"LET'S GO!"

Updated: Sunday, August 9, 2020 12:56 AM CDT

Post Comment | View Comments (1) | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | August 2020 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

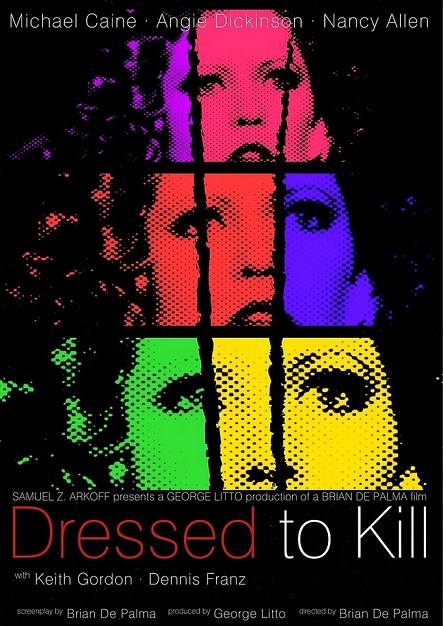

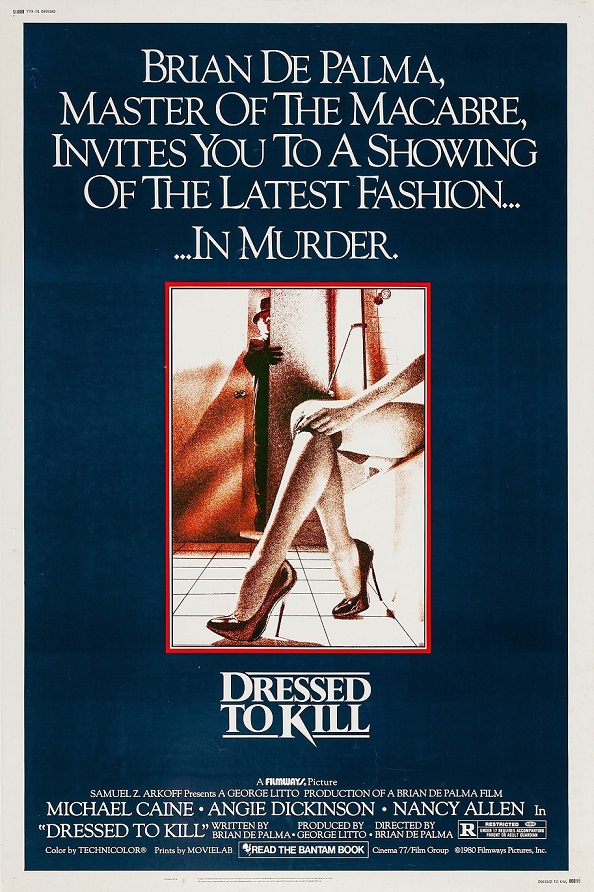

That's just one of the fine moments in this two-hour-and-forty-minute podcast discussion between Gattanella and Hughes of seven Brian De Palma films. The podcast episode runs about the length of De Palma's Scarface, yet that film is not one of the ones included. The films the pair watched and then discussed on this episode are Sisters, Phantom Of The Paradise (Hughes remarks that she admires and appreciates how De Palma made Phantom a tight and lean 90-minute film), Dressed To Kill, Body Double, Raising Cain, Snake Eyes, and Femme Fatale.

During the discussion on Raising Cain, Hughes has a bit of an epiphany:

Korey: I was saying when we first started this, that a lot of De Palma's movies, like Tarantino's movies, are obviously made by someone whose life revolves around movies. Like, I feel like De Palma's life on a personal level, is dominated by the pop culture he's consumed. And one thing I was thinking is that he has all these movies about multiple personalities, and they're all highly entertaining, and not even remotely psychologically plausible. And I think the reason for that is De Palma is filtering multiple personalities through pop culture. So he's not engaging with actual research on this condition in actual people. His movies address how pop culture addresses multiple personality disorder. So I feel like he's riffing on how we as a culture process this concept. Not the actual concept itself.Jack: Well, in the case of Raising Cain, I watched an interview with him, and he said that he had a friend who was a child psychologist, and was trying to do tests about how children respond to this or that, and trauma and stuff like that. And I think in his head, he then bounced off that into what this movie became. So he starts from a very basic place, and then...

Korey: Yeah, I think that's what makes them so melodramatic and heightened, is that he's not telling a story about multiple personalities. He's telling a story about the stories we tell about multiple personalities. And I'm thinking that's what I think really unites his treatment of this concept in Sisters, in Dressed To Kill, in Raising Cain, is he's telling a story about the stories we tell.

Here's the start of Avellino's lengthy post at Mr. Peel's Sardine Liqueur:

Well, we didn’t know this was going to be the future. Stuck like this, away from the people we’ve known and care about. But even now they stay with us as we close our eyes, wishing we were back with them. It’s the naiveté of youth, I suppose, the dream that you grow up and as the future appears the world will grow with you, eventually turning things into that life one dreams of. But the real future, the one we’re going to get, is always closer than we think and those people just get further away. So by the time we actually get there, it’s too late to do anything about it. That’s when we realize there’s no one else around.Brian De Palma’s 2000 film MISSION TO MARS is set in what was then the future. But revisiting this film during its 20th anniversary is not simply about addressing when it opened but how it actually begins in the year 2020, on June 9th to be exact although the preciseness of the date serves little purpose. It’s still a pretty familiar looking future except that people appear to be drinking boxed beer at a crowded barbecue which, boxed beer aside, hasn’t been happening or at least it shouldn’t—I was going to add that we’re also not going to Mars anytime soon but there’s actually a mission happening, go figure, even if there won’t be any humans onboard. Living in this actual time as we are, if you call this living, we already know that the 2020 of this film has little to do with the reality we currently know even if the film doesn’t spend much time on Earth. My main recollections of seeing this film opening night way back in March of that year at the El Capitan on Hollywood Blvd. are that the packed house violently booed when the end credits rolled and someone threw what looked like a Snapple bottle at the screen. But time changes things. For one, this is a film where a character gets marooned all alone and who the hell knew back then that the very idea of isolation would turn out to have the most to do with what life in 2020 really is. Like many films that have been loudly rejected on opening night, MISSION TO MARS is more interesting than that initial response indicated and even though it does still have more than a few issues, it’s a film striving to be about hope and connection in a way that makes me think a little more fondly about it these days. There’s a lot to figure out right now about the way things are going and even if there aren’t any real answers in the film I’m watching, there’s always the dream that maybe something can still be found there.

As the first ever crew on the surface of Mars explores the red planet, they discover the possibility of water which would allow for earth colonization. But when they try to investigate, the entire team except for Commander Luke Graham (Don Cheadle) is wiped out by a mysterious vortex of massive size leaving the lone astronaut remaining stranded there. When news of this reaches the World Space Station via a message that indicates Luke is still alive, plans for the next ship for Mars are changed to turn it into a rescue mission which will include Commander Woody Blake (Tim Robbins), wife Terri (Connie Nielsen), Phil Ohlmeyer (Jerry O’Connell) and Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise), who gave up his own shot at commanding Mars One when his wife Maggie (Kim Delaney) fell ill and soon died. But months later when their ship begins to orbit Mars things immediately don’t go as planned and once the team reaches the ground to search for Luke, they soon discover the existence of a massive stone face which may lead to the answer of what sort of life once existed on that planet and what may have really happened to it.

For one thing, it’s definitely the second best Brian De Palma film with the word “Mission” in the title but this is of minor importance. Even after all this time MISSION TO MARS is still a tough one to figure out, a film which on the surface doesn’t seem to be anything other than a showcase for spectacular digital effects but somewhere deep down feels like it has other goals in mind that it hasn’t entirely worked out. Maybe it wants to be more of an interior journey into outer space but even with several big names in the cast the characters are never interesting enough to warrant this approach so what’s left becomes the focus on those effects and the way De Palma builds his own visual methods around them. Right from the very first moment as the title flashes onscreen a rocket blasts off, only to be revealed as a toy in a suburban backyard giving the impression the film wants to play with our expectations, finding a way to turn kid stuff into the adult regret of lost dreams and back again, to understand what the dream in those toys meant in the first place. It’s an idea that doesn’t feel entirely formed and the film is forced to pay more attention to all that hardware while still looking for ways around all the expected tropes, like how in place of the expected spectacular launch sequence is a simple transition to the surface of Mars done with a cut from a playful footprint in a backyard on Earth. This is an attempt at hard science fiction which at times seems more interested in finding unexpected ways to tell the story rather than acclimating us to the drama at hand and plays at such a distance that it’s a little too easy to check out early on. There’s no mission control populated with familiar character actors, no cutaways to worried loved ones back home, no bogus conflict between the astronauts played by big names and even an early sequence involving cross cutting that plays with notions of time within the narrative for reasons that still seem a little hazy.

A few plot points, like how Cheadle’s command will presumably be joined at a later date by Mars II commanded by Robbins, seem vague in the way they’re casually discussed but I’m not sure it matters and I’m not sure the director really cares about making such generalities clear. Complicated exposition gets doled out in a way that hasn’t taken into account what anyone watching the film doesn’t know so not enough of it registers, lost to whatever De Palma is actually interested in focusing on. Even when the film opens with one of his patented endless Steadicam shots it’s not about the technology surrounding a Mars launch but the simple act of the astronauts socializing at a farewell barbecue, giving us more info about the relationships than the actual mission which is fine but the mundane setting doesn’t seem to warrant such a complex visual approach (which features a cut partway through as if a decision was made in editing to rush things along) and it also makes the film feel unexpectedly small with the interactions never registering all that much as the camera swirls around them. There’s so little drama in the friendships of the main characters which means right from the start we’re facing a Brian De Palma film where everyone gets along, no ominous foreshadowing in the air, so earnest that the scenes barely seem about anything.

The way the writing credits read (screenplay by Jim Thomas and John Thomas & Graham Yost, story by Lowell Cannon & Jim Thomas and John Thomas) along with the very nature of the project (presumably inspired by the Disneyland ride that closed back in ’92 but it has the Touchstone Pictures logo) one imagines many, many drafts of various scripts written but the story still feels either not quite smoothed over or maybe had whole sections deleted for whatever reason. One major plot point is even relayed via news delivered remotely at another location and there’s something to be said about how the film seems more interested in dwelling for a long moment on the sight of Armin Mueller-Stahl silently drinking a cup of coffee than the spectacular landing we didn’t get to see. But the question is are there really plot points to this film or just several specific events leading up to the final revelation. So much of what appeals about films directed by Brian De Palma more than the necessities of story structure is his portrayal of the madness that surrounds the main characters as they try to make sense of this increasingly insane world while the plot happens around them. The characters in this film are all good and pure, which makes sense since they’re astronauts, but the earnestness doesn’t feel all that fleshed out as if he doesn’t quite know how to make it ever seem genuine. They can each be described simply via who means the most to them, nothing more; Woody and Terri are the happy couple, Jim is sad because his wife died, Luke misses his son back on Earth and Phil is the joker who constructs the DNA of his dream woman using M&M’s in zero gravity. There’s no real conflict between the characters at all beyond how to address whatever any given immediate issue might be, saying things like “Let’s work the problem” as they get to it, all of them so idealized as heroes that there isn’t much else to them beyond the perfection. These are the types who normally get sacrificed, if not totally destroyed, in the cruel world of De Palma films so maybe in being forced to portray people without flaws it removes all the fun and doesn’t replace it with anything particularly interesting.

This has never been a director known for showing much interest in healthy relationships between men and women (maybe with the exception of Kevin Costner as Eliot Ness and Patricia Clarkson as “Ness’ Wife” in THE UNTOUCHABLES) which makes it feel like there’s not much to portray here beyond the simple idealization. Tim Robins and Connie Nielsen are played as being totally devoted to each other, such a mirror image of Gary Sinise and his late wife played in flashback by Kim Delaney that it almost feels a little confusing as if husband-wife missions have somehow become a NASA requirement in the future. But even if the perfection plays like a neon sign that something bad has to happen, this is still a rare Brian De Palma film with next to no cynicism, no irony or real sense of the fates conspiring against all the goodness in the universe. Even when a sacrifice has to be made, even when an American flag is planted upon arrival at the new planet, it seems to insist on holding onto some kind of optimism so the movie is never embarrassed by its own inherent dorkiness coming out of the science fiction technobabble or how much these people love each other as if it wants to actually believe in this dream of everything being ok.

Meanwhile, there have been quite a few podcasts focusing on Dressed To Kill of late. Two more podcasts that popped up this week mention "plot holes" and things like that, but let's face it... although these podasts produce some valuable insights into Dressed To Kill, they are full of "plot holes" of their own-- it can be tough to listen sometimes without wanting to jump in with a bit of info that the participants seem to have missed. At The Unaffiliated Critic, Michael G. McDunnah, who, for context, doesn't like Casualties Of War nor Femme Fatale, chooses to watch and discuss Dressed To Kill with his wife, who is known as "The Unenthusiastic Critic," which is the name of their podcast. It's a fun discussion, as you might imagine.

The "Sordid Cinema Podcast" at Goomba Stomp features some insightful discussion, as long as you don't get too squirmy listening to the two participants talk about how Michael Caine gives a supposedly boring performance, how the whole character of Betty Luce is "unnecessary" and could have been taken out of the script, and also some confusion about exactly where the climactic dream sequence begins (and then listening to one of them talk about how it could have been "fixed" -- when really, it sounds like he just needs to go back and watch it again). As I said, despite these sort of "plot holes" in the podcasts, there are interesting discussions and insights.

"As a fan of De Palma and a trans woman," Crets states, "I’ve always struggled with this film. Over the years, a different portrait of the trans killer Bobbi began to emerge; each new viewing led me to believe there’s more empathy towards her than other critical readings have suggested." Crets feels that while "the film has some pop psychology gobbledygook about two sexes inhabiting the same body," De Palma nevertheless did his research. "Without meaning to, he crafted a story that actually tells us important things about the way trans people were treated in the late ‘70s."

Here's an excerpt from Crets' article:

In his 2015 Daily Beast piece on the Criterion release, writer Keith Phipps quotes trans woman film critic Alice Stoehr as noting, “Elliott’s pathology—‘opposite sexes inhabiting the same body’—bears minimal resemblance to the experiences of actual trans women. Instead, it reads as a conflation of trans identity with dissociative identity disorder. At its most hostile, Dressed To Kill suggests that trans women are dangerous, unstable, and confused. Whereas in Carrie, De Palma found truth by telling his monster’s story, here the monster is incomprehensible and alien.” This was one of the nicer quotes I found about the movie from other trans women, but you get the idea.As a fan of De Palma and a trans woman, I’ve always struggled with this film. Over the years, a different portrait of the trans killer Bobbi began to emerge; each new viewing led me to believe there’s more empathy towards her than other critical readings have suggested.

The film has some pop psychology gobbledygook about two sexes inhabiting the same body – that both Dr. Elliott and Bobbi, the trans woman, wanted control, and Dr. Elliot barred Bobbi’s transition. Liz asks Bobbi’s gender psychiatrist, Dr. Levy, about this: “You mean when Elliot got turned on, Bobbi took over?” Levy responds, “Yes, it was like Bobbi’s red alert. Elliot’s penis became erect and Bobbi took control, trying to kill anyone that made Elliot masculinely sexual.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was much harder for trans people to be able to transition in America. One would have to fit a very narrow criteria to be approved for the process. The Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, long one of America’s primary trans gatekeeping associations, described it this way in 2001:

During the 1960s and 1970s, clinicians used the term true transsexual. The true transsexual was thought to be a person with a characteristic path of atypical gender identity development that predicted an improved life from a treatment sequence that culminated in genital surgery. True transsexuals were thought to have: 1) cross-gender identifications that were consistently expressed behaviorally in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood; 2) minimal or no sexual arousal to cross-dressing; and 3) no heterosexual interest, relative to their anatomic sex… Belief in the true transsexual concept for males dissipated when it was realized that such patients were rarely encountered, and that some of the original true transsexuals had falsified their histories to make their stories match the earliest theories about the disorder.

An argument can be made that Dr. Elliott, who would have been familiar with these gatekeeping guidelines, would have found it impossible that he could be trans. Most of his profession would have believed this, which could have caused him to try to squash these desires. In fact, Dr. Elliot represents the psychiatric field’s gatekeeping of trans people for not fitting a very narrow definition, which came from the doctor’s own biases over what makes someone a man or a woman.

Does this make Bobbi the secret hero of Dressed to Kill? Not really, as she is still committing murder. To some extent, she represents the way marginalized communities can sometimes misdirect their anger towards other marginalized communities. It’s the patriarchal field of psychology that has prevented her from transitioning, but she instead focuses on the immediate problem: that when she sees attractive women she becomes aroused and this prevents her from reaching her goal of transition. Rather than blame the problem, she blames a symptom of the problem.

Did De Palma set out to hide all this subtext in Dressed to Kill? Probably not, but there are two things about De Palma that aren’t talked about enough. One is that the man does his research. He certainly did not set out to make a film about trans gatekeeping, but he seems to have done enough research to have been aware of its existence – and that impacted where his film went and how he dealt with the (admittedly loose) psychology in it. Without meaning to, he crafted a story that actually tells us important things about the way trans people were treated in the late ‘70s.

The second point is that De Palma, for all the talk of cruelty that surrounds his filmography, is ultimately an empathetic filmmaker.

More details on the Donaggio cues used in Homecoming

Homecoming borrows from Donaggio's score for Dressed To Kill

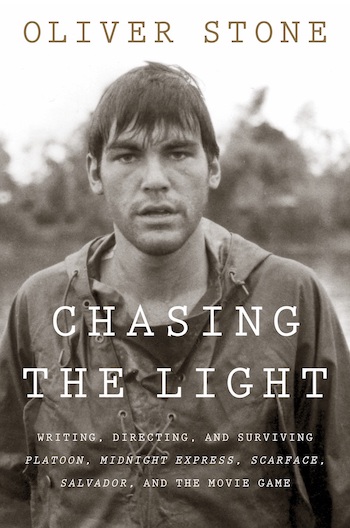

"I saw [Scarface] for the first time in a packed theater on Broadway with a paying audience, mostly Latino and black, which gave the film street cred, and right there I knew it was a better movie than the film crowd thought — and that it would last." So says Oliver Stone in an exclusive excerpt today at MovieMaker "adapted" from Stone's new memoir, Chasing The Light, out today. "I knew it from riding the New York subways," Stone continues in the excerpt. "I knew it from hearing people talk on the street. I knew it from the people who shouted back at the film, who’d repeat the lines and laugh on the playgrounds and in the parks. These people knew it in their gut. The War on Drugs was bullshit from beginning to end, a fraud sending them to prison in massive numbers. These people knew that Tony Montana had a code of honor of his own, and as fucked up as he was, he was true to his nature till that end. He was a free man. I heard from his family years later that Pablo Escobar, the emerging king of cocaine at that time down in Colombia, adored it and screened it many times. And within a couple of years, the white folks who knew the drug world came to appreciate it. Michael Mann plunged right in with the TV series Miami Vice (1984). He saw the power of it, acknowledged it to me, and cashed in more than we ever did. By the time I made Wall Street in 1987, the young white guys down there were quoting it back to me at viewing parties.

"I saw [Scarface] for the first time in a packed theater on Broadway with a paying audience, mostly Latino and black, which gave the film street cred, and right there I knew it was a better movie than the film crowd thought — and that it would last." So says Oliver Stone in an exclusive excerpt today at MovieMaker "adapted" from Stone's new memoir, Chasing The Light, out today. "I knew it from riding the New York subways," Stone continues in the excerpt. "I knew it from hearing people talk on the street. I knew it from the people who shouted back at the film, who’d repeat the lines and laugh on the playgrounds and in the parks. These people knew it in their gut. The War on Drugs was bullshit from beginning to end, a fraud sending them to prison in massive numbers. These people knew that Tony Montana had a code of honor of his own, and as fucked up as he was, he was true to his nature till that end. He was a free man. I heard from his family years later that Pablo Escobar, the emerging king of cocaine at that time down in Colombia, adored it and screened it many times. And within a couple of years, the white folks who knew the drug world came to appreciate it. Michael Mann plunged right in with the TV series Miami Vice (1984). He saw the power of it, acknowledged it to me, and cashed in more than we ever did. By the time I made Wall Street in 1987, the young white guys down there were quoting it back to me at viewing parties. "The film would live on strangely in my life, an inside-the-park home run, an entrée to a certain wild, transgressive sector of our society. For years, people would congratulate me and quote me lines from it. Gangsters and their ilk would buy me drinks, champagne, in such faraway places as Egypt, Russia, Cambodia. I could’ve made a great deal of money by accepting a sequel, but my 'gangster' thoughts were ready to explode into the new milieu of Wall Street.

"Scarface was not The Godfather. It lacked the family and the sense of a tragic arc. But it was a juicy, crude opera of a drug dealer’s life set across a slimeball American materialism flowering in South Florida, the madness of a dream that always wants “more … more … and even more.” Greed was indeed good. The ’80s had arrived."

The above is only the last part of the excerpt-- read the full excerpt at MovieMaker. Here's the MovieMaker intro:

Before Scarface launched a boatload of T-shirts, posters, memes, and dubious imitations of Al Pacino’s cocainized Tony Montana, the film, written by Oliver Stone, was just a movie in trouble.In this excerpt from his new memoir Chasing the Light: Writing, Directing, and Surviving Platoon, Midnight Express, Scarface, Salvador, and The Movie Game, Oliver Stone recalls how he found himself caught between Pacino, Scarface director Brian De Palma, and Scarface producer Marty Bregman after a rough-cut screening of the movie that would soon become beloved as a classic of ’80s excess. Everything would work out, of course—in just a few years, Oliver Stone won the Academy Award for Best Director for Platoon, which also won Best Picture. Pacino and Bregman continued their long professional collaboration with Sea of Love and another De Palma film, Carlito’s Way.

De Palma’s next film after Scarface was Body Double, another very ’80s, freakishly watchable film that wasn’t an immediate success but has earned a ravenous cult following. And soon after he made another Al Capone-indebted gangster epic (one that got more initial respect than Scarface), The Untouchables. Stone eventually reunited with Pacino, this time as a director, in the adrenalized but surprisingly affectionate Any Given Sunday, another Miami-set tale of machismo, greed, and desperation.