Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | September 2016 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

In the same interview, De Palma mentions that around that time, he had also signed on to direct a remake of Billy Wilder's Ace In The Hole, "a film denouncing the power of the media," for which David Mamet had written the screenplay. Eventually he made The Bonfire Of The Vanities, which dealt with similar themes.

The Final Girls (Anna Bogutskaya and Olivia Howe) hosted a screening last night of Brian De Palma's Carrie at the ICA in London. The screening, which was part of Scalarama film month, was followed by a panel discussion made up of Michael Blyth (BFI Festivals Programmer), Catherine Bray (Film4 Editorial Director and Producer) and Dr. Alison Pierse (Lecturer at York University). The discussion is summarized by Smoke Screen's Owen Van Spall:

The Final Girls (Anna Bogutskaya and Olivia Howe) hosted a screening last night of Brian De Palma's Carrie at the ICA in London. The screening, which was part of Scalarama film month, was followed by a panel discussion made up of Michael Blyth (BFI Festivals Programmer), Catherine Bray (Film4 Editorial Director and Producer) and Dr. Alison Pierse (Lecturer at York University). The discussion is summarized by Smoke Screen's Owen Van Spall:Brian de Palma's films and his own statements have been controversial to say the least, something the Carrie panel tackled right from the start of their conversation. This is a film that begins with a tracking shot that has become somewhat notorious; the camera journeys through a steamy changing room as Carrie’s high school gym class are seen in various stages of nudity. This is far from the last time in the movie de Palma’s camera will linger on female flesh either: with female cheerleaders on the pitch and high school bad girl Chris’s bra-less torso getting plenty of screen time. This is also one of many de Palma films that put their female characters through the wringer, to put it politely.Thus the panel agreed that at some point they had all been driven to ask themselves: “Is it cool to like Carrie [and de Palma]?” But the consensus was that, after repeat viewings and after taking a few steps back to reconsider de Palma’s career as a whole, rejecting Carrie entirely as mysoginistic felt too much like throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Alison Pierce for example praised the way the film - largely through Sissy Spacek’s intense performance - effectively transmitted the desperate sadness of the plight of this hapless but incredibly powerful young woman. You empathise with Carrie as almost a Frankenstein-like figure, a victim created by monstrosity. The panel also noted how both De Palma and King explored her victimhood in interesting ways - with the narrative and characterisation of Carrie seeming at times to provoke the viewer to almost want this pathetic figure to get tormented. De Palma arguably manipulates viewers to effectively swing between delighting in seeing Carrie suffer, and yearning to see her inflict terrible vengeance on her tormentors turn. The bucket of blood sequence, with its long, almost gleeful build up in slow motion, was much discussed as an example of this. Viewers might want to ask themselves; do you maybe sneakily want that rope to be pulled, and the bucket to fall, knowing both what the immediate humiliating result will be, and what will happen next?

Author Stephen King and de Palma also have an interesting kingship, as Catherine Bray noted: they are good at “serious fun” - taking a ludicrous concept and imbuing it with genuine terror and emotional weight. Of course, Carrie can simply be enjoyed as campy, shlockly fun, with Michael Blyth half-joking if you could convert this film easily into a musical given its tone and setting. Regardless, the panel noted that the film remains very striking from a cinematographic perspective, with a visual approach that teeters on the deliciously overblown at times. De Palma throws in a tonne of tricks that he would become well known for, including diopter lens shots, and the use of montage which really works well in the prom terror sequence, as Carrie starts to come apart, her attention and powers jumping to various points as she singles out her enemies for destruction. The Smoke Screen in particular was struck by the deliriously bold lighting throughout the film too. Much of the film’s early sequences seem drenched in a warm, apple pie glow, but in the prom night sequence sees de Palma start us off with a dreamy kaleidoscopic mix of purples and yellows that highlight how carried away Carrie is by her one moment of bliss, only to drench the entire affair in an insanely deep red shade once the psychic assault starts.

Meanwhile, blogger Harry Faint posted a brief review after watching Carrie, seemingly for the first time:

Even though I knew the plot and knew the rampage that was about to ensue when the bucket finally dropped, I was still in shock. The build up of this film is masterful, with the final slow motion sequence becoming a sickly sweet fantasy. The narrative is relatively simple and the pace is snappy, which makes the final sequence all the more painful to watch as carnage unravels as quickly as Carrie’s happiness. I was pleasantly surprised with how much I enjoyed it. There is an interesting use of De Palma blurring two images into a shot and I came away feeling that every visual was vital to the story – the prom sequence is such a great accomplishment in filmmaking. It felt real, Carrie’s telekinesis is never questioned or explained as the supernatural. In fact, nothing is over explained, or if things are explained it is through use of visuals and absence of voice. However, one thing I disliked is the reuse of Herrman’s 4 notes from Psycho (Hitchcock, 1960), but it still works.Hearing the bucket swing back and forth and nothing else is as clever as it is haunting. You know you like a film when you wake up the next morning still thinking about it.

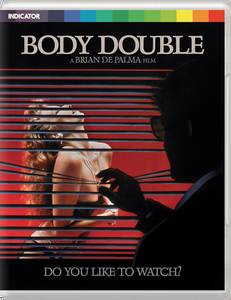

Indicator is a new British Blu-ray/DVD spinoff of Powerhouse Films that will focus on cult movies. Its first two releases, both on October 24, will be limited dual-format editions of Brian De Palma's Body Double and John Carpenter's Christine (the latter will include audio commentary by Carpenter and star Keith Gordon). Both are region 2 releases limited to 5000 copies each.

Indicator is a new British Blu-ray/DVD spinoff of Powerhouse Films that will focus on cult movies. Its first two releases, both on October 24, will be limited dual-format editions of Brian De Palma's Body Double and John Carpenter's Christine (the latter will include audio commentary by Carpenter and star Keith Gordon). Both are region 2 releases limited to 5000 copies each.ROBBIE COLLIN: WHY 'BODY DOUBLE' DESERVES ANOTHER LOOK - "IT ISN'T TRASH, IT'S UNREPENTANTLY TRASHY"

The Telegraph's Robbie Collin previews the Indicator release by saying, "When it was released in 1984, Brian De Palma's follow-up to Scarface was dismissed as exploitative trash. And that's exactly what he wanted." Here's a bit of an excerpt:

Few directors seize an opportunity like Brian De Palma. In 1983, riding high on the success of Scarface, De Palma was offered a three-film deal by Columbia Pictures, who wanted to see where this stylish and controversial pulp auteur would go next.The following year, he repaid them with a film that was so squalid, so bloodthirsty, and so critically pummelled that three weeks after its release – roughly, the amount of time it took to vanish from cinemas – the studio had torn up his contract, painted out his private parking space, and thrown him off the lot.

The film the then-44-year-old director gave them was Body Double: a Los Angeles-set erotic thriller in which a Peeping Tom becomes the key witness in the murder of a nymphomaniac trophy wife. Among its notable traits are an apparently wilfully bad lead performance from a virtual nobody, entire scenes openly plagiarised from Alfred Hitchcock, walk-on appearances from genuine adult film stars, and a sequence in which the aforementioned desperate housewife is skewered on an enormous safe-cracking drill. As far as Columbia was concerned, it was a $10 million fiasco. But for De Palma, the outrage was worth every last buck...

...Talking to Quentin Tarantino for a 1994 edition of the BBC’s arts series Omnibus, De Palma admitted that “after these battles…I said, ‘OK, you want to see violence? You want to see sex? Then I’ll show it to you.’” In short, the film was an almighty up yours – aimed not just at the censors, but also the critics, commentators and Hollywood players for whom Brian De Palma films were just brand-name misogynistic trash.

Except Body Double isn’t trash, misogynistic or otherwise. It’s unrepentantly trashy – not the kind of film you watch while your parents or kids are in the house, or with your curtains open. But it’s also a complex, provocative suspense thriller that bears comparison with the three immaculate Hitchcock classics – Vertigo, Psycho and Rear Window – it gleefully drags through the sludge.

Joe Napolitano passed away July 23 in Los Angeles, following a battle with cancer, Variety reports. He was 67. Napolitano was a respected TV director who spent the early part of his career as first assistant director on feature films, where he worked most prominently on every Brian De Palma picture between 1981 and 1987: Blow Out, Scarface, Body Double, Wise Guys, and The Untouchables. He also worked with De Palma on the Bruce Springsteen music video, Dancing In The Dark (1984). Napolitano discussed the making of Body Double for the Carlotta Ultra Collector's Box of the film, which was released in France last December.

Joe Napolitano passed away July 23 in Los Angeles, following a battle with cancer, Variety reports. He was 67. Napolitano was a respected TV director who spent the early part of his career as first assistant director on feature films, where he worked most prominently on every Brian De Palma picture between 1981 and 1987: Blow Out, Scarface, Body Double, Wise Guys, and The Untouchables. He also worked with De Palma on the Bruce Springsteen music video, Dancing In The Dark (1984). Napolitano discussed the making of Body Double for the Carlotta Ultra Collector's Box of the film, which was released in France last December.Following Wise Guys, which had co-starred Danny DeVito, Napolitano worked as first assistant director on DeVito's directorial feature debut, Throw Momma From The Train.

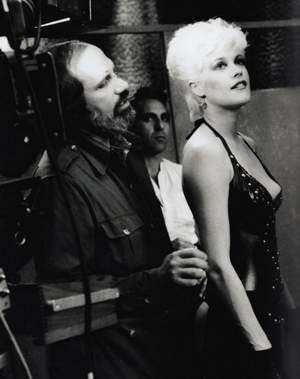

Napolitano can be seen shadowing De Palma on the sets of Body Double and The Untouchables in the two pics below:

Danny McBride, co-creator of HBO's Vice Principals, talked to Uproxx's Steven Hyden about the show, mentioning Brian De Palma in regards to the upcoming second season. Here's the excerpt from Hyden's article:

Danny McBride, co-creator of HBO's Vice Principals, talked to Uproxx's Steven Hyden about the show, mentioning Brian De Palma in regards to the upcoming second season. Here's the excerpt from Hyden's article:Even by the insane standards of the HBO comedy’s inaugural season, Sunday’s Vice Principals season finale was, well, very insane. Over the course of nine polarizing episodes, in which co-creators Jody Hill and Danny McBride walked the razor’s edge between pitch-black comedy and disquieting psychological drama, Vice Principals followed the efforts of school administrators Neal Gamby (Danny McBride) and Lee Russell (Walton Goggins) to overthrow their new boss, Belinda Brown (Kimberly Hebert). Along the way, there were some extremely uncomfortable moments, including an act of arson at Brown’s home and a horrifying night of destruction prompted by a bottle of gin.And then there was Sunday’s episode, in which [SPOILERS AHEAD] Gamby and Russell finally succeed in getting rid of Brown. Better yet, they’re appointed co-principals of the school. But just when everything appears to have worked out for the show’s protagonists/villains, Gamby is gunned down in the school’s parking lot by a mysterious masked figure, and apparently left for dead.

Vice Principals ended its first season as it began — uneven, erratic, and yet also thrillingly unpredictable and unique. It wasn’t perfect, but Vice Principals was a welcome oddity amid an increasingly conformist television landscape. As the conventions of “Good TV” are codified and reduced to formula — with an established set of clearly defined storytelling perspectives and moral objectives — Vice Principals stubbornly went against the grain, never letting the audience off the hook by telling it how to feel about its deeply flawed characters.

Initially conceived as an 18-episode limited-run series, Vice Principals already has its second and final season in the can. “Everyone could watch it now if HBO would just release it. It’s ready. It’s there for you to see,” McBride told us Monday in a phone interview.

As for what viewers should expect from Vice Principals moving forward, McBride says “we were channeling a lot of John Hughes and ’80s teen comedy in the first season, and I feel like in the second season we start channeling a lot of Brian De Palma.”

The Platform jury at the Toronto International Film Festival, made up of Brian De Palma, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, and Zhang Ziyi, chose Pablo Larraín's Jackie for its $25,000 prize. The film stars Natalie Portman as Jacqueline Kennedy. The festival concluded today with that award and others, including the People's Choice Award, the fest's top honor, which went to Damien Chazelle's La La Land.

The Platform jury at the Toronto International Film Festival, made up of Brian De Palma, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, and Zhang Ziyi, chose Pablo Larraín's Jackie for its $25,000 prize. The film stars Natalie Portman as Jacqueline Kennedy. The festival concluded today with that award and others, including the People's Choice Award, the fest's top honor, which went to Damien Chazelle's La La Land.At the film's TIFF premiere, Larraín told Vanity Fair's Julie Miller that when producer Darren Aronofsky suggested the project to him, Larraín responded that he would only direct the film if Portman portrayed the title character. "I didn’t see anybody else playing her,” he told Miller. "It was a combination of elegance, sophistication, intelligence, and fragility. Beauty and sadness can be something very powerful in our culture."

Here's a further excerpt from Miller's article:

At the time, Larraín did not really love the script for the project; did not feel a personal connection to Kennedy; had never made a film about a female character; and honestly did not like traditional biopics. But he was certain of one thing he would do if Portman agreed to star.“I told her, ‘Look, I have not talked to the writer—but if I were to do this movie, I would take out all of the scenes you are not in.’”

The result is a fragmented retelling of the four days following John F. Kennedy’s assassination, told through the feverish prism of post-traumatic stress disorder. Larraín takes the same artistic liberty with Neruda, which doesn’t tell a linear life story so much as it gives viewers an original, entertaining experience that encapsulates the subject’s persona. In Neruda, Larraín does so by using the poet’s love of crime novels to fashion the film into a detective story, starring Gael García Bernal, about an inspector trying to track down his exiled title subject.

“When you make a movie about a poet from the 40s, my biggest fear is to make a boring movie,” Larraín explains. “We create a fiction over a non-fiction. I don’t expect these to be used as educational tools. I remember I was an exchange student in the U.S. for half a year, and I would go to high school and they would show movies about the Civil War, movies about Abraham Lincoln. And all of those movies were terrible. . .We worked hard not to make [these films] entertaining just to be entertaining, but there are a lot of interesting, fun elements there, and they are beautiful and very simple but sophisticated. They are character studies about a very specific time in these people’s lives, and being fascinated by the characters. What I've learned with cinema is you really have to be fascinated by the characters.”

Before making Jackie, though, Larraín—who did not grow up in the U.S.—had to find his personal connection to Kennedy.

As he told Aronofsky, who urged him to make the project, “I don't know why you are calling a Chilean to make a movie about Jackie Kennedy—but that’s your call.” And after his initial meeting with Portman, the filmmaker realized that his personal connection to Kennedy was still missing.

“I went home and I was like, there’s something else in here. I started Googling and on YouTube I found this White House tour from 1961 that I had no idea existed,” explains the director. “I couldn’t believe my eyes. I couldn’t believe what I was watching. . .She actually raised private money, and what she did was a restoration, going with a team of people all over the U.S. to find furniture that at some point was in the White House but was sold for different reasons. I thought it was just so beautiful the way she did it, and I fell in love with her watching that program—just the way she moved, the fragility, the way she explained things, how educated she was. This idealism that she had. It sounds naive, this Camelot thing to me, but once I got into it I found it very interesting and beautiful and deep even though I’m not American.”

Scarface remake would have been Larraín's "dream project"