind of learning that requires mental states.)

Similar considerations apply to the other basic emotions, as shown in the table below.

Table 3.2 Behavioural criteria for identifying intentional agency associated with each of the basic animal emotions

| Kind of Emotion | How manifested in Intentional Agency (general description) | How manifested in Operant conditioning | How manifested in Spatial Navigation | How manifested in Tool Use | How manifested in Social learning |

| FEAR | Controlling and modifying one's behaviour in order to avoid danger | Ability to modify one's bodily movements in order to avoid danger | Ability to modify one's route in order to avoid danger | Ability to manipulate objects in order to avoid danger | Ability to model one's behaviour on others in order to avoid danger |

| General experimental strategy for identifying the occurrence of FEAR | Would the experiment be ethical? No (see below). | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its bodily movements in order to avoid a predator or a noxious stimulus | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its route in order to avoid a predator or a noxious stimulus | Place an animal in a situation where it has to manipulate some object in order to avoid a predator or a noxious stimulus | Place an animal in a situation where it has to model its behaviour on another animal in order to avoid a predator or a noxious stimulus |

| RAGE or anger | Controlling and modifying one's behaviour in order to get an opportunity to attack an offending agent/object | Ability to modify one's bodily movements in order to get an opportunity to attack an offending agent/object | Ability to modify one's route in order to get an opportunity to attack an offending agent/object | Ability to manipulate objects in order to get an opportunity to attack an offending agent/object | Ability to model one's behaviour on others in order to get an opportunity to attack an offending agent/object |

| General experimental strategy for identifying the occurrence of RAGE | Would the experiment be ethical? No (see below). | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its bodily movements in order to get the opportunity to attack an offending agent/object | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its route in order to get the opportunity to attack an offending agent/object | Place an animal in a situation where it has to manipulate some object in order to get the opportunity to attack an offending agent/object | Place an animal in a situation where it has to model its behaviour on another animal in order to get the opportunity to attack an offending agent/object |

| Anticipatory Eagerness (SEEKING) | Controlling and modifying one's behaviour in order to attain an attractive object | Ability to modify one's bodily movements in order to attain an attractive object | Ability to modify one's route in order to attain an attractive object | Ability to manipulate objects in order to attain an attractive object | Ability to model one's behaviour on others in order to attain an attractive object |

| General experimental strategy for identifying the occurrence of SEEKING | Would the experiment be ethical? Yes. | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its bodily movements in order to attain an attractive object | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its route in order to attain an attractive object | Place an animal in a situation where it has to manipulate some object in order to attain an attractive object | Place an animal in a situation where it has to model its behaviour on another animal in order to attain an attractive object |

| PANIC | Controlling and modifying one's behaviour in order to obtain comforting social contact | Ability to modify one's bodily movements in order to obtain comforting social contact | Ability to modify one's route in order to obtain comforting social contact | Ability to manipulate objects in order to obtain comforting social contact | Ability to model one's behaviour on others in order to obtain comforting social contact |

| General experimental strategy for identifying the occurrence of PANIC | Would the experiment be ethical? No (see below). | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its bodily movements in order to obtain comforting social contact | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its route in order to obtain comforting social contact | Place an animal in a situation where it has to manipulate some object in order to obtain comforting social contact | Place an animal in a situation where it has to model its behaviour on another animal in order to obtain comforting social contact |

| LUST | Controlling and modifying one's behaviour in order to get an opportunity to satisfy sexual urges | Ability to modify one's bodily movements in order to get an opportunity to satisfy sexual urges | Ability to modify one's route in order to get an opportunity to satisfy sexual urges | Ability to manipulate objects in order to get an opportunity to satisfy sexual urges | Ability to model one's behaviour on others in order to get an opportunity to satisfy sexual urges |

| General experimental strategy for identifying the occurrence of LUST | Would the experiment be ethical? Yes. | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its bodily movements in order to get an opportunity to satisfy its sexual urges | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its route in order to get an opportunity to satisfy its sexual urges | Place an animal in a situation where it has to manipulate some object in order to get an opportunity to satisfy its sexual urges | Place an animal in a situation where it has to model its behaviour on another animal in order to get an opportunity to satisfy its sexual urges |

| Maternal CARE | Controlling and modifying one's behaviour in order to get an opportunity to nurture offspring | Ability to modify one's bodily movements in order to get an opportunity to nurture offspring | Ability to modify one's route in order to get an opportunity to nurture offspring | Ability to manipulate objects in order to get an opportunity to nurture offspring | Ability to model one's behaviour on others in order to get an opportunity to nurture offspring |

| General experimental strategy for identifying the occurrence of CARE | Would the experiment be ethical? No (see below). | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its bodily movements in order to get an opportunity to nurture its offspring | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its route in order to get an opportunity to nurture its offspring | Place an animal in a situation where it has to manipulate some object in order to get an opportunity to nurture its offspring | Place an animal in a situation where it has to model its behaviour on another animal in order to get an opportunity to nurture its offspring |

| PLAY | Controlling and modifying one's behaviour in order to engage in rough-and-tumble play | Ability to modify one's bodily movements in order to get an opportunity to engage in rough-and-tumble play | Ability to modify one's route in order to get an opportunity to engage in rough-and-tumble play | Ability to manipulate objects in order to get an opportunity to engage in rough-and-tumble play | Ability to model one's behaviour on others in order to get an opportunity to engage in rough-and-tumble play |

| General experimental strategy for identifying the occurrence of PLAY | Would the experiment be ethical? Yes. | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its bodily movements in order to get an opportunity to engage in rough-and-tumble play | Place an animal in a situation where it has to modify its route in order to get an opportunity to engage in rough-and-tumble play | Place an animal in a situation where it has to manipulate some object in order to get an opportunity to engage in rough-and-tumble play | Place an animal in a situation where it has to model its behaviour on another animal in order to get an opportunity to engage in rough-and-tumble play |

It should be stressed that all of the above experimental identifications of basic emotions are tentative, and subject to the identification of a dedicated neurological system in the animal's brain (see Conclusion E. 22).

Experiments designed to verify the occurrence of emotions and/or feelings in animals run the risk of being unethical. As Allen (2003) remarks in his discussion of nociception (roughly, the sensory detection of injurious stimuli by an animal's nervous system), "[t]here is a need for serious comparative work in this area, but there are, of course, questions about the ethical propriety of doing more of this kind of work, precisely because it might cause morally objectionabale pain" (2003, p. 19).

The reader will have noticed that I have described four of my seven proposed strategies for experimentally identifying basic emotions in animals as unethical, if carried out. It is not often that a researcher counsels against an experiment he/she has proposed, but animals will try to avoid being made to feel afraid, angry, lonely or worried about their offspring. In other words, to induce these states in animals is to do them emotional harm. According to Panksepp, most animals "readily learn to turn off" electrical stimulation of the brain which artificially induces affective attack, or RAGE, so and concludes that "most animals do have unpleasant affective experiences during such stimulation" (1998, p. 194). However, even if it turns out that the animal is incapable of feeling pain at a conscious level, I believe such conduct to be wrong, for reasons I shall elaborate in chapter five.

It would of course be easy to limit the harm done to experimental animals. For instance, one could design non-invasive experimental techniques to identify anger, such as the following:

Put the animal in a box. Place another animal (actually a lifelike toy) inside its territory and give the animal a chance to attack the toy, but only as long as it moves in a specific way (e.g. run at a certain speed in a specific direction). If it fails to do so, a clear plastic partition comes down and separates the animal from the intruder, which it can still see occupying its territory.

It might be argued that because the above experiment involves no physical cruelty, it is morally justifiable. But in fact, the experimental animal would still be subjected to the physical and emotional stress of having its territory invaded. For this reason, I suggest that research would be better directed at identifying the three emotion systems in animals (seeking, lust and play) where ethical research can be performed.

In play experiments, the animal would have to learn a strategy for obtaining access to its playmates. For instance, the animal could be placed on the other side of a clear plastic partition, giving it a full view of them while they were engaged in play. In order to access its playmates, the animal might have to learn to perform some complicated manoeuvre such as pressing a lever in a particular way (operant conditioning), or successfully navigating a maze (navigational agency), or using some object as a tool to open the partition (tool use), or letting itself be guided to the other side by a video featuring another animal (social learning).

In experiments for identifying sexual desire, the animal would have to perform similar learning feats in order to gain the opportunity to mate with a suitable partner.

Finally, in experiments for identifying seeking (anticipatory eagerness), the animal would have to perform learning tasks in order to maintain a neural state of expectant arousal.