|

www.angelfire.com/dragon/letstry

cwave04 at yahoo dot com |

|

|

|

Continuous time finite automata

So far our discussion has been revolving around finite automata from

the

viewpoint of software. But finite automata are no less (arguably even

more) important in the field of hardware, and softwares that

directly

interact with hardware. A robot, for example, is armed with

finite automata from top to toe.

In this section we shall take a look at how finite automata are used in

hardware. These automata are special cases of the automata we have

discussed, and we shall call these continuous time finite

automata.

So far our finite automata were all working in "discrete time". This means that the inputs came one by one, and after each input the DFA produced the output, updated the state,

and then waited for the next input. If we assume that the inputs arrive every second then it is like a short burst of activity at every tick of the second-hand followed by no activity until the next tick.

In the world of hardware, however, time is continuous. Inputs and outputs are voltages through wires and every wire has some voltage or other all the time.

Is it possible to design a DFA that takes continuous inputs and produces continuous outputs?

The DFAs we have discussed so far do not appear to be applicable here, right? Well, appearances are deceptive, as we shall soon see. But first a little example to clarify the difference between discrete time and continuous time.

A little silly game

Here is a small roleplaying adventure game for you.

The storyline is like this: You are a gunman figting against a tank.

Your gun is strong enough for the encounter, but

the tank is behind a moving shield-like armour that makes it

immune to

gunfire. However, you also have a disarmer which deactivates the

armour. After

you have disarmed the tanker

you can try to kill it with your gun. You will need two firings

for that, as the first bullet will only injure the tank, but not

kill it. If you do not succeed in killing the tnk within three

steps (i.e., three button clicks) then the tank will kill

you.

In a textbased version the game looks like this:

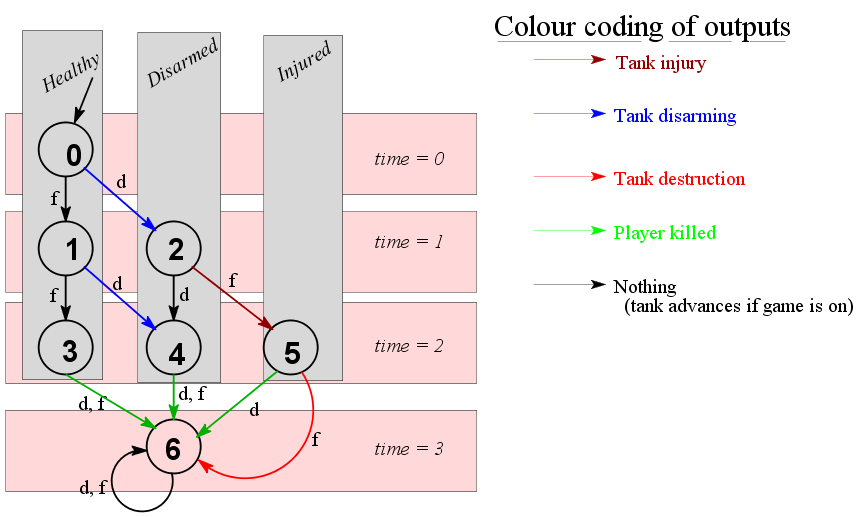

Here is the transition diagram. We have 7 states (numbered 0 to

6). initial state. State 6 is the final state (where either the

player or the tank is destroyed). All the other states record two

info: the elapsed time and the condition of the tank (healthy,

disarmed or injured).

The rectangles in the background help you see this clearly. The

arrows are labelled with only the inputs (d for disarm, f for

fire). The outputs are shown using the colour of the

arrows.

Does this game really

create the same feeling as you would feel if you faced

a tank charging straight at you? No! Here it is obvious that

you are merely playing a game against the tank where the MOVES

ALTERNATE. Howsoever powerful the tank might be, it has to

wait patiently until you make your move. That is to say time is

discrete here. It is marked by ticks that correspond to

your pressing a button. Nothing can happen between

two ticks.

A real enemy, however, will not wait for you to take action. It

will move at its own pace unless you manage to thwart its attack

in time. In other words, in real world time is continuous.

To see why our code failed to have this realistic behavior

consider how you would implement the automton in C. At each state

we emit some particular message on the screen, and then we

wait for your response. It is this waiting

that blocks everything else until you click on a button.

We refer to this type of behavior as blocking.

Here is a graphics version of the same game. You must first click

the "START" button to start the game.

This game is much closer to reality. The tank seems to have

a life of its own. Even if we do not actively do anything the

tank now continues to approach, i.e., the output is

produced in continuous time. However, at the same time it is

also continuously listening for any input from the user, since

the instant we click "DISARM" the armour vanishes.

How is the code managing both these tasks

simultaneously? What we are doing here is called

multitasking, and involves a little cheating.

Actually, behind the scene we are still using discrete time, but

the ticks are so closely spaced (say once every millisecond) that

it looks like continuous time. At these ticks we are not waiting

for any event to happen. We are merely scanning the present

conditions of the inputs. For example, the computer may scan

a button one million times between a button press and its

subsequent release. Viewed in this micro-time-frame a button is a

source of input that can be in either "pressed" or "released"

condition.

Note that we have to keep track of three sources of inputs: the

two buttons

and the timer (that controls the tank). The input a each tick

consists of the current status of these. Each of the buttons can

be either pressed or released. The timer can be either running or

timed out (when the tank has killed you).

So at the level of milliseconds there are actually 6 inputs:

- Timer on, "Disarm" released, "Fire" released:

(abbrev: tdf),

- Timer on, "Disarm" released, "Fire" pressed:

(abbrev: tdF),

- Timer on, "Disarm" pressed, "Fire" released:

(abbrev: tDf),

- Timer out, "Disarm" released, "Fire" released:

(abbrev: Tdf),

- Timer out, "Disarm" released, "Fire" pressed:

(abbrev: TdF),

- Timer out, "Disarm" pressed, "Fire" released:

(abbrev: TDf),

Since you have only one mouse pointer, you cannot press both the

buttons simultaneously! So there is no DF case. Also, because of

the same reason the input dF and the input Df cannot occur side

by side.

You'll need some space of time to take the mouse pointer

from one button to the other, thus inserting the input tdf or Tdf

in-between.

We still have basically the same set of outputs, but with

one important difference. In the discrete case the inputs were

events that we waited for. In the continuous case the inputs are

conditions of input sources that we merely observe. In the

discrete case the outputs

were events that we caused to happen (like "injure the

tank"). In the continuous case the outputs will be the possible

conditions

that can prevail (like "the tank is injured").

- Tank disarmed

- Tank injured

- Tank destroyed

- Player killed

- Tank healthy

So we need a finite automaton to produce these 5 outputs from the

6 inputs above. Clearly, the discrete time automaton mentioned

earlier cannot do the job, since its input set was of size 2,

while our input set is of size 6.

We shall learn later how to design a finite automaton in this

situation.

For now here is a finite automaton that

answers our need.

We have used some abbreviations here: T** stands for all inputs

starting with a T (i.e., Tdf, TdF, TDf). Similarly, ***

denotes the set of all possible inputs.

Here 0 is the initial state. By the way, it can be shown that we

can never achieve our goal here with a DFA with fewer

states.

The following interactive animation may help you to understand

the workings of the automaton. First click START. Then click the

the other two buttons. But in order to see the details, hold a

button for some time before releasing it. (This does not apply to

the START button, which may be clicked in the ordinary way.)

You'll see that

pressing a button triggers some action while releasing it may

trigger a different action.

This DFA is an example of what we call a continuous time

DFA.

If you play with the above animation for some time you will

notice that when you are not changing the input (e.g., while

holding a button down) the little

red blob keeps on circling around a loop at the current state.

This is the characterising feature of a continuous time

DFA. Before we discuss why this is important let us precisely

write down the definition of a continuous time DFA.

Defn: Suppose that you have a DFA with output function

f and next state function g. This DFA will be called a

continuous time DFA if it satisfies two conditions:

- If for any two states s,t and any input

in we have t = g(s,in), then we must also have

g(t,in) = t.

- If for any two states s,t and any input

in we have t = g(s,in), then we must also have f(t,in)

= f(s,in).

The conditions can be more readily digested using the diagram

below.

Here s and t are any two states.

Whenever we have the red arrow we must also have the green self

loop. Here in is any input and out is any output.

This means that

as long as the input condition that caused the state transition

(from s to t) prevails, the current state must not

change, and the same output condition must prevail.

What's so magical about this condition?

Our main aim is to create the illusion of continuous time. For

this we are actually using a discrete time scale with a high

enough resolution, e.g., milliseconds. Now suppose

that you

press the FIRE button before time out. Until you release the

button each

millisecond tick produces the input tdF. Being only an ordinary

mortal, you can never predict the duration of the button press

correct to the nearest millisecond. So the exact number of tdF's

that the finite automaton sees is also not predictable. All that

can be guaranteed is that there will be a stretch of tdF's. The

length of the stretch will vary randomly from one press to

another, and is not important. The condition above makes the DFA

sensitive to the stretch, but insensitive to the length of the

stretch, by providing the green loop to ``eat up'' the stretch.

Notice, by the way, that the automaton for the text version violates

this condition.

|