DE PALMA'S FILMS "SURE DO HAVE A LOT OF GREAT ROLES FOR WOMEN"

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | February 2023 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | ||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

In a The Hollywood Reporter obituary, Chris Koseluk writes that Belzer found "further fame as the cynical but stalwart detective John Munch on Homicide: Life on the Street and Law & Order: Special Victims Unit." Koseluk continues:

Belzer died early Sunday at his home in Bozouls in southwest France, writer Bill Scheft, a longtime friend of the actor, told The Hollywood Reporter. “He had lots of health issues, and his last words were, ‘Fuck you, motherfucker,'” Scheft said.Belzer made his film debut in the hilarious The Groove Tube (1974), warmed up audiences in the early days of Saturday Night Live and famously was put to sleep by Hulk Hogan.

Munch made his first appearance in 1993 on the first episode of Homicide and his last in 2016 on Law & Order: SVU. In between those two NBC dramas, Belzer played the detective on eight other series, and his hold on the character lasted longer than James Arness’ on Gunsmoke and Kelsey Grammer’s on Cheers and Frasier.

Certainly one of the most memorable cops in TV history, Munch — based on a real-life Baltimore detective — was a highly intelligent, doggedly diligent investigator who believed in conspiracy theories, distrusted the system and pursued justice through a jaded eye. He’d often resort to dry, acerbic wisecracks to make his point: “I’m a homicide detective. The only time I wonder why is when they tell me the truth,” went a typical Munch retort.

In a 2016 interview for the website The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, Homicide executive producer Barry Levinson recalled listening to Belzer on The Howard Stern Show and liking him for Munch. “We were looking at some other actors, and when I heard him, I said, ‘Why don’t we find out about Richard Belzer?” Levinson said. “I like the rhythm of the way he talks. And that’s how that happened.”

When Richard Belzer did stand-up on “Late Night With David Letterman,” he always entered to the opening riffs of “Start Me Up” by the Rolling Stones, dancing his way onstage, looking like the life of the party in dark shades. Once he arrived at the microphone, he made a point of engaging with the studio audience in a way you rarely saw on television. More than once, he asked, “You in a good mood?” and waited for a cheer. Then his tone shifted: “Prove it.”With that opening pivot, he turned the relationship between comedian and crowd upside-down. The expectation was now on the people in the seats: Impress me.

Belzer, who died Sunday, is best known for his performances as a detective on TV, but his acting career was built on a signature persona in comedy, as a master of seductive crowd work who set the template for the MC in the early days of the comedy club. Often in jackets and shirts buttoned low, he cut a stylish image, spiky and louche. He could charm with the best of them, but unlike many performers, he didn’t come off as desperate for your approval. He understood that one of the peculiar things about comedy is that the line between irritation and ingratiation could easily blur.

Throughout the 1970s, he ran the show at the buzziest of the New York clubs: Catch a Rising Star, stand-up’s answer to Studio 54. He roasted the crowds while warming them up, quizzing them about where they were from and what they did, establishing rapport and dominance. Long before Dave Chappelle dropped the mic at the end of shows, Belzer regularly did so.

If the crowd wasn’t laughing, he could lay on a guilt trip: “Could you be a little more quiet? Because I’m going to have a nervous breakdown.” And if someone heckled, look out. According to a story from the comic Jonathan Katz, one night someone in the crowd yelled, “Nice jacket!” and Belzer responded that he got it on sale in his mother’s vagina.

Although Carrie's story has been told and retold via various lenses and assumes many tints, the heart of the story remains the same: It is about a girl who experiences the horrors of isolation, where her very existence becomes a quiet act of rebellion. When pushed too far, she brings about literal carnage and bloodbath, too broken to care whether those trapped inside are cruel or kind-hearted.Stephen King, who endorses Brian De Palma's adaptation of his novel, has stated on many occasions that he considers the film's ending more fitting than that of the novel. Those familiar with the novel would agree that while King's ending is suited solely for the purposes of novelistic storytelling, De Palma's highly-stylized, aesthetically-brilliant rendition of the ending works better from a purely cinematic point of view. Carrie's breakdown in the novel is much more deliberate and brutal, as she consciously seeks out her classmates to torment them and makes sure that they are beyond outside help. In fact, the school alone is not the target of her incandescent rage: Carrie makes sure that the whole town suffers her wrath, as she detonates the main gas lines and hunts down her tormentors. As she is on the verge of dying, Sue approaches her, and the two connect on a visceral, psychic level before Carrie breathes her last.

In contrast, De Palma utilizes his telltale split screens to unravel a saga of blood-soaked revenge that seems more guttural and trance-induced than consistently deliberate. Yes, Carrie shuts her classmates inside the burning building, but she does not seek out her bullies after her telekinetic floodgates open. Instead, she is forced to explode the car her tormentors are in to safeguard herself, and has no choice but to crucify Margaret after she stabs her daughter in the back. Heartbroken and betrayed by her own kin, Carrie screams in agony, allowing her power to consume and destroy, and she dies after her house topples under the weight of her trauma-fueled angst.

However, the crowning glory of De Palma's ending is the dream sequence that is the stuff of nightmares: the bloodied hand of a dead girl rising from the grave.

Unlike Stephen King's ending, which settles for an imperfect, yet compassionate mirroring between two complex female characters, Brian De Palma's ending lingers on rage, which comes back to haunt from beyond the grave. Sue, who alternates between bully and sympathizer, ultimately finds herself identifying with Carrie's pain. However, there is no closure for either Carrie or Sue — while Carrie is crushed under the weight of her own pain, Sue is compelled to carry the guilt of Carrie's death, which is now a source of horror to her. Even the way in which Carrie reaches out to Sue in the dream is aggressive, as her hand shoots up from her grave and grabs Sue, pulling her inside the crypt.

Although Sue is not nearly as cruel as the other bullies at school, she ends up shouldering the guilt of Carrie's tragic demise, which fuels bottomless grief and the fear of suffering a similar fate. Despite De Palma's sympathetic portrayal of Carrie, this shock ending paints her as a creature of terror in Sue's mind, who will now be forever haunted by the specter of a girl wronged. Within the ambit of genre tropes and the film's gothic overtones, this sequence works remarkably well, jolting audiences out of a latent state of complacency or the misconception that the worst is truly over.

If anything, this ending is more tragic. Despite attempts by those like Sue to understand and comfort Carrie, she breathes her last feeling cornered and betrayed by the world. Her rage, linked to her personhood and autonomy, momentarily paves the way to liberation in the form of vengeance, but is too much to sustain her. In the end, she remains condemned, even in death, only understood in surreal fragments through channeled feminine grief, and rage.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting that Freddie seems to be getting away from the camera, yet is being tracked by it. I was wondering how you want to establish her relationship to the camera in the film.Chou: It’s totally something that we built into the film, the dance between the camera and the actress. That reflects the dynamic of the character, her constant refusal to be labeled. I decided not to use [over the] shoulder camera. I thought it would be a bit too tautological for filming an agitated character. On the contrary, [we filmed] still shots on her face, but also larger shots with a lot of people. The best example is when she is first meeting her biological family at dinner; there are seven people around the table and it’s like she’s surrounded by people, but it’s only still shots. Then suddenly you can feel [the agitation] because, 20 minutes before, you got to know the fire inside of her and now you can read in her eyes. Even though she doesn’t move, she looks clearly petrified, but something is boiling in her. And I found the tension between [the] stillness of the shots and [the] politeness of the setting reflects a relationship in a traditional Korean family and the boiling fire inside her.

When she feels pressured by people, she starts to become her own filmmaker: transforming other people in the room into extra actors and secondary roles, deciding places and remapping, like at the bar in the beginning. It’s interesting, because it’s someone in the new territory. She’s remapping the restaurant, deciding which people are going to sit and everything like that. She’s not in control in a place that she doesn’t know anything about, so here’s an attempt at taking control. Interestingly, the way of taking control is to create chaos. I was very inspired by Nadav Lapid’s Synonyms and Brian De Palma’s Carlito’s Way for that chaos.

Another scene that’s interesting is the scene where Freddie dances and I’m on the track. I can do this camera movement, the camera can pan a bit and I myself can do the zoom. But then at the same time, I don’t control what she’s actually doing, she’s doing whatever she wants. It becomes this struggle between the two of us.

Filmmaker: Your film has a really interesting relationship to music, in addition to choreography. You have the beginning club scene where it’s on that track and you’re watching Freddie dance. Then you have the other underground clubs and singing at her birthday, which is even more pumped up and fantastical in a way, and even more chaotic. Then you have the last moment where she’s at the piano and she’s completely alone.

Chou: There is an evolution where I play with the cultural identity of the music, as well. At the beginning, you will hear a lot of old vintage Korean songs that symbolize a past Freddie can feel from the texture of the song. You can feel it comes from the ’70s, but because she doesn’t speak the language, it already embodies a contradiction of knowing it’s from the past, but also having no idea what it is. It’s your past that you don’t know. I felt that the first time I went to Cambodia and listened to old Cambodian music.

In the second part, much more of the music is as if she had emancipated herself from her past and decided in some kind of extreme, positive gesture to say, “Hey, you reject me from Korea. I assure you I can be Korean, but I’m not having any link with my family whatsoever. I killed your heritage and now I’m a Korean girl with a Korean boyfriend, a drug fiend and everything.” So the music is very contemporary German techno music, also contemporary Korean electronic music that was composed for the film and shows her state of mind.

The third part is more silence, as if she needed less music. Because music for many is some kind of refuge, for her it is some kind of place that she can jump into and find comfort in when she feels too much pressure. And that’s basically the dancing scene in the first act, when the music is suddenly put on and she dances and there are no other characters in that shot. She dances as if she was inventing her own space, time and temporality. In the last part, there is less music, as if maybe she was ready to listen.

Filmmaker: As opposed to escaping.

Chou: The music becomes not only a refuge, but also a place to express feelings and sentiments when language doesn’t allow you to do it. At the very end, as you say, I think that it is something different. She is ready to be active. This journey may be full of loneliness—being totally alone with herself—so that she can start to feel it’s time to play her own melody.

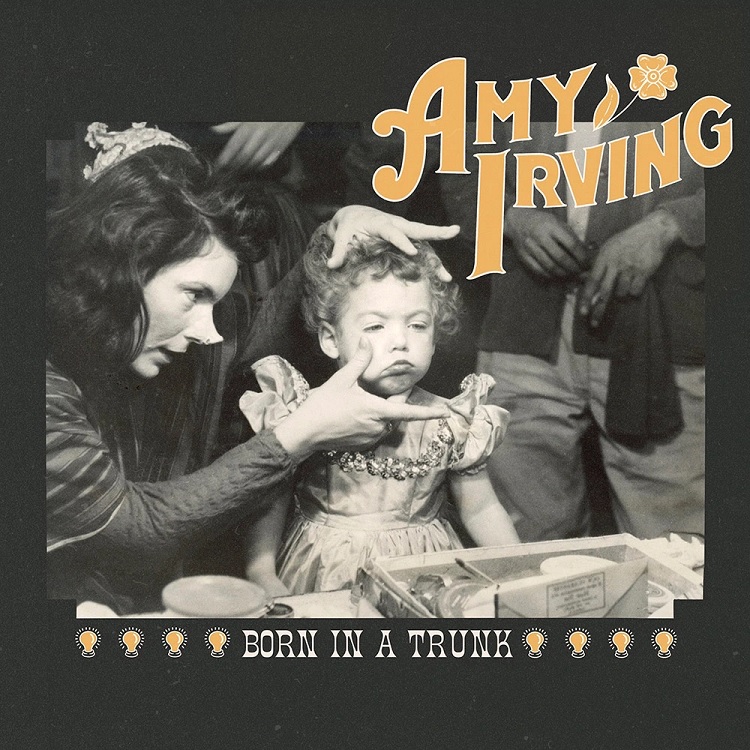

Soon we will have a version of "I Never Dreamed Someone Like You..." sung by Amy Irving, when the track is released on her debut album, Born In A Trunk. According to The Hollywood Reporter's Mesfin Fekadu, Irving's album, "featuring 10 cover songs pulled from her life and career, will be released digitally on April 7. 'Why Don’t You Do Right?' — the first single which Irving sang as Jessica Rabbit in Who Framed Roger Rabbit — will be available on digital platforms on March 3."

Here's more from the Holywood Reporter article:

Born In a Trunk also features Irving covering songs like Pino Donaggio’s “I Never Dreamed” (from Carrie) and Death Cab for Cutie’s “I’ll Follow You Into the Dark,” dedicated to her husband Ken Bowser. Jules David Bartkowski aka Goolis arranged the album and lends vocals to the covers of Jimmy Webb’s “Children’s Song” (from Voices) and Tom Jobim’s “How Insensitive,” featuring Roy Nathanson on saxophone.“Singing makes me happy. I considered myself an actor who could carry a tune, not a singer,” Irving says. “My youngest son, music manager Gabriel Barreto, turned me on to a terrific band he represents: Goolis. He convinced me to cut an album with them. It was so thrilling to step into another world.”

She adds that she chose the 10 songs “from my life’s work, liaisons, marriages, and family.”

“We made the album, then COVID hit,” she continues. “I spent two years working with Celeste Simone, an amazing vocal coach, who taught me how to get up on the stage and sing the songs for the launch. My husband Ken Bowser helped me write intros to the songs. This is my story. It’s been quite a ride. And thanks to Gabe, and Jules and Ken, (and our 2 dogs), the ride continues.”

Willie Nelson heard Irving’s version of his song “I’m Waiting Forever,” reimagined as a galloping calypso, and asked to sing harmonies on the track for the new album. The song, which Nelson recorded for his 1996 album Spirit, was written for Irving and it references their relationship during the production of 1980’s Honeysuckle Rose.

“It is a real pleasure to be singing with my good friend Amy Irving. She has a great band behind her and I look forward to doing more with her,” Nelson tells THR in a statement.

The Born In a Trunk cover art features Irving’s mother, actress Priscilla Pointer, smudging makeup on a 2-and-a-half-year-old Irving. The performer’s father, Jules Irving, was a director and actor.

Irving recorded the album live in the studio with Goolis and eight other band members.

This is a particularly difficult title to speak about, not just because of its content, but how it is worked into the narrative. Instead of spoiling the screening, I’d rather keep my criticism short. However, one should note it is among the most brazenly transphobic narratives in the history of cinema, and its inclusion in this season is primarily to emphasise this point. It cannot be excused, but also cannot be ignored for what it is.

As a fan of De Palma and a trans woman, I’ve always struggled with this film. Over the years, a different portrait of the trans killer Bobbi began to emerge; each new viewing led me to believe there’s more empathy towards her than other critical readings have suggested.The film has some pop psychology gobbledygook about two sexes inhabiting the same body – that both Dr. Elliott and Bobbi, the trans woman, wanted control, and Dr. Elliot barred Bobbi’s transition. Liz asks Bobbi’s gender psychiatrist, Dr. Levy, about this: “You mean when Elliot got turned on, Bobbi took over?” Levy responds, “Yes, it was like Bobbi’s red alert. Elliot’s penis became erect and Bobbi took control, trying to kill anyone that made Elliot masculinely sexual.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was much harder for trans people to be able to transition in America. One would have to fit a very narrow criteria to be approved for the process. The Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, long one of America’s primary trans gatekeeping associations, described it this way in 2001:

During the 1960s and 1970s, clinicians used the term true transsexual. The true transsexual was thought to be a person with a characteristic path of atypical gender identity development that predicted an improved life from a treatment sequence that culminated in genital surgery. True transsexuals were thought to have: 1) cross-gender identifications that were consistently expressed behaviorally in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood; 2) minimal or no sexual arousal to cross-dressing; and 3) no heterosexual interest, relative to their anatomic sex… Belief in the true transsexual concept for males dissipated when it was realized that such patients were rarely encountered, and that some of the original true transsexuals had falsified their histories to make their stories match the earliest theories about the disorder.

An argument can be made that Dr. Elliott, who would have been familiar with these gatekeeping guidelines, would have found it impossible that he could be trans. Most of his profession would have believed this, which could have caused him to try to squash these desires. In fact, Dr. Elliot represents the psychiatric field’s gatekeeping of trans people for not fitting a very narrow definition, which came from the doctor’s own biases over what makes someone a man or a woman.

Does this make Bobbi the secret hero of Dressed to Kill? Not really, as she is still committing murder. To some extent, she represents the way marginalized communities can sometimes misdirect their anger towards other marginalized communities. It’s the patriarchal field of psychology that has prevented her from transitioning, but she instead focuses on the immediate problem: that when she sees attractive women she becomes aroused and this prevents her from reaching her goal of transition. Rather than blame the problem, she blames a symptom of the problem.

Did De Palma set out to hide all this subtext in Dressed to Kill? Probably not, but there are two things about De Palma that aren’t talked about enough. One is that the man does his research. He certainly did not set out to make a film about trans gatekeeping, but he seems to have done enough research to have been aware of its existence – and that impacted where his film went and how he dealt with the (admittedly loose) psychology in it. Without meaning to, he crafted a story that actually tells us important things about the way trans people were treated in the late ‘70s.

The second point is that De Palma, for all the talk of cruelty that surrounds his filmography, is ultimately an empathetic filmmaker.

One of the aspects that will dazzle fans the most is the stunning implementation of Dolby Vision which does not let you down with its depth and nuance. As you might expect, the glorious flames of the finale provide a really nice visual spectacle. Other less obvious elements such as pieces of clothing and some of the environmental elements show their worth. There is also a greater accuracy to the more ruddy colors in some of the interiors of Carrie’s house. The new presentation reaches a level of accuracy and color detail that likely tops the original prints.This disc also delivers some magnificent natural film grain which brings out so much distinct texture in the production design, the special effects and more. This grain resolves well with nothing ever appearing frozen or spiking throughout. This disc executes every environmental change with ease. Even difficult scenes like the steamy shower scene does not turn into a blocky mess. The black levels are pretty strong with no blatant crush present, and white levels never get too hot. Any lingering specks and bits of damage have been eradicated with this latest pass. The makeup effects showcase viscus elements with great clarity which makes the work all the more unsettling. There are a few moments where the encode could have potentially been better optimized, but it is miles away from poor. This is the best the film has looked on home entertainment, and Brian De Palma fans will be thrilled to own one of his top tier works on the format.

Joe Aisenberg, Author Of Studies In The Horror Film: CARRIE provides a very thorough and entertaining commentary track in which he discusses the background and development of the film, the themes of the story, the direction of Brian De Palma, the differences between the movie and the Stephen King source material, the background of some of the performers, anecdotes from the production he gained while researching the book and much more that is well worth a listen.

No idea what will happen, but apparently Warner's distribution agreement for Brian De Palma's Femme Fatale has ended. It's been pulled from digital retailers (excluding those who already bought it), and if you want Shout! Factory's recent Blu-ray of it, might be wise to act fast.