Altitude

One

of my many hobbies is the launching of model rockets.† The manufacturer claims that these rockets, which can be as

simple or complex as the builder wishes, are capable of flight to over one

thousand feet.† Of course, this

immediately raised the question: How high did it really go?† I had asked this question in middle school,

but at that time, I did not have the knowledge to answer it (although I did

attempt to do so).† However, I could not

forget the problem and it remained in the back of my mind.† As I became more familiar with trigonometric

functions last year, I determined to derive a theorem to solve the problem.† The simplest method is to simply use

(distance to launch pad)*(tan(angle between the ground and the rocket)) =

height of rocket.† However, this created

an obvious problem; the rockets do not rise perfectly vertically from the

launch pad.† Even if there is negligible

wind on the ground, the wind at five hundred to one thousand feet quickly blows

the rockets a significant distance from the pad. †Because of this, people usually point their launchers into the

wind so that they will drift back to the launcher on the descent.† Either way, the rocket is an unknown

distance away from the launch pad.†

Thus, what I needed was a method of determining the height of the rocket

that would work irrespective of the rocketís horizontal distance or direction

from the launch pad.† Since I was

looking for perpendicular distance above the ground, not the slant height from

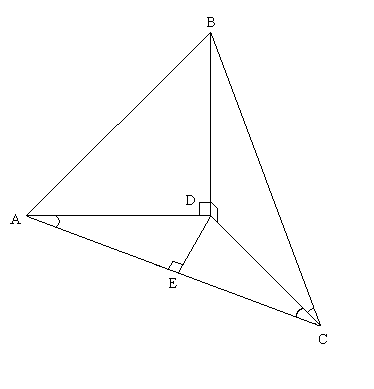

the launch pad, I divided the problem into four right triangles (see figure above or here). Points

A and C represent the two points from which measurements are taken and point B

is the apex of the rocketís climb (or whatever is being measured). †I allowed myself only four known values (one

more than the number of dimensions): the distance from point A to C, the measure

of angle DAE, angle ECD, and DCB.† These

four values can all be determined without knowing the horizontal distance to

point B, which was my goal in the project.†

Looking at the problem backwards, once the length of side DC is known,

this becomes the simple form mentioned earlier.† Hence, the challenge is to determine the length of side DC.† My first method for doing this involved substitution

with the tangents of angles DAE and DCE.†

This method did succeed in determining the length of side DC, but it took

about two pages to develop.† It took the

final form of:

One

of my many hobbies is the launching of model rockets.† The manufacturer claims that these rockets, which can be as

simple or complex as the builder wishes, are capable of flight to over one

thousand feet.† Of course, this

immediately raised the question: How high did it really go?† I had asked this question in middle school,

but at that time, I did not have the knowledge to answer it (although I did

attempt to do so).† However, I could not

forget the problem and it remained in the back of my mind.† As I became more familiar with trigonometric

functions last year, I determined to derive a theorem to solve the problem.† The simplest method is to simply use

(distance to launch pad)*(tan(angle between the ground and the rocket)) =

height of rocket.† However, this created

an obvious problem; the rockets do not rise perfectly vertically from the

launch pad.† Even if there is negligible

wind on the ground, the wind at five hundred to one thousand feet quickly blows

the rockets a significant distance from the pad. †Because of this, people usually point their launchers into the

wind so that they will drift back to the launcher on the descent.† Either way, the rocket is an unknown

distance away from the launch pad.†

Thus, what I needed was a method of determining the height of the rocket

that would work irrespective of the rocketís horizontal distance or direction

from the launch pad.† Since I was

looking for perpendicular distance above the ground, not the slant height from

the launch pad, I divided the problem into four right triangles (see figure above or here). Points

A and C represent the two points from which measurements are taken and point B

is the apex of the rocketís climb (or whatever is being measured). †I allowed myself only four known values (one

more than the number of dimensions): the distance from point A to C, the measure

of angle DAE, angle ECD, and DCB.† These

four values can all be determined without knowing the horizontal distance to

point B, which was my goal in the project.†

Looking at the problem backwards, once the length of side DC is known,

this becomes the simple form mentioned earlier.† Hence, the challenge is to determine the length of side DC.† My first method for doing this involved substitution

with the tangents of angles DAE and DCE.†

This method did succeed in determining the length of side DC, but it took

about two pages to develop.† It took the

final form of:

![]()

Looking for a more straightforward proof, I used the law of sines to more simply determine the length of side DC with the known data, which took the following form:

![]()

†

These two methods each resulted in different theorems, but they return identical answers when working with possible measurements (angles that will actually form triangles such as the ones diagramed). †Thus, over four years after first posing the question, I was finally able to answer it.†

Recently, I have continued this problem by graphing it in three and four dimensions on Mathematica.† I was able to visualize where different altitude readings would be obtained through using the first formula, which made some very interesting graphs.† You can see a still graph below when the angle up to the item (angle BCD in the diagram above) is around half of Pi.†

The plot

exits both the bottom and top of the graph around the middle (where it is flat,

it is going up beyond the box.† To view

the animated version †of this image

(with all four dimensions), see the following files:

The plot

exits both the bottom and top of the graph around the middle (where it is flat,

it is going up beyond the box.† To view

the animated version †of this image

(with all four dimensions), see the following files:

For the tangent theorem:

Standard View with theta rotating from 0 to 2 Pi

A Higher-Resolution View with theta rotating from 0 to Pi

For the law of sines theorem:

Standard View with theta rotating from 0 to Pi

Last Updated: Jan 22, 2003

Copyright 2003 Chris Wellington