"HER HAIR, MAYBE. IT WAS BRIGHT RED. LIKE IT WAS ON FIRE."

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

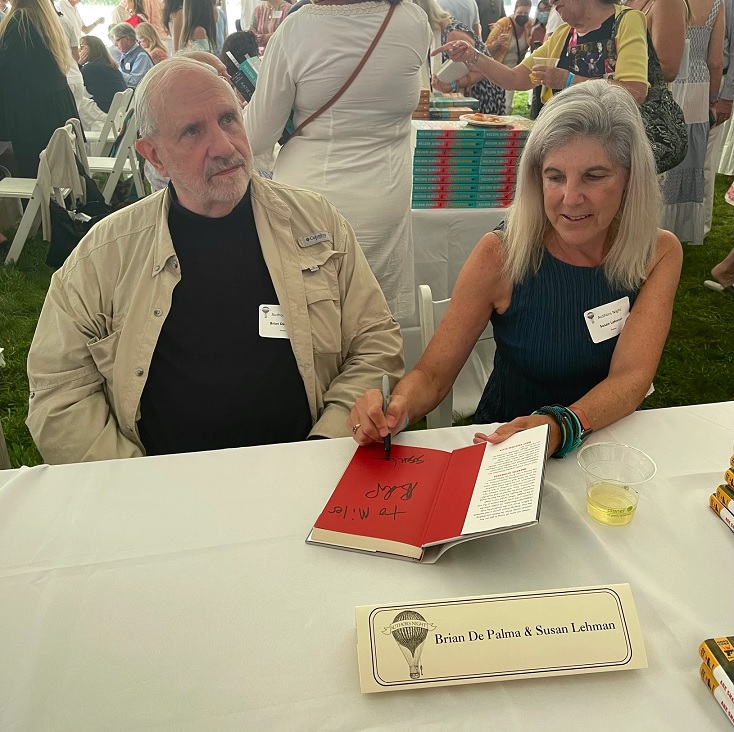

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | September 2022 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Dua Lipa as a tourist in Buenos Aires

Happy Birthday, #briandepalma ! It is his 82th, 9/11, all too easy to remember. I met the great director of stylish elegant violent eccentric unforgettable movies like #carrie, #dressedtokill, #blowout, #scarface, #bodydouble, #theuntouchables, #missionimpossible and more at a small private dinner party in Hamburg in 1993. He was in town to promote #carlitosway, starring #alpacino and #seanpenn. I was in the midst of shooting my lowbudget feature #rotwangmussweg. I went to the dinner with an impossible plan: to persuade Brian De Palma to appear in a #cameo in my film the very next day. After I explained the scene I wanted him for he pointed to an almost full bottle of #grappa on the table: Finish this with me and I‘ll do it. The bottle was empty by two AM. More than a little drunk I called my producer Patrick Brandt to tell him about the coup. Ten hours later we set up our camera in front of famous #atlantichotelhamburg. Brian kept his word. He came down the hotel stairs and improvised a scene with our actor #klausbueb who played the former director of the defunct film department of the East German Secret Service #stasi trying to show his work to powerful American filmmaker Brian De Palma. We shot the scene twice, De Palma being De Palma, brushing off the nervous man with the bearskin hat in the first version, inviting him into his hotel suite as a fellow artist in the second. We used both of them, the second one as a dream sequence. The #cameo appearance was a very generous gesture on Brian‘s part. I admire his work, I admire the man. May he live long and make some more brilliant movies. #rotwangmussweg is available on #dvd.

After its momentous debut in The Black Cat, modernism did not appear as a villain’s lair again until Hitchcock brought it back in the mid–20th century with North by Northwest. The return of high-end modern designs on film corresponded with a critical shift in the portrayal of evil characters, morphing from a frazzled Dr. Frankenstein into a handsome Captain Nemo. Using cultivated gentility to cover malign intentions required an equally sophisticated architectural expression. One of Hitchcock’s first experiments with this portrayal is seen in The Secret Agent, in which he unveiled a villain who was “attractive, distinguished,” and “very appealing” to audiences, according to his biographer François Truffaut. Hitchcock moved forward from there with the belief that “the best way” to make a thriller work was to “keep your villains suave and clever—the kind that wouldn’t dirty their hands with ordinary gun play.”The building that changed movies forever makes its first appearance almost two hours into North by Northwest and is onscreen a mere 14 minutes. Filmic structures are “evanescent as a flicker of light,” as noted by historian Alan Hess. Nonetheless, this design had a penetrating and lasting effect in the public consciousness. The Vandamm House itself is now a movie star with its own dedicated legion of fans. The high-quality production design of the film, and the hybrid mixing of recognizable locations with studio sets, led to many inquiries as to the “real” location of the home. Explorations in the area behind Mount Rushmore would prove futile, however, as the building is entirely conjectural, a set created by production designer Robert F. Boyle at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios in Los Angeles.

In the decades following the release of North by Northwest, filmmakers enthusiastically adopted Hitchcock’s architectural precedent, crafting fictional modernist structures and rediscovering designs in Southern California that could host a score of film villains introduced in the 1960s and ’70s. Architect John Lautner designed many houses during this period that later found fame as villain’s lairs. His tactile, sensuously curved, concrete spaces exude power in their boldness and unorthodox approach. Filmic creators also appreciated the cinematic scale and the ambitiousness and improbability of the designs. Ken Adam, production designer for the James Bond series of films including Dr. No, Goldfinger, Thunderball, The Spy Who Loved Me, and Moonraker, featured the Lautner-designed Arthur Elrod House in Palm Springs in Diamonds Are Forever. Bond (played with finesse by Sean Connery) tracked billionaire Willard Whyte to his lair in the hills, protected by the acrobatic Bambi and Thumper. The women swing from the modern lighting, leap from the living room boulders, and attempt to drown Bond in the sky-high swimming pool. The perfect hideaway for a villain.Director Brian De Palma selected the Chemosphere, another cliff-hanging Lautner design, for Body Double, a murderous homage to both Vertigo and Rear Window. The film, and the building, draw upon prevailing narratives of voyeurism, identity, and complicit shame explored by Hitchcock. Jeannine Oppewall, an Academy Award–nominated production designer for L.A. Confidential (featuring the Richard Neutra–designed Lovell House in its own villainous star turn), noted that in her line of work, “the best architecture [goes] to the film’s worst characters.”

Hitchcock manipulated our collective memory and the language of building design to create constructed expressions of human emotions, including love, envy, and the killer instinct. He was driven by an intense engagement with location and architectural form, picturing buildings not only as scenic devices but as interactive participants. For Hitchcock, the parts of a structure represent humanity and all its complications: Windows are the eyes into the soul, a stairway is a spine between the heart and mind, and a door permits entry into subliminal perceptions. His buildings—including the maternal Victorian mansion and naughty motel along the old highway in Psycho, the honeycomb of Greenwich Village apartments in Rear Window, the avian-infested Bodega Bay schoolhouse in The Birds, and the deadly skyscrapers and towers of Vertigo—illuminate the uncertain relationships we hold inside our own minds, with the built world around us, and between each other.

DEADLINE: You talked about finding common ground in your work. But the way you’ve explored this sense of otherness has been distinct each time. Are you purposefully seeking out new stones to turn over, even if they belong to the same garden?GUADAGNINO: I think the thing that most excites me as a filmmaker and a director is the possibility of fully exploring the craft, and really playing with the set of tools you have in your hands within the language of cinema. The more conscious I become about cinema, through the way I work and through learning the formal language of cinema in its many, many layers, it’s something that’s truly amazing.

I respect so much the work of filmmakers who repeat their same movie over and over again. It’s actually reassuring and beautiful to see that. But at the same time, that’s not who I am and how I am. I like the idea of trying things, as you said, to turn different stones in the same garden. I don’t know if the garden is my garden, the garden of my imagery, or what the great historian of cinema Georges Sadoul said in his seminal Histoire générale du cinema, Tome 1, which is that cinema is about human beings because it’s about telling the story of human beings. That might sound parochial, banal, or old-fashioned, again, but I think he was right. Even the most experimental work of Pat O’Neill, which I adore, or the great experience of the underground cinema in the ’60s and ’70s, still reflects on that.

DEADLINE: Equally banal, perhaps, but that idea that the universal can be found in the specific is something mainstream cinema often neglects.

GUADAGNINO: Every-size-fits-all is Walmart. Every-size-fits-all is an artificial concept that belongs to the practices of capitalism, and the execution of a dull idea of capital. A smart idea of capital comes with the notion of prototype; it comes with the idea of finding new territory in order to expand even more.

The reiteration of something that has been set in stone and repeated and repeated over and over again is a bad practice because it’s pollution. It’s the pollution of imageries, of the world, and it makes the environment less livable, and thus less consumable. It’s a strange contradiction.

Billy Wilder said that show business is show business because without business it’d be show show, which from his perspective was the greatest sin of all. I’m not sure I’m totally in agreement with Mr. Wilder. Still, let’s hold on that, because this is Deadline Hollywood. But at the same time, you have to make prototypes because you have to re-create again and again the possibility of excitement in the investment of an audience toward something truly new.

Even Top Gun: Maverick, which is a movie that trades very deeply with nostalgia and repetition, comes with the novelty of happening 25 years later. The idea that a sequel comes after a quarter of a century is, in its way, a very smart, intelligent, and thoughtful way of doing business. Because now, even if the movie holds very deep nostalgia in the audience—the nostalgic gaze of Tony Scott and the idea of the world in the way it was in 1986—you are there for the ride of Tom Cruise’s Maverick being a man now, not a boy. So, I would say there are always ways to create something that is surprising and interesting.

DEADLINE: And yet, the industry revels in its love of data.

GUADAGNINO: Yes, but we’re not working on parameters that are set in stone, like chemistry or physics or mathematics. We are working with something that deals with the unconscious, and we have to allow that to be cunning. If we trade in the unconscious for the algorithm of it all—whether it’s the algorithm itself or the expectations that come from it—that is where you fail. “You can’t do that because our data tells us the audience wants this.” Well, that way you would never have had The Godfather. You would never have had GoodFellas. You’d never even have had Mission: Impossible, the first movie by Brian De Palma.

And by the way, that’s true of The Godfather: Part II, and Part III, which I love. It’s my favorite of the three. I’m using this platform to say it: it’s a masterpiece. I go back to the Godfathers over and over, but I go back to Part III every six months. I wish I could have done a movie like that; it’s beautiful. Coppola is a forger of prototypes. Even now, with Megalopolis. He’s not doing it in a cheap way, he’s making a big movie out of it.

DEADLINE: The question is whether the industry that allowed for films like The Godfather and Apocalypse Now still exists, or whether the data is too powerful now.

GUADAGNINO: Probably not as a system, in the way the system worked back then. But definitely, it exists as individual personalities finding their own ways into the business. We have to see what happens and how things morph, and not be too disheartened by the present because there are new ways to find and be excited about.

That’s what I say to young filmmakers when they ask me how to break into filmmaking: just do it. And don’t allow anybody to let you down or lecture you about what to do and how to do it. Just do it. A filmmaker has to be a very obsessive person who must refuse to let people f*ck with him, her, or them. It’s a director’s medium.

When I spoke with De Palma, I asked him why he thought there was this trend of filmmakers turning to novels. Action flick auteur Michael Mann released Heat 2: A Novel this month and screenwriter David Koepp (Jurassic Park, Spider-Man, Panic Room) released his novel this June. He said that during the pandemic lockdown many filmmakers that usually had access to sets, studio budgets, and large casts and crews were forced to get back to the basics and write in a solitary way in their homes. I’ve spoken to movie junkie friends recently who rarely pursue novels who have told me that they can’t wait for the new Heat book or De Palma thriller. It’s a fascinating trend in a time when teens and young adults spend more time on digital media and less time reading; is it possible that the pandemic-induced disruption of film production caused a temporary youth literary revival?

When I spoke with De Palma, I asked him about his use of the split diopter shot. He said it was inspired by the deep focus shots of Citizen Kane where Orson Welles (and cinematographer Gregg Toland) held things in the foreground and far background in equal focus, granting the film these epic and vast spaces captured in a single frame. Shot on 35mm celluloid with an aspect ratio of 1.37:1, these deep focus shots were often used to place symbolic value on characters like the famous blocking of the young boy outside in the window frame while his family discusses his fate inside (This shot is studied in Film 101 classes all over the world).De Palma, meanwhile, wanted to juxtapose two images in striking contrast in the same frame, and collaborated with his cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond to use a technique called the split diopter shot to pack the frame with bursting color and multiple, deep focus-like layers of composition. An example of this can be seen when Travolta stands on a bridge listening to an owl in a far away tree top and yet they are sandwiched side by side, their heads occupying equal halves of the frame.

Another example is when a woman walking alone at night through the back door of a supermarket is thrust together with a shot of a man far behind her pulling an ice pick out of a seafood display next to a fish head.

These kinds of inventive visuals are why De Palma is so often concerned with the position of the camera as much as the subject. In a 2011 interview, De Palma said, "A dirty word to me is coverage... two-shot, over-the-shoulder. You know, stuff you see all the time drives me crazy because this to me is not directing." This is a common critique you'll hear from auteurs, like when Michael Mann criticized the kind of passive filmmaking where an action is going on and someone just happens to be there in the room to shoot it. Real directing, real filmmaking — if it exists — is this kind of brilliant visual storytelling that actively organizes and manipulates the interplay of striking images to evoke something from a viewer.

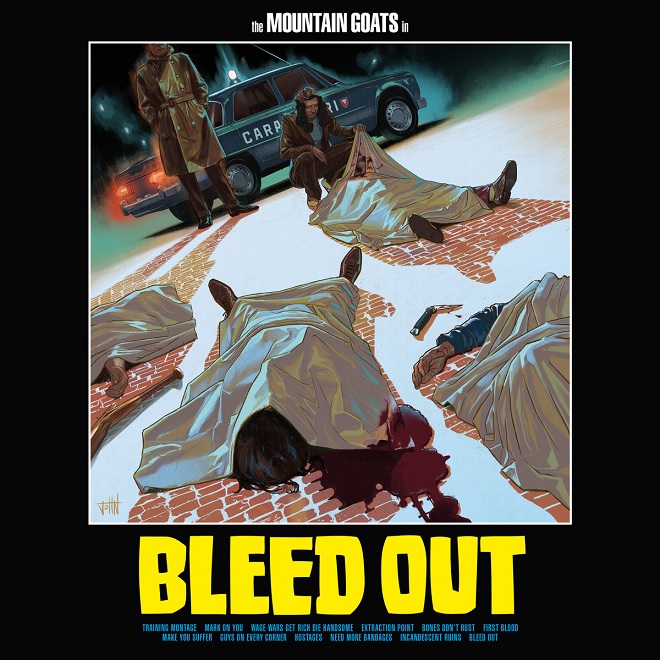

Spiritually similar to 2016’s Beat the Champ, an album that is about his love of professional wrestling, Bleed Out is head to toe inspired by his love of the cheese and the sleaze of revenge thrillers. “When people say ‘it’s so bad it’s good,’ that’s not correct. That’s not what I’m talking about. It’s that there’s, in a sense, obviously, not anyone can make a great movie, but sort of anyone with the capability can make a great movie, but every ‘off’ movie is off in its own way, and there’s real humanity …” (He interrupts himself to talk about Carnival of Souls).The album’s tone is set by its opening track, “Training Montage”, in which he declares quite decisively, “I’m doing this for revenge! / I’m doing this to try and stay true! / I’m doing this for the ones they had to leave behind! / I’m doing this for you!” This song lets you know exactly what you’re getting into here, in much the same way an action movie needs to set its tone in the first five minutes, lest it is mistaken for a romance.

Keeping things upbeat and amped up, “Wage Wars, Get Rich, Die Handsome” embodies the glory of the action hero, maybe the leader of a heist gang, maybe not the kind of guy you’d want to invite to a dinner party, but certainly one you’d enjoy watching blow shit up on-screen. Even its liner notes stay on theme.

The album is a rocker with some flares of saxophone and accompaniment by Alicia Bognanno from the band Bully, who also served as producer. Darnielle is a master storyteller, and Bleed Out is a kind of short story collection of heists, gang wars, car chases, and shootouts (less about plots and more about the feelings of the humans doing the action), utilizing all of the themes and tropes from his favorite titles. It is an album made up almost entirely of bangers, but it closes with a sigh of relief as its protagonist prepares for death. Reflecting on the ephemeral nature of existence, the narrator sings, “There’s gonna be a big spot where I once lay / And then there won’t even be a spot one day / Bleed out / I’m going to bleed out.”

The first movie John Darnielle of the Mountain Goats saw in a movie theater was The Wizard of Oz. It was 1971, and he was four or five. “That night, I very solemnly announced to my parents that I was going to marry Judy Garland when I grew up.” Aside from remaining a lifelong, dedicated Judy Garland fan, the screening of Oz left a lasting impression on him. “It was a very big experience for me,” he says. “I was utterly bowled over.”

This relationship with film would continue into adolescence during the late 1970s when parenting was less strict and he would get dropped off at the movies after school by himself. One standout from this time was 1977’s Orca, about a killer whale that gets revenge on a fishing boat that killed its pregnant mate. This thirst for stories of revenge started early. Of course, there were the daytime monster movies that would come on TV when they were living briefly in Milpitas, California (a location that appears in his latest novel). A favorite at the time was The Crawling Eye, a film that would appear two decades later on Mystery Science Theater 3000. A number of these elements would influence Darnielle’s more lurid cinematic tastes.

His entry into foreign films came courtesy of his stepfather (a character fans will remember as the villain of the Mountain Goats’ Sunset Tree album) and a recurring Sunday night film series at Pitzer College. Of his stepfather, Darnielle tells me: “He had grown up in a small Indiana town and aspired to be greater and learn things, and he would take me to foreign movies and teach me about Bergman, Pasolini, Fellini—those were his, sort of, big names.”

Darnielle favored Andy Warhol and was able to see his film, Trash, as a teenager. “It was a big night for me when I was 14,” he says. “If you wanted to see a Warhol movie, you just couldn’t; they weren’t around. He was, for those of us who listened to the Velvets, this legendary figure. You wanted to see what his movies were like. And Trash was a big, big thing for me.”

The programming at the Pitzer College Sunday night film series in Avery auditorium was every Sunday night for Darnielle. This is where he saw Kurosawa‘s Ran and Rashomon, Brian De Palma’s Blow Out, Wim Wenders’ Paris, TX, and of course, Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander. These were formative, taste-making years. He was hooked—a certified cinephile. “We would all go, me and my friends Tom and Steve, the would-be intellectuals. We’d go to movies from seven to nine and then at nine go out for coffee and argue about what we’d seen.”