Contents

Remote Access Over the Internet

Connecting Networks Over the Internet

2.2 Tunneling Protocols and the Basic Tunneling Requirements

Phase 1: PPP Link Establishment

Phase 4: Invoking Network Layer Protocol(s)

Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP)

Layer Two Tunneling Protocol (L2TP)

Advantages

of L2TP/IPSec over PPTP

Advantages of PPTP over L2TP/IPSec

Symmetric

vs. Asymmetric Encryption (Private Key vs. Public Key)

Extensible

Authentication Protocol (EAP)

Transport

Level Security (EAP-TLS)

Negotiated

Security Association

Encapsulating

Security Payload

Accounting, Auditing,

and Alarming

Introduction

A

virtual private network (VPN) is the extension of a private network that

encompasses links across shared or public networks like the Internet. A VPN

enables you to send data between two computers across a shared or public

internetwork in a manner that emulates the properties of a point-to-point

private link. The act of configuring and creating a virtual private network is

known as virtual private networking.

To emulate a

point-to-point link, data is encapsulated, or wrapped, with a header that

provides routing information allowing it to traverse the shared or public

transit internetwork to reach its endpoint. To emulate a private link, the data

being sent is encrypted for confidentiality. Packets that are intercepted on the

shared or public network are indecipherable without the encryption keys. The

portion of the connection in which the private data is encapsulated is known as

the tunnel. The portion of the connection in which the private data is encrypted

is known as the virtual private

network (VPN) connection.

Figure 1:

Virtual private network connection

VPN

connections allow users working at home or on the road to connect in a secure

fashion to a remote corporate server using the routing infrastructure provided

by a public internetwork (such as the Internet). From the user’s perspective,

the VPN connection is a point-to-point connection between the user’s computer

and a corporate server. The nature of the intermediate internetwork is

irrelevant to the user because it appears as if the data is being sent over a

dedicated private link.

VPN technology

also allows a corporation to connect to branch offices or to other companies

over a public internetwork (such as the Internet), while maintaining secure

communications. The VPN connection across the Internet logically operates as a

wide area network (WAN) link between the sites.

In both of

these cases, the secure connection across the internetwork appears to the user

as a private network communication—despite the fact that this communication

occurs over a public internetwork—hence the name virtual

private network.

VPN technology

is designed to address issues surrounding the current business trend toward

increased telecommuting and widely distributed global operations, where workers

must be able to connect to central resources and must be able to communicate

with each other.

To provide

employees with the ability to connect to corporate computing resources,

regardless of their location, a corporation must deploy a scalable remote access

solution. Typically, corporations choose either an MIS department solution,

where an internal information systems department is charged with buying,

installing, and maintaining corporate modem pools and a private network

infrastructure; or they choose a value-added network (VAN) solution, where they

pay an outsourced company to buy, install, and maintain modem pools and a

telecommunication infrastructure.

Neither of these solutions provides the necessary scalability, in terms of cost, flexible administration, and demand for connections. Therefore, it makes sense to replace the modem pools and private network infrastructure with a less expensive solution based on Internet technology so that the business can focus on its core competencies. With an Internet solution, a few Internet connections through Internet service providers (ISPs) and VPN server computers can serve the remote networking needs of hundreds or thousands of remote clients and branch offices.

The

next few subsections describe the more common VPN configurations in more detail.

VPNs

provide remote access to corporate resources over the public Internet, while

maintaining privacy of information. Figure 2 shows a VPN connection used to

connect a remote user to a corporate intranet.

Figure

2: Using a VPN connection to connect a remote client to a private intranet

Rather

than making a long distance (or 1-800) call to a corporate or outsourced network

access server (NAS), the user calls a local ISP. Using the connection to the

local ISP, the VPN software creates a virtual private network between the

dial-up user and the corporate VPN server across the Internet.

There

are two methods for using VPNs to connect local area networks at remote sites:

·

Using

dedicated lines to connect a branch office to a corporate LAN.

Rather than using an expensive long-haul dedicated circuit between the branch

office and the corporate hub, both the branch office and the corporate hub

routers can use a local dedicated circuit and local ISP to connect to the

Internet. The VPN software uses the local ISP connections and the Internet to

create a virtual private network between the branch office router and corporate

hub router.

·

Using

a dial-up line to connect a branch office to a corporate LAN.

Rather than having a router at the branch office make a long distance (or 1-800)

call to a corporate or outsourced NAS, the router at the branch office can call

the local ISP. The VPN software uses the connection to the local ISP to create a

VPN between the branch office router and the corporate hub router across the

Internet.

Figure

3: Using a VPN connection to connect two remote sites

In

both cases, the facilities that connect the branch office and corporate offices

to the Internet are local. The corporate hub router that acts as a VPN server

must be connected to a local ISP with a dedicated line. This VPN server must be

listening 24 hours a day for incoming VPN traffic.

In

some corporate internetworks, the departmental data is so sensitive that the

department’s LAN is physically disconnected from the rest of the corporate

internetwork. Although this protects the department’s confidential

information, it creates information accessibility problems for those users not

physically connected to the separate LAN.

Figure

4: Using a VPN connection to connect to a secured or hidden network

VPNs allow the department’s LAN to be physically connected to the corporate internetwork but separated by a VPN server. The VPN server is not acting as a router between the corporate internetwork and the department LAN. A router would connect the two networks, allowing everyone access to the sensitive LAN. By using a VPN, the network administrator can ensure that only those users on the corporate internetwork who have appropriate credentials (based on a need-to-know policy within the company) can establish a VPN with the VPN server and gain access to the protected resources of the department. Additionally, all communication across the VPN can be encrypted for data confidentiality. Those users who do not have the proper credentials cannot view the department LAN.

Typically,

when deploying a remote networking solution, an enterprise needs to facilitate

controlled access to corporate resources and information. The solution must

allow roaming or remote clients to connect to LAN resources, and the solution

must allow remote offices to connect to each other to share resources and

information (router-to-router connections). In addition, the solution must

ensure the privacy and integrity of data as it traverses the Internet. The same

concerns apply in the case of sensitive data traversing a corporate internetwork.

Therefore,

a VPN solution should provide at least all of the following:

·

User

Authentication. The solution must

verify the VPN client’s identity and restrict VPN access to authorized users

only. It must also provide audit and accounting records to show who accessed

what information and when.

·

Address

Management. The solution must assign

a VPN client’s address on the intranet and ensure that private addresses are

kept private.

·

Data

Encryption. Data carried on the

public network must be rendered unreadable to unauthorized clients on the

network.

·

Key

Management. The solution must

generate and refresh encryption keys for the client and the server.

·

Multiprotocol

Support. The solution must handle

common protocols used in the public network. These include IP, Internetwork

Packet Exchange (IPX), and so on.

An Internet VPN solution based on the Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP) or Layer Two Tunneling Protocol (L2TP) meets all of these basic requirements and takes advantage of the broad availability of the Internet. Other solutions, including Internet Protocol Security (IPSec), meet only some of these requirements, but remain useful for specific situations.

VPNs promise two main advantages over competing approaches -- cost savings, and scalability (that is really just a different form of cost savings).

One way a VPN lowers costs is by eliminating the need for expensive long-distance leased lines. With VPNs, an organization needs only a relatively short dedicated connection to the service provider. This connection could be a local leased line (much less expensive than a long-distance one), or it could be a local broadband connection such as DSL service.

Another way VPNs reduce costs is by lessening the need for long-distance telephone charges for remote access. Recall that to provide remote access service, VPN clients need only call into the nearest service provider's access point. In some cases this may require a long distance call, but in many cases a local call will suffice.

A third, more subtle way that VPNs may lower costs is through offloading of the support burden. With VPNs, the service provider rather than the organization must support dial-up access, for example. Service providers can in theory charge much less for their support than it costs a company internally because the public provider's cost is shared amongst potentially thousands of customers.

The cost to an organization of traditional leased lines may be reasonable at first but can increase exponentially as the organization grows. A company with two branch offices, for example, can deploy just one dedicated line to connect the two locations. If a third branch office needs to come online, just two additional lines will be required to directly connect that location to the other two.

However, as an organization grows and more companies must be added to the network, the number of leased lines required increases dramatically. Four branch offices require six lines for full connectivity, five offices require ten lines, and so on. Mathematicans call this phenomenon a "combinatorial explosion," and in a traditional WAN this explosion limits the flexibility for growth. VPNs that utilize the Internet avoid this problem by simply tapping into the geographically-distributed access already available.

Compared to leased lines, Internet-based VPNs offer greater global reach, given that Internet access points are accessible in many places where dedicated lines are not available.

With the hype that has surrounded VPNs historically, the potential pitfalls or "weak spots" in the VPN model can be easy to forget. These four concerns with VPN solutions are often raised.

1.

VPNs require an in-depth understanding of public network security issues and

taking proper precautions in VPN deployment.

2. The availability and performance of an organization's wide-area VPN (over the

Internet in particular) depends on factors largely outside of their control.

3. VPN technologies from different vendors may not work well together due to

immature standards.

4. VPNs need to accomodate protocols other than IP and existing

("legacy") internal network technology.

TUNNELING

Basics

Tunneling

is a method of using an internetwork infrastructure to transfer data for one

network over another network. The data to be transferred (or payload)

can be the frames (or packets) of another protocol. Instead of sending a frame

as it is produced by the originating node, the tunneling protocol encapsulates

the frame in an additional header. The additional header provides routing

information so that the encapsulated payload can traverse the intermediate

internetwork.

The

encapsulated packets are then routed between tunnel endpoints over the

internetwork. The logical path through which the encapsulated packets travel

through the internetwork is called a tunnel.

Once the encapsulated frames reach their destination on the internetwork, the

frame is decapsulated and forwarded to its final destination. Tunneling includes

this entire process (encapsulation, transmission, and decapsulation of packets).

Figure

5: Tunneling

The

transit internetwork can be any internetwork—the Internet is a public

internetwork and is the most widely known real world example. There are many

examples of tunnels that are carried over corporate internetworks. And while the

Internet provides one of the most pervasive and cost-effective internetworks,

references to the Internet in this paper can be replaced by any other public or

private internetwork that acts as a transit internetwork.

Tunneling

technologies have been in existence for some time. Some examples of mature

technologies include:

·

SNA

tunneling over IP internetworks. When

System Network Architecture (SNA) traffic is sent across a corporate IP

internetwork, the SNA frame is encapsulated in a UDP and IP header.

·

IPX

tunneling for Novell NetWare over IP internetworks.

When

an IPX packet is sent to a NetWare server or IPX router, the server or the

router wraps the IPX packet in a UDP and IP header, and then sends it across an

IP internetwork. The destination IP-to-IPX router removes the UDP and IP header

and forwards the packet to the IPX destination.

New

tunneling technologies have been introduced in recent years. These newer

technologies—which are the primary focus of this paper—include:

·

Point-to-Point

Tunneling Protocol (PPTP).

PPTP allows IP, IPX, or NetBEUI traffic to be encrypted, and then encapsulated

in an IP header to be sent across a corporate IP internetwork or a public IP

internetwork such as the Internet.

·

Layer

Two Tunneling Protocol (L2TP). L2TP

allows IP, IPX, or NetBEUI traffic to be encrypted, and then sent over any

medium that supports point-to-point datagram delivery, such as IP, X.25, Frame

Relay, or ATM.

· IPSec tunnel mode. IPSec tunnel mode allows IP packets to be encrypted, and then encapsulated in an IP header to be sent across a corporate IP internetwork or a public IP internetwork such as the Internet.

For

Layer 2 tunneling technologies, such as PPTP and L2TP, a tunnel is similar to a

session; both of the tunnel endpoints must agree to the tunnel and must

negotiate configuration variables, such as address assignment or encryption or

compression parameters. In most cases, data transferred across the tunnel is

sent using a datagram-based protocol. A tunnel maintenance protocol is used as

the mechanism to manage the tunnel.

Layer

3 tunneling technologies generally assume that all of the configuration issues

are preconfigured, often by manual processes. For these protocols, there may be

no tunnel maintenance phase. For Layer 2 protocols (PPTP and L2TP), however, a

tunnel must be created, maintained, and then terminated.

Once the tunnel is established, tunneled data can be sent. The tunnel client or server uses a tunnel data transfer protocol to prepare the data for transfer. For example, when the tunnel client sends a payload to the tunnel server, the tunnel client first appends a tunnel data transfer protocol header to the payload. The client then sends the resulting encapsulated payload across the internetwork, which routes it to the tunnel server. The tunnel server accepts the packets, removes the tunnel data transfer protocol header, and forwards the payload to the target network. Information sent between the tunnel server and the tunnel client behaves similarly.

Because

they are based on the well-defined PPP protocol, Layer 2 protocols (such as PPTP

and L2TP) inherit a suite of useful features. These features, and their Layer 3

counterparts address the basic VPN requirements, as outlined below.

·

User

Authentication. Layer 2 tunneling

protocols inherit the user authentication schemes of PPP, including the EAP

methods discussed below. Many Layer 3 tunneling schemes assume that the

endpoints were well known (and authenticated) before the tunnel was established.

An exception to this is IPSec Internet Key Exchange (IKE) negotiation, which

provides mutual authentication of the tunnel endpoints. Most IPSec

implementations including Windows 2000 support computer-based certificates only,

rather than user certificates. As a result, any user with access to one of the

endpoint computers can use the tunnel. This potential security weakness can be

eliminated when IPSec is paired with a Layer 2 protocol such as L2TP.

Token

card support. Using the Extensible Authentication Protocol (EAP), Layer 2

tunneling protocols can support a wide variety of authentication methods,

including one-time passwords, cryptographic calculators, and smart cards. Layer

3 tunneling protocols can use similar methods; for example, IPSec defines public

key certificate authentication in its IKE negotiation.

·

Dynamic

address assignment.

Layer 2 tunneling supports dynamic

assignment of client addresses based on the Network Control Protocol (NCP)

negotiation mechanism. Generally, Layer 3 tunneling schemes assume that an

address has already been assigned prior to initiation of the tunnel. Schemes for

assignment of addresses in IPSec tunnel mode are currently under development and

are not yet available.

·

Data

compression. Layer 2 tunneling

protocols support PPP-based compression schemes. For example, the Microsoft

implementations of both PPTP and L2TP use Microsoft Point-to-Point Compression (MPPC).

The IETF is investigating similar mechanisms (such as IP Compression) for the

Layer 3 tunneling protocols.

·

Data

encryption. Layer 2 tunneling

protocols support PPP-based data encryption mechanisms. The Microsoft

implementation of PPTP supports optional use of Microsoft Point-to-Point

Encryption (MPPE), based on the RSA/RC4 algorithm. Layer 3 tunneling protocols

can use similar methods; for example, IPSec defines several optional data

encryption methods, which are negotiated during the IKE exchange. The Microsoft

implementation of the L2TP protocol uses IPSec encryption to protect the data

stream from the VPN client to the VPN server.

·

Key

Management. MPPE, a Layer 2

encryption mechanism, relies on the initial key generated during user

authentication, and then refreshes it periodically. IPSec explicitly negotiates

a common key during the IKE exchange, and also refreshes it periodically.

· Multiprotocol support. Layer 2 tunneling supports multiple payload protocols, which makes it easy for tunneling clients to access their corporate networks using IP, IPX, NetBEUI, and so on. In contrast, Layer 3 tunneling protocols, such as IPSec tunnel mode, typically support only target networks that use the IP protocol.

Because

the Layer 2 protocols depend heavily on the features originally specified for

PPP, it is worth examining this protocol more closely. PPP was designed to send

data across dial-up or dedicated point-to-point connections. PPP encapsulates

IP, IPX, and NetBEUI packets within PPP frames, and then transmits the

PPP-encapsulated packets across a point-to-point link. PPP is used between a

dial-up client and an NAS.

There are four distinct phases of negotiation in a PPP dial-up session. Each of these four phases must complete successfully before the PPP connection is ready to transfer user data.

PPP uses Link Control Protocol (LCP) to establish, maintain, and end the physical connection. During the initial LCP phase, basic communication options are selected. During the link establishment phase (Phase 1), authentication protocols are selected, but they are not actually implemented until the connection authentication phase (Phase 2). Similarly, during LCP a decision is made as to whether the two peers will negotiate the use of compression and/or encryption. The actual choice of compression and encryption algorithms and other details occurs during Phase 4.

In

the second phase, the client PC presents the user’s credentials to the remote

access server. A secure authentication scheme provides protection against replay

attacks and remote client impersonation. A replay attack occurs when a third party monitors a successful

connection and uses captured packets to play back the remote client’s response

so that it can gain an authenticated connection. Remote client impersonation occurs when a third party takes over an

authenticated connection. The intruder waits until the connection has been

authenticated, and then traps the conversation parameters, disconnects the

authenticated user, and takes control of the authenticated connection.

Most

implementations of PPP provide limited authentication methods, typically

Password Authentication Protocol (PAP), Challenge Handshake Authentication

Protocol (CHAP), and Microsoft Challenge Handshake Authentication Protocol

(MS-CHAP).

·

Password

Authentication Protocol (PAP).

PAP is a simple, clear-text authentication scheme. The NAS requests the user

name and password, and PAP returns them in clear text (unencrypted). Obviously,

this authentication scheme is not secure because a third party could capture the

user’s name and password and use it to get subsequent access to the NAS and

all of the resources provided by the NAS. PAP provides no protection against

replay attacks or remote client impersonation once the user’s password is

compromised.

·

Challenge-Handshake

Authentication Protocol (CHAP).

CHAP is an encrypted authentication mechanism that avoids transmission of the

actual password on the connection. The NAS sends a challenge, which consists of

a session ID and an arbitrary challenge string, to the remote client. The

remote client must use the MD5 one-way hashing algorithm to return the user name

and an encryption of the challenge, session ID, and the client’s password. The

user name is sent unhashed.

CHAP

is an improvement over PAP because the clear-text password is not sent over the

link. Instead, the password is used to create an encrypted hash from the

original challenge. The server knows the client’s clear-text password and can,

therefore, replicate the operation and compare the result to the password sent

in the client’s response. CHAP protects against replay attacks by using an

arbitrary challenge string for each authentication attempt. CHAP protects

against remote client impersonation by unpredictably sending repeated challenges

to the remote client throughout the duration of the connection.

·

Microsoft

Challenge-Handshake Authentication Protocol (MS-CHAP).

MS-CHAP is an encrypted authentication mechanism very similar to CHAP. As in

CHAP, the NAS sends a challenge, which consists of a session ID and an arbitrary

challenge string, to the remote client. The remote client must return the user

name and an encrypted form of the challenge string, the session ID, and the

MD4-hashed password. This design, which uses a hash of the MD4 hash of the

password, provides an additional level of security because it allows the server

to store hashed passwords instead of clear-text passwords. MS-CHAP also provides

additional error codes, including a password expired code, and additional

encrypted client-server messages that permit users to change their passwords. In

MS-CHAP, both the access client and the NAS independently generate an initial

key for subsequent data encryption by MPPE. Therefore, MS-CHAP authentication is

required to enable MPPE-based data encryption.

·

MS-CHAP

version 2 (MS-CHAP v2).

MS-CHAP v2 is an updated encrypted authentication mechanism that provides

stronger security for the exchange of user name and password credentials and

determination of encryption keys. With MS-CHAP v2, the NAS sends a challenge to

the access client that consists of a session identifier and an arbitrary

challenge string. The remote access client sends a response that contains the

user name, an arbitrary peer challenge string, and an encrypted form of the

received challenge string, the peer challenge string, the session identifier,

and the user's password. The NAS checks the response from the client and sends

back a response containing an indication of the success or failure of the

connection attempt and an authenticated response based on the sent challenge

string, the peer challenge string, the encrypted response of the client, and the

user's password. The remote access client verifies the authentication response

and, if correct, uses the connection. If the authentication response is not

correct, the remote access client terminates the connection.

Using

this process, MS-CHAP v2 provides mutual authentication¾the

NAS verifies that the access client has knowledge of the user's password and the

access client verifies that the NAS has knowledge of the user's password.

MS-CHAP v2 also determines two encryption keys, one for data sent and one for

data received.

During

phase 2 of PPP link configuration, the NAS collects the authentication data, and

then validates the data against its own user database or a central

authentication database server, such as one maintained by a Windows domain

controller, or the authentication data is sent to a Remote Authentication

Dial-in User Service (RADIUS) server.

The

Microsoft implementation of PPP includes an optional callback control phase.

This phase uses the Callback Control Protocol (CBCP) immediately after the

authentication phase. If configured for callback, both the remote client and NAS

disconnect after authentication. The NAS then calls the remote client back at a

specified phone number. This provides an additional level of security to dial-up

networking. The NAS allows connections from remote clients physically residing

at specific phone numbers only.

Once

the previous phases have been completed, PPP invokes the various network control

protocols (NCPs) that were selected during the link establishment phase (Phase

1) to configure protocols used by the remote client. For example, during this

phase the IP control protocol (IPCP) can assign a dynamic address to the dial-in

user. In the Microsoft implementation of PPP, the compression control protocol

is used to negotiate both data compression (using MPPC) and data encryption

(using MPPE) for because both are implemented in the same routine.

Once

the four phases of negotiation have been completed, PPP begins to forward data

to and from the two peers. Each transmitted data packet is wrapped in a

PPP header which is removed by the receiving system. If data compression was

selected in phase 1 and negotiated in phase 4, data is compressed before

transmission. If data encryption is selected and negotiated, data is encrypted

before transmission.

PPTP

is a Layer 2 protocol that encapsulates PPP frames in IP datagrams for

transmission over an IP internetwork, such as the Internet. PPTP can be used for

remote access and router-to-router VPN connections. PPTP is documented in RFC

2637.

The

Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol (PPTP) uses a TCP connection for tunnel

maintenance and a modified version of Generic Routing Encapsulation (GRE) to

encapsulate PPP frames for tunneled data. The payloads of the encapsulated PPP

frames can be encrypted and/or compressed. Figure 6 shows the structure of a

PPTP packet containing user data.

Figure 6. Structure of a PPTP packet containing user data

L2TP

is a combination of PPTP and Layer 2 Forwarding (L2F), a technology proposed by

Cisco Systems, Inc. L2TP represents the best features of PPTP and L2F. L2TP

encapsulates PPP frames to be sent over IP, X.25, Frame Relay, or Asynchronous

Transfer Mode (ATM) networks. When configured to use IP as its datagram

transport, L2TP can be used as a tunneling protocol over the Internet. L2TP is

documented in RFC 2661.

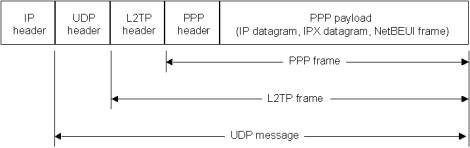

L2TP

over IP internetworks uses UDP and a series of L2TP messages for tunnel

maintenance. L2TP also uses UDP to send L2TP-encapsulated PPP frames as the

tunneled data. The payloads of encapsulated PPP frames can be encrypted and/or

compressed. Figure 7 shows the structure of an L2TP packet containing user data.

Figure

7. Structure of an L2TP packet containing user data

In

Windows 2000, IPSec Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP) is used to encrypt the

L2TP packet. This is known as L2TP/IPSec. The result after applying ESP is shown

in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Encryption of an L2TP packet with IPSec ESP

Both

PPTP and L2TP/IPSec use PPP to provide an initial envelope for the data, and

then append additional headers for transport through the internetwork. However,

there are the following differences:

·

With PPTP, data encryption begins

after the PPP connection process (and, therefore, PPP authentication) is

completed. With L2TP/IPSec, data encryption begins before the PPP connection

process by negotiating an IPSec security association.

·

PPTP connections use MPPE, a

stream cipher that is based on the Rivest-Shamir-Aldeman (RSA) RC-4 encryption

algorithm and uses 40, 56, or 128-bit encryption keys. Stream ciphers encrypt

data as a bit stream. L2TP/IPSec connections use the Data Encryption Standard

(DES), which is a block cipher that uses either a 56-bit key for DES or three

56-bit keys for 3-DES. Block ciphers encrypt data in discrete blocks (64-bit

blocks, in the case of DES).

· PPTP connections require only user-level authentication through a PPP-based authentication protocol. L2TP/IPSec connections require the same user-level authentication and, in addition, computer-level authentication using computer certificates.

The

following are the advantages of using L2TP/IPSec over PPTP in Windows 2000:

·

IPSec provides per packet data

authentication (proof that the data was sent by the authorized user), data

integrity (proof that the data was not modified in transit), replay protection

(prevention from resending a stream of captured packets), and data

confidentiality (prevention from interpreting captured packets without the

encryption key). By contrast, PPTP provides only per-packet data

confidentiality.

·

L2TP/IPSec connections provide

stronger authentication by requiring both computer-level authentication through

certificates and user-level authentication through a PPP authentication

protocol.

· PPP packets exchanged during user-level authentication are never sent in an unencrypted form because the PPP connection process for L2TP/IPSec occurs after the IPSec security associations (SAs) are established. If intercepted, the PPP authentication exchange for some types of PPP authentication protocols can be used to perform offline dictionary attacks and determine user passwords. By encrypting the PPP authentication exchange, offline dictionary attacks are only possible after the encrypted packets have been successfully decrypted.

The

following are advantages of PPTP over L2TP/IPSec in Windows 2000:

·

PPTP does not require a

certificate infrastructure. L2TP/IPSec requires a certificate infrastructure for

issuing computer certificates to the VPN server computer (or other

authenticating server) and all VPN client computers.

·

PPTP can be used by computers

running Windows XP, Windows 2000, Windows NT version 4.0, Windows Millennium

Edition (ME), Windows 98, and Windows 95 with the Windows Dial-Up Networking 1.3

Performance & Security Update. L2TP/IPSec can only be used with Windows XP

and Windows 2000 VPN clients. Only these clients support the L2TP

protocol, IPSec, and the use of certificates.

· PPTP clients and server can be placed behind a network address translator (NAT) if the NAT has the appropriate editors for PPTP traffic. L2TP/IPSec-based VPN clients or servers cannot be placed behind a NATunless both support IPSec NAT Traversal (NAT-T). IPSec NAT-T is supported by Windows Server 2003, Microsoft L2TP/IPSec VPN Client, and for VPN clients with L2TP/IPSec NAT-T Update for Windows XP and Windows 2000.

IPSec

is a Layer 3 protocol standard that supports the secured transfer of information

across an IP internetwork. IPSec is more fully described in the Advanced

Security section below. However,

one aspect of IPSec should be discussed in the context of tunneling protocols.

In addition to its definition of encryption mechanisms for IP traffic, IPSec

defines the packet format for an IP over IP tunnel mode, generally referred to

as IPSec tunnel mode. An IPSec tunnel

consists of a tunnel client and a tunnel server, which are both configured to

use IPSec tunneling and a negotiated encryption mechanism.

IPSec

tunnel mode uses the negotiated security method (if any) to encapsulate and

encrypt entire IP packets for secure transfer across a private or public IP

internetwork. The encrypted payload is then encapsulated again with a plain-text

IP header and sent on the internetwork for delivery to the tunnel server. Upon

receipt of this datagram, the tunnel server processes and discards the

plain-text IP header, and then decrypts its

contents to retrieve the original payload IP packet. The payload IP packet is

then processed normally and routed to its destination on the target network.

IPSec

tunnel mode has the following features and limitations:

·

It supports IP traffic only.

·

It functions at the bottom of the

IP stack; therefore, applications and higher-level protocols inherit its

behavior.

· It is controlled by a security policy—a set of filter-matching rules. This security policy establishes the encryption and tunneling mechanisms available, in order of preference, and the authentication methods available, also in order of preference. As soon as there is traffic, the two computers perform mutual authentication, and then negotiate the encryption methods to be used. Thereafter, all traffic is encrypted using the negotiated encryption mechanism, and then wrapped in a tunnel header.

Tunnels

can be created in various ways.

·

Voluntary

tunnels: A user or client computer

can issue a VPN request to configure and create a voluntary tunnel. In this

case, the user’s computer is a tunnel endpoint and acts as the tunnel client.

·

Compulsory

tunnels: A VPN-capable dial-up access

server configures and creates a compulsory tunnel. With a compulsory tunnel, the

user’s computer is not a tunnel endpoint. Another device, the dial-up access

server, between the user’s computer and the tunnel server is the tunnel

endpoint and acts as the tunnel client.

To date, voluntary tunnels are proving to be the more popular type of tunnel. The following sections describe each of these tunnel types in greater detail.

Voluntary

tunneling occurs when a workstation or routing server uses tunneling client

software to create a virtual connection to the target tunnel server. To

accomplish this, the appropriate tunneling protocol must be installed on the

client computer. For the protocols discussed in this paper, voluntary tunnels

require an IP connection (either LAN or dial-up).

In

a dial-up situation, the client must establish a dial-up connection

to the internetwork before the client can set up a tunnel. This is the

most common case. The best example of this is the dial-up Internet user, who

must dial an ISP and obtain an Internet connection before a tunnel over the

Internet can be created.

For

a LAN-attached computer, the client already has a connection to the internetwork

that can provide routing of encapsulated payloads to the chosen LAN tunnel

server. This would be the case for a client on a corporate LAN that initiates a

tunnel to reach a private or hidden subnet on that LAN (such as the Human

Resources network discussed previously).

It is a common misconception that VPN connections require a dial-up connection. They require only IP connectivity between the VPN client and VPN server. Some clients (such as home computers) use dial-up connections to the Internet to establish IP transport. This is a preliminary step in preparation for creating a tunnel and is not part of the tunnel protocol itself.

A

number of vendors that sell dial-up access servers have implemented the ability

to create a tunnel on behalf of a dial-up client. The computer or network device

providing the tunnel for the client computer is variously known as a Front End

Processor (FEP) in PPTP, an L2TP Access Concentrator (LAC) in L2TP, or an IP

Security Gateway in IPSec. For the purposes of this white paper, the term FEP is

used to describe this functionality, regardless of the tunneling protocol. To

carry out its function, the FEP must have the appropriate tunneling protocol

installed and must be capable of establishing the tunnel when the client

computer connects.

In

the Internet example, the client computer places a dial-up call to a

tunneling-enabled NAS at the ISP. For example, a corporation may have contracted

with an ISP to deploy a nationwide set of FEPs. These FEPs can establish tunnels

across the Internet to a tunnel server connected to the corporation’s private

network, thus consolidating calls from geographically diverse locations into a

single Internet connection at the corporate network.

This

configuration is known as compulsory tunneling because the client is compelled

to use the tunnel created by the FEP. Once the initial connection is made, all

network traffic to and from the client is automatically sent through the tunnel.

With compulsory tunneling, the client computer makes a single PPP connection.

When a client dials into the NAS, a tunnel is created and all traffic is

automatically routed through the tunnel. An FEP can be configured to tunnel all

dial-up clients to a specific tunnel server. The FEP could also tunnel

individual clients, based on the user name or destination.

Unlike

the separate tunnels created for each voluntary client, a tunnel between the FEP

and the tunnel server can be shared by multiple dial-up clients. When a second

client dials into the access server (FEP) to reach a destination for which a

tunnel already exists, there is no need to create a new instance of the tunnel

between the FEP and tunnel server. Instead, the data traffic for the new client

is carried over the existing tunnel. Since there can be multiple clients in a

single tunnel, the tunnel is not terminated until the last user of the tunnel

disconnects.

Advanced

SECURITY

Features

Because

the Internet facilitates the creation of VPNs from anywhere, networks need

strong security features to prevent unwelcome access to private networks and to

protect private data as it traverses the public network. User authentication and

data encryption have already been discussed. This section provides a brief look

ahead to the stronger authentication and encryption capabilities that are

available with EAP and IPSec.

Symmetric,

or private-key, encryption (also known as conventional encryption) is based on a

secret key that is shared by both communicating parties. The sending party uses

the secret key as part of the mathematical operation to encrypt (or encipher)

plain text to cipher text. The receiving party uses the same secret key to

decrypt (or decipher) the cipher text to plain text. Examples of symmetric

encryption schemes are the RSA RC4 algorithm (which provides the basis for

Microsoft Point-to-Point Encryption (MPPE), Data Encryption Standard (DES), the

International Data Encryption Algorithm (IDEA), and the Skipjack encryption

technology proposed by the United States government (and implemented in the

Clipper chip).

Asymmetric,

or public-key, encryption uses two different keys for each user: one is a

private key known only to this one user; the other is a corresponding public

key, which is accessible to anyone. The private and public keys are

mathematically related by the encryption algorithm. One key is used for

encryption and the other for decryption, depending on the nature of the

communication service being implemented.

In

addition, public key encryption technologies allow digital signatures to be

placed on messages. A digital signature uses the sender’s private key to

encrypt some portion of the message. When the message is received, the receiver

uses the sender’s public key to decipher the digital signature to verify the

sender’s identity.

With

symmetric encryption, both sender and receiver have a shared secret key. The

distribution of the secret key must occur (with adequate protection) prior to

any encrypted communication. However, with asymmetric encryption, the sender

uses a private key to encrypt or digitally sign messages, while the receiver

uses a public key to decipher these messages. The public key can be freely

distributed to anyone who needs to receive the encrypted or digitally

signed messages. The sender needs to carefully protect the private key only.

To

secure the integrity of the public key, the public key is published with a certificate.

A certificate (or public key

certificate) is a data structure that is digitally signed by a certification

authority (CA)—an authority that users of the certificate can trust. The

certificate contains a series of values, such as the certificate name and usage,

information identifying the owner of the public key, the public key itself, an

expiration date, and the name of the certificate authority. The CA uses its

private key to sign the certificate. If the receiver knows the public key of the

certificate authority, the receiver can verify that the certificate is indeed

from the trusted CA and, therefore, contains reliable information and a valid

public key. Certificates can be distributed electronically (through Web access

or email), on smart cards, or on floppy disks.

In summary, public key certificates provide a convenient, reliable method for verifying the identity of a sender. IPSec can optionally use this method for end-to-end authentication. Remote access servers can use public key certificates for user authentication, as described in the section "Transport Level Security (EAP-TLS)."

As

stated previously, most implementations of PPP provide very limited

authentication methods. EAP is an IETF standard extension to PPP that allows for

arbitrary authentication mechanisms for the validation of a PPP connection. EAP

was designed to allow the dynamic addition of authentication plug-in modules at

both the client and server ends of a connection. This allows vendors to supply a

new authentication scheme at any time. EAP provides the highest flexibility in

authentication uniqueness and variation.

EAP is documented in RFC 2284 and is supported in Microsoft Windows 2000.

EAP-TLS

is an IETF standard (RFC 2716) for a strong authentication method based on

public-key certificates. With EAP-TLS, a client presents a user certificate to

the dial-in server, and the server presents a server certificate to the client.

The first provides strong user authentication to the server; the second provides

assurance that the user has reached the server that he or she expected. Both

systems rely on a chain of trusted authorities to verify the validity of the

offered certificate.

The

user’s certificate could be stored on the dial-up client computer or

stored in an external smart card. In either case, the certificate cannot be

accessed without some form of user identification (PIN number or

name-and-password exchange) between the user and the client computer. This

approach meets the something-you-know-plus-something-you-have criteria

recommended by most security experts.

EAP-TLS is the specific EAP method implemented in Microsoft Windows 2000. Like MS-CHAP and MS-CHAP v2, EAP-TLS returns an encryption key to enable subsequent data encryption by MPPE.

IP

Security (IPSec) was designed by the IETF as an end-to-end mechanism for

ensuring data security in IP-based communications. IPSec has been defined in a

series of RFCs, notably RFCs 2401, 2402, and 2406, which define the overall

architecture, an authentication header to verify data integrity, and an

encapsulation security payload for both data integrity and data encryption.

IPSec

defines two functions that ensure confidentiality: data encryption and data

integrity. As defined by the IETF, IPSec uses an authentication header (AH) to

provide source authentication and integrity without encryption, and the

Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP) to provide authentication and integrity

along with encryption. With IPSec, only the sender and recipient know the

security key. If the authentication data is valid, the recipient knows that the

communication came from the sender and that it was not changed in transit.

IPSec can be envisioned as a layer below the TCP/IP stack. This layer is controlled by a security policy on each computer and a negotiated security association between the sender and receiver. The policy consists of a set of filters and associated security behaviors. If a packet’s IP address, protocol, and port number match a filter, the packet is subject to the associated security behavior.

The

first such packet triggers a negotiation of a security association between the

sender and receiver. Internet Key Exchange (IKE) is the standard protocol for

this negotiation. During an IKE negotiation, the two computers agree on

authentication and data-security methods, perform mutual authentication, and

then generate a shared key for subsequent data encryption.

After

the security association has been established, data transmission can proceed for

each computer, applying data security treatment to the packets that it transmits

to the remote receiver. The treatment can simply ensure the integrity of the

transmitted data, or it can encrypt it as well.

Data

integrity and data authentication for IP payloads can be provided by an

authentication header located between the IP header and the transport header.

The authentication header includes authentication data and a sequence number,

which together are used to verify the sender, ensure that the message has not

been modified in transit, and prevent a replay attack.

The

IPSec authentication header provides no data encryption; clear-text messages can

be sent, and the authentication header ensures that they originated from a

specific user and were not modified in transit.

For

both data confidentiality and protection from third-party capture, ESP provides

a mechanism to encrypt the IP payload. ESP also provides data authentication and

data integrity services; therefore, ESP is an alternative to AH

when data confidentiality is required.

In

selecting a VPN technology, it is important to consider administrative issues.

Large networks need to store per-user directory information in a centralized

data store, or directory service,

so that administrators and applications can add to, modify, or query this

information. Each access or tunnel server could maintain its own internal data

base of per-user properties, such as names, passwords, and dial-in permission

attributes. However, because it is administratively prohibitive to maintain

multiple user accounts on multiple servers and keep them simultaneously current,

most administrators set up a master account database at the directory server or

primary domain controller, or on a RADIUS server.

The

Routing and Remote Access service in Windows 2000 Server is designed to work

with per-user information stored locally or on a domain controller or on a

RADIUS server. Using a domain controller simplifies system administration

because dial-up permissions are a subset of the per-user information that the

administrator is already managing in a single database.

The

Routing and Remote Access service is both a dial-up remote access server and VPN

server for PPTP and L2TP connections. Consequently, these Layer 2 VPN solutions

inherit all of the management infrastructure already in place for dial-up

networking.

In

Windows 2000, the Routing and Remote Access service takes advantage of the

new Active Directory, an enterprise-wide, replicated database based on the

Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP). LDAP is an industry-standard

protocol for accessing directory services and was developed as a simpler

alternative to the X.500 DAP protocol. LDAP is extensible, vendor-independent,

and standards-based. This integration with the Active Directory allows an

administrator to assign a variety of connection properties for dial-up or VPN

sessions to individual users or groups. These properties can define per-user

filters, required authentication or encryption methods, time-of-day limitations,

and so on.

Redundancy

and load balancing is accomplished using round-robin DNS to split requests among

a number of VPN tunnel servers that share a common security perimeter. A

security perimeter has one external DNS name—for example, microsoft.com—but

several IP addresses, and loads are randomly distributed across all of the IP

addresses. All servers can authenticate access requests against a shared

database, such as a Windows domain controller. Windows domain databases are

replicated between domain controllers.

The

Remote Authentication Dial-in User Service (RADIUS) protocol is a popular method

for managing remote user authentication and authorization. RADIUS is a

lightweight, UDP-based protocol. RADIUS servers can be located anywhere on the

Internet and provide authentication (including PPP PAP, CHAP, MS-CHAP,

MS-CHAP v2, and EAP) and authorization for access servers such as NASes

and VPN servers.

In addition, RADIUS servers can provide a proxy service to forward authentication requests to distant RADIUS servers. For example, many ISPs have joined consortia to allow roaming subscribers to use local services from the nearest ISP for dial-up access to the Internet. These roaming alliances take advantage of the RADIUS proxy service. If an ISP recognizes a user name as being a subscriber to a remote network, the ISP uses a RADIUS proxy to forward the access request to the appropriate network.

To

properly administer a VPN system, network administrators should be able to track

who uses the system, how many connections are made, unusual activity, error

conditions, and situations that may indicate equipment failure. This information

can be used for billing, auditing, and alarm or error-notification purposes.

For

example, an administrator may need to know who connected to the system and for

how long in order to construct billing data. Unusual activity may indicate a

misuse of the system or inadequate system resources. Real-time monitoring of

equipment (for example, unusually high activity on one modem and inactivity on

another) may generate alerts to notify the administrator of a modem failure. The

tunnel server should provide all of this information, and the system should

provide event logs, reports, and a data storage facility to handle the data

appropriately.

The RADIUS protocol defines a suite of call-accounting requests that are independent from the authentication requests discussed above. These messages from the NAS to the RADIUS server request the latter to generate accounting records at the start of a call, the end of a call, and at predetermined intervals during a call. The Routing and Remote Access service can be configured to generate these RADIUS accounting requests separately from connection requests (which could go to the domain controller or to a RADIUS server). This allows an administrator to configure an accounting RADIUS server, whether RADIUS is used for authentication or not. An accounting server can then collect records for every VPN connection for later analysis. A number of third-parties have already written billing and audit packages that read these RADIUS accounting records and produce various useful reports.

VPNs

allow users or corporations to connect to remote servers, branch offices, or to

other companies over a public internetwork, while maintaining secure

communications. In all of these cases, the secure connection appears to the user

as a private network

communication—despite the fact that this communication occurs over a public

internetwork. VPN technology is designed to address issues surrounding the

current business trend toward increased telecommuting and widely distributed

global operations, where workers must be able to connect to central resources

and communicate with each other.

This paper provides an overview of VPN and describes the basic requirements of useful VPN technologies: user authentication, address management, data encryption, key management, and multiprotocol support. It discusses how Layer 2 protocols, specifically PPTP and L2TP, meet these requirements.