George Lucas held his auditions for Star Wars in an office on a lot in Hollywood. It was in one of those faux-Spanish cream-colored buildings from the thirties with dark orange-tiled roofs and black-iron-grated windows, lined with sidewalks in turn lined with trees—pine trees, I think they were, the sort that shed their needles generously onto the street below—and interrupted by parched patches of once-green lawns. Everything was a little worse for the wear, but good things would happen in these buildings. Lives would be led, businesses would prosper, and men would attend meetings—hopeful meetings, meetings where big plans were made and ideas were proposed. But of all the meetings that had ever been held in that particular office, none of them could compare in world impact with the casting calls for the Star Wars movie.

A plaque could be placed on the outside of this building that states, “On this spot the Star Wars films conducted their casting sessions. In this building the actors and actresses entered and exited until only three remained. These three were the actors who ultimately played the lead parts of Han, Luke, and Leia.”

I’ve told the story of getting cast as Princess Leia many times before—in interviews, on horseback, and in cardiac units—so if you’ve previously heard this story before, I apologize for requiring some of your coveted store of patience. I know how closely most of us tend to hold on to whatever cache of patience we’ve managed to amass over a lifetime and I appreciate your squandering some of your cherished stash here.

George gave me the impression of being smaller than he was because he spoke so infrequently. I first encountered his all-but-silent presence at these auditions—the first of which he held with the director Brian De Palma. Brian was casting his horror film Carrie, and they both required an actress between the age of eighteen and twenty-two. I was the right age at the right time, so I read for both George and Brian.

George had directed two other feature films up till then, THX 1138, starring Robert Duvall, and American Graffiti, starring Ron Howard and Cindy Williams. The roles I met with the two directors for that first day were Princess Leia in Star Wars and Carrie in Carrie. I thought that last role would be a funny casting coup if I got it: Carrie as Carrie in Carrie. I doubt that that was why I never made it to the next level with Carrie—but it didn’t help as far as I was concerned that there would have to be a goofy film poster advertising a serious horror film.

I sat down before the two directors behind their respective desks. Mr. Lucas was all but mute. He nodded when I entered the room, and Mr. De Palma took over from there. He was a big man, and not merely because he spoke more— or spoke, period. Brian sat on the left and George on the right, both bearded. As if you had two choices in director sizes. Only I didn’t have the choice—they did. Brian cleared his bigger throat of bigger things and said, “So I see here you’ve been in the film Shampoo?”

I knew this, so I simply nodded, my face in a tight white-toothed smile. Maybe they would ask me something requiring more than a nod.

“Did you enjoy working with Warren?”

“Yes, I did!”

That was easy! I had enjoyed working with him, but Brian’s look told me that wasn’t enough of an answer.

“He was . . .”

What was he? They needed to know! “He helped me work . . . a lot. I mean, he and the other screenwriter . . . they worked with me.” Oh my God, this wasn’t going well. Mr. De Palma waited for more, and when more wasn’t forthcoming, he attempted to help me.

“How did they work with you?”

Oh, that’s what they wanted to know! “They had me do the scene over and over, and with food. There was eating in the scene. I had to offer Warren a baked apple and then I ask him if he’s making it with my mother—sleeping with her—you know.”

George almost smiled; Brian actually did. “Yes, I know what ‘making it’ means.”

I flushed. I considered stopping this interview then and there. But I soldiered on.

“No, no, that’s the dialogue. ‘Are you making it with my mother?’ I asked him that because I hate my mother. Not in real life, I hate my mother in the movie, partly because she is sleeping with Warren who’s the hairdresser. Lee Grant played my mom, but I didn’t really have any scenes with her, which is too bad because she’s a great actress. And Warren is a great actor and he also wrote the movie, with Robert Towne, which is why they both worked with me. With food. It sounded a lot more natural when you talk with food in your mouth. Not that you do that in your movies. Maybe in the scary movie, but I don’t know the food situation in space.” The meeting seemed to be going better.

“What have you done since Shampoo?” George asked.

I repressed the urge to say I had written three symphonies and learned how to perform dental surgery on monkeys, and instead told the truth.

“I went to school in England. Drama school. I went to the Central School of Speech and Drama.” I was breathless with information. “I mean I didn’t just go, I’m still going. I’m home on Christmas vacation.”

I stopped abruptly to breathe. Brian was nodding, his eyebrows headed off to his hair in something like surprise. He asked me politely about my experience at school, and I responded politely as George watched impassively. (I would come to discover that George’s expression wasn’t indifferent or anything like it. It was shy and discerning, among many other things, including intelligent, studious, and— and a word like “darling.” Only not that word, because it’s too young and androgynous, and besides which, and most important, George would hate it.)

“What do you plan on doing if you get one of these jobs you’re meeting on?” continued Brian.

“I mean, it really would depend on the part, but . . . I guess I’d leave. I mean I know I would. Because I mean—”

“I know what you mean,” Brian interrupted. The meeting continued but I was no longer fully present—utterly convinced that I’d screwed up by revealing myself to be so disloyal. Leave my school right in the middle for the first job that came along?

Soon after, we were done. I shook each man’s hand as I moved to the door, leading off to the gallows of obscurity. George’s hand was firm and cool. I returned to the outer office knowing full well that I would be going back to school.

“Miss Fisher,” a casting assistant said.

I froze, or would have, if we weren’t in sunny Los Angeles. “Here are your sides. Two doors down. You’ll read on video.” My heart pounded everywhere a pulse can get to.

The scene from Carrie involved the mother (who would be memorably played by Piper Laurie). A dark scene, where the people are not okay. But the scene in Star Wars—there were no mothers there! There was authority and confidence and command in the weird language that was used. Was I like this? Hopefully George would think so, and I could pretend I thought so, too. I could pretend I was a princess whose life went from chaos to crisis without looking down between chaoses to find, to her relief, that her dress wasn’t torn.

The Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York began a series on Friday (December 16th) titled "Going Steadi: 40 Years of Steadicam." Brian De Palma's Raising Cain screens tonight at 8:45 as part of the series, and again on Friday December 23rd, at 4:30pm. On Friday, you can make it a De Palma double feature by sticking around for the 6:30pm screening that day of Carlito's Way, also part of the series.

The Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York began a series on Friday (December 16th) titled "Going Steadi: 40 Years of Steadicam." Brian De Palma's Raising Cain screens tonight at 8:45 as part of the series, and again on Friday December 23rd, at 4:30pm. On Friday, you can make it a De Palma double feature by sticking around for the 6:30pm screening that day of Carlito's Way, also part of the series.

Paul Sylbert, the production designer on Blow Out and many other classic films, died November 19, at his home in Jenkintown, Pa., according to

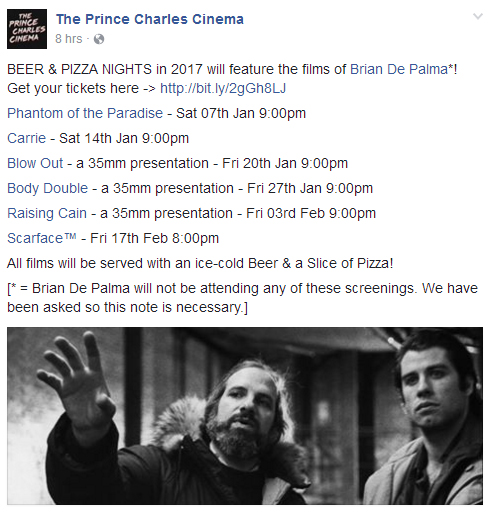

Paul Sylbert, the production designer on Blow Out and many other classic films, died November 19, at his home in Jenkintown, Pa., according to  Brian De Palma's Body Double will be paired with Krzysztof Kieślowski's A Short Film About Love this Friday (November 25) and Sunday (November 27) at

Brian De Palma's Body Double will be paired with Krzysztof Kieślowski's A Short Film About Love this Friday (November 25) and Sunday (November 27) at