The Home Page · The Integral Worm · My Resume · My Show Car · My White Papers · Organizations I Belong To

Technical Writing · Exposition & Argumentation · Non-fiction Creative Essays · Grammar and Usage of Standard English · The Structure of English · Analysis of Shakespeare

Advanced Professional Papers · The History of the English Language · First Internship: Tutoring in a Writing Workshop · Second Internship: Advanced Instruction: Tutoring Writing

Visual Literacy Seminar (A First Course in Methodology) · Theories of Communication & Technology (A Second Course in Methodology) · Language in Society (A Third Course in Methodology)

UMBC'S Conservative Newspaper: "The Retriever's Right Eye" · UMBC'S University Newspaper: "The Retriever Weekly" · Introduction to Journalism · Feature Writing · Science Writing Papers

Analysis of Literary Language Essay 1 · Analysis of Literary Language Essay 2 · Analysis of Literary Language Essay 2a

Analysis of Literary Language Essay 4 · A Brief Analysis of Edgar Allan Poe's poem "The Raven" · An Analysis of my Own Writing during the Semester

Stephen Dedalus in an effort to rationalize his conflicting emotions in observing a girl at the shore constructs a philosophical argument to explain to himself the difference between beauty and beautiful. Dedalus draws upon parts of arguments in the area of Esthetics developed by philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Saint Augustine, and Thomas Aquinas. Dedalus formulates his esthetic theory from what he defines as "applied Aquinas." This allows him to construct the difference between Moral Beauty, which encompasses the divine and material beauty, which is purely physical.

Stephen Dedalus develops a convincing argument defining beauty by applying his studies of Plato, Aristotle, Saint Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. Stephen notes that one must know whether words in the argument are being used according to literary tradition or whether the words are used according to commonplace traditions. He also notes that there is a difference (135). The phrase, "Beauty is in the eye of the beholder," represents material beauty. Material beauty moves the emotions towards desire and loathing. What one person sees as beautiful may not necessarily be beautiful to another person therefore material beauty is relative. When we see an object that possesses moral beauty, all people agree that the object possesses the qualities of beauty. Moral beauty possesses an element within it that is from the divine, therefore it moves ones emotions towards the spiritual. Moral beauty is universal (137).

The catalyst of his argument is his encounter with a girl on the beach. Stephen is walking along the shore and encounters a girl enjoying the surf with her skirt hiked up to her hips. He describes her long hair as "touched with the wonder of mortal beauty, her face" (123). Stephen continues and describes his own emotions upon observing her that, "...when she felt his presence and the worship of his eyes her eyes turned to him in quiet sufferance of his gaze, without shame or wantonness. Long, long she suffered his gaze and then quietly withdrew her eyes from his and bent them towards the stream..." (123).

The girl blushes as she looks down. Stephen describes himself as turning away from her suddenly with "his cheeks aflame; his body aglow; his limbs trembling" and that he "sung wildly to the sea"(123). Stephen says that, "her image passed into his soul and no word had broken the holy silence of his ecstasy. Her eyes had called him and his soul had leaped to the call. To live to err, to fall, to triumph, to recreate life out of life... the angel of mortal youth and beauty, an envoy from the fair courts of life thrown open before him in an instant of ecstasy the gates of all the ways of error and glory" (123).

This incident allows him to develop his premise. The encounter with the girl represents material beauty. Stephen later understands that he was moved to desire and loathing; loathing is the object we run from and desire is the object we run towards. Stephen says that these "feelings are excited by improper art and are kinetic" or in other words purely reflex reactions of the nervous system and without them there would be no propagation of the species (149). Therefore, the beauty of the girl does not inspire "esthetic emotions not only because they are kinetic" or purely reflex, but that these emotions are "no more than physical" (149). We run from that which we dread and "respond to the stimulus" of what we desire (149). Esthetic emotions are not kinetic but static. "The mind is arrested and raised above desire and loathing" (149).

In order to describe moral beauty Stephen first draws on Plato's definition of beauty. Dedalus says that he believes that Plato describes "beauty as the splendor of truth. Truth is beheld by the intellect, which is appeased by the most satisfying relations of the intelligible: beauty is beheld by the imagination, which is appeased by the most satisfying relations of the sensible" (151). Therefore if beauty is beheld by the imagination and all imaginations collectively are different this would imply "beauty is in the eye of the beholder," and that which one person considers beauty is not the same as what someone else considers beauty.

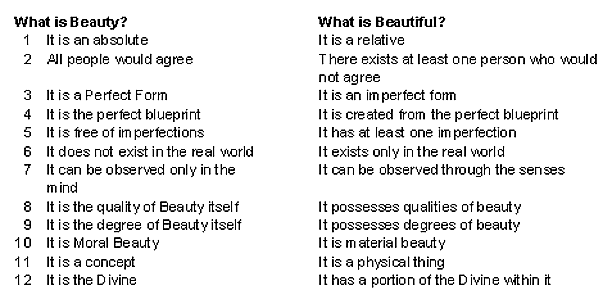

Plato developed what is known as "The Theory of Forms." These forms are perfect structures, perfect arrangements or perfect blueprints of an idea. They are absolutes. Plato said there exists a perfect blueprint of the idea of beauty somewhere beyond space and time, meaning that the form or blueprint does not exist in the physical world. The Form of Beauty is perfect beauty and can only be seen by the mind through insight and not by the senses. An insight of beauty is a perfect mental view of beauty. Plato’s concept of The Form of Beauty is equivalent to Dedalus' concept of Moral Beauty.

Plato argued that Beauty and Beautiful are not synonymous (see figure 1). Beauty is an absolute and only exists as an idea. When we say that something possesses beauty, what we actually mean is that something is beautiful, which is a relative. The object possesses qualities of beauty but it is not the perfect form of beauty. As an example, many people say Brittany Spears is beautiful. But the word "many" implies that there is at least one person on earth who does not consider Brittany Spears beautiful. Therefore Brittany Spears is not the ideal form or the perfect form of beauty. Brittany Spears is not beauty itself because Plato would argue that "pleasure in beauty is disinterested. Pleasure in beauty is desire-free" (Results). The girl Stephen observed falls into the category of beautiful and not beauty itself. Stephen found the girl agreeable, hence he felt desire in observing her.

Then Stephen draws upon Aristotle in order to solve the problem of imagination being different from one person to the next. The next step is to "understand the frame and scope of the imagination, to comprehend the act itself of esthetic apprehension" (151). Now taking this and applying it to the beauty a man sees in a woman, the woman's beauty is not the same for all men observing the same woman and we can dismiss this beauty as the common people's description of beauty which leads to desire and loathing. Therefore this is materialist beauty and not moral beauty. Moral beauty when observed will be considered beautiful by all men and all women. So what we are in search of is universal beauty.

Dedalus continues to build his argument and now draws from Thomas Aquinas. This is logical because Aquinas was fundamentally an Aristotelian. Aquinas argued that there are three things needed for beauty: we require wholeness, harmony and radiance (154). Stephen uses a basket as an example of his object of beauty. In order to see the beauty in the basket the senses frame the basket off from all that surrounds it in space and time. The basket is now "selfbounded and selfcontained" (154). We now see the basket as one and hence satisfying the requirement of wholeness. Next we apprehend the basket as complex, multiple, divisible, separable and made up of its parts, the result of its parts and their sum as a whole is harmonious (155). This satisfies the requirement of harmony. Stephen does not mention that harmony is also associated with symmetry. Things, such as the basket, possess the golden ratio or the symmetry of 33.3 percent are universally accepted by all observers as an esthetic image. 'The radiance Aquinas refers to is the whatness of the thing. The whatness is a luminous, spiritual state, which implies the object has an element of divinity within it” (155).

In summary, an object that an artist creates that is considered an object of beauty do not stimulate the physical emotions of desire or loathing of the observer. The object transcends these emotions in the observer to the spiritual level. The way the object of beauty is created is through the artist's imagination. The inspiration of the object is not the possession of the artist, but rather has been placed in the artist's mind or imagination by God through divine intervention or inspiration. Therefore the object of beauty created by the artist is from the artist's imagination but the object is not a creation by the artist, but is a creation by God who placed the inspiration of the object in the artist's mind. The artist is acting as an agent for God and is acted upon God. Objects that possess beauty possess a spiritual element or divine intervention within them and this is what makes them objects of beauty and not beautiful.

|

Joyce, James. (1916). A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In S. Appelbaum (Ed.). New York: Dover Publications.

Plato on Rhetoric and Poetry. Retrieved November 11, 2004, from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/contents.html

Results for query "Beauty." Retrieved November 11, 2004, from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/contents.html

Saint Augustine. Retrieved November 11, 2004, from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/contents.html

Saint Thomas Aquinas. Retrieved November 11, 2004, from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/contents.html

The Home Page · The Integral Worm · My Resume · My Show Car · My White Papers · Organizations I Belong To

Contact Me · FAQ · Useful Links