Pharmacology

Pharmacology is the science of the

interaction between chemical substances and living tissues. If the chemical is

primarily beneficial, its study falls under the title therapeutics; if

primarily harmful, its study is called toxicology. In either case,

pharmacodynamics defines how the material is absorbed by the body, where it

acts, what its effect is, and how it is metabolized and excreted.

Pharmacology is the science of the

interaction between chemical substances and living tissues. If the chemical is

primarily beneficial, its study falls under the title therapeutics; if

primarily harmful, its study is called toxicology. In either case,

pharmacodynamics defines how the material is absorbed by the body, where it

acts, what its effect is, and how it is metabolized and excreted.

Pharmacologists determine the

therapeutic index of drugs, that is, the relative benefit to toxicity at

various doses. This helps define the dosage of  a drug that will most benefit a sick

person. They also study how various conditions affect the excretion of drugs.

For example, many drugs are more slowly metabolized in older persons, so these

drugs need to be administered less frequently. Because many chemicals are

excreted by the kidney, persons with kidney disease may have impaired drug

excretion.

a drug that will most benefit a sick

person. They also study how various conditions affect the excretion of drugs.

For example, many drugs are more slowly metabolized in older persons, so these

drugs need to be administered less frequently. Because many chemicals are

excreted by the kidney, persons with kidney disease may have impaired drug

excretion.

Doctors who specialize in

pharmacology are called clinical pharmacologists. Pharmacists who practice in

hospitals also specialize in pharmacology, and they can advise doctors on the

optimal use of medicinal drugs.

Pharmacy is practice of compounding

and dispensing drugs; also the place where such medicinal products are

prepared. Pharmacy is an area of materia medica, the branch of medical science

concerning the sources, nature, properties, and preparation of drugs.

Pharmacists share with the chemical and medical profession responsibility for

discovering new drugs and synthesizing organic compounds of therapeutic value.

In addition, the community pharmacist is increasingly called upon to give

advice in matters of health and hygiene.

Pharmacy is practice of compounding

and dispensing drugs; also the place where such medicinal products are

prepared. Pharmacy is an area of materia medica, the branch of medical science

concerning the sources, nature, properties, and preparation of drugs.

Pharmacists share with the chemical and medical profession responsibility for

discovering new drugs and synthesizing organic compounds of therapeutic value.

In addition, the community pharmacist is increasingly called upon to give

advice in matters of health and hygiene.

The cup Hygeia, daughter of

Asklepius is the symbol of pharmacy. In antiquity, pharmacy and the practice of

medicine were often combined, sometimes under the direction of priests, both

men and women, who ministered to the sick with religious rites as well. Many

peoples of the world continue the close association of drugs, medicine, and religion

or faith. Specialization first occurred early in the 9th century in

the civilized world around

rembert dodonaeus 1517 – 1585

rembert dodonaeus 1517 – 1585

was born in

was born in

Jan Baptista van HELMONT 1580 – 1644

Belgian doctor and chemist, the first scientist

to distinguish between gases and air. He pioneered in experimentation and an early form of biochemistry,

called iatrochemistry. Helmont believed that

the basic elements of the universe are air and water. He believed that plants

are composed only of water and claimed to have proved this theory by planting a

willow of known weight in soil of known weight and weighing the willow and the

soil five years later. The willow had gained 76.7 kg and the soil had lost

practically no weight. He suggested that the willow had gained weight by taking

in water alone. For the modern explanation of his experiment ð Photosynthesis

Belgian doctor and chemist, the first scientist

to distinguish between gases and air. He pioneered in experimentation and an early form of biochemistry,

called iatrochemistry. Helmont believed that

the basic elements of the universe are air and water. He believed that plants

are composed only of water and claimed to have proved this theory by planting a

willow of known weight in soil of known weight and weighing the willow and the

soil five years later. The willow had gained 76.7 kg and the soil had lost

practically no weight. He suggested that the willow had gained weight by taking

in water alone. For the modern explanation of his experiment ð Photosynthesis

Philippus Aureolus paracelsus (Theophrastus Bombastus von

Hohenheim) 1493 – 1541

German doctor and chemist.

Quarrelsome and vitriolic, Paracelsus defied the medical tenets of his time,

asserting that diseases were caused by agents that were external to the body

and that they could be countered by chemical substances.

German doctor and chemist.

Quarrelsome and vitriolic, Paracelsus defied the medical tenets of his time,

asserting that diseases were caused by agents that were external to the body

and that they could be countered by chemical substances.

Many of his remedies were based on

the belief that “like cures like”, and in this respect he was a precursor of

homoeopathy.

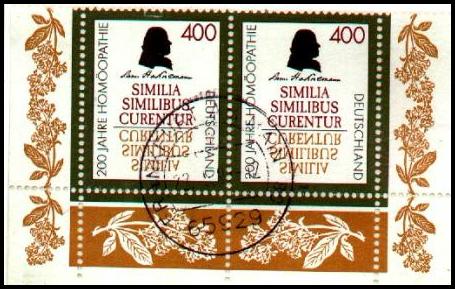

Homoeopathy

Homoeopathy is system of medical

practice based on the principle that diseases can be cured by drugs that

produce in a healthy person the same pathological effects that are symptomatic

of the disease. This doctrine was first formulated by the German doctor Samuel Hahnemann in 1796. Homoeopaths

also believe that small doses of a drug are more efficacious than large doses.

Although homoeopathy is discounted by most doctors, it is still widely

practiced.

Homoeopathic diagnosis and therapy

treats the whole body as a unified organism. Its basis lies in the 19th

century, when Samuel Hahnemann defined disease as “an aberration from the state

of health”, which cannot be mechanically removed from the body. In 1881

Hahnemann called for healing to be quick, reliable, and  permanent and he believed that

holistic medicine embraced all of these attributes. Disease was considered to

be of two types: acute, which temporarily disabled the

permanent and he believed that

holistic medicine embraced all of these attributes. Disease was considered to

be of two types: acute, which temporarily disabled the  person but which could be overcome

with time and treatment, and chronic conditions, a series of acute episodes

that could with time seriously disable the patient. In treating acute illness,

the homoeopath is charged with four responsibilities: a thorough knowledge of

the disease, its etiology, pathology, prognosis, and diagnosis; a thorough

knowledge of the medicinal power of drugs; the ability to relate the power of

drugs to the patient's condition; an ability to foresee barriers between the

patient and good health and a knowledge of how to reduce such barriers.

person but which could be overcome

with time and treatment, and chronic conditions, a series of acute episodes

that could with time seriously disable the patient. In treating acute illness,

the homoeopath is charged with four responsibilities: a thorough knowledge of

the disease, its etiology, pathology, prognosis, and diagnosis; a thorough

knowledge of the medicinal power of drugs; the ability to relate the power of

drugs to the patient's condition; an ability to foresee barriers between the

patient and good health and a knowledge of how to reduce such barriers.

The treatment prescribed by the

homoeopathic doctor is largely based on the idea that the body contains a vital

natural force which has the power to affect recovery. The basis of homoeopathy

adheres to four basic laws. “SIMILIA

SIMILIBUS CURENTUR” The law of similar, “like cures like”;

a drug that produces symptoms of a disease in a healthy person will cure a

person who has the disease. Significantly, this does not have a sound basis in

conventional pharmacology. The law of potentiation maintains that high doses of

medicine  intensify disease symptomatology,

whereas small doses tend to strengthen the body's defense mechanisms.

There-fore a cure does not lie in the quantity of medicine but in its quality,

and invariably in subtle aspects of the curative treatment. This is why most

homoeopathic remedies used today require elaborate prescription and formulation

regimes. The law of cure occurs from above downwards, from within outwards,

from an important organ to a less important one, and in the reverse order of

the symptoms. Single remedy medication consists of one pure drug at a time,

never in mixtures that could potentially contain harmful compounds.

intensify disease symptomatology,

whereas small doses tend to strengthen the body's defense mechanisms.

There-fore a cure does not lie in the quantity of medicine but in its quality,

and invariably in subtle aspects of the curative treatment. This is why most

homoeopathic remedies used today require elaborate prescription and formulation

regimes. The law of cure occurs from above downwards, from within outwards,

from an important organ to a less important one, and in the reverse order of

the symptoms. Single remedy medication consists of one pure drug at a time,

never in mixtures that could potentially contain harmful compounds.

The modern pharmacist deals with

complex pharmaceutical remedies far different from the elixirs, spirits, and

powders described in the Pharmacopoeia of London 1618 and the Pharmacopoeia of

Paris 1639. Most countries with a regulated health-care system prepare a

compendium, or formulary, of authorized drugs and formulae.

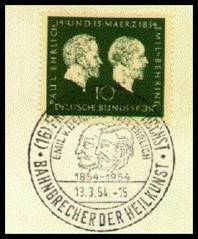

The First Anti-Infective Drugs

The first drug to cure an often

fatal infectious disease was the “magic bullet” of the German bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich. Convinced that arsenic

provided the clue to a cure for the venereal disease syphilis, Ehrlich synthesized hundreds of organic

The first drug to cure an often

fatal infectious disease was the “magic bullet” of the German bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich. Convinced that arsenic

provided the clue to a cure for the venereal disease syphilis, Ehrlich synthesized hundreds of organic  arsenical compounds. These he

injected into mice previously infected with the causative organism, Spirochaete pallidum. Some of the

605 compounds tested showed some promise of success but too many mice died. In

1910 Ehrlich made and tested compound number 606, arsphenamine. It cured his

infected mice and, more importantly, left them in good health.

arsenical compounds. These he

injected into mice previously infected with the causative organism, Spirochaete pallidum. Some of the

605 compounds tested showed some promise of success but too many mice died. In

1910 Ehrlich made and tested compound number 606, arsphenamine. It cured his

infected mice and, more importantly, left them in good health.

Ehrlich now had the problem of

making his compound in quantity, suitably packaged for injection, and

distributing it for use. He sought the help of the

Cancellation of F.W. Sertürner, who

discovered Morphine

![]()