AND KEEP THE JOKES COMING

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | July 2018 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Mission Impossible is an unusual film franchise. It's spanned more than 22 years and five directors, each bringing his own distinctive touch to Tom Cruise's increasingly over-the-top escapades. Brian De Palma's 1996 film, which kicked off the series, hearkens back to classic '70s conspiracy thrillers while John Woo's Mission Impossible 2 is pure '90s action blockbuster excess, complete with dueling motorcycles, elaborate shootouts and his signature doves.To prime audiences for the next film, Fallout, Paramount re-released the entire Mission Impossible series on 4K Blu-ray last month. The new discs are not only a huge upgrade for cinephiles but also a fascinating glimpse at how studios can revive older films for the 4K/HDR era.

"In terms of any re-transfers or remastering that we are doing for our HDR releases, we will go back to the highest resolution source available," Kirsten Pielstick, manager of Paramount's digital-mastering group, said in an interview. In the case of Mission Impossible 1 and 2, that involved scanning the original 35mm negatives in 4K/16-bit. As you'd expect, the studio tries to get the original artists involved with any remasters, especially with something like HDR, which allows for higher brightness and more-nuanced black levels.

Pielstick worked with the director of photography (DP) for the first Mission Impossible film, Stephen H. Burum, to make sure its noir-like palette stayed intact. Unfortunately, the studio couldn't get Woo to visit for the second film's restoration, but Pielstick said they had multiple conversations with him about how it was being handled. Though they're very different movies, they each show off the benefits of HDR in different ways.

Watching the first film on 4K Blu-ray was like seeing it for the first time. I could make out more details in the dark alleys of Prague and in the infamous aquarium-explosion set piece. Mission Impossible 2's bombastic explosions and vehicle chases, on the other hand, almost seemed three-dimensional thanks to HDR's enhanced brightness.

"Our mastering philosophy here is always to work directly with the talent whenever possible and use the new technology to enhance the movie but always stay true to the intent of the movie," Pielstick said. "You're not going to want to make things brighter just because you can, if it's not the intent of how you were supposed to see things."When working with directors and DPs, Pielstick said some are more aggressive than others during the restoration process. But if it can't get the original talent involved, Paramount's mastering group relies on the original film as a reference and works together with studio colorists for every project. "[A remaster] should be what they were seeing through the lens of the camera at the time they were shooting it," she said.

"But on the other hand, we've also found times where there's a look where things were previously blown out, intentionally," Pielstick said. "We have to go in and work to get things brought down and blown out in this world. It's really hard to blow out any whites when you have 4,000 nits available to you [with HDR]. So there's a different approach to some of those to, again, maintain intent.

"You also have to remember that we're not putting in anything that didn't exist on the film [for HD remasters]," Pielstick added. "It was always there; we just didn't have the ability to see it. So we're not adding anything new, we're not doing anything to increase those. We're just able to look at the negative in a much clearer way than we ever could before."

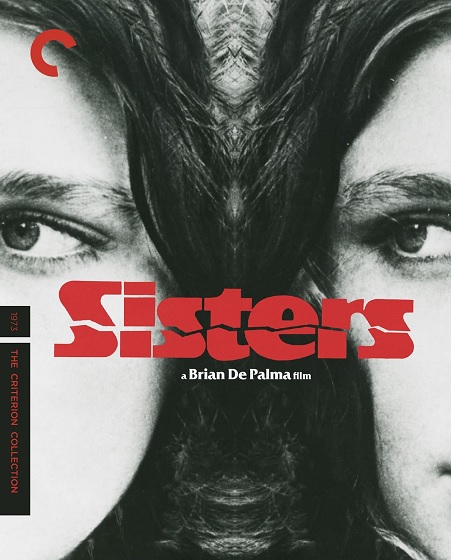

The Criterion Collection today announced that it will release a new edition (on Blu-ray and DVD) of Brian De Palma's Sisters on October 23, 2018. Criterion had previously released Sisters on DVD in 2000. The new release features a cover by Jay Shaw. Not all of the special features that will be included have been worked out yet (the list, presented below, states, "More!"), but here is what Criterion lists for now:

The Criterion Collection today announced that it will release a new edition (on Blu-ray and DVD) of Brian De Palma's Sisters on October 23, 2018. Criterion had previously released Sisters on DVD in 2000. The new release features a cover by Jay Shaw. Not all of the special features that will be included have been worked out yet (the list, presented below, states, "More!"), but here is what Criterion lists for now:Special FeaturesNew 4K digital restoration, approved by director Brian De Palma, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray

New interview with actor Jennifer Salt

Interviews from 2004 with De Palma, actors William Finley and Charles Durning, and producer Edward R. Pressman

Audio from a 1973 discussion with De Palma at the AFI

Appearance from 1970 by actor Margot Kidder on The Dick Cavett Show

More!

PLUS: An essay by critic Carrie Rickey, excerpts from a 1973 interview with De Palma on the making of the film, and a 1973 article by De Palma on working with composer Bernard Hermann

New cover by Jay Shaw

In 2009, Tony Dayoub at Cinema Viewfinder hosted a Brian De Palma Blog-A-Thon, which Carrie Rickey wrote about in her "Flickgrrl" column for the Philadelphia Inquirer. Here's her brief summary of De Palma's career up to that point:

Few filmmakers polarize filmlovers like De Palma, whose love-'em-or-hate'em features include the marrow-chilling Sisters (1972) and the definitive high-school horror flick Carrie (1976). The director, a bearded barrel of a man, grew up near Philadelphia's Rittenhouse Square (his father was the head of surgery at Jefferson Hospital) and attended Friends Central. De Palma directed Blow Out (1981), one of the best movies made in Philly, the addictively enjoyable Scarface (1983), the provocative peeping-Tomcat Body Double (1984), that slickly entertaining The Untouchables (1987) one of the most compelling among Vietnam films, Casualties of War (1989) and the stylish Mission: Impossible (1996). Though he hasn't scored a maintream hit since then, Femme Fatale (2002) is one of my guilty pleasures, an impossibly sexy dreamscape with Rebecca Romijn-Stamos and Antonio Banderas.De Palma does not so much explore as present the connection between sex and power (and vice-versa), which in his films is often linked by an umbilicus of blood. (As Tony Montana, hero of the Oliver Stone-scripted Scarface, put it: First you get the money, then you get the power, then you get the women.") Another persistent theme is that of a man unable to save a woman in jeopardy.

The naked violence and sexuality of De Palma's films have made him a controversy magnet. During the 1980s some social critic observed that every time he made a movie he lowered the national IQ by 10 points. Since there are so few filmmakers with such swoony style, I'm inclined to forgive him for a lack of substance. You will not, however, hear me defending the indefensible The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) or Mission to Mars (2000), ravishing, but indecipherable.

"Brian De Palma's Get To Know Your Rabbit was made three years ago," Canby begins in his review, "yet it did not arrive in New York until Wednesday, and then with less advance word than usually accompanies the opening of a Broadway shoe store. This casual treatment is unfortunate since De Palma (Greetings, Hi, Mom) is a very funny filmmaker. He's most funny, so far, anyway, when he's most anarchic, and Get To Know Your Rabbit, though somewhat inhibited by conventional form, has enough hilarious loose ends and sidetracks to liberate the film from its form."

TFH's Joe Dante, meanwhile, posted his own tweet today: "Have you gotten to know #GetToKnowYourRabbit lately? Director #BrianDePalma’s surreal comedy, starring #TomSmothers and #OrsonWelles, was his first studio film. TFH Guru @Karaszewski has your full primer on the flick as Brian De Palma Week concludes!"

It seemed to me that the Weinstein affair was an excellent field for a psychological horror film called Predator. It will not be a realistic movie, far from it. I followed this story and the hashtag MeToo on television and in the newspapers. It gave me the idea of making an extremely terrifying movie.

Yes, but it's more and more difficult. Even for my film about Harvey Weinstein, I could not get enough funding in the United States. They are terrified by the idea of producing something so close to their own industry, they don't want to know anything about it, certainly not to see it on the big screen. It's unfortunate. My films that criticized US foreign policy have not been well received and have only found their audience in Europe. I often make films about power and corruption, whether in Phantom Of The Paradise or Scarface, because it fascinates me. Today, there is more and more paranoia, some people isolate themselves from reality; we live in a time when this is happening with our president, Donald Trump.

Carrie was turned down by every studio because the male executives were put off by the now-iconic shower scene where Carrie has her first menstruation. But it got made because Marcia Nasatir, the first woman production executive, believed in the book, and in Brian De Palma.Sissy Spacek was a method actor. She surrounded herself with religious icons, studied the Bible, and imagined being stoned to death for her sins. Piper Laurie had been out of the business for 15 years, and nonetheless, again, Marcia Nasatir insisted that she was perfect for the part.

De Palma's technical skills brought a visual sophistication to the high school horror genre. Split screens, diopters for deep focus, and spinning actors, lights, and camera for the celestial prom dance. There are heavily orchestrated crane shots inspired by Hitchcock, and the mother's death by flying cutlery is an homage to Kurosawa's Throne Of Blood. But battles with cowardly studio execs continued: "Pig's blood? Does it have to be pig's blood, Brian? How about confetti?"

On a $1.8 million dollar budget, it grossed $33 million. Roger Ebert wrote that it was "absolutely spellbinding." Every male UA exec claimed it was their project. Marcia Nasatir went on to develop Coming Home and Rocky. Then, there is the last scare-- Carrie's ultimate revenge. Sissy Spacek insisted that it be her hand, and she'd be buried in the grave. The audience is still screaming.

Wagner Moura has been cast as the lead in Brian De Palma's Sweet Vengeance, according to O Globo's Lauro Jardim, who posted the news today. Moura is known for his role as Pablo Escobar on the Netflix series Narcos, as well as for Elite Squad, which was directed by José Padilha, who is also a producer of Narcos and directed the first two episodes of that series. Sweet Vengeance, which is being produced by Brazilian Rodrigo Teixeira, will be set in the U.S., but will be filmed in Montevideo, Uruguay. According to Jardim, the original screenplay is written by De Palma, and the film will begin shooting in January 2019. Previous reports had suggested a ten-week shoot that would begin in November.

Wagner Moura has been cast as the lead in Brian De Palma's Sweet Vengeance, according to O Globo's Lauro Jardim, who posted the news today. Moura is known for his role as Pablo Escobar on the Netflix series Narcos, as well as for Elite Squad, which was directed by José Padilha, who is also a producer of Narcos and directed the first two episodes of that series. Sweet Vengeance, which is being produced by Brazilian Rodrigo Teixeira, will be set in the U.S., but will be filmed in Montevideo, Uruguay. According to Jardim, the original screenplay is written by De Palma, and the film will begin shooting in January 2019. Previous reports had suggested a ten-week shoot that would begin in November.Previously:

Alcaine to shoot De Palma's Sweet Vengeance

Sweet Vengeance to frontline two international leads, male & female

De Palma designing complex drone shot for new film

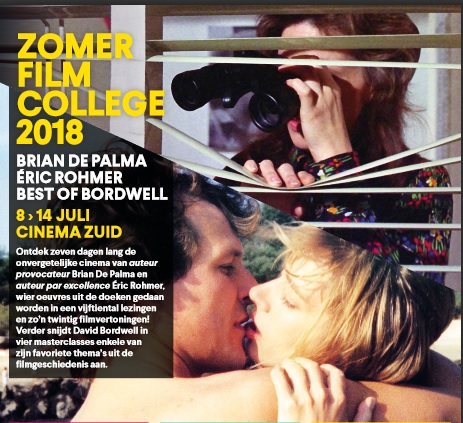

Last March, I posted about the upcoming Summer Film School Rotterdam, running July 18-22, with lectures and screenings of five Brian De Palma features all presented by Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin.

Last March, I posted about the upcoming Summer Film School Rotterdam, running July 18-22, with lectures and screenings of five Brian De Palma features all presented by Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin.July 9

Sisters (1972, 93’, 35mm) - De Palma’s Beginnings: Art, Music and the Counter-Culture

Carlito's Way (1993, 144', 35mm) - Introduction by Adrian Martin & Cristina Álvarez LópezJuly 10

Dressed To Kill (1980, 105', 35mm) - The Hitchcockian Model and its VariationsJuly 11

Blow Out (1981, 107’, 35mm) - Vision and Sound: The Complex MachineJuly 12

Raising Cain (1992, 92', 35mm) - Story, Identity and Point-of-ViewJuly 13

Femme Fatale (2002, 115', 35mm) — The Dream-Film: De Palma’s TestamentJuly 14

Passion (2012, 102', 35mm) — The Langian Model: Narrative and Society as Trap

Scarface (1983, 169’, 35mm)

Summer Film School Rotterdam

July 18 — De Palma’s Beginnings: Art, Music and the Counter-Culture

Phantom of the Paradise (1974, 92’, DCP)

July 19 — The Hitchcockian Model and its Variations

Obsession (1976, 98’, DCP)

July 20 — Vision and Sound: The Complex Machine

Carrie (1976, 98’, DCP)

July 21 — Story, Identity and Point-of-View

Body Double (1984, 114’, DCP)

July 22 — The Langian Model: Narrative and Society as Trap

The Black Dahlia (2006, 121’, 35mm)

HOW DIGITAL HAS CHANGED THE WAY DIRECTORS WORK

In the interview, Alcaine mentions Sweet Vengeance while discussing how digital technology has changed his work:

Most of all, the digital revolution has changed the way that directors work. There's a famous memo in which David O. Selznick warned King Vidor not to do more than five takes of each shot while filming Duel in the Sun. Today, thanks to the low cost of digital technology, one can shoot countless takes, and with several cameras! Many movies are shot with three, four, or even eight cameras. That destroys any notion of the director's point of view. There are still directors who shoot with only one camera, such as Asghar, Pedro, or Brian De Palma, with whom I'll shoot Sweet Vengeance in October. But there are directors who have no idea what they're going to edit while they're shooting. They use three or four cameras and the end result looks like a television broadcast.

Rather than national identity, I was focused on doing justice to the narrative complexity and the choral structure of the film through the image, something that is not very common in contemporary cinema. Many film directors today come from the advertising or television worlds, and when they shoot, they're thinking in small screen terms. They tend to employ open diaphragms that drive the viewer's attention toward one character, leaving everything else out of focus. The resulting image can be very beautiful, with an impressionistic touch, but for me that means stealing something from the viewer. Cinema ahould invite the audience to embark on an active experience, but too many movies now are like baby food, where everything's ground up, simplified, so the viewer can consume it and forget it easily. In Everybody Knows, there are many shots of an entire family sitting at a table or at a party, with all the characters in focus, so the viewer can choose who and what subplot to focus on.You seem to advocate for a cinema open to the ambiguous nature of reality.

There's a great book that was written 50 years ago, Hitchcock/Truffaut, which is wonderful but had a side effect. At one point, Hitchcock claims that, at the beginning of every shoot, he has the entire movie already visualized in his head. In my opinion, that presupposes that the movie has no life of its own. When dealing with emotions, some movies, like Everybody Knows, find their form along the way thanks to the collaboration between the director, the actors, the DP, and the rest of the crew. That's the life of a film.