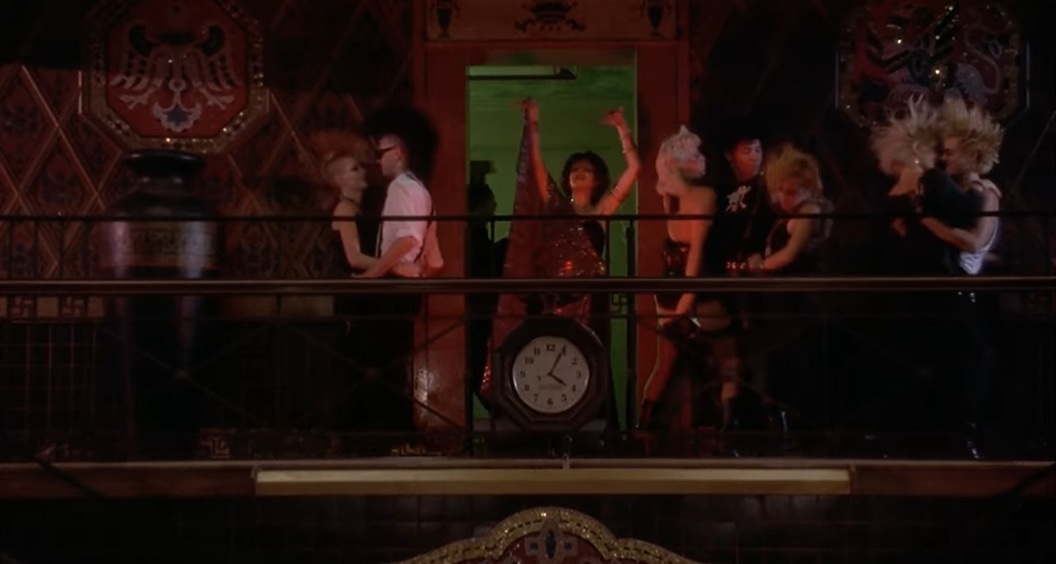

For filmmaker Alex Ross Perry, whose new documentary Videoheaven (2025) considers the lifespan of video stores through their depiction in films and TV shows, trying to understand what happened to the video store was not simply an academic concern. Born in 1984, just a few months before Brian de Palma’s Body Double depicted a video store in a film for the first time, Perry spent his whole early adult life working in video stores. “My first job was at Suncoast video,” he told me in an interview on Zoom. “The whole time I was in college at NYU and then for a year and a half after, I worked at Kim’s Video on St. Mark’s between 2nd and 3rd Avenue.” Kim’s, which opened in 1987 and stayed open until 2008, was an extraordinary place, known for the size of its collection and the knowledge of its staff (a number of whom, like Perry, went on to become filmmakers). “Go to any film school, and you can draw a line around the thousand most canonical films,” Perry explains. “That’s what you’re getting. And that’s a lot. Kim’s had fifty thousand movies. And the idea that you came to one physical room to access these things was very special. It’s how I grew up.”

Over the years Perry, who has written and/or directed more than a dozen films, has pitched any number of stories involving video stores without success. Then he read Daniel Herbert’s 2014 book Videoland: Movie Culture at the American Video Store. In subsequent conversation with Herbert, he came up with the idea to document the depiction of video stores in film and TV shows, from their earliest portrayal in the eighties through to their collapse in the 2000s.

The more Perry dug into the project, the more he discovered a possible solution to this mystery he had been struggling with for so long. He acknowledges most believed there was no real mystery to solve: just as streaming is now cannibalizing cinema, it previously devoured the video rental business. But he was not fully convinced. “Yes, streaming started roughly the time stores went away, but so does music streaming—even earlier actually, and you can’t go to a small-town Main Street and not still find a credible music store.”

“Streaming didn’t end music sales—though it brought it very low. E-books didn’t end book stores.” So again, why was it different for video?

What he discovered in his research is that as the years went on, films and TV shows took a more and more hostile view of video stores. After initially portraying them as places where people are exposed to danger—David Cronenberg’s 1983 film Videodrome, though it doesn’t show a store, treats the video tape itself as a sort of monster we let into our houses—for a time video stores were imagined as spaces of discovery, even adventure. These were places where visitors had the chance to have richly curated cultural experiences, and also perhaps to experience for themselves the kinds of stories they watched. Clerks found themselves thrown into action movies. Customers looking for a romcom had their own meet-cutes. “This video space was advertised as a portal to a world of experience that was transportive,” Perry explains. “At Kim’s, you had fifty thousand futures waiting for you.”

But then other, darker ideas started to creep in. Video stores started to be presented as places where your own private desires were on public display, and as such, sites of potentially uncomfortable revelation. How many times have we watched scenes where someone hides the movie they want to rent because they’ve run into a friend or family member? Suddenly visiting a video store was like buying condoms or a pregnancy test at the pharmacy. “Being in public at the video store,” the film explains, “was a cause for concern.”

Likewise the knowledge and good taste that had been ascribed to clerks early on started to metastasize in movies and TV shows into characters who were condescending, belligerent, and at the same time, pathetic. They were, Perry writes in the film, “the modern equivalent of the eternally shushing fuddy duddy librarian,” but for some reason movies and TV shows made them a thousand times more intrusive and demeaning. Who would want to deal with people or places like that?

As video stores became a staple of modern life, Perry notes how movies and TV shows went one step even further, treating them as banal, brightly-lit, cookie-cutter purgatories, each with the same basic set of movies. Perry opens the film with a clip of Ethan Hawke in Hamlet wandering the aisles of a video store. Could there be any more fitting place to ask, “To be, or not to be?”