A SALUTE TO MODERN BLACK HISTORY

With Updated Voice Message From Mr. Vincent Scott

Can't hear voice message? CLICK HERE to download windows media player 11. (Windows XP Only)

If you don't have Windows XP CLICK HERE to download Windows Media Player 9 (For Windows 98 SE, Me, and 2000).

Introduction by Mr. Vincent L. Scott

VERY IMPORTANT!!

CLICK HERE AND READ INTRODUCTION FIRST.

VERY IMPORTANT!!

CLICK HERE AND READ INTRODUCTION FIRST.

EARLY IMMIGRATION AND SLAVERY

Most of the earliest black immigrants to the Americas were natives of Spain and Portugal—men such as Pedro Alonso Niño (1468–1505), a navigator who accompanied Columbus on his first voyage, and the black colonists who helped Nicolás de Ovando (1460?–1518) form the first Spanish settlement on Hispaniola in 1502.

The name of Nuflo de Olano (b. 1490?) appears in the records as that of a black slave present when Vasco Núñez de Balboa sighted the Pacific Ocean in 1513. Other blacks served with Hernán Cortés when he conquered Mexico and with Francisco Pizarro when he marched into Peru.

Iberian Blacks

Estebanico (c. 1500–38), one of the survivors of Pánfilo de Narváez’s unfortunate expedition to Florida in 1527, was a black. With three companions, he spent eight years traveling overland to Mexico City, learning several Indian languages in the process. Later, while exploring what is now New Mexico, he lost his life in a dispute with the Zuñi Indians. Juan Valiente (d. 1553), another black, led Spaniards in a series of battles against the Araucanian Indians of Chile between 1540 and 1546. Although Valiente was a slave, he was rewarded with an estate near Santiago and control of several Indian villages. Between 1502 and 1518, Spain shipped out hundreds of Spanish-born Africans, called Ladinos, to work as laborers, especially in the mines. Opponents of their enslavement cited their weak Christian faith and their penchant for escaping to the mountains or joining the Indians in revolt. Proponents declared that the rapid diminution of the Indian population required a consistent supply of reliable workhands.

Free Spaniards were reluctant to do manual labor or to remain settled (especially after the discovery of gold on the mainland), and only slave labor could assure the economic viability of the colonies.

Beginning of the African Slave Trade

By 1518, the demand for slaves in the Spanish New World was so great that King Charles I of Spain (who, as Holy Roman Emperor, was known as Charles V), sanctioned the direct transport of slaves from Africa to the American colonies. The slave trade was controlled by the Crown, which sold the right to import slaves (asiento) to entrepreneurs.

By the 1530s, the Portuguese were also using African slaves in Brazil. From then until the abolition of the slave trade in 1870, at least 10 million Africans were forcibly brought to the Americas: about 47 percent of them to the Caribbean islands and the Guianas; 38 percent to Brazil; and 6 percent to mainland Spanish America. About 4.5 percent went to North America, roughly the same proportion that went to Europe.

The greatest proportion of these slaves worked on plantations producing sugar, coffee, cotton, tobacco, and rice in the tropical lowlands of northeastern Brazil and in the Caribbean islands. Most of them came from the sub-Saharan states of West and Central Africa, but by the late 18th century the supply zone extended to southern and East Africa as well.

Impact of Slavery

Slavery in the Americas was generally harsh, but it varied from time to time and place to place. The Caribbean and Brazilian sugar plantations required a consistently high supply of labor for centuries. In other areas—the frontiers of southern Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, and Colombia—slavery was relatively unimportant to the economy.

Two slaves running away from (most likely) patrollers. During slavery, slaves had horrible lives, had worse than bad living conditions, and were constantly tormented by overseers and the master. If a slave was lucky, he would get a floor... Many slaves felt like they were forced to run away.

To tame the wilderness, build cities, establish plantations, and exploit mineral wealth, the Europeans needed more laborers than they could recruit from among their own metropolitan masses. In the early 16th century, the Spanish tried unsuccessfully to subjugate and enslave the native populations of the West Indies. Slavery was considered the most desirable system of labor organization because it allowed the master almost absolute control over the life and productivity of the laborer. The rapid disintegration of local indigenous societies and the subsequent decimation of the native Indians by warfare and European diseases severely exacerbated the labor situation, increasing the demand for imported workers.

African slaves constituted the highest proportion of laborers on the islands and circum-Caribbean lowlands where the native population had died. The same was true in the northeastern coastlands of Brazil—especially the rich agricultural area called the Reconcavo, where the seminomadic Tupinamba and Tupiniquim Indians resisted effective control by the Portuguese—and in some of the Leeward Islands such as Guadeloupe and Dominica, where the Caribs waged a determined resistance to their expulsion and enslavement. In areas of previously dense populations, such as parts of central Mexico or the highlands of Peru, a sufficient number of the Indian inhabitants survived to satisfy a major part of the labor demands of the new colonists. In such cases African slaves supplemented coerced Indian labor.

THE SLAVE ERA

The extensive use of black African labor during the 16th and 17th centuries on profitable Brazilian and Caribbean sugar plantations provided a model for European colonists in North America, where Indians and white indentured servants were insufficient to meet the demands for agricultural labor.

Although Africans served as guides and soldiers in the initial Spanish conquest of Mexico, most blacks brought to North America were used to produce the export crops—tobacco, rice, indigo, and cotton—that became the major source of the wealth extracted by European nations from their colonies. The English settlers of North America only gradually turned to black slavery to solve their labor shortage. Spain brought at least 100,000 Africans to Mexico during the 16th century, but England did not extensively engage in the slave trade until the Royal African Co. was established in 1663. Although a trickle of Africans began arriving in English North America in 1619, their status was initially similar to that of the white indentured servants, who remained the backbone of the agricultural labor force until the end of the century. As white workers improved their status during this period, however, both free and bonded blacks were subjected to new laws punishing slave disobedience, prohibiting racial intermarriage, restricting manumission, and otherwise ensuring that the political rights and economic opportunities granted to whites would not be extended to Africans or their descendants.

Resistance

Blacks resisted enslavement from the time of capture in Africa but, outnumbered by whites, North American slaves were less likely than Brazilian or Caribbean ones to engage in massive rebellions.

American slaves were

tortured or killed if caught

trying to run away.

Africans in North America typically underwent “seasoning” in the West Indies and a “breaking” process on the mainland, which was designed to supplant African cultural roots with the attitudes and habits of obedience required for slave labor. Retention of African skills and social patterns was not as common among North American slaves as among their Latin American counterparts, who were more likely to be born in Africa or have extensive contact with African-born slaves. Only in South Carolina, where slaves became a majority of the population, did planters commonly seek slaves from particular regions of Africa who possessed desired skills, such as the knowledge of rice cultivation. More often, white slaveholders attempted to suppress African culture, believing it was easier to control slaves who spoke English and depended on the skills and knowledge instilled in them by whites. These efforts were not completely successful, however. Slaves Africanized English, Christianity, and other aspects of Western civilization, thereby creating their own unique culture that combined African with European elements.

Efforts to return to Africa or to establish Maroon (slave) colonies in North America became less common as the proportion of African-born slaves declined, but resistance continued under the leadership of slaves and free blacks, who used their knowledge of white society to improve the status of blacks. Despite the restrictions white masters placed on the education and religious activity of slaves, literacy and Christianity often became vehicles for individual and collective resistance, both to brutal treatment and to enslavement itself.

During the winter of 1777-78, Blacks served in the battle of Valley Forge freezing, starving, and dying.

Moreover, tens of thousands of slaves fled behind British lines in response to Sir Henry Clinton Philippsburg Declaration that "Every NEGRO who shall desert the Rebel Standard, [is granted] full security to follow within these Lines, any Occupation which he shall think proper."

The American Revolution and Black Rebellions

During the 18th century, black rebelliousness received a new stimulus from the growing popularity among whites of democratic and egalitarian ideas. Slaves exploited the divisions in white society during the American Revolution. Thousands responded to a royal offer of freedom for those who fought with the British, and after the war several thousand black Loyalists went to Canada, most of them settling in Nova Scotia.

About 5000 blacks served in the Continental Army. After the war, revolutionary ideology and Quaker pietism inspired new antislavery activities by both blacks and whites. Blacks petitioned state legislatures for freedom, better treatment, or repatriation to Africa. The self-trained black scientist Benjamin Banneker argued against Black Inferiority in a famous correspondence with U.S. President Thomas Jefferson.

Benjamin Banneker used his knowledge of the stars and air to become the first person to perdict the Weather.

This helped farmers in their production of planting crops.

He also had a photografic memory and was able to draw the lost blueprints of the Whitehouse in Washington D.C. from memory.

The liberalization of white attitudes was reversed in the South as a result of the profits made possible by the invention of the cotton gin. During the 18th century, the spread of cotton cultivation to the Deep South and southwestern states fostered the rise of an archconservative southern political order based on the use of slave labor. Despite this retreat, however, ideas drawn from the American, French, and Haitian revolutions, as well as from Christian idealism and African folk beliefs, remained evident in 19th-century slave resistance, especially the major conspiracies led by Gabriel Prosser in Virginia (1800) and Denmark Vesey in South Carolina (1822). The bloody Nat Turner Rebellion (1831) prompted increased repression of slave activities, although small-scale resistance—running away, tool breaking, sporadic violence—continued to interfere with plantation operations.

Semifree Blacks

Although more than 90 percent of the black population in the U.S. was enslaved at the time of the 1790 census, the small population of freed blacks had already established its own social institutions and had begun efforts to improve the conditions of the race. Most of these efforts were centered in cities, which offered more liberty to black residents than did rural areas. Even black slaves had some freedom of movement in the cities, and they generally possessed greater skills and had better access to information than was common on plantations. By the end of the 18th century, Philadelphia blacks under the leadership of Richard Allen had founded what became (1816) the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and blacks in New York City had formed the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. By that time black Baptist churches had also been established in various other communities, mostly in the South. In Boston, Philadelphia, and Providence, R.I., black Masonic lodges had been organized under the leadership of Prince Hall (1748–97).

Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church

By the time of the Turner Rebellion, black urban communities sustained a variety of churches, fraternal orders, schools, self-help groups, and political organizations. Although literacy was still uncommon, these institutions fostered self-confidence among black leaders and encouraged them to express their concerns to the general population. The determination of blacks to decide their own destiny was revealed in their newspapers, such as Freedom’s Journal, founded in 1827, and in militant pamphlets, including Appeal (1829) by David Walker (1785–1830). During the 1830s black leaders gathered annually in national conventions to discuss strategies for racial advancement.

Nat Turner led a Slave Rebelion that killed 50 whites.

Efforts by blacks to improve their conditions ranged from the adoption of prevailing white values to attempts to reform or escape American society. The black shipowner Paul Cuffee (1759–1817), for example, favored a return to Africa and in 1815 succeeded in transporting a small group of free blacks to Sierra Leone. In 1817, however, when whites in the newly formed American Colonization Society (ACS) announced their desire to return free blacks to Africa, black representatives assembled by Richard Allen firmly rejected the idea, arguing that they should not abandon their enslaved fellow blacks. In subsequent years, blacks continued to discuss the option of immigrating to Canada, Latin America, or Africa. Although the ACS established a colony in Liberia in 1822, foreign colonization ventures received little support until the 1850s.

Paul Cuffee (1759–1817), succeeded in transporting some blacks to Sierra Leone.

Discrimination against manumitted slaves was intense throughout the U.S. Although blacks could vote in some northern states in the years after the Revolution, the extension of voting rights to propertyless men was accompanied by new restrictions on black political participation, landownership, and social contact with whites. By the 1830s, most southern and some northern states restricted or prohibited the entry of free blacks; Ohio law required entering blacks to post $500 bonds. An attack on the Cincinnati black community by a white mob in 1829 was followed in the next few years by similar riots in other northern cities, where white workers resented competition from blacks for jobs. Although southern free blacks lived in societies that feared and often restricted their presence, they had greater opportunities than northern blacks to work as artisans and even to acquire property. In New Orleans, La., for example, 753 blacks owned slaves, according to the 1830 census. Most urban blacks lived on the margins of society, however, barred from public educational facilities, good housing, and legal protection. For thousands of antebellum blacks, Canada (where slavery was outlawed in 1833) and, to a lesser degree, Mexico became places of refuge.

Abolitionist Movement

Increased discrimination, combined with the growth of black literacy, institutional strength, and economic resources, encouraged a trend toward greater militancy after 1830. Impatience with gradualist plans to end slavery prompted the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison to advocate immediate abolition and, with black help, to found the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. Many black activists later became disenchanted with Garrison’s notion that slavery could be ended by moralistic arguments; instead they stressed the need for political action and, ultimately, violent resistance. The growing militancy was displayed in 1839, when black communities raised funds to defend Africans in the Amistad Case. Some blacks broke with Garrison to join the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, while others worked within all-black self-help societies and local groups established to help runaway slaves.

Growing Activism

THE REV. HENRY HIGHLAND GARNET

Image Credit: © Smithsonian Instiution, Courtesy National Portrait Gallery; via PBS website, Africans in America

HARRIET TUBMAN SOJOURNER TRUTH

Image Credit: Courtesy of the History Channel

Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Maria Stewart (1803–79) were active abolitionists. Tubman and others helped slaves escape through the Underground Railroad.

MARIA STEWART

"How long shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles?"

Maria Stewart wrote for the Liberator, a paper that was very influentual in changing attitudes andending slavery in the U.S. She encouraged women not to be dependent on men, and to start their own businesses. She thought that women should rely only on themselves to change things in society.Unfortunately, a black woman writing at that time was scorned, and she was forced to leave the city entirely due to the violent reaction against her, which even came from black men.

Image Credit: Courtesy of the Goddess Cafe

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (see Fugitive Slave Laws) increased pessimism among blacks about the possibility of a peaceful end to slavery. Several violent clashes occurred when armed blacks tried to protect escaped slaves or sought to free captured fugitives. Abolitionist resistance in Boston was so strong that 2000 soldiers were required in 1854 to escort Anthony Burns, an escaped slave, to a ship that returned him to the South. Black pessimism was further strengthened in 1857 by the Dred Scott Case ruling that blacks were not considered U.S. citizens. During this period, black militants such as Garnet and Delany decided that blacks could progress only by remaining separate from whites, and in 1859 Delany led an exploratory expedition to Africa to prepare the way for future African-American colonies. Although these advocates of black nationalism were a minority within the antebellum black community, they reflected the growing belief that slavery was a basic part of the U.S. political system.

Thus, the white abolitionist John Brown found many blacks in sympathy with his plans to spark a slave uprising, and five blacks later participated in Brown’s unsuccessful raid on the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Va. (now West Virginia), in 1859.

CIVIL WAR, RECONSTRUCTION, AND URBAN MIGRATION

Although most northern whites did not expect the Civil War to result in the elimination of slavery, black abolitionists offered their services to the Union cause with that end in mind. Northern policy regarding black enlistments was inconsistent, however, for President Abraham Lincoln and other leaders hoped to preserve the Union without abolishing slavery or ending discrimination in the North.

Blacks in Union Service

BLACKS IN THE CIVIL WAR

After 135 years, the Battle of Fort Pillow still raises a heated debate with students of the American Civil War. To this day, it remains a black stain on the name of an "untutored genius of war," Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Because this (in my mind) was a carefully orchestrated massacre of black Union soldiers, period.

BLACKS IN THE CIVIL WAR

Even after gaining acceptance into military service, however, black soldiers suffered racist treatment from many of their white officers. The Confederates generally treated their black prisoners with brutality. When several hundred black troops at Fort Pillow, Tenn., were captured in 1864, they were murdered by the southern forces.

Congressional Medal of Honor

William Carney was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts. He was a member of Company C, 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry. On July 18, 1863, during the Battle of Fort Wagner, South Carolina, which involved the all-Black 54th and 55th Massachusetts Colored Regiments, Commander Robert G. Shaw was shot down. A few feet from where he fell laid Sergeant Carney. Summoning all of his strength, Carney held aloft the colors and continued the charge. Having been shot several times, he kept the colors flying high, and miraculously retreated his regiments. Although he made it out alive, many of his comrades did not. For in the deadly battle, over 1,500 Black troops died. On this day in 1900, Sergeant William H. Carney was issued the Congressional Medal of Honor, some say this made him the first Black to ever win the coveted award.

BLACKS IN THE CIVIL WAR

By the end of the war, the Union had become dependent on the services of 186,000 black soldiers and sailors, 21 of whom received the Medal of Honor, and Congress acceded to black demands for equal pay, retroactive to the date of enlistment.

The slaves’ desire for freedom was demonstrated during the war by escapes from plantations threatened by Union troops. In the early part of the conflict, some northern commanders returned slaves to their masters, while others forced escapees to work for the Union Army. In a few instances, blacks were allowed to farm land confiscated from white planters, but most of these lands were returned to their former owners at the end of the war. The Fredmen’s Bureau, established in March 1865, assumed responsibility for the welfare of free slaves, but a clear national policy regarding the future status of blacks emerged only gradually.

Reconstruction

Despite the Union victory, southern blacks experienced severe restrictions on their freedom after the Civil War. Many hoped that they would be given confiscated or abandoned lands and thereby gain economic independence, but white landowners succeeded in passing “black codes” to restrict black landownership and freedom of movement. This southern recalcitrance prompted Congress to extend the life of the Freedmen’s Bureau and to pass civil rights legislation protecting black rights. President Andrew Johnson’s veto of this legislation, and the subsequent defeat of his Democratic party in the 1866 congressional elections, led radical Republicans to take charge of the Reconstruction of the South.

P.B.S. PINCHBACK

Although two black men—Hiram R. Revels and Blanche K. Bruce (1841–98)—became U.S. senators, and blacks held some 15 seats in the House of Representatives, blacks never controlled any state government. The official corruption that was later attributed to black rule in the South was merely part of a national trend toward the exploitation of government by business interests. In general, southern blacks attempting to exercise their newly acquired rights faced growing terrorism from such groups as the Ku Klux Klan.

The Ku Klux Klan

Erosion of Black Rights

After the final withdrawal of northern troops from the South in 1877, intense racial discrimination and depressed economic conditions prompted many blacks to leave. Moreover, Supreme Court decisions during the 1880s and ’90s drastically undermined their protection under the 14th Amendment. The Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision (1896), approving separate public facilities for blacks, marked the culmination of this process. Black economic rights were eroded through crop lien laws (which gave white landowners title to black farm production), through debt peonage, and through vagrancy laws that prevented blacks from refusing low-paying jobs. During the 1890s black and white farmers joined to build a strong Populist alliance (see People’s Party), but this coalition fell apart after 1896 as a result of intimidation and white susceptibility to racist Democratic appeals.

By the end of the century, southern white leaders had begun to vitiate the 15th Amendment’s guarantees of black voting rights through devices such as poll taxes and literacy tests. Black political and economic freedom was also suppressed by sheer terror; more than 1000 blacks were put to death by lynching during the 1890s. A black educator, Booker T. Washington, reacted to this erosion of black rights by advocating a policy of racial accommodation. He urged blacks not to emphasize the goals of social integration and political rights but instead to acquire the occupational skills that would facilitate economic advancement.

BOOKER T. WASHINGTON

Urban Migration

The deteriorating conditions in the South after Reconstruction sparked numerous waves of black migration to the North and West. Although the majority of black migrants went to the eastern seaboard states and to the Midwest, blacks also participated in the general westward movement.

MIGRATION TO THE WESTERN STATES

A major exodus into Kansas occurred in 1879, and other movements resulted in the formation of all-black towns in Oklahoma and other western states. Black migrants also moved to the far West. Mexican-born blacks were among the founders of Los Angeles, and black "buffalo soldiers" fought Indians in order to open up a large part of the Southwest for white settlement.

By 1900 the distribution of the black population had changed in significant ways from what it had been before the Civil War. Although still overwhelmingly concentrated in the South, almost one-fourth of all blacks now lived in urban areas. In the northeastern and western states, more than three-fourths were urbanites. The largest concentrations were in Washington, D.C.; Baltimore, Md.; New Orleans, La.; Philadelphia; New York City; and Memphis, Tenn.—each of which had more than 40,000 black residents.

MIGRATION TO THE NORTHERN STATES

Urban blacks, drawn by economic opportunities available in the cities, had to contend with considerable discrimination and hostility from white workers. Faced with competition from European immigrants, they were generally excluded from unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor. Even blacks who worked in personal-service occupations encountered growing competition from immigrants and increasing hostility from their affluent white clientele. Both American blacks and the much smaller black population in Canada (about 17,000 in 1900) felt a declining support by whites for racial reform and a spreading acceptance of pseudoscientific doctrines of northern European superiority.

***** SPEACIAL NOTE *****

People would like to think that the doctrines of European Superiority are a thing of the past, this is not true HOWEVER...

...IN KEEPING WITH THE CONTRACT REQUIREMENTS OF THE ANGELFIRE WEB SITE THIS WEB PAGE IS USED ONLY TO ENLIGHTEN OUR COMMUNITIES THEREFORE WE WILL NOT AND CAN NOT (Not even if we wanted to) LINK TO THESE WEB PAGES, http://www.resist.com/ OR www.natall.com WE DO NOT CONDONE ANY OF THE DOCTRINES EXPRESSED ON THESE SITES. WE ARE ONLY WANTING TO LET EVERYONE KNOW THAT THE PSEUDOSCIENTIFIC DOCTRINES OF NORTHERN EUROPEAN SUPERIORITY ARE STILL OUT THERE AND THE MENTIONING OF THE WEBPAGES ABOVE ARE FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY!!

SIGNED: MICHEAL MONTGOMERY

P.S. IF THERE IS ANY PROBLEM OR IF WE HAVE BROKEN OUR CONTRACT AGREEMENT PLEASE CONTACT US AT mmontgomery@australia.edu We will be more than happy to correct this.

BLACK SOCIETY IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY

Mary Church Terrell, women's rights activist, was elected first president of the National Association of Colored Women in 1896, She also was a charter member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Click on the Image above to learn more about Mary Church Terrell and the early days of the battle against segregation laws addopted by the United States Supreme Court 1896. (Brown vs. Board of Education Exhibit)

The movement of blacks from rural to urban areas led to profound changes in African-American society. The expanding black urban communities offered the migrants greater freedom than the rural South and provided a broader range of social institutions and educational opportunities. The cities were particularly attractive to blacks who had been educated at Howard, Fisk, Atlanta, Hampton, and other black colleges established during the 19th century. Some intellectuals, including Ida B. Wells (1862–1931), Mary Church Terrell (1863–1954), W. E. B. Du Bois, and William Monroe Trotter (1872–1934), departed from the accommodationism of Washington to pursue equal rights through various protest groups, such as the all-black Niagara Movement and the interracial National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Ida B. Wells |  W.E.B. DuBois |  Mr. William Monroe Trotter A man that stood up for what he believed, no matter what the circumstances might bring. He went out on his own and went against his people because he did not believe in bowing down to "whites" as his counter partner Booker T. Washington believed his people should do. |

Growing Self-Awareness

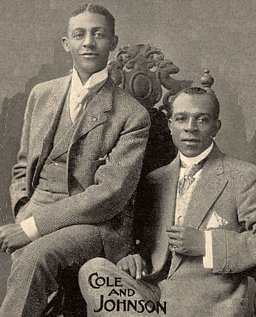

The growth in the size and literacy of the urban black populace stimulated cultural and intellectual activity. Newspapers and magazines published by blacks appeared in all substantial black communities. The composers Scott Joplin, W. C. Handy, and J. Rosamond Johnson (1873–1954), brother of the writer James Weldon Johnson, and the poet-novelist Paul Laurence Dunbar were among the black artists who achieved prominence at the turn of the century. Numerous other musicians and writers labored more anonymously as they combined Western musical styles with rhythmic and melodic forms rooted in Africa and in slavery to create African-American jazz.

Scott Joplin The "King of Ragtime" music |  W. C. Handy "Father of the Blues" |  J. Rosamond Johnson (Lower Right) With Bob Cole Copyrighted 1992, 2000 by Thomas L Morgan |

At the end of the 19th century, ambivalence about “unrefined” black folk culture and emerging black urban life-styles existed among longer established and more educated black residents. As these communities absorbed a stream of new migrants in the decades after Reconstruction, churches that were dominated by older residents were supplemented by less formal Baptist or Pentecostal churches that appealed to poor, sometimes illiterate, new arrivals from the rural South. Tensions were evident between the old residents, who frequently performed personal services for whites, and the new migrants, who had difficulty competing for such jobs. By the early 20th century, however, many black communities had become large enough to support a minority of black professionals and business people, and earlier deference to white standards among relatively successful blacks gradually gave way to an increasing sense of racial pride and social cohesion. Black fraternal orders, political organizations, social clubs, and newspapers published by blacks asserted an urban black consciousness that became the foundation for the militancy and cultural innovations of the 1920s.

World War I

World War I marked a turning point in African-American history by hastening the long-term process of black urbanization and institutional development. When black migrants came to urban areas to take industrial jobs vacated by white soldiers, the resulting expansion of the black urban population opened still further the business and professional opportunities for blacks. Even before the war, the emerging black middle class had begun to identify its own interests with those of less affluent blacks, who were their clientele.

A. PHILIP RANDOLPH

These sentiments became more evident as blacks self-consciously reacted to white racism with expressions of racial pride and unity. College-educated blacks—Du Bois called them “the talented tenth”—were still few in numbers (only 2132 blacks were in college in 1917), but they were more and more likely to have received academic rather than vocational training and were thereby better able to provide articulate political and cultural leadership. These educated blacks did not agree on support for the war—the labor leader A. Philip Randolph and the socialist Chandler Owen (1889–1967) vigorously opposed it—but were united in the view that blacks should use the war as an opportunity to make racial gains. The majority of the 370,000 black servicemen were assigned to support units during World War I, but some all-black regiments saw extensive combat duty. The 369th Infantry Regiment was the first Allied regiment to reach the Rhine River; the regiment was awarded the Croix de Guerre by France for distinguished service during the war. Black servicemen came home from the war with a determination to demand the respect of the nation for which they had fought.

The Postwar Years

Even as blacks returned, however, white opposition to black gains became more intense.

In 1917 more than 200 blacks were killed in East Saint Louis, Ill., by a white mob that invaded the black community. During the same year, 63 black soldiers in Houston, Tex., were summarily court-martialed and 13 hanged without benefit of appeal after a black battalion rioted in reaction to white harassment. After the war, many black soldiers in uniform were attacked and some killed by whites seeking to reinforce traditional patterns of racial domination. During the “Red Summer” of 1919, antiblack riots occurred in Longview, Tex.; Washington, D.C.; Chicago; Knoxville, Tenn.; and Omaha, Nebr. These events further stimulated blacks to defend their rights and support outspoken leaders.

MARCUS GARVEY

The most popular militant black leader was a Jamaican immigrant, Marcus Garvey, who in 1916 established an international organization with headquarters in New York City. His Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) had a membership ranging from 2 to 4 million people. By 1919 he had also established a steamship corporation, the Black Star Line, to pursue trade with Africa. Garvey’s popularity, however, made him a target of attacks from black civil rights leaders and brought him under surveillance by the U.S. government. In 1922, amid mounting controversy, he was arrested for mail fraud in connection with his steamship line. His subsequent conviction and imprisonment, and his deportation in 1927, resulted in a rapid decline of the UNIA.

CLAUDE McKAY Click Picture to learn how to write Poetry. |  JEAN TOOMER Portrait by Weinold Reiss Click on picture to read about Jean Toomer's Life and Career |

The Harlem Renaissance

Garvey’s rise and fall was only one aspect of the growth of racial pride and awareness that characterized the 1920s. As he drew support from black workers and those who owned small businesses, a cultural movement—the Harlem Renaissance—was gaining support from black intellectuals (see also American Literature: Harlem Renaissance). The Jamaican-born poet and novelist Claude McKay was the first black literary figure of the 1920s to attract a large white audience. The innovative novel Cane (1923) by Jean Toomer (1894–1967) voiced the common theme of the Harlem Renaissance in its identification with the lifestyles of the black poor.

Although Toomer and the poet Countee Cullen were members of the black elite, they and other black writers combined European literary technique with African-American themes. The most popular and prolific of the black writers of the 1920s was the poet Langston Hughes, whose works showed a strong identification with the black working class. These writers found an audience largely due to the efforts of white patrons and black editors, such as Charles S. Johnson (1893–1956) at Opportunity (published by the Urban League) and Jessie Fauset (1886–1961) and Du Bois at The Crisis (published by the NAACP). Alain Locke (1886–1954), a Harvard graduate and a Rhodes scholar, was one of several black academics who promoted African-American and African culture. His work was later continued by Zora Neale Hurston (1901–60), a novelist who in 1935 published Mules and Men, an outstanding book of southern black folktales.

EUBIE BLAKE

As in literature, black activities in theater reflected a desire to display their cultural distinctiveness to the public. Several musical comedies produced in the 1920s by Eubie Blake (1883–1983) and Noble Sissle (1881–1975) allowed black performers to prove their talents. The actor Charles Gilpin (1878–1930) played more serious roles, including the title role in Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones. The actor Paul Robeson also performed in O’Neill’s plays, starred in William Shakespeare’s Othello, and later gained prominence as a singer of black spirituals and working-class folk songs.

African-American music was also deeply affected by the social currents of the 1920s. Previously confined to the South, jazz and blues began to be played in northern cities during World War I and soon became established in the rapidly growing northern black communities. Louis Armstrong went from New Orleans to Chicago in 1922 to play with King Oliver’s jazz band, and Jelly Roll Morton began arranging the previously spontaneous jazz pieces during the mid-1920s, preparing the way for big band leaders such as Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson.

DEPRESSION AND WAR

The cultural awakening of the 1920s lost momentum in the ‘30s as the worldwide economic depression diverted attention from cultural to economic matters.

Unemployment and poverty among blacks was high even before the stock-market crash of 1929, but the general downturn in the economy made it more feasible for blacks to join with whites in seeking social reforms. A small minority of blacks was drawn to the Communist party (see Communist Parties: the U.S.), which made special efforts to attract them and ran a black candidate for vice-president in 1932, 1936, and 1940.

The party’s black support remained small, however, and many black members, such as the writer Richard Wright, became disillusioned and left. More important was the involvement of blacks in labor unions, both all-black organizations such as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, led by A. Philip Randolph, and the industrial unions that joined to form the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO). Unions played an important role in forming the National Negro Congress, with Randolph as president, to promote black economic interests, but internal political disputes reduced its effectiveness.

Nonetheless, black workers became firmly established during the 1930s and ’40s in numerous industries. In part as a result of union involvement, the allegiance of black voters underwent a historic shift from the Republican party, which they had supported since Reconstruction, to the Democratic party. In the 1934 election, two years after Franklin D. Roosevelt won the presidency, for the first time most black voters supported Democratic candidates.

The New Deal

MARY McLEOD BETHUNE

Click On Picture for more information on her from the WONEM IN HISTORY Website.

Portrait of Mary McLeod Bethune by Carl Van Vechten. Published 1949.

Source: Carl Van Vechten, photographer, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (Reproduction Number LC-USZ62-42476DLC)

ROBERT C. WEAVER

Click on Picture to visit African-Americans in the Twentieth Century

Robert C. Weaver, Ph.D. (1907-) became the first African-American to serve in the President of the United States' Cabinet. He was Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under President Lyndon B. Johnson, starting January 3, 1966.

On the other hand, the Roosevelt administration did little to confront the special problems faced by blacks. New Deal programs did not help southern black farmers, who were hurt by the decline in agricultural prices and were not allowed to influence the Agricultural Adjustment Administration programs. Fearful of losing his southern white support, Roosevelt declined to back federal legislation against lynching. Blacks were often victims of discrimination on the part of federal relief programs, especially in the South. By excluding farmers and domestics, the Social Security Act of 1935 excluded 65 percent of all black workers. Similarly, the bulk of black workers were not covered by National Recovery Administration codes (see National Industrial Ricovery Act). Many federal housing programs also perpetuated patterns of residential segregation.

Today, we face a renewed effort as the forces of racism and retrogression in America are again on the rise. Many of the hard-earned civil rights gains of the past three decades are under assault.

Click on NAACP logo to go to their Home Page

Despite setbacks, however, a foundation was established during the depression for subsequent civil rights reforms through the alliance of blacks with white liberals. During the 1930s the NAACP led a vigorous legal battle against discrimination, concentrating on segregation in public education. In 1938, it gained an initial victory when the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the admission of a black man to the University of Missouri law school, because the state had failed to provide such facilities for blacks. The NAACP also played an important defense role in the Scottsboro Case, although its involvement came only after the Communist party had publicized the case.

World War II

The war against the Axis powers provided a great stimulus for changes in national racial policies, for it increased the need for black labor and heightened the sensitivity of whites to the dangers of racist ideas. On the eve of the war, a threatened march on Washington by blacks under the leadership of A. Philip Randolph persuaded Roosevelt to issue an executive order prohibiting racial discrimination in the defense industries and in government. Although the Committee on Fair Employment Practice, established under this order, had few enforcement powers, it encouraged a large-scale migration of blacks in search of jobs in defense plants. Between 1940 and 1950 this migration more than tripled the black population in the western states. Conflicts over housing and jobs developed in some cities between black and white workers, and a race riot occurred in Detroit in 1943, resulting in the deaths of 25 blacks and 9 whites before federal troops restored order.

Dorie Miller

In addition to the Navy Cross, Miller was entitled to the Purple Heart Medal; the American Defense Service Medal, Fleet Clasp; the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal; and the World War II Victory Medal.

While making gains in civilian life, blacks also sought to improve their status by military service. As in previous wars, blacks seeking to enter the armed forces faced considerable discrimination, although the War Department eventually approved the training of an unprecedented number of black officers and accepted blacks to serve as pilots and in medical and engineering units. Approximately half a million blacks served overseas in segregated units in the Pacific and Europe. Dorie Miller (1919–43) won the Navy Cross, the highest honor awarded to a black serviceman in the war, for his heroism at Pearl Harbor in 1941. As in civilian life, racial conflicts occurred on or near military posts and in occupied zones abroad; serious riots erupted at several camps, where black soldiers protested against poor conditions and racial discrimination. See also World War II.

Click on the Images above to go to "The Black Press: Soldiers without Swords"

Increased Understanding Among Whites

The desire of black Americans to win a victory over fascism abroad and racism at home was expressed in the so-called Double-V campaign, which also revealed an undercurrent of black discontent. Allied rhetoric about the fight for the “four freedoms” (of expression and worship; from want and fear) encouraged blacks to feel these ideals might be realized in the U.S. The growing acceptance among whites of racial equality was strengthened by the writings of numerous scholars, including the Swedish social scientist Gunnar Myrdal, author of An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944). Other scholarly and literary publications during the 1930s and ’40s increased understanding of the black experience, notably Richard Wright’s novel Native Son (1940); Black Metropolis (1945), an important sociological study, by St. Clair Drake (1911–90) and Horace Cayton (1903–70); and From Slavery to Freedom (1947), by the historian John Hope Franklin (1915– ). ks.

Click on the CORE logo to go the their Web Page

The nonviolent sit-ins conducted by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), formed in 1942, signaled a new willingness on the part of both white and black reformers to challenge racial segregation. White racial attitudes were affected by the entry of Jackie Robinson and other black athletes into baseball; even before, such men as the boxers Jack Johnson and Joe Louis and the track-and-field athlete Jesse Owens had notable impact on sports.

|  | |

| Charles R. Drew | Norbert Rillieux | George Washington Carver |

Less noticed were the achievements of black scientists, such as Charles R. Drew (1904–50), who developed a widely used system for storing blood plasma. The tradition of black scientific achievement, however, can be traced back to Benjamin Banneker (See Top of Page) in the 18th century; Norbert Rillieux (1806–94) who, in the 19th century, perfected a system for refining sugar; and George Washington Carver in the early 20th century.

THE STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM

After the war a period of rapid change in American race relations followed. As more blacks left the rural South for urban areas, the relative economic status of blacks improved. From 1948 to 1961, the proportion of blacks earning less than $3000 a year declined from 78 to 47 percent; at the same time, blacks earning more than $10,000 increased proportionally from less than 1 to 17 percent. (Nevertheless, the median income for whites in 1948 was higher than that of blacks in 1961.) Related to these economic changes was a rapid increase in the number of blacks attending college—from 124,000 in 1947 to 233,000 in 1961.

Early Gains

The existence of a growing affluent and educated black population in urban areas made possible major political gains. Black urban voters provided decisive support for liberal Democratic candidates, who in turn backed civil rights reforms. In 1954, three blacks—Augustus Hawkins (1907– ) of California, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (1908–72) of New York, and William L. Dawson (1886–1970) of Illinois—were elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, the largest number since Reconstruction.

A pattern of black influence on national politics was clearly established in 1948, when Harry Truman was elected president, even though he received only a minority of white votes. Truman had gained the support of blacks by issuing an executive order that eventually desegregated the armed forces and by supporting a pro–civil rights policy for the Democratic party over strong opposition from southern Dixiecrats. Although Truman’s actions had little immediate impact on blacks, they indicated responsiveness by the federal government. Vigorous political dissent among blacks was discouraged during the so-called McCarthy era (c. 1950–55), as black leaders, such as Du Bois and Robeson, came under government attack, but cold war anticommunism also provided leverage for blacks to demand that the U.S. live up to its democratic claims.

Poster Created by Sam Smith

Click the Poster above to go to the Official Brown v. Board of Education Site

The Brown Decision

Although neither President Dwight Eisenhower nor Congress was willing to take action on behalf of black civil rights during the first half of the 1950s, new presidential appointments to the U.S. Supreme Court prepared the way for a reversal of the separate-but-equal doctrine established by the Plessy decision. In 1954 a unanimous Court ruled, in Brown v. Board of Education, that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and the next year ordered public schools to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” Although southern white officials sought to obstruct implementation of the Brown decision, many southern blacks saw the ruling as a sign that the federal government might intervene on their behalf in other racial matters. Unwilling to wait for firm federal action, however, some began their own desegregation efforts. In 1957, black children defied white mobs in Little Rock, Ark., until Eisenhower sent troops to protect their right to attend an all-white high school. Nevertheless, ten years after the Brown decision, less than 2 percent of southern black children attended integrated schools. During the early 1960s, it was necessary to maintain federal troops and marshals on the University of Mississippi campus to ensure the right of a black student to attend classes.

Click Here to See Thurgood Marshall's Biography

Desegregation Struggle

The Brown decision also encouraged southern blacks to launch a sustained movement to integrate all public facilities. It began in Montgomery, Ala., in December 1955, when a black woman named Rosa L. Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus to a white man and was arrested. Led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., black residents reacted to the arrest by organizing a bus boycott that lasted more than a year, before a federal court declared Alabama’s bus segregation laws unconstitutional. King’s commitment to nonviolence garnered favorable press for his protests.

|  |

| Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. | Rosa Parks |

| Click Picture to See Civil Rights Museum | Click Picture to See BIOGRAPHY |

Although King remained the best-known black leader, protest activities soon moved beyond the control of any single individual or group. King’s supporters organized the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, but when black college students began widespread lunch counter sit-ins in February 1960, most of the young activists rejected leadership by SCLC and older civil rights groups, such as the NAACP or CORE. They formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which was often more militant than other civil rights groups.

Voter Registration

The CORE-initiated Freedom Rides of 1961, designed to end segregation in facilities dependent on interstate commerce, demonstrated the ability of civil rights protesters to force federal intervention in the South. They brought many young activists into Mississippi, where white officials firmly resisted any concessions to the civil rights movement. Black civil rights leaders in Mississippi, who had long struggled for gains with the help of the NAACP, encouraged young civil rights workers affiliated with the SNCC to concentrate their efforts on achieving voting rights. By 1962 Robert Moses (1935– ), a Harvard-educated schoolteacher, had brought together a staff of organizers who worked closely with local residents seeking to register as voters. White resistance, however, remained intense. In 1964, after the murder of three of the organizers, a major national effort led to the unsuccessful challenge by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic party, led by Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–77), to unseat the all-white Mississippi delegation at the Democratic National Convention.

Click Here to See Freedom Ride Exhibit

Civil Rights Museum

Although the voting-rights movement in Mississippi made slow progress, civil rights protests in southern urban centers achieved important gains. Massive demonstrations were held in Albany, Ga., during 1961 and 1962, and the following year more than a million demonstrators kept up the pressure in numerous cities. This wave of protests reached a peak during the spring of 1963, when federal troops were sent into Birmingham, Ala., to quell racial violence. President John F. Kennedy reacted to the widespread demonstrations by introducing civil rights legislation designed to end segregation in public facilities. On Aug. 28, 1963, more than 200,000 protesters gathered in Washington, D.C., for a peaceful demonstration, calling for congressional action in civil rights and employment legislation. The civil rights bill remained deadlocked in Congress until 1964, however, when it was passed in the aftermath of the assassination of President Kennedy. In 1965 another series of protests in Selma, Ala., prompted President Lyndon B. Johnson to introduce new voting-rights legislation, which was passed that summer and had a dramatic impact on black voter registration; in Mississippi, the percentage of blacks registered to vote increased from 7 percent in 1964 to 59 percent in 1968.

Click Here To Go To Brother Malcolm Dot Com

© 1999-2004 TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY BOOKS

Black Pride

The years of civil rights activism in the South led to an upsurge in racial pride and militancy among blacks throughout the nation. In 1966 the SNCC announced that the goal of the black movement was no longer Civil Rights but “Black Power,” which could be achieved only when black people developed a more positive image of themselves. Such sentiments coincided with a trend toward black militancy in northern urban centers spearheaded by Black Muslims. Although the best-known advocate of black nationalism, Malcolm X, had attracted only modest support at the time of his assassination in 1965, his ideas became increasingly popular after his death. His calls for armed self-defense reflected widespread anger among urban blacks that burst forth in extensive racial violence in Los Angeles in August 1965. During the following three years, nearly every major urban center in the U.S. experienced similar black rebellions. The Kerner Commission, set up by President Johnson and headed by Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner (1908–76), reported in 1968 that the “nation is moving toward two societies, one white, one black—separate and unequal.” New militant organizations, such as the Black Panther party, sought to provide leadership for discontented urban blacks. The outspoken radicalism of many black leaders resulted in considerable federal repression, and by the late 1960s most of the black militant groups had been weakened by police raids as well as internal dissension. Before his assassination in 1968, even Martin Luther King, Jr., became a target for government surveillance and harassment, as he responded to the new mood of militancy with forceful attacks on U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and with calls for economic reforms.

MUHAMMAD ALI

Blacks attending college launched a movement to introduce black studies into the curriculum, which resulted in better knowledge of the African-American experience. A new spirit of racial assertion was especially evident in sports; in the 1960s black athletes brought into college and professional sports a distinctive, individualistic, and spontaneous style of play, often over the objections of white coaches and sportswriters. For example, the heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali’s refusal to be inducted into the army temporarily cost him his world championship but also made him a hero to many blacks.

Click Here to See Thurgood Marshall's Biography

THE LATE 20TH CENTURY

The declining effectiveness of the radicals gave more moderate black leaders a chance to reassert themselves, although they, too, often adopted elements of the black consciousness rhetoric. Thus, during the 1970s public attention was increasingly directed toward leaders reflecting a variety of strategies that did not threaten the American social order. Thurgood Marshall, the first black appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court, symbolized the possibilities for working within the political system. The executive director of the Urban League, Whitney M. Young, Jr., transformed his organization into an important social welfare institution.

Click Here to see Shirley Chisholm's biography

The formation of the Congressional Black Caucus provided black U.S. representatives with the means to determine priorities of racial reform. The National Black Political Convention, held in 1972 in Gary, Ind., was attended by 8000 delegates and marked an effort to broaden black participation in discussions of political alternatives. In that year Representative Shirley Chisholm, a Democrat from New York, became the first black woman to run (albeit unsuccessfully) for the presidential nomination of a major party.

Blacks in the Arts

The upsurge of activism in the 1960s significantly affected black social and cultural life. As in the 1920s, black people manifested growing interest in African and African-American history and closer identification with the disinctive aspects of their culture. The writers Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin and the playwright Lorraine Hansberry (1930–65) had suggested the new direction even before the ’60s, but the dramatist and poet Imamu Amiri Baraka (originally named LeRoi Jones; 1934– ) set the tone for the late ’60s with his emotional condemnations of white values.

The cultural revival continued, although not always within the confines of the earlier militant mood. Writers such as Alex Haley, Paule Marshall (1929– ), the 1993 Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Gloria Naylor (1950– ) committed themselves to describing and analyzing the black experience. Among the playwrights of that period were Pulitzer Prize winners Charles Fuller (1939– ), who received the prize in 1982 for A Soldier’s Play (1981), and August Wilson, who in 1987 received the prize for Fences (1986) and The Piano Lesson (1990). Poets also contributed their voices, among them Gwendolyn Brooks—in her To Disembark (1981) she calls for a “disembarking” from oppressive white cultural patterns—Maya Angelou, Nikki Giovanni (1945– ), and poet-playwright Ntozake Shange (1948– ). The poet, playwright, and novelist Rita Frances Dove (1952– ) was appointed U.S. poet laureate in 1993, the first black woman to hold that honor. In other media there have been the world-renowned operatic soprano Leontyne Price; dancer-choreographer Alvin Ailey, whose works expressed the black heritage; filmmakers such as Gordon Parks (1912– ), Melvin Van Peebles (1932– ), and Spike Lee; and painters, working in different styles, among them the poetic Romare Bearden (1914–88), the realist Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), and Benny Andrews (1930– ). Andrews, whose paintings are social commentary in allegorical form, was one of the organizers of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, which in 1969 protested against the inadequate representation of blacks in American art. From rhythm and blues in the 1950s to hip-hop in the ’90s, black performers have had a major influence on the development of popular music in the U.S. and throughout the world. See also American Art and Architecture; American Literature; African-American Music; Rock Music.

COLIN POWELL

CLICK HERE TO SEE BIOGRAPHY

Political Gains

Despite setbacks, the black activism of the 1960s produced some lasting political gains. As black residents of central-city areas became sizable minorities—and, sometimes, majorities—of the electorate, black candidates were able to win elections. During the 1970s black mayors were elected in Cleveland, Ohio; Gary, Ind.; Newark, N.J.; Washington, D.C.; Atlanta, Ga.; New Orleans, La.; Los Angeles; and other U.S. cities. The 1980s brought the election of black mayors in Chicago, Philadelphia, New York City, and other cities throughout the country; the total number of black mayors was 318 in late 1990, the same year that Democrat L. Douglas Wilder (1931– ) took office as governor of Virginia. Overall, the number of black elected officials in the U.S. rose from about 300 in 1965 to some 7480 (including 26 members of Congress) in late 1990. Two years later, the first black woman senator, Carol E. Moseley-Braun (1947– ), was elected from the state of Illinois. Gen. Colin L. Powell became the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1989, played an important role in the Persian Gulf War (1991), and remained one of the nation’s best known and most admired public figures throughout the 1990s into the 2000s, becoming Secretary Of State in George W. Bush’s administration in 2000.

Click Here to See Gen. Powell @ Academy Of Achievement

RICE, POWELL HAVE SEPARATE STYLES OF DIPLOMACY

WASHINGTON — Considering the dismal state of transatlantic relations, Colin L. Powell's farewell trip to Europe as secretary of State last month (December 2004) drew an impressive outpouring of personal affection as he readied to convey his office to Condoleezza Rice.

By Tyler Marshall LA Times Staff Writer.

General Powell did leave his post standing up for what he thought was right concerning the war in Iraq. He warned the President that if we went to war there we would never be able to leave. (He was right and the current administration will never admit that they were wrong concerning this. Therefore they have the perfect scapegoat in Condoleezza Rice not only will she will not try bring us out of this war but as time goes on she will be blamed for everything that will go wrong in this war and the situation in Israel (And You Can bet your Last Dollar it will). The point that the LA Times made saying that "Rice, Powell Have Separate Styles of Diplomacy" is a very serious understatement.

Click Here to go to the Secretary of State Webpage

UPDATED Measage July 30th 2008 By Vincent L. Scott

If someone had told me that this would be an ongoing narrative; I may not have wanted to do this: But, I did promise that I would reevaluate my thoughts concerning Ms. Rice, and surprisingly enough we have our first major party presidental nomination with Mr. Barack Obama so I want to give my views on both.

Concerning Ms. Rice.

I disagreed with the issues that she stood for mainly for not getting either Bush administrations to get our troops out of Iraq.

I did not consider that, then, but now, I know, that this is a person that has interests in an oil company(As she was the formal president of an oil company) and her ties to the Bush people shows that she even though she is black, she is only interested in what would be in her best interest.

I mean when I first started down to write this, I was going to commend her for standing her ground even though I thought she was wrong. But as I thought about her background, now I can only think that she and the Bush Administrations were only looking out for their own interests and not of that of you or me. Sorry Ms. Rice, but I cannot commend you when I am so sure that you do not care one way or the other. Yes, you did a fine Job as secretary of state but for whom were you working for? I sure was not me or the American People: You did a fine job for yourself, and those oil companies you have investments in.

Concerning Mr. Barack Obama.

Well, what can I say??? This is a great step forward as far as Black history is concerned. But we have to remember that (White) America still thinks that the only job a black person is qualified for is the cotton picking job.

And to prove this point, people (yes, even black people) will bend over backwards to give the preception that their is something "wrong" with black people. let's take the July 21, 2008 issue of the New Yorker for example(seen below).

Aides to Barack Obama are blasting a New Yorker magazine cover that depicts “President Obama” in the Oval Office, wearing a Muslim-style outfit and doing a fist-bump with his wife, Michelle, who is dressed in camouflage with an automatic rifle slung over her back. A picture of Usama bin Laden hangs above the mantel of the fireplace, which has an American flag burning in it.

The July 21 cover, titled “The Politics of Fear,” is intended to be a parody, an attempt to show how “scare tactics and misinformation” are being used to try to derail Barack Obama’s campaign, says cover artist Barry Blitt.

Well, the way I see it, the road to hell is paved with "good intentions" and what is said to be a "parody" actually will be seen as the truth. (As far as a lot of people will look at it) A recent poll has indicated that Obama will not get the middle class working white vote.

This is a sad thing to say, but the man will not be judged by the content of his character; but content of his skin color.

Well this will be a good spot to put the least we forget presentation from the New York Public Library. This is a very good primer concerning the continuing fight against slavery. Please, CLICK HERE to see this very good presentation.

The gains mentioned above are counterbalanced by less favorable trends. An upsurge of black voter registration, stimulated in part by the 1984 and 1988 Democratic presidential primary campaigns of Jesse Jackson, a Baptist minister and social activist, came to a halt in 1988. Since that time, black voter registration and turnout have declined. The 1994 congressional election, in which only an estimated 37 percent of eligible black voters cast ballots, resulted in the loss of the Democratic party’s majority in the House of Representatives and a consequent decline in influence by the Congressional Black Caucus. Moseley-Braun’s reelection defeat in 1998 meant that, as the 1990s ended, the U.S. had not a single African-American senator or state governor. There were 39 black members of the House, of whom all but one were Democrats.

Click Here to go to

Operation PUSH and Rainbow Bureaus

Income and Employment

The economic status of African-Americans was also a mixture of highly visible improvements and persistent problems. Throughout the 1970s and early ’80s, blacks made steady gains in academic achievements, greatly increasing the size of the black middle class. In the late ’80s, it became increasingly difficult to sustain earlier gains, and in some instances small reverses occurred. In 1980, 9.2 percent of all blacks were enrolled in college. By 1990, only 8.9 percent were enrolled. While the median black family income rose to more than $19,700 a year and about 29.6 percent had annual incomes higher than $35,000, black family income remained at less than three-fifths the median family income of whites. In ironic contrast to the economic dynamics that first brought Africans to North America, some of the most vital U.S. industries began to use foreign workers—usually not unionized, and unprotected by minimum wage laws—instead of unskilled urban black workers. Unable to obtain the industrial and domestic-service jobs that had attracted earlier generations of blacks to urban centers, ghetto residents were increasingly mired in economically depressed urban areas that offered few opportunities for upward or outward mobility. The long-term movement of blacks from agricultural and domestic-service jobs to urban industrial occupations—which some think did more for 20th-century black economic progress than all the civil rights laws and affirmative action programs—had become a spent force.

U.S. economic expansion in the mid- and late 1990s brought a corresponding improvement in the economic position of black Americans. Black college enrollments began to rise again, and by the late 1990s median black family income had increased to about $25,350, or approximately 62 percent of the median family income of whites. More than one of every three black families had an annual income greater than $35,000. On the other hand, about the same proportion of black families were still earning less than $15,000 a year, and unemployment rates among young black men and women were more than double those of whites. Black students also lagged behind whites in access to computers and the Internet, a significant impediment in competing for jobs.

Cultural Dichotomy

The common historical experiences and cultural values that made possible previous black movements for racial advancement remain a source of creative energy and cultural innovation. Many blacks have become enmeshed in middle-class society, with its pervasive institutions that supplant or absorb the distinctive aspects of African-American culture. Nevertheless, poverty and alienation continue to shield segments of the black populace from complete cultural absorption. Du Bois’s plea in Souls of Black Folk (1903) that blacks maintain their cultural heritage was combined with a realization that they have a “double consciousness.” He wrote, “One ever feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

From a series of articles from Funk & Wagnalls® New Encyclopedia. © 2005 World Almanac Education Group, A WRC Media Company

View My Guestbook

Sign My Guestbook