|

www.angelfire.com/dragon/letstry

cwave04 at yahoo dot com |

|

|

|

A bit of abstraction

The great usefulness of finite automata stems from its abstractness. If we

learn to deal with this abstract concept then we can easily cast our

findings in any other

concrete set up and reap the benefit thereof. We have seen

in the last page that a finite automaton is simply a collection of 6

things (a 6-tuple) :

(A,B,S,f,g,START),

where

| Abstract symbols | In our Humpty Dumpty example |

| A is the (finite) input set |

A={Smile, Punch} |

| B is the (finite) output

set |

B={Normal, Smile, Raise eyebrow, Scowl, Growl, Grimace} |

| S is the (finite) state set |

S={Ordinary, Happy, Angry, Furious, Surprised} |

| f is the output controlling

function |

See below |

| g is the state controlling

function |

See below |

| START is a special member of S and is

called the initial state, the state from which

the automaton starts. |

START=Ordinary |

There are two popular ways to write down the

functions f and g, which we discuss below.

Method of tables

In this method f is written as a table. There

is one row for each state, and one column for each input. The table for

our Humpty Dumpty example from

the last page is shown below. To compare this with the example click

here.

|

Inputs |

| States |

|

|

Smile

|

Punch |

| Ordinary

|

Smile back

|

Raise eyebrow

|

| Happy

|

Smile back

|

Raise eyebrow

|

| Surprised

|

Normal

|

Scowl

|

| Angry

|

Scowl

|

Growl

|

| Furious

|

Scowl

|

Grimace

|

|

This table tells you to produce output f(a,s)

if your current input is a and the current state is

s. Simply look up the the entry in the row for

headed by s and column headed by a.

To fix the ideas let's do the following exercise. First click the example

link above (if you have not done so already) to open a

new small window containing only the Humpty Dumpty example. Turn the mind toggler

on, so that you can clearly see the states at each

step. Press reset to start the exercise. What is the state now ? It is

"Ordinary", which is the START state.

Suppose that the input is going to be "Smile". What

will be the output then? In other words what is

f(Ordinary , Smile)? The table tells

you that it is "Smile

back". Thus, pressing the

"Smile" button will cause Humpty Dumpty to "Smile back". Check

that this is

actually so by direct experimentation. Similarly try out

some other examples and compare with the table.

Next we shall discuss g, the

state controlling function. It can be

written as another matrix such that the entry in the row corresponding to

s and column

corresponding to a is

g(a,s):

|

Inputs |

| States |

|

|

Smile

|

Punch |

| Ordinary

|

Happy

|

Surprised

|

| Happy

|

Happy

|

Surprised

|

| Surprised

|

Ordinary

|

Angry

|

| Angry

|

Angry

|

Furious

|

| Furious

|

Angry

|

Furious

|

|

A cursory glance at the two tables may lead you to the wrong belief that

they are essentially the same with "smile back" in the first table is

always replaced by "happy" in the second one, and similarly "ordinary" by

"normal", "raise eyebrow" by "surprised" etc. But this not always true,

simply because there are unequal numbers of outputs and states. In

particular, look at the bottom righthand corner of the tables. It seems

that "grimace" in the first table corresponds to "furious" in the

second table. But the entry just above it belies this speculation. There

we have "growl" in the first table though the second table entry is still

"furious". We leave it to the reader to check correctness of the table by

direct experimentation.

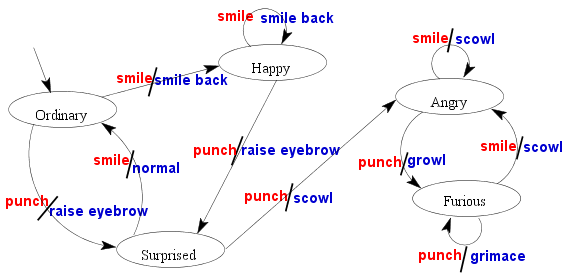

Method of diagrams

This is another method of representing the same information as conveyed by

the two tables above. It is best explained via an example. Below we construct

the diagram (called transition diagram) for our by-now familiar

Humpty Dumpty example.

The diagram, as the reader can easily see, consists of some nodes

shown here as ellipses labelled by the names of the states. A number of

arrows connect the nodes. Each arrow

is labelled by a pair of items separated by a comma. A close inspection

will reveal to the reader that the first item of the pair is always the

name of some input, while the second one refers to some output. Consider

for example the typical portion of the diagram shown below.

The diagram shows only two nodes, corresponding to the states "ordinary"

and "happy". The arrow leads from "ordinary" to "happy". The

label pair associated with this arrow is ("smile","smile back"). This means

that if Humpty is currently in the the "ordinary" state and the input

is "smile" then he produces the output "smile back" and (following

the arrow) internally moves to the state "happy".

This explanation does not, however, tell us anything about the tiny arrow

that leads from nowhere to the "ordinary" node in the complete

diagram. Well, it is not a typo. It simply says that

"ordinary" is our start state.

The reader may naturally ask "Which method is better --- the table one or

the diagram one?" There is no unique answer. The diagram method is more

appealing to the eye, and often easier to construct by hand. The table

method, on the other hand, is better suited to computer

implementation, a topic which are presently going to look into.

Implementing a finite automaton

For this section we assume that the reader is reasonably familiar with

some high-level computer language like C or ForTran. We shall present all

our code snippets in C. All our indices will start from 0 onwards.

Our C coding of a finite automaton will come as three modules.

- The matrix module

- The output module

- The driver module

The matrix module

The matrix module will consist of two matrices like those we have presented

in the method of tables above. To get these matrices we shall encode the

sets A,B,S as sets of integers as follows.

A = {0,1,...,nInput-1}

B = {0,1,...,nOutput-1}

S = {0,1,...,nState-1}

Here nInput,nOutput and nState refer ,respectively,

to the numbers of inputs, outputs and states.

The matrix outMat for the output controlling function, and

the matrix staMat for the state controlling function will

then be matrices like

int outMat[nState][nInput];

int staMat[nState][nInput];

|

Depending on the context, the exact entries in these matrices may be

hardcoded in the program (in the form of initialization) or read in from

some file during execution.

The output module

In our Humpty Dumpty example, the outputs were merely words

that denoted

some actions. In a reallife problem, however, mere words will not do, rather we

have to indeed perform some action. Actually, even in the toy

example, some action was performed, viz., the appropriate image was

highlighted. A little javascript program sitting behind the html file was

doing that service for us. Any such routine(s) helping us to perform the

output actions will go in the output module. A generic interface to this

module may be provided by an envelop routine output of the form

output(int whichOutput) {

switch(whichOutput) {

case 0:

/*write appropriate code

to handle output 1*/

break;

/* other cases go here */

case nOutput-1:

/* handle this output */

break;

default :

fprintf(stderr,

"Unknown output number [%d]\n",

whichOutput);

}

}

|

The driver module

This is in some sense the main module, though it is the simplest module to

write. It is a code with an infinite loop (assuming appropriate exit

statements to be embedded in the output module). It is so very simple that

it is better to give the code directly rather than try to complicate it

with explanations.

driver(int startState) {

int state, inp;

state = startState;

while(1) {

inp = input();

output(outMat[state][inp]);

state = staMat[state][inp];

}

}

|

As any experienced programmer will readily see, the above code is not

meant to be used verbatim for each and every problem that might call for

using a finite automaton. This is the working main core. The reader is

most welcome to modify the code to suit the problem at hand. In

particular, one modification that may be useful in many situations is to

remove the infinite loop, and make the routine carry out one single step

only. Then the user has to call the routine again and again to move

through the execution of the automaton. In this case it is important to

declare state as static inside the routine.

Now that the reader is resonably familiar with the implementation of

finite automata, it is time to take a look at some practical uses of

this concept.

|