The stories of Jacob, Samson, Jonah, and Ruth may seem like they are too different to be considered in the same light. However, the stories carry essentially the same meaning. All deal with a person’s fall from grace, and the person’s struggles through the “real” world. These eventually lead to the reestablishment of the main character of the story as a fully-realized individual with a proper relationship to the divine.

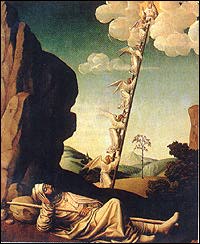

In the story of Jacob, he begins in a state of Paradise, protected by the divine in the forms of his parents, Isaac and Rebekah. However, he makes a claim to the divine in what will be a premature fashion that will lead to his fall from grace. He deceitfully takes his father’s blessing, and is now entrusted to become a fully-realized man, a patriarch like his father. Out in the wilderness, “he came to a certain place and stayed there for the night, because the sun had set. Taking one of the stones of the place, he put it under his head and lay down in that place” (NRSV, Gen 28.11). Had he not been fated for greater things, Jacob could have lived and died ignorant of his divine heritage, asleep in the metaphorical darkness. However, he has a dream in which he sees a ladder traversed by angels connecting heaven and earth. The meaning of the dream is that he sees the possibility of fully realizing his essential nature. The earth is man, and the sky is the divine. He sees that it is possible to live a life fully connected to God. He awakens from the sleep that dominated his life, and sets out to work for his relative Laban, yet another representation of God as an older relative (or, perhaps, Laban is a spiritual teacher). He works many years for Laban as a seeker of truth and higher understanding. The truth is, though, that he has been working for himself all along: He has married his love Rachel, though not before being tricked into marrying the older sister Leah. His “come-uppance” in marrying the older sister Leah is the divine reestablishment of justice in the face of Jacob’s pride in taking his older brother Esau’s inheritance. He comes out winning from his years of work under Laban, though. He has many children, and obtains many sheep and goats from Laban. After fleeing from his life as a spiritual seeker under Laban, he is closer than ever to fully realizing his divinely-appropriate role as a patriarch in the line of the covenant. Out in the wilderness, he and his family celebrate with Laban “all night,” as opposed to Jacob’s sleeping through the night as at the time he had his dream of the ladder connecting heaven and earth (Gen 31.54). In a struggle with a mysterious angel in the night, his “hip-socket” is injured (Gen 32.25). The notes to the NSRV mention that the text hints that his reproductive organ may have been injured, which also makes sense as Benjamin, his last son, has already been conceived. The injury to the reproductive organ is appropriate, as it signifies the end to Jacob’s struggles in and submission to the ordinary world, which is a sexual world of competition, desire, and unfulfilled realization. It is now that Jacob can reconcile with his worldly half, his twin brother, the hunter Esau, and live as a fully-realized human being.

The story of Samson, if one ignores what are probably later additions of Delilah and Samson’s death, is also about a human being realizing his full, divine potential. He begins in a similar state of grace to Jacob’s, as a young man protected by his parents. However, he has worldly ambitions that will eventually become refined into divine ambitions and subsequent self-realization. He wishes to marry a Philistine woman. Though his parents disapprove of the marriage outside his faith, “his father and mother did not know that this was from the LORD; for he was seeking a pretext to act against the Philistines. At that time the Philistines had dominion over Israel” (Judges 14.4). The Philistines are representative of the world, and they are similar to Laban in that they are an oppressive force on the hero, which is not the ‘way things should be.’ On the way to meet the woman, Samson tears apart a lion and later eats honey that comes from bees living in its belly. The NSRV notes how “honey was regarded as having the potential to enlighten and to give courage” (NSRV Judges 14.8-9 notes). This early enlightenment is reminiscent of the dream of Jacob and the ladder. Both are events that happen early to the hero in his journeys and which give him the strength to continue on to the rightful end. After his marriage, Samson shows his submission to the sexual, ordinary world when he gives in to his wife’s nagging and tells her the answer to his riddle, which results in his defeat by the Philistines. His pride and attachment to worldly superiority result in a worsened situation: His rage at ‘not being the best’ at a riddle game result in his marching back to his father’s house and inadvertently losing his wife. It does not matter to his angry spirit that he isn’t the one who provides, as is obvious in his acquiring of the wager-garments only after the “spirit of the Lord rushed on him” and he killed 30 people to obtain what he needed (Judges 14.19). In his ongoing struggle with the world, he burns the Philistine’s fields, and they burn Samson’s wife and her father because he married her to another and enraged Samson. Like Jacob injuring his hip-socket at the hands of the angel, Samson’s ties to the ordinary sexual world and its mentality are cut off with the death of his wife. He is now free to wage all-out war on the Philistines who unlawfully dominate the land. Bound by his fellow Israelites, he is turned over to the Philistines to a ‘death,’ which is reminiscent of Jacob’s old identity dying when he is renamed/reborn as Israel. He breaks his bonds and kills the usurpers of the land with a donkey’s jawbone. The problems of the world are like weeds facing a sickle when one is willing to die to one’s own greed and sexual ambitions and do what is just. However, he is ready to reclaim his mature, self-realized role as a judge and leader to his people only after tasting the reviving water given to him by God in an act of final communion, when Samson rudely (as always) demands refreshment, which pours from a rock. This is a show, perhaps, of the miraculous ease with which God provides for the well-being of the enlightened person, and refreshes their spirit. The stories of Delilah and Samson's death are probably expanded versions of the concepts brought out in the original story when Samson gave in to his nagging wife and when Samson submitted to a metaphorical death by being bound and then killing the Philistines.

The story of Jonah is yet another story of the fully-realized person. It begins with a calling on a person to realize his full potential, which is intimately tied with serving others and not oneself: “Now the word of the LORD came to Jonah son of Amittai, saying ‘Go at once to Nineveh, that great city, and cry out against it; for their wickedness has come up before me’” (Jonah 1.1-2). The ordinary person is called on to serve God’s purpose, rather than his or her own. However, this prophet-to-be runs away from his duties and lives in an immature world of delusion. He sleeps in the hold of a ship bound in the opposite direction of where God wants him to go. Like Jacob waking up after hearing the word of God, so Jonah is roused from forgetfulness of the divine through a great storm sent by the Lord. He experiences this early enlightenment only to be swallowed up by the problem of the world, in the form of a gigantic fish, so akin to the Philistines as a mass and Laban as an oppressor. He approaches Sheol, and is ‘reborn’ as a man willing to obey God’s will. After being vomited out by the fish, he does God’s will and leads the people of Nineveh to repentance. They fast, wear sack-cloth, and sit in ashes, which are all signs of dying to oneself and one’s own delusions and living in the Lord. Like Samson leading the Israelites as judge for twenty years after slaying the thousand Philistines, so Jonah has become a teacher and shining example to other people in his submission to God. In later events, “God appoints a bush to save Jonah and then destroys it to bring the prophet to his senses” (NSRV Jonah 4.6-8 notes). This is a simplified parallel to the overall story of Jonah. The bush is the world which sustains Jonah and his illusions of himself. Jonah does not create the world, or destroy it. However, he is ignorant enough to be angry when he sees it destroyed, or the presence of ‘evil’ and (his) suffering in the world. The worm- a monster like the large fish- is designed to remind Jonah of his place, and God’s, in the world. This event enlightens Jonah as to the divinely-established presence of so much unfairness in the world, symbolized by the Nineveh Assyrians, and their brutal, imperialistic ways, which were quite familiar to the book’s original audience. It is a reminder that the unfaithful people of Nineveh- now a symbol of all people who are ‘asleep’- are deserving of our patience and selfless efforts to awaken them in the same way God rudely awakened Jonah from his delusions.

The book of Ruth has as its main character the Moabite woman Ruth, paired with Naomi. Naomi and Ruth begin the story in Paradise, when they have husbands and things are ‘right.’ However, their fall from grace is the death of their husbands. In a strange land, with great poverty in sight, Naomi and her daughter-in-law Ruth can only find divine completion in the land promised to Naomi’s ancestors. “So she (Naomi) set out from the place where she had been living, she and her two daughters-in-law, and they went on their way to go back to the land of Judah” (Ruth 1.7). Like Samson on his journey to his wedding, and Jacob on his journey to Laban, the journey is the worldly condition of separation from and search for God, which will ultimately lead to a return to a proper state. As a foil to Ruth, Orpah chooses selfishness and leaves Naomi to look for a new husband. She is to represent those who refuse to awaken, distracted by self-centered concerns. Like Jacob at work for Laban during twenty years, Ruth spends an entire harvesting season gleaning from the fields of Boaz. She receives more grain from the fields of Boaz than an ordinary gleaner would, in the same way that Jacob walks out of his period of growth under Laban with many sheep and goats. The benefits granted by God to the spiritual seeker are greater than one would expect for someone who isn’t devoted to the selfish cause. A relative of Naomi, Boaz refers to Ruth as “my daughter,” in the same manner as Naomi refers to her (Ruth 2.2, 2.8). This could lead to speculation of Naomi and Boaz, as Ruth’s older protectors, to be aspects of God. Loving God in the feminine form guides Ruth through life properly as a result of Ruth’s efforts to foster this divinity within her by protecting and nourishing her with hard spiritual work in the worldly fields. (Or, like Laban, Naomi could be a spiritual guide or teacher.) She is led to reunion with the divine in the form of marriage to Boaz. Ruth also shows a rejection of the ordinary, selfish, sexual mentality when she asks for marriage from Boaz and he praises her for not going after young men. Instead of choosing a young husband for herself, as seemed only natural at the start of the story when Naomi advised her to leave her, Ruth has chosen to uphold chesed, or the love of God, symbolized here by the family and marriage laws. A new day rises on the family, “as a son has been born to Naomi” (Ruth 4.17).

In summary, at least some of the stories of the Hebrew Bible convey a deeper message about what it is to be a self-realized, mature person. Whether referred to as a patriarch, a prophet, a judge, or a woman with a complete family, all the aforementioned stories are about people in their highest state. This state is the one that is pleasant to the Lord. May we all grow in wisdom.

The HarperCollins Study Bible: New Revised Standard Version. HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. New York, NY. 1993.

Some additional notes:

Patterns like the aforementioned ones can be found in religious stories over and over again. The story of Job details a rich man's fall from grace (the loss of his wealth and children), his struggles to understand his state of suffering (long, complex discussions with his friends), and a proper reestablishment of his position, when he has been cleared of delusions by God and becomes a wealthy man again. I remember noting some particularly deep points in God's speech, which I remember thinking said things along the lines of: "There's a deeper understanding that transcends your suffering and questioning, and God created this vast, suffering situation. The monstrosities are part of My Creation, too." In the book of Daniel, there's a chapter that details Nebuchadnezzar's fall from grace at God's hand, his living like an animal, with long nails, and grass for food (our miserable state), and God setting him back up again after the period of suffering, when his wealth is doubled.Moving on to other cultures, the stories of Parvati and Shiva from India are similar. In one story, Parvati was insulted for her dark skin by her husband Shiva. Living in a world where her ego dominates and this leads to suffering (interestingly tied in to her husband/sexuality), she went into the forest and lived as an ascetic. Her austerities impressed Brahma, who transformed her into Gauri, a creature of golden skin. What is wonderful about this story is that all the characters are Hindu gods from the beginning. In a different story, Shiva and Parvati switch roles. Parvati went up to her husband, and covered his eyes from behind. Now living in a state of ignorance, Shiva's only recourse was the awakening of the transcendent third eye, which opened up on his forehead above Parvati's hands.

In a Native American story from some tribe I don't remember, Hare's brother was killed by his enemies (by the world...God...who knows). Now in a fallen state, Hare went in search of his enemies in a great quest. When he found them, he forced them to tell him the secrets of medicine (spiritual power). He resurrected his brother (things were set right again), and that is how the people of the world learned medicine.

In Scandinavian myth, there is the story of the young god Freyr. Like Jacob wrongfully claiming his older brother's inheritance, Freyr sat on the chief god Odin's throne when no one was around, which was forbidden. From it, the nine worlds could be seen. He beheld a beautiful woman in the land of the giants, enemies of the gods. She was the frost giantess Gerd, and when she opened a window in her hall, her arms shone brightly and the whole world was illuminated. Like Jonah being roused by the divinely-sent storm, Jacob by the voice of God and the vision in the night, Samson by the honey, and so on, Freyr experienced early enlightenment, a shocking revelation of his need for completion. He desired Gerd immensely, and he became despondent. He was miserable in his state, and his fellow gods noticed his lack of appetite and sense of alienation. But the divine plan does not wish us to remain in this state. His caring father Njord sent the servant Skirnir to fix what was wrong. A questing, heroic alter-ego to Freyr, Skirnir the servant, or reason, is selected to save the essential self, or Freyr. After planning with Freyr, Skirnir travelled to the hall that Gerd lived in, armed with Freyr's horse and sword. He was received by Gerd, and tried to woo her unsuccessfully several times for Freyr. It seems like the spiritual seeker got fed up with his failures, so he threatened to have the sword magically kill her in some versions, or that he would curse her, in others. Perhaps what is being represented is the person's gaining of power in the eventual rejection of the spiritual search, or quest for Gerd, like when Jacob fled Laban. Gerd gave in to Skirnir's proposal that she marry Freyr, and when they met nine days later, some sources say, the warmth of his love melted her icy heart. Skirnir got to keep Freyr's horse and sword, as the completed person has no need to continue questing, or so I believe. Retellings of this story emphasize that Freyr's loss of his magical sword would contribute to his guaranteed death at Ragnarok, or the Scandinavian end of the world. However, Ragnarok seems to be a story with the same meaning, although a diferent type of story, as all the aforementioned ones. This may symbolize a cyclic reliving of these stories during a single individual's lifetime, with Ragnarok being the end-game wherein the person (the entire world) is purified to the utmost degree with the death and destruction of all gods, people, and land, and the beginning of a new world order with new gods and people. Or, perhaps, the wedding story of Freyr and the tale of Ragnarok are the exact same story, with the former one emphasizing the sense of completion to be attained, and the latter story emphasizing the radical nature of the death of the delusive self-identity.

There is a similar parallel in the story of Freyja, twin sister of Freyr. Her husband Od left her, and in this fallen state, she cried golden tears. Our beauty and magic seem to flow forth not from our original state of contentment, or Paradise when we were married, but from the suffering that comes of being broken. After her husband left, the goddess became very promiscuous, or a symbol of the searcher for completion. There is a story that she debased herself in the worst fashion when she lusted for the Brisingamen, or a precious necklace made by four dwarves. She married and slept with each for a day and night in order to receive the precious necklace. In a version of the story I am unable to find again, this is her fall from grace, when her husband leaves with the necklace after he is told of her infidelity by Loki, the trickster "hand-of-god." In different stories, she is either made to search for her husband, or is given the precious Brising necklace by a questing Heimdall, one of the gods, or returned the necklace by Odin (who may have originally been her husband Od himself, as Freyja has also been potentially linked to Frigg, the queen of the gods and wife of Odin, in older times when they may have been the same goddess) only on condition that she change from a goddess of love and fertility to a war goddess who must oversee the battlefields and claim half the souls of the brave warriors and take them to her hall, while Odin gets the other half. This, however, is not really a punishment. She has now become a spiritual guide and teacher, and oversees the battles and deaths of the spiritual seekers under her tutelage, the brave warriors of the worldly fields.

Also in Scandinavian myth, Odin searched far and wide for wisdom, but was unable to go further because there was hidden wisdom that only the dead held. So he hung himself from the world tree, died, learned the wisdom of the dead, and resurrected himself. Perhaps you could see a similar pattern in the story of Christ's death and resurrection. Paramahansa Yogananda hints that Christ's death may be the death of the flesh and seeing oneself as spirit. This view need not be discouraging to Christians, though. The doctrine of Christ's unique divine status and importance in the role of sacrificial savior can coexist with the concept of the death and resurrection being a journey one must emulate. Or, perhaps, one can accept one possibility as true, the other as false, or neither as true. (This applies to beliefs from all religions. You really can't prove them either way.) Anyway, don't worry about it. Confusing ambiguities are only reflections of the ultimate reality.