CHARACTER ACTOR IN 3 BY DE PALMA - SNAKE EYES, THE BONFIRE OF THE VANITIES, THE BLACK DAHLIA

Updated: Sunday, August 24, 2025 10:20 PM CDT

Post Comment | View Comments (1) | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | August 2025 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

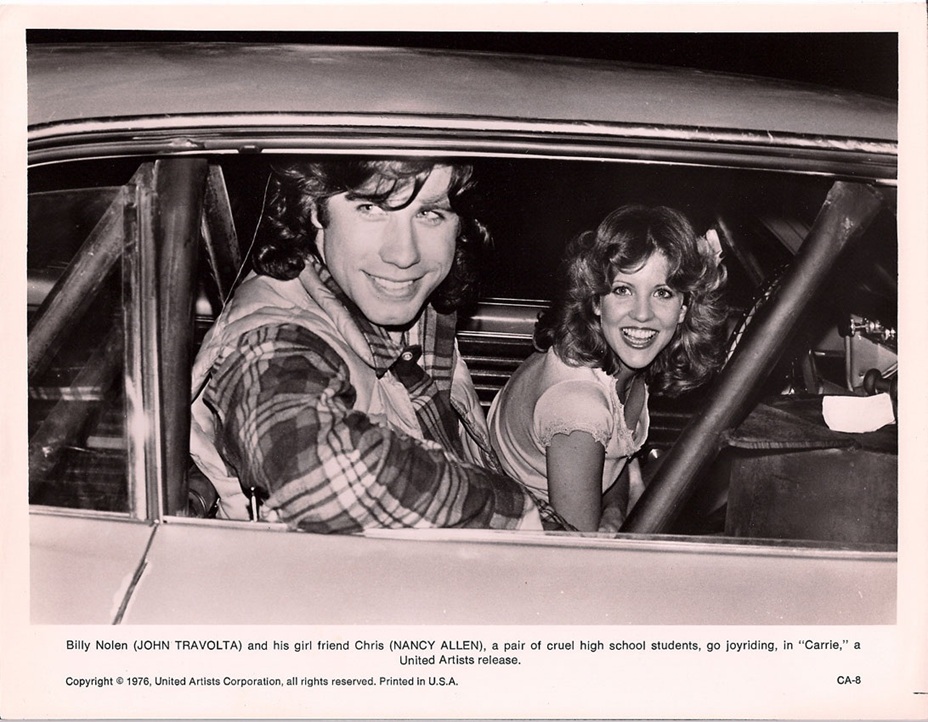

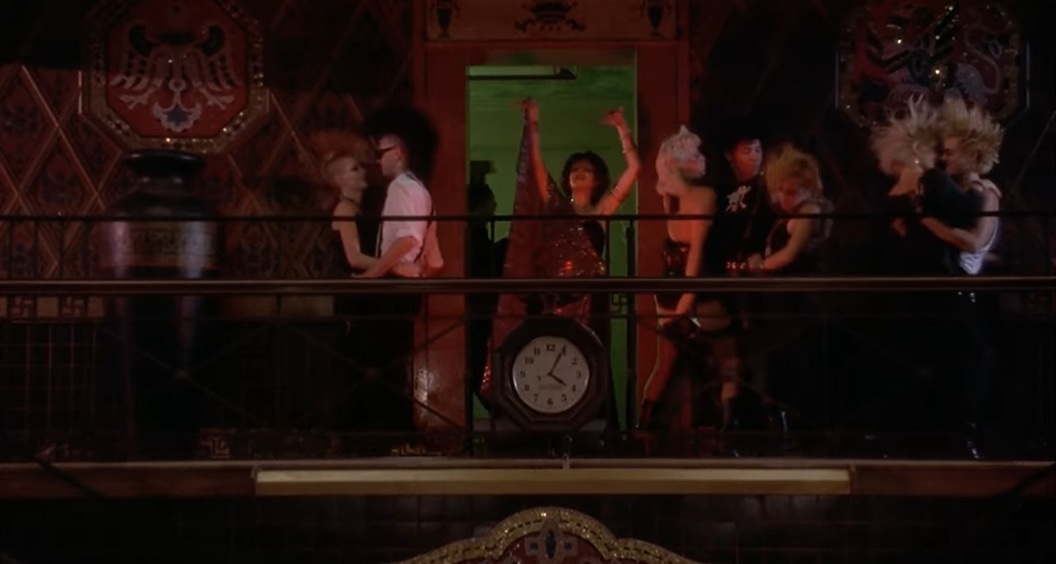

32 “Phantom of the Paradise” (dir. Brian De Palma, 1974)The fate of the midnight movie is still pretty much at the mercy of kids who can’t decide if they should cancel each other for liking “The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” But Brian de Palma’s “Phantom of the Paradise” reigns supreme as the definitive best piece of flashy genre cinema from the 1970s — a glorious ode to a rocker punished for his passion that was itself tortured on its rocky road to theaters.

Thanks to a nonsensical legal challenge from Led Zeppelin, moviegoers have to be pretty lucky to catch De Palma’s extraordinary 1974 glam opera as it was meant to be seen. Censorship plagues all publicly available versions of the film, and a particularly egregious restoration from a physical media release a few years ago left many fans disturbed by the intricate production details lost to its poorly updated color.

Still, whichever version you watch, the tragic tale of musical genius Winslow Leach (William Finley) shines through as a timeless testament to the power of talented freaks with a song to sing. Paul Williams scored “Phantom of the Paradise,” which also casts the Grammy-winning composer as the villainous namesake executive for Swan Records. Swan destroys what could be a quick rise to fame for Winslow and his band, The Juicy Fruits, when he steals the basis for their first hit song.

Enter Beef (Gerrit Graham), a competitive diva whose effort to help Swan screw over Winslow ends explosively. The glittery terror that surrounds that reveal commingles bejeweled platforms and fishnets (with some of the more disturbing elements of the Gypsy Rose Blanchard story?) in a singular “Phantom of the Opera” homage. It also sees “Suspiria” final girl Jessica Harper centerstage as its fresh-faced Angel of Music in a performance that could almost make you forget the movies’ later attempts at creating their own Christine. —AF

41 “Suspiria” (dir. Dario Argento, 1977)Shudder’s “Dario Argento Panico” is an essential documentary primer for any cinephile just getting into the complex, supersaturated legacy of Italy’s most notorious genre filmmaker. Understanding the dark psychology of a man who conjured up unfathomable suspense and horror — then repeatedly cast his real wife and kids as exquisite centerpieces in those artful nightmares — is, how do you say, “tutta una cosa.” That’s Italian for “a whole thing,” and basically the entire point for dedicated fans of the director.

Effectively standing in for a decade of brilliant giallo on this list, “Suspiria” is more than up to the task. The eerie magic Argento first conjured up in 1977 is best remembered for its illustrious use of color, even with “Deep Red” right there in the director’s filmography. The crimson splatters and jewel-colored glass that adorn the German ballet school where “Suspiria” takes place make it a crowning achievement in the pantheon of visual horror. That masterful dreamscape is reflected in the eyes of a young American dancer, Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), whose serpentine descent into supernatural madness plays out like a lethal recital on psychedelics.

Loosely translated, “Suspiria” means “breathing” or “to take a deep breath.” That quietly sensual undercurrent might explain why “Challengers” director Luca Guadagnino and “50 Shades” muse Dakota Johnson teamed up to revive Argento’s classic as a high-concept art film with a well-disguised Tilda Swinton in the critically-acclaimed remake from 2018. The original can’t evoke quite the same visceral response as that film’s updated effects, but anyone whose seen the atrium-hanging sequence should be able to convince you to watch both versions. Trite but true, there’s more than one way for a witch to step on your neck. —AF

Fifty years after its initial release, Rocky Horror has amassed global adoration, particularly on the midnight movie circuit. And no cinema in the world is more steeped in Rocky Horror’s rituals and traditions than the Clinton Street Theater in Portland, Oregon, which has shown the film every week without fail since 1978. “We’re certainly not a standard movie theatre,” co-owner Aaron Colter tells me.Currently managed by a collective of six co-owners, including Colter, the 300-capacity Clinton Street Theater stands as one of the oldest continually operating cinemas in the United States. Since its opening in 1915, it has flirted with being a cinema block-booked by specific film studios and, later, an adults-only cinema. It was in 1975 that it began operating through shared ownership, with five free-spirited and like-minded film fans buying the space together, one of whom was Lenny Dee. “I thought people needed a model of a different kind of business to the one we currently had, and the ideas and passions media contains can be an important thing to present to people,” he remembers. “Those were my two driving forces.”

Dee was the original booker of Rocky Horror, and thus technically the originator of the tradition. He first watched it as part of a programmed double bill with Phantom of the Paradise, Brian De Palma’s 1974 comedy-horror musical. “I actually liked that better than Rocky Horror, but I couldn’t get Phantom and wound up with Rocky Horror,” he remembers. “Then the fans kept coming.” That’s not to say Dee isn’t a fan of the movie; he estimates he’s seen it more than 300 times during his eight years of projecting it throughout the Seventies and Eighties.

It took time for Rocky Horror to take hold. The film initially sank like a stone upon release in 1975, with the critic Roger Ebert noting that “it was pretty much ignored by everyone”. Less than a year later, however, New York’s Waverly Theater decided to programme the film as a “midnight movie”, and it was there that schoolteachers Louis Farese Jr, Theresa Krakauskas and Amy Lazarus originated the props and audience interaction that would come to define the Rocky Horror cinema experience.

Dealing, which was based on a novel by Michael Crichton, will screen at the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica at 3pm this Sunday, August 17th. This American Cinematheque event will include a Q&A with filmmaker Paul Williams and actors Barbara Hershey and John Lithgow. Moderated by Larry Karaszewski.

The first time I watched Brian De Palma’s Scarface, I chuckled when the dedication to Howard Hawks and Ben Hecht appeared on screen over the carnage of the climax’s final moments. Because of Scarface’s notoriety, this, like so many first-time viewings of R-rated films, was at the end of a surreptitious late-night, post-parental bedtime watch after renting the film’s two-tape VHS version from a local video store. At the time, I didn’t know Hecht’s name, only Hawks’. And though I’d seen and loved some of his films, like Bringing Up Baby and His Girl Friday, I mostly associated Hawks with my vague notions of Hollywood’s classy Golden Age. I could only assume that the garish, provocative, grotesquely violent spectacle I’d just watched—the one that had stirred up such controversy a few years earlier—had virtually nothing to do with the original film. It would be years before I learned how wrong I was.It’s not just that the 1983 Scarface, directed by De Palma from a script by Oliver Stone, shares the same overarching rise-and-fall plot with the 1932 film, written by Hecht with a handful of other writers, adapted from a novel by Armitage Trail that itself was inspired by the life of Al Capone. It’s not even that De Palma’s Scarface borrows numerous elements and story beats from the original, including a protagonist who’s uncomfortably fixated on his kid sister and who sees a vision of his own future in an advertising slogan reading “The World Is Yours.” Though never as explicitly violent (and 100% chainsaw free), Hawks’ film is just as savage in its way as Scarface’s later incarnation. Both tell the stories of men who see America as a place where fortunes are to be taken and of the country that allows them to thrive, at least for a little while.

Elsewhere in De Palma on De Palma, De Palma brings up Billy Wilder while discussing Carlito's Way:

Al [Pacino] and his friend, producer Martin Bregman, had been looking to do Carlito's Way for years. They worked with Edwin Torres, the author of the two books on which the film is based, and kept telling me that it was very different from Scarface. When I read the script I could see that it was indeed very different. The tone was more fatalistic, the story took place in the Seventies, and there was this agonising voiceover that reminded me of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard or Double Indemnity. I was immediately hooked.

KURT: After The Fury comes the ultimate De Palma film: Dressed to Kill.HOWARD: Dressed to Kill is important because thematically De Palma is at the height of his focus with ideas of femininity, masculinity, religion – in other words, things that in modern society have been made to cripple individuality and dwarf identity and sometimes remove identity, things that just shouldn’t belong in society for a successful society or for successful mental and physical health. And Dressed to Kill in 1980, we’re going out of the ‘70s now into a new era. And he just takes all this along with a slightly more self conscious wink to his own work. So in Dressed to Kill, sure, he’s making some very sophisticated jokes about psychology – obviously jokes, again, but look where he came from. He’s a satirist. He’s not going to let you forget this. So even though there’s this wonderful tricky story about who performed this horrible vivisection with a razor blade in an elevator, he starts to stack up the thought process of the mainstream commercial critics and the audience at the time. The whole point of Carrie was to provoke, provoke, provoke, then explode when your audience and your studio is just not getting it. This is going a little bit farther now. There are scenes in Dressed to Kill where he shows that. You could call it a wink or a spoof – I hate using that word, but it’s just to make you laugh: the very last scene is this dream that Michael Caine is coming for revenge on the woman who put him away, the prostitute played by Nancy Allen. It looks like Halloween! – this subjective camera moving outside the house. In the very next film that he made, Blow Out, he spoofs the spoof. He’s taking that and he’s making it obvious: “This is how you make that scene.” And he replicates the scene that he staged and shot as the dream in the climax of Dressed to Kill, and now he’s using that as an example of how a low-budget director makes a film. So the success of Dressed to Kill as a thriller, because it was shot so elegantly and poetically by Ralf Bode, when he moves on to Blow Out just a year later, it’s all self examination, self reflection, and everything is out in the open. “This is what I have to think about when I make something like this. I need a good scream. I need a good scream. How do I get that scream?” Of course that’s a play on Vertigo with Jimmy Stewart trying to figure out he’s going to get rid of his vertigo, and he has this whole contrived psychological horror thriller he has to put himself through just for the punch line – “Okay, I don’t have vertigo anymore.” And the end of Blow Out, it’s, “Okay, I got my scream.”

It's all connected. The language is all connected. I hate to say they’re jokes, but they are. They’re amusements to him, because this is why you do it. Dressed to Kill is important because once again, like Carrie, his ability to hone emotional capital from these characters was profound for that time. Movies that made you care about horror movies, that made you care about women – not putting them in distress porn horror, that’s not what he’s doing. He’s creating characters that you, the audience, are to identify with. Are you identifying with aspects of someone with transgender passion and an inability to break through that? Michael Caine’s character ultimately is quite a poignant character, especially the use of mirrors in that movie. Mirrors from the very opening scene are very important. What’s obscured? What’s hazed over by condensation? What’s visible? Michael Caine looking at himself in a mirror is so much more indicative of a pain that his character is dealing with which causes a schizophrenia, a violent combination of parts of your mind working against each other, ultimately trying to reconcile. But like Carrie’s mother did to Carrie, your upbringing is dwarfing your ability to process life naturally.

The end of that movie once again reiterates that the nightmare will stay with you if you’re someone who has compassion and who understands why you’re a human being, how you interrelate with other people, how you look at yourself and how you can be healthy or how you can be aberrant. This is not just a moral director but a voice of honest humanitarian concern. People overlook that completely. And Dressed to Kill is a phenomenally emotional film if you look at it even on the superficial level and you don’t look at the Hitchcock winks and jokes and nods.