Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | December 2016 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

As reported here last weekend, Brian De Palma's Raising Cain and Carlito's Way were screened back-to-back Friday afternoon/evening at The Film Society of Lincoln Center, as part of its current series, "Going Steadi: 40 Years of Steadicam." The Lincoln Center series is the cover story of the current issue of Film Comment, which includes an interview with Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown, who mentions Carlito's Way as a prime example of the Steadicam being used to shoot in conjunction with cuts, or edits, to create a dynamic flow of images (as opposed to elaborate single-take sequences). The interview was conducted by John Bailey-- here is the excerpt:

As reported here last weekend, Brian De Palma's Raising Cain and Carlito's Way were screened back-to-back Friday afternoon/evening at The Film Society of Lincoln Center, as part of its current series, "Going Steadi: 40 Years of Steadicam." The Lincoln Center series is the cover story of the current issue of Film Comment, which includes an interview with Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown, who mentions Carlito's Way as a prime example of the Steadicam being used to shoot in conjunction with cuts, or edits, to create a dynamic flow of images (as opposed to elaborate single-take sequences). The interview was conducted by John Bailey-- here is the excerpt:What do you think of movies that use the Steadicam as a real-time technique-- the entire film being shot in a continuous take? I think of a movie like Russian Ark.

Of course I enjoyed Russian Ark, and likewise several more recent, less rigorous examples that invisibly devided the operating chore into more manageable hunks. But they are tours de force and inevitably degrade the stoytelling to achieve a continuousness that non-cineastes might not even notice. I love cuts. Moviegoers don't even notice them, and I loved shooting for cuts with Steadicam. At best, such as in the subway sequences of Carlito's Way, they acquire an energy and dynamism and pure bold kinetic energy that would be inevitably diminished by any attempt at a "one-er." I cherish the Western cinema tradition as is... cuts and all!

Earlier this month, No Film School's Emily Buder interviewed Brown, and asked him to name "some of those greatest Steadicam shots which you have not operated yourself"...

Well, I was immediately a fan of the Goodfellas shot. God, there are just tons of them. The one from Boogie Nights I loved. Carlito's Way has some fantastic shots in it. Kill Bill. There's astounding Steadicam in that. And a vast number of foreign films. An inability to think of them as a sign that there are so many that are spectacular. It's like asking somebody, "What are your favorite violin solos in history?" and they flood in on you, the most astonishing ones by this and that artist.The important thing that I learned—and we've all learned—is Steadicam is a rather crappy invention. By itself, it doesn't do a thing. In the hands of a gifted operator, it is an instrument and is of no more use than the skill of the operator. It just barely allows a gifted human being to do this amazing trick: to run along with their ever-moving corpus. Out the other end comes an astonishing dolly shot smooth as glass.

Not only that, it's a dolly shot that can do stuff a dolly can't. As a fingertip operation, you could put the lens precisely where it wants to be, not just in dolly to the right, but in French curves. It would drive a dolly group crazy. Instinctively putting the lens where you want as boom up and down, and traverse left and right and aim, pan, and tilt. Everywhere your feet can take you and your arms can put this thing, there is the potential path for a lens. But the point isn't to be flashy.

The point is to let these storytelling shots show you what you—the viewer—ideally would love to see; where you would put your eye if you were standing on that set looking. We do this a million times a day. Human beings are fabulous camera operators of our own eyes, and our own eyes are superbly stabilized. When you run, you don't see a jerky shot. You see a very smooth Steadicam shot. We instinctively lean left and right, stand up and move around, to see what we want to see. I think that is a devastating argument against handheld: human beings don't see in the shaky way that handheld presents the world. In fact, it's stupid that your audience would see a shakier vision than your actors would see.

There's a strong argument, I think, for at least being as stable as your own magnificent little internal Steadicam. Your inner ear tells your eye muscles how to move to eliminate the bumps. Look straight across the room and fix your eyes on something and shake your head up and down violently. It just sits there, right? Shake your head side to side. It just sits there. But if that was a camera, you couldn't watch it. Now, watch this: tilt your head to one side. The room does not tilt. Your brain is conditioned to perceive the room as level no matter what angle your eye is. Why? Because evolution didn't find that of any interest for keeping us alive. It's really fundamental stuff. I could be a great bore on this subject, but I'm not a fan of handheld, and that's why the Steadicam exists. I wouldn't have been able to put it in those terms 40 years ago, but it's become quite clear to me.

When you dart your eyes around left or right and fix on something and dart to the other side of the room and look, there are only maybe 30% or 50% of Steadicam operators that can do that with a Steadicam. There's almost nothing else that can do what is called a saccad. A saccad is when you dart your eyes from one side of the room to the other.

TIME's Stephanie Zacharek mentions Brian De Palma's Mission To Mars in her review of Passengers, which was released in theaters yesterday:

TIME's Stephanie Zacharek mentions Brian De Palma's Mission To Mars in her review of Passengers, which was released in theaters yesterday:Passengers’ director is Morten Tyldum (The Imitation Game), working from a script by Jon Spaihts, and he vests much of the movie with a buzzing neon glow. (The space-walk scenes, contrasting glo-stick luminescence with inky blackness, are particularly beautiful.) But the movie runs aground in the last third: It’s as if Tyldum and Spaihts know they can’t get too wiggy, so they take a hard right and try to land their ship in more conventional territory.Along the way they make what appears to be a failed attempt to channel the intense doomed romanticism of Brian De Palma’s Mission to Mars (specifically, the sorrowful and glorious scene in which astronaut Connie Nielsen fails to save her fellow astronaut husband, Tim Robbins). By that point, Tyldum has crashed his ship, figuratively speaking—inside this failed picture there’s a sicker, darker, more truthful one crying to get out. But for a while, Passengers is really going for something. The movie it might have been is lost in space, alone, never to be seen by mere mortals. All we can see from Earth are its few brightly burning scraps, but at least it’s something.

Zacharek on The Martian and Mission To Mars

"De Palma, himself a high school science fair winner, approached space as a mystery, a problem beautiful in its vast unsolvability. Scott, all about solutions, gives us the most seemingly authentic Mars money can buy. That doesn't make it the best."

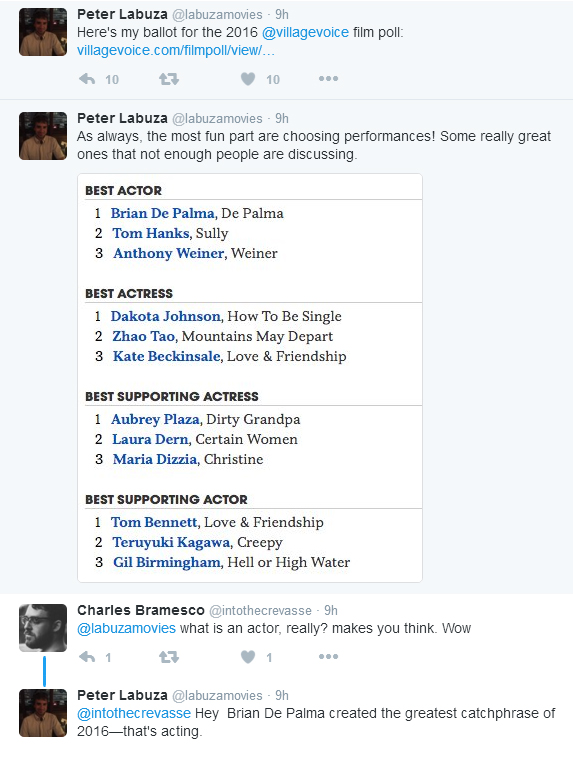

EACH INCLUDED DE PALMA IN TOP 3 BEST ACTOR CATEGORY FOR 2016 VILLAGE VOICE POLL As can be seen at left, Peter Labuza included a couple of documentary subjects, including Brian De Palma, in his top three actors list for the Village Voice Film Poll 2016. Simon Abrams placed De Palma as his third best actor. De Palma ranks as the seventh best documentary of 2016 in the poll.

As can be seen at left, Peter Labuza included a couple of documentary subjects, including Brian De Palma, in his top three actors list for the Village Voice Film Poll 2016. Simon Abrams placed De Palma as his third best actor. De Palma ranks as the seventh best documentary of 2016 in the poll.

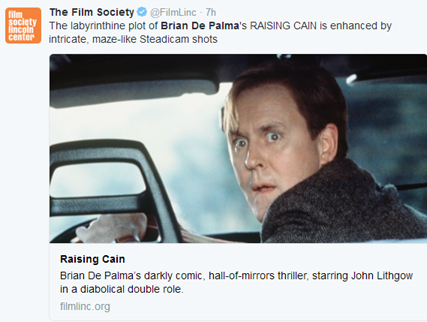

The Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York began a series on Friday (December 16th) titled "Going Steadi: 40 Years of Steadicam." Brian De Palma's Raising Cain screens tonight at 8:45 as part of the series, and again on Friday December 23rd, at 4:30pm. On Friday, you can make it a De Palma double feature by sticking around for the 6:30pm screening that day of Carlito's Way, also part of the series.

The Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York began a series on Friday (December 16th) titled "Going Steadi: 40 Years of Steadicam." Brian De Palma's Raising Cain screens tonight at 8:45 as part of the series, and again on Friday December 23rd, at 4:30pm. On Friday, you can make it a De Palma double feature by sticking around for the 6:30pm screening that day of Carlito's Way, also part of the series.Here is the program description of Raising Cain:

"Brian De Palma’s darkly comic, hall-of-mirrors thriller stars a deliciously deranged John Lithgow in a diabolical double role: as a mild-mannered child psychiatrist and his evil twin brother, who both take to kidnapping and murder in order to procure toddlers for a bizarre psychological study. Out-of-left-field plot twists, electrifying set pieces, and Hitchcockian doubles (and triples and quadruples) abound, while the film’s labyrinthine plot and disorienting, dreamlike tone are enhanced by the intricate, maze-like Steadicam shots."

I'll do a couple more brief posts centered around this fest in the next couple of days.

io9's Katharine Trendacosta posted an excerpt today from Carrie Fisher's new book, The Princess Diarist, in which she writes about her experience making Star Wars. The excerpt is about the dual auditions for Star Wars and Carrie, including a few exchanges between Fisher and Brian De Palma, as well as George Lucas, of course:

io9's Katharine Trendacosta posted an excerpt today from Carrie Fisher's new book, The Princess Diarist, in which she writes about her experience making Star Wars. The excerpt is about the dual auditions for Star Wars and Carrie, including a few exchanges between Fisher and Brian De Palma, as well as George Lucas, of course:George Lucas held his auditions for Star Wars in an office on a lot in Hollywood. It was in one of those faux-Spanish cream-colored buildings from the thirties with dark orange-tiled roofs and black-iron-grated windows, lined with sidewalks in turn lined with trees—pine trees, I think they were, the sort that shed their needles generously onto the street below—and interrupted by parched patches of once-green lawns.Everything was a little worse for the wear, but good things would happen in these buildings. Lives would be led, businesses would prosper, and men would attend meetings—hopeful meetings, meetings where big plans were made and ideas were proposed. But of all the meetings that had ever been held in that particular office, none of them could compare in world impact with the casting calls for the Star Wars movie.

A plaque could be placed on the outside of this building that states, “On this spot the Star Wars films conducted their casting sessions. In this building the actors and actresses entered and exited until only three remained. These three were the actors who ultimately played the lead parts of Han, Luke, and Leia.”

I’ve told the story of getting cast as Princess Leia many times before—in interviews, on horseback, and in cardiac units—so if you’ve previously heard this story before, I apologize for requiring some of your coveted store of patience. I know how closely most of us tend to hold on to whatever cache of patience we’ve managed to amass over a lifetime and I appreciate your squandering some of your cherished stash here.

George gave me the impression of being smaller than he was because he spoke so infrequently. I first encountered his all-but-silent presence at these auditions—the first of which he held with the director Brian De Palma. Brian was casting his horror film Carrie, and they both required an actress between the age of eighteen and twenty-two. I was the right age at the right time, so I read for both George and Brian.

George had directed two other feature films up till then, THX 1138, starring Robert Duvall, and American Graffiti, starring Ron Howard and Cindy Williams. The roles I met with the two directors for that first day were Princess Leia in Star Wars and Carrie in Carrie. I thought that last role would be a funny casting coup if I got it: Carrie as Carrie in Carrie. I doubt that that was why I never made it to the next level with Carrie—but it didn’t help as far as I was concerned that there would have to be a goofy film poster advertising a serious horror film.

I sat down before the two directors behind their respective desks. Mr. Lucas was all but mute. He nodded when I entered the room, and Mr. De Palma took over from there. He was a big man, and not merely because he spoke more— or spoke, period. Brian sat on the left and George on the right, both bearded. As if you had two choices in director sizes. Only I didn’t have the choice—they did. Brian cleared his bigger throat of bigger things and said, “So I see here you’ve been in the film Shampoo?”

I knew this, so I simply nodded, my face in a tight white-toothed smile. Maybe they would ask me something requiring more than a nod.

“Did you enjoy working with Warren?”

“Yes, I did!”

That was easy! I had enjoyed working with him, but Brian’s look told me that wasn’t enough of an answer.

“He was . . .”

What was he? They needed to know! “He helped me work . . . a lot. I mean, he and the other screenwriter . . . they worked with me.” Oh my God, this wasn’t going well. Mr. De Palma waited for more, and when more wasn’t forthcoming, he attempted to help me.

“How did they work with you?”

Oh, that’s what they wanted to know! “They had me do the scene over and over, and with food. There was eating in the scene. I had to offer Warren a baked apple and then I ask him if he’s making it with my mother—sleeping with her—you know.”

George almost smiled; Brian actually did. “Yes, I know what ‘making it’ means.”

I flushed. I considered stopping this interview then and there. But I soldiered on.

“No, no, that’s the dialogue. ‘Are you making it with my mother?’ I asked him that because I hate my mother. Not in real life, I hate my mother in the movie, partly because she is sleeping with Warren who’s the hairdresser. Lee Grant played my mom, but I didn’t really have any scenes with her, which is too bad because she’s a great actress. And Warren is a great actor and he also wrote the movie, with Robert Towne, which is why they both worked with me. With food. It sounded a lot more natural when you talk with food in your mouth. Not that you do that in your movies. Maybe in the scary movie, but I don’t know the food situation in space.” The meeting seemed to be going better.

“What have you done since Shampoo?” George asked.

I repressed the urge to say I had written three symphonies and learned how to perform dental surgery on monkeys, and instead told the truth.

“I went to school in England. Drama school. I went to the Central School of Speech and Drama.” I was breathless with information. “I mean I didn’t just go, I’m still going. I’m home on Christmas vacation.”

I stopped abruptly to breathe. Brian was nodding, his eyebrows headed off to his hair in something like surprise. He asked me politely about my experience at school, and I responded politely as George watched impassively. (I would come to discover that George’s expression wasn’t indifferent or anything like it. It was shy and discerning, among many other things, including intelligent, studious, and— and a word like “darling.” Only not that word, because it’s too young and androgynous, and besides which, and most important, George would hate it.)

“What do you plan on doing if you get one of these jobs you’re meeting on?” continued Brian.

“I mean, it really would depend on the part, but . . . I guess I’d leave. I mean I know I would. Because I mean—”

“I know what you mean,” Brian interrupted. The meeting continued but I was no longer fully present—utterly convinced that I’d screwed up by revealing myself to be so disloyal. Leave my school right in the middle for the first job that came along?

Soon after, we were done. I shook each man’s hand as I moved to the door, leading off to the gallows of obscurity. George’s hand was firm and cool. I returned to the outer office knowing full well that I would be going back to school.

“Miss Fisher,” a casting assistant said.

I froze, or would have, if we weren’t in sunny Los Angeles. “Here are your sides. Two doors down. You’ll read on video.” My heart pounded everywhere a pulse can get to.

The scene from Carrie involved the mother (who would be memorably played by Piper Laurie). A dark scene, where the people are not okay. But the scene in Star Wars—there were no mothers there! There was authority and confidence and command in the weird language that was used. Was I like this? Hopefully George would think so, and I could pretend I thought so, too. I could pretend I was a princess whose life went from chaos to crisis without looking down between chaoses to find, to her relief, that her dress wasn’t torn.

Surrounded by Cuban filmmakers and students, the American film director Brian De Palma spoke in Havana about the challenges of making films, his stories and the elements that, in his opinion, directly influence the psychology of characters and interpreters.Special guest of the 38th International Festival of New Latin American Cinema, the creator of such films as Scarface (1983), Casualties of War (1989), Dressed to Kill (1980), and The Untouchables (1987), among others, discussed during the two hours his conceptions as an artist, in an atmosphere of continuous exchanging of ideas.

"Young people have no excuses not to make art-- the digital era is conducive to less production costs, they only need a camera and a laptop to start creating," said the director of Redacted, a highly acclaimed film during the year 2007.

"Although it is good to tell our own stories, we must try to direct the materials of others, to get in touch with their way of creating, to think, to structure the characters," said this eternal admirer of the work of Alfred Hitchcock, well-known wizard of suspense.

On the violence in his films and the treatment of women, De Palma confessed smilingly that "the history of cinema is the history of men photographing women"; Which is why he does not hesitate to interfere with women in their films, even if they contain an exaggerated nuance of action.

He also commented to those present the need to pay attention to elements such as sound and music during the processes of conception of a work, since these intervene as an actor more within the plot and psychology of the film.

Finally, when asked about his expectations with the Havana Festival, he exclaimed: ¡Viva Cuba !, aware that for more than two decades the locals have been anxiously awaiting this visit.

Brian De Palma is passionate about the seventh art, focusing on the work of Alfred Hitchcock, Roman Polanski and Jean-Luc Godard.

The thriller was its standard for several years, although it is two works of fantastic genre The Phantom of the Paradise (1974) and above all, the enormous success of the first adaptation of a novel of Stephen King, Carrie (1976), that placed him as one of the most interesting authors of the new Hollywood cinema, which emerged in the 1970s.

The era of new technology and communications means opening young filmmakers to an unlimited universe of ideas to be developed, US director Brian De Palma said here Thursday.Before an audience of mostly filmmakers and students from different latitudes, De Palma meant the cost of production of any film, a reason enough for young people to develop the projects they want.

However, warned the director of films such as The Untouchables (1987) and Scarface (1983), [they] should endeavor to give meaning to the film resources employed in terms of a story that, in this context and repeated so much, become clichés.

De Palma explained that with the new possibilities of technology, shots are often used without apparent reason for the development of the plot, to the detriment of the seventh art.

From their experience, the young directors must worry about writing a good story or working with someone who knows how to do it, choose the actors with criteria, assemble it and present it to the different film festivals, where, surely, they will find financing for their completion and distribution.

More focusing on himself, Brian De Palma acknowledged that sometimes it is important to escape his own stories and tell others, while sharing some of his most relevant creative experiences in the production of films such as Casualties of War and Redacted.

Influenced by the world of cinematography, De Palma detailed in passages of his films that are a clear evocation to the genius of the suspense Alfred Hitchcock, or the great innovator, the Soviet follower Eisenstein.

On the latter, he remembered the scene of the stroller with the baby that descends alone on the stairs in the middle of a shooting, which he then readapted for The Untouchables: 'it's very good, why do it only once,' he joked.

Held back from previous editions, the renowned filmmaker was finally able to attend the Festival of New Latin American Cinema, with the purpose of imparting a master class and to visit the International School of Cinema and Television of San Antonio de los Baños, to whose anniversary of foundation is dedicated this 38 edition.

Nancy Allen then posted a comment on Irvin's post: "We sure had some fun making Home Movies. Kirk was wonderful! How fortunate we were to work with him."

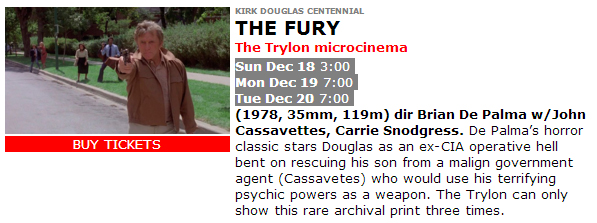

Meanwhile, this past Sunday, Live Mint's Uday Bhatia posted a tribute looking at five of Kirk Douglas' most memorable scenes, and included one from The Fury:

Last action heroAlong with George Miller’s The Man from Snowy River (1982), The Fury represents the best of late-period Douglas.

In this 1978 film by Brian De Palma, he plays Peter Sandza, an ex-CIA agent who survives an assassination attempt and resurfaces years later in search of his telekinetic son, who has been kidnapped by a shadowy intelligence organization.

Pursued by his son’s captors, he takes two bumbling beat cops (one of whom is played, hilariously, by Dennis Franz, the future NYPD Blue star) hostage and commandeers their vehicle. De Palma, master of the elaborate chase, wasn’t fond of cars, a possible reason why the sequence is played mostly for laughs.

De Palma gave impetus to several fledgling actors—John Travolta, Robert De Niro, Margot Kidder—in his early films, but this was the first time he worked with a huge star.

Douglas is very much the old-school pro in the film, and in this scene. He deadpans through most of it, which only serves to make the panic of his co-passengers more hilarious; his sideways glance when one of them says, belatedly, “Somebody’s after you, is that it?” is a minor classic. Few actors over 60 would have consented to ending a big action sequence with their pants around their ankles. That Douglas does this without looking ridiculous is testament to his willingness to subvert his own virile image, and belief in his own star quality.