"IT WAS QUITE EMOTIONAL AND FUNNY AND WEIRD AND BEAUTIFUL"

(Thanks to Jochen!)

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | August 2025 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

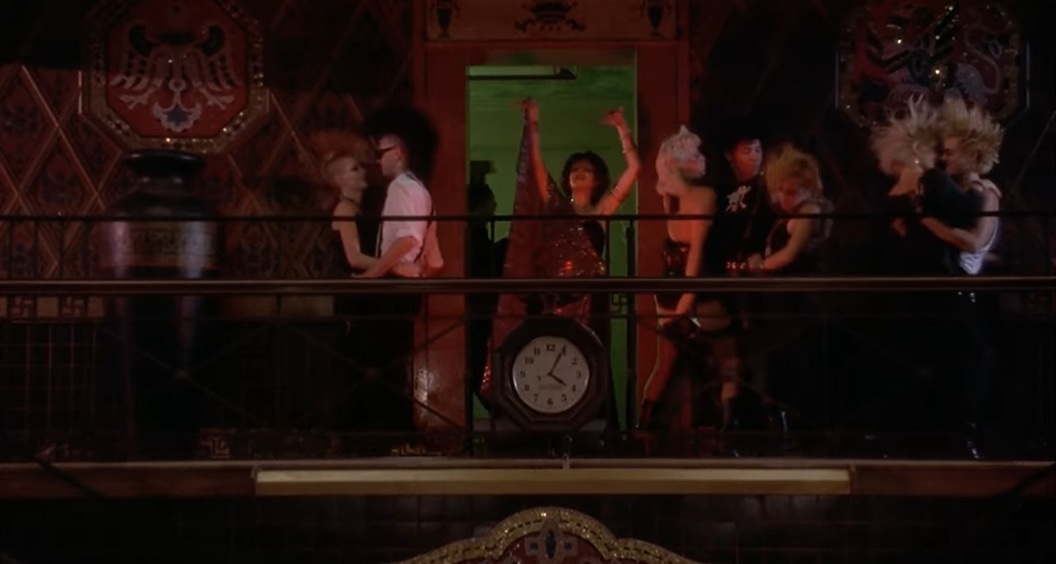

Offices of Death Records

Elsewhere in De Palma on De Palma, De Palma brings up Billy Wilder while discussing Carlito's Way:

Al [Pacino] and his friend, producer Martin Bregman, had been looking to do Carlito's Way for years. They worked with Edwin Torres, the author of the two books on which the film is based, and kept telling me that it was very different from Scarface. When I read the script I could see that it was indeed very different. The tone was more fatalistic, the story took place in the Seventies, and there was this agonising voiceover that reminded me of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard or Double Indemnity. I was immediately hooked.

KURT: After The Fury comes the ultimate De Palma film: Dressed to Kill.HOWARD: Dressed to Kill is important because thematically De Palma is at the height of his focus with ideas of femininity, masculinity, religion – in other words, things that in modern society have been made to cripple individuality and dwarf identity and sometimes remove identity, things that just shouldn’t belong in society for a successful society or for successful mental and physical health. And Dressed to Kill in 1980, we’re going out of the ‘70s now into a new era. And he just takes all this along with a slightly more self conscious wink to his own work. So in Dressed to Kill, sure, he’s making some very sophisticated jokes about psychology – obviously jokes, again, but look where he came from. He’s a satirist. He’s not going to let you forget this. So even though there’s this wonderful tricky story about who performed this horrible vivisection with a razor blade in an elevator, he starts to stack up the thought process of the mainstream commercial critics and the audience at the time. The whole point of Carrie was to provoke, provoke, provoke, then explode when your audience and your studio is just not getting it. This is going a little bit farther now. There are scenes in Dressed to Kill where he shows that. You could call it a wink or a spoof – I hate using that word, but it’s just to make you laugh: the very last scene is this dream that Michael Caine is coming for revenge on the woman who put him away, the prostitute played by Nancy Allen. It looks like Halloween! – this subjective camera moving outside the house. In the very next film that he made, Blow Out, he spoofs the spoof. He’s taking that and he’s making it obvious: “This is how you make that scene.” And he replicates the scene that he staged and shot as the dream in the climax of Dressed to Kill, and now he’s using that as an example of how a low-budget director makes a film. So the success of Dressed to Kill as a thriller, because it was shot so elegantly and poetically by Ralf Bode, when he moves on to Blow Out just a year later, it’s all self examination, self reflection, and everything is out in the open. “This is what I have to think about when I make something like this. I need a good scream. I need a good scream. How do I get that scream?” Of course that’s a play on Vertigo with Jimmy Stewart trying to figure out he’s going to get rid of his vertigo, and he has this whole contrived psychological horror thriller he has to put himself through just for the punch line – “Okay, I don’t have vertigo anymore.” And the end of Blow Out, it’s, “Okay, I got my scream.”

It's all connected. The language is all connected. I hate to say they’re jokes, but they are. They’re amusements to him, because this is why you do it. Dressed to Kill is important because once again, like Carrie, his ability to hone emotional capital from these characters was profound for that time. Movies that made you care about horror movies, that made you care about women – not putting them in distress porn horror, that’s not what he’s doing. He’s creating characters that you, the audience, are to identify with. Are you identifying with aspects of someone with transgender passion and an inability to break through that? Michael Caine’s character ultimately is quite a poignant character, especially the use of mirrors in that movie. Mirrors from the very opening scene are very important. What’s obscured? What’s hazed over by condensation? What’s visible? Michael Caine looking at himself in a mirror is so much more indicative of a pain that his character is dealing with which causes a schizophrenia, a violent combination of parts of your mind working against each other, ultimately trying to reconcile. But like Carrie’s mother did to Carrie, your upbringing is dwarfing your ability to process life naturally.

The end of that movie once again reiterates that the nightmare will stay with you if you’re someone who has compassion and who understands why you’re a human being, how you interrelate with other people, how you look at yourself and how you can be healthy or how you can be aberrant. This is not just a moral director but a voice of honest humanitarian concern. People overlook that completely. And Dressed to Kill is a phenomenally emotional film if you look at it even on the superficial level and you don’t look at the Hitchcock winks and jokes and nods.

For filmmaker Alex Ross Perry, whose new documentary Videoheaven (2025) considers the lifespan of video stores through their depiction in films and TV shows, trying to understand what happened to the video store was not simply an academic concern. Born in 1984, just a few months before Brian de Palma’s Body Double depicted a video store in a film for the first time, Perry spent his whole early adult life working in video stores. “My first job was at Suncoast video,” he told me in an interview on Zoom. “The whole time I was in college at NYU and then for a year and a half after, I worked at Kim’s Video on St. Mark’s between 2nd and 3rd Avenue.”Kim’s, which opened in 1987 and stayed open until 2008, was an extraordinary place, known for the size of its collection and the knowledge of its staff (a number of whom, like Perry, went on to become filmmakers). “Go to any film school, and you can draw a line around the thousand most canonical films,” Perry explains. “That’s what you’re getting. And that’s a lot. Kim’s had fifty thousand movies. And the idea that you came to one physical room to access these things was very special. It’s how I grew up.”

Over the years Perry, who has written and/or directed more than a dozen films, has pitched any number of stories involving video stores without success. Then he read Daniel Herbert’s 2014 book Videoland: Movie Culture at the American Video Store. In subsequent conversation with Herbert, he came up with the idea to document the depiction of video stores in film and TV shows, from their earliest portrayal in the eighties through to their collapse in the 2000s.

The more Perry dug into the project, the more he discovered a possible solution to this mystery he had been struggling with for so long. He acknowledges most believed there was no real mystery to solve: just as streaming is now cannibalizing cinema, it previously devoured the video rental business. But he was not fully convinced. “Yes, streaming started roughly the time stores went away, but so does music streaming—even earlier actually, and you can’t go to a small-town Main Street and not still find a credible music store.”

“Streaming didn’t end music sales—though it brought it very low. E-books didn’t end book stores.” So again, why was it different for video?

What he discovered in his research is that as the years went on, films and TV shows took a more and more hostile view of video stores. After initially portraying them as places where people are exposed to danger—David Cronenberg’s 1983 film Videodrome, though it doesn’t show a store, treats the video tape itself as a sort of monster we let into our houses—for a time video stores were imagined as spaces of discovery, even adventure. These were places where visitors had the chance to have richly curated cultural experiences, and also perhaps to experience for themselves the kinds of stories they watched. Clerks found themselves thrown into action movies. Customers looking for a romcom had their own meet-cutes. “This video space was advertised as a portal to a world of experience that was transportive,” Perry explains. “At Kim’s, you had fifty thousand futures waiting for you.”

But then other, darker ideas started to creep in. Video stores started to be presented as places where your own private desires were on public display, and as such, sites of potentially uncomfortable revelation. How many times have we watched scenes where someone hides the movie they want to rent because they’ve run into a friend or family member? Suddenly visiting a video store was like buying condoms or a pregnancy test at the pharmacy. “Being in public at the video store,” the film explains, “was a cause for concern.”

Likewise the knowledge and good taste that had been ascribed to clerks early on started to metastasize in movies and TV shows into characters who were condescending, belligerent, and at the same time, pathetic. They were, Perry writes in the film, “the modern equivalent of the eternally shushing fuddy duddy librarian,” but for some reason movies and TV shows made them a thousand times more intrusive and demeaning. Who would want to deal with people or places like that?

As video stores became a staple of modern life, Perry notes how movies and TV shows went one step even further, treating them as banal, brightly-lit, cookie-cutter purgatories, each with the same basic set of movies. Perry opens the film with a clip of Ethan Hawke in Hamlet wandering the aisles of a video store. Could there be any more fitting place to ask, “To be, or not to be?”

Let us give thanks for the good people at Sticking Place Books, a publishing company that has released everything from studies of Casualties of War to the poems of Abbas Kiarostami. Two of the latest releases are unreleased 1990s scripts from Brian De Palma (yay!) and David Mamet (boo—oh wait, this is a David Mamet work from three decades earlier—yay!) Russian Poland is the strange, compelling story of two Jewish World War II veterans on a mission into late 1940s Israel. De Palma’s Ambrose Chapel is the more enticing of the two scripts, and its release is, I think, very noteworthy. As James Kenney explains in his introduction, “Ambrose Chapel adopts the sleek posture of a geopolitical thriller, all international intrigue and stealthy rescues. But before we’ve even found our footing, games are underway.” Kenney says the script’s DNA is “deeply De Palma, but the tone is surprisingly giddy, even liberatory.” Actors whose names had been bandied about for starring roles include Brad Pitt, Liam Neeson, Tea Leoni, and even Madonna. What a shame Ambrose never took flight, but thank goodness we can ponder what might have been.

There is no one better suited to discuss film editing and sound design than Oscar-winner Walter Murch, the editor of a litany of greats: The Conversation, Apocalypse Now, The Godfather. His first book, 1992’s In the Blink of an Eye: A Perspective on Film Editing, is a classic. “Much has happened in those years,” Murch writes, “but the most significant development was the two-decades-long (1990-2010) transformation of cinema from an analogue to a digital medium. As I suggested in Blink, it is a shift whose closest analogy in the history of European art might be when oil painting began to displace fresco in the fifteenth century.” Suddenly Something Clicked goes to great lengths to not repeat details from Murch’s earlier book. Rather, it is a worthy companion. The chapters covering his work on The Conversation and the restoration of Welles’ Touch of Evil are riveting.

For as long as gangster movies have been made, costume designers have used clothing to visually communicate the difference between the flashier crooks—those who dress as loud as they act, often attracting law enforcement or a rival’s bullet—and their more subdued counterparts, who may be just as brutal but carry themselves with quieter menace that extends to their wardrobes. This dynamic is clearly illustrated through Patricia Norris’ costume design in Scarface, a movie in which few make it out alive—and those who do are rarely the ones drawing attention.Tony and Omar arrive in Cochabamba dressed in the de facto uniform of 1980s mid-level Miami coke dealers: low-slung, double-breasted suits in offbeat colors; non-white shirts unbuttoned to mid-chest with matching pocket squares; and plenty of gold flashing from their necks and fingers. In contrast, Alejandro Sosa presents a more refined image with his head-to-toe neutrals anchored by a silky windbreaker. Though some pieces mirror his visitors—like a low-buttoned shirt or pinky ring—Sosa’s look is ultimately more restrained, closer to smart, timeless sportswear than flashy criminal couture.

The most casually dressed man at the table—and also the one with the most power—Sosa sets himself apart in a creamy beige windbreaker likely made from silk or a silk-like synthetic fiber, soft and lightweight with a subtle luster that catches the South American sun. White inset stripes run down each sleeve from the shoulder seam to the elastic cuffs, adding a touch of sporty contrast.

A tonal plastic zipper runs up the front, offset by about an inch from the edge with a narrow storm flap tucked behind it, to a short standing collar—squared at the edges and fastened with a single beige button. Slanted hand pockets keep the design simple, while an inverted box pleat across the back adds mobility and contributes to the jacket’s fashionably loose, sporty drape—gently cinched at the waist by the elasticized blouson-style hem that sharpens the silhouette without sacrificing ease.

Matt Spaiser wrote for Bond Suits that “it takes both a bold and elegant man to wear a shirt made of voile.” While his description naturally applied to James Bond (the subject of his excellent blog), Alejandro Sosa also applies as such a bold and elegant man, who makes his first appearance wearing a white voile long-sleeved shirt layered under his windbreaker.

Voile is a lightweight, breathable fabric made from high-twist cotton or silk yarns, giving it a signature semi-sheer quality that sets it apart from similar weaves like poplin. Paired with its soft hand and wrinkle resistance, this subtle translucence makes it ideal for refined warm-weather attire. While most of the a voile shirt’s structure is sheer, reinforced pieces like the collar and placket are often more opaque due to the extra layer of fabric required.

Brian de Palma has a bit of a chilly personality, but I admire him as a director and technician. So when he offered me a rathar weird horror film called Dressed to Kill, I figured this was a gamble that might pay off. He was very demanding, often shooting on and on until he got precisely what he wanted. I remember one nine-page sequence that incorporated a 360-degree swing of the camera and required 26 takes (a record for me); whenever we actors got the scene right, the camera didn't and vice versa. That one sequence took a whole day to shoot.

The man is wearing sunglasses, a clear indication that he is not there to appreciate art. But this detail also foreshadows Bobbi, who hides her identity behind dark sunglasses, day and night. Through this association of two characters with “no eyes,” the stranger is the dark angel, the one who delivers Kate to Bobbi, her killer. This approach of connecting worlds is also present in a similar fashion in Psycho; Marion has fallen asleep on the side of the road and is awakened by a policeman, who is wearing dark sunglasses. He never takes them off; we never see his eyes. This very much presages the other character with no eyes, Norman Bates’s dead, mummified mother in the cellar. When she is revealed—as a lightbulb swings back and forth above her face—we see dark holes instead of eyes, just like the cop who wouldn’t take off his sunglasses.