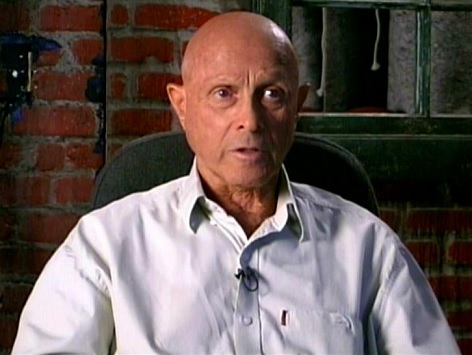

RICHARD H. KLINE DIES AT 91

CINEMATOGRAPHER ON 'THE FURY' & 'THE BOSTON STRANGLER' ENJOYED VARIETY IN HIS WORK Richard H. Kline

Richard H. Kline, cinematographer on

Brian De Palma's

The Fury, died of natural causes Tuesday, according to

The Hollywood Reporter. He was 91.

Kline was nominated for an Academy Award for his work on

Josh Logan's

Camelot (1967), a musical starring

Vanessa Redgrave and

Richard Harris. For the wedding scene, Kline decided to use only candlelight. It was a challenge for Kline, even after having to prove to nervous producers that the candlelight would read on film.

Kline worked on several films with Richard Fleischer, beginning with The Boston Strangler (1968), which became influential for its use of split-screen. Kline worked with Fleischer on four more films: Soylent Green (1973), The Don Is Dead (1973), Mr. Majestyk (1974) and Mandingo (1975).

Kline was nominated for a second Oscar for his work on the 1976 remake of King Kong. Other credits (among many) include Karel Reisz' Who'll Stop the Rain (1978), Jim McBride's remake of Breathless (1983), Robert Wise's Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and Lawrence Kasdan's Body Heat.

Kline chose Bernardo Bertolucci's The Conformist to show to the crew of Body Heat. (Kasdan had asked everyone to choose one film to screen, in order to establish common ground among the crew.)

"I believe in variety," Kline once explained to students at the American Film Institute. "I think there are some brilliantly photographed films, but there’s a sameness. Each scene may be a work of art, but you start seeing it repeated over and over and over again. I find that Bertolucci is a master at variation, a variety of looks within a single film. I try to do that in my work as well."

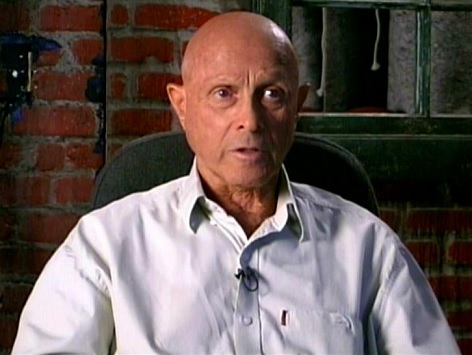

In 2013, Kline rewatched The Fury in preparation for a Film Factory interview, which was used as a supplement on several European DVD/Blu-ray editions of the film. Here's a brief excerpt from that interview:

This is the only time that I've worked with Brian De Palma, and it was a great pleasure, I must say. And we started filming in Chicago, which is a great visual city. It's a unique city. And we have a variety of looks. The Fury, to me, looking back now 35 years, whatever it was, in re-running it to prepare for this interview, I’m going to put it at probably one of the best pictures I’ve ever made, technically—you’re never aware of the technique. With the reality, the freshness of it. Seeing it again, it reminded me of how good it is. It really… De Palma did a terrific job of directing it, without a doubt.

When I was first asked to do the film, I was in Mexico doing a film with a very fine director, also-- Karel Reisz-- and my agent called me to tell me that Brian De Palma would like me to do a film with him when I complete the film I was doing in Mexico. And I asked Karel Reisz, I said, I don't know De Palma, I know of him, what do you think? 'He's a very talented director,' he said, 'take it, take it, take it.' And that came from, I think, one of the most gifted directors ever. And a wonderful person.

So I arrived maybe a month later, when I finished the picture in Mexico, and met De Palma in his office. And every wall was loaded with the sketches-- his... like a comic book, in a way, he would do it. He had pre-designed the whole picture. And I said, well, this is going to be a breeze, you've got everything lined up. And he said, 'Oh, yeah." Anyway, I was impressed with him. And then when we started the picture, he would say, 'Here's the shot." Well, it was easy to do with the camera, you know, we would put the camera in the position that would capture the sketch, and I would light it.

And I said, 'Something is bothering me here.' And I brought Brian to the side, and I said, 'Brian, you're not rehearsing anything before we film.' And it's a way of working-- I haven't worked this way before. I've always found something interesting comes from a rehearsal. And, it either comes from the actor, it comes from seeing the actors doing it, that you see-- things happen that you just can't put on paper all the time. Because first of all, the script-- I was working from a script that was all white pages. As we're filming, there's adjustments made in the script. Dialogue, whatever it is, a lot of things. And the pages come in different colors-- they start with blue, and then yellow, then gold and whatnot. I said, 'I've never worked on a picture that had all white pages.'

And he listened and everything, he was attentive. And I talked him into rehearsing. And he bought it. And he found value in rehearsing that deviated from the sketches. And I think after a week, we didn't see the sketches anymore. He was at rehearsal, we would... I do it with almost every director who doesn't want to work that way, talk them into it-- I've been very lucky that way. We would have the crew doing the scene, during the development of the scene, we'd get everybody off the set, and we'd have coffee, read the paper, whatever it was, so no interruptions or disturbances, so the actors can be themselves and not worry about somebody watching them. And he found that to be very valuable. And we did get very good things, and that's the way we operated.

But he would sit there-- he was... Brian would be, while I'm lighting and whatever, my part, he would sit there, thinking things, always deep in thought. And I respected that of him, I only consulted him when I had to, and, you know, give an opinion, whatever, or we'd joke about something, whatever.

Sebastian Gutierrez's Elizabeth Harvest was released a couple of weeks ago, and is described by

Sebastian Gutierrez's Elizabeth Harvest was released a couple of weeks ago, and is described by  Soraya Secci, an actress from Cagliari, tells

Soraya Secci, an actress from Cagliari, tells  Jane Levy, currently appearing on Hulu's Stephen King-based anthology series Castle Rock, was interviewed a few days ago by

Jane Levy, currently appearing on Hulu's Stephen King-based anthology series Castle Rock, was interviewed a few days ago by

Richard H. Kline, cinematographer on Brian De Palma's The Fury, died of natural causes Tuesday, according to

Richard H. Kline, cinematographer on Brian De Palma's The Fury, died of natural causes Tuesday, according to