Passion was treated as minor De Palma, and fair enough for a thriller built from an array of elements—doppelgangers, split-screen murders, music by Pino Donaggio, voyeuristic sexuality—that De Palma had used, more memorably, decades earlier. Still, it has something that so many mainstream American movies today are lacking: an appreciation for cinema’s irrational power over its audience. And De Palma, old-school enough that he closes Passion with a title card reading “The End,” made a film that’s best understood through the psychodramatic lens of classic noir, while at the same time working a twist on his own formula.

In discussing Passion as a dream narrative, one must be careful, because that’s a game that can keep the audience guessing. The heroine goes to bed at the beginning of the film, and subsequently is shown falling asleep and suddenly waking up nearly half a dozen times. De Palma adapted his script from a French thriller called Love Crime (Alain Corneau, 2010), from which Passion gets its Euro-chic setting, the framework of its murder plot, and a battle of feminine cunning that should appeal to anyone who feels the word “bitch” may be used admiringly. But Love Crime plays the material relatively straight, with a very different ending. The feverish dream angle belongs to De Palma’s version alone. So the best place to start is the one sequence I can say with confidence is “real,” the opening scene. Isabelle (Rapace) and Christine (McAdams), two coworkers at an ad agency, are meeting at Christine’s apartment after hours to discuss the latest campaign. As they share a drink and a few laughs, it’s instantly clear which of the two is dominant. Christine has perfect confidence, perfect style, perfect taste, a perfect apartment. Isabelle is much more timid and repressed. Buttoned-up in an asexual black pantsuit (which she’ll wear for most of the film, despite Christine’s many colorful costume changes), Isabelle is clearly in the thrall of her mentor, and thrilled that such an alpha-female would keep her as a confidante. She admires Christine—is it just professional, or something else? Then Christine’s perfect boyfriend arrives, and Isabelle, sensing that she’s become a third wheel, excuses herself and goes home. We see Isabelle drifting off to sleep, and then the story begins in proper: a tale of intrigue and murder as convoluted as any of Alfred Hitchcock‘s—and much clammier than Richard Wanley’s.

As a thriller, Passion has too many implausible twists to name. But as a glimpse into Isabelle’s psyche, it’s a hypnotic clash of identities. Isabelle competes with Christine. She sleeps with Christine’s boyfriend. Christine suddenly kisses Isabelle—a moment they scarcely dwell on—then teaches her to undo her top buttons to hook a male client. (“You’re more like me than you think,” Christine teases her.) And throughout this, the film’s style tilts towards insanity. Rapace plays Isabelle as a perpetually stunned figure, acting for most of the film like a helpless spectator, even to her own actions. The script is often daftly illogical; in one scene, Christine goes from threatening Isabelle to inviting her to a dinner party within a few seconds. Midway through, the film suddenly shifts into full-blown noir expressionism, with wall-to-wall canted angles and Venetian-blind shadows. The plot mechanisms by which someone may or may not get away with murder are as complex as they are irrelevant. Passion is more a series of anxious fantasies: to be Christine, to fuck Christine, to kill Christine. Though of course, in a nightmare, can you count on someone to stay dead?

The crowning moment, where Passion adds something valuable to De Palma’s canon, is the final set piece. This scene is De Palma in overheated form, the sort of ludicrous sequence that gets excruciating suspense from being so drawn out, and it involves a murder taking place in Isabelle’s apartment late at night, just as a police inspector drops by to “pay his respects.” There are numerous things that are logically “off” with this scene, not the least of which is why the inspector, who by this point in the contorted plot has been thoroughly fooled, would choose to pay a social visit in the middle of the night. But the sequence builds to a fever pitch, and then climaxes with the money shot: Isabelle convulsing awake, in the same bed she’d drifted off to sleep in after that opening scene—only now with a crucial, impossible detail.

De Palma is self-aware filmmaker, not above referencing himself as well as his predecessors. The final shot of Passion, a high-angle view of the heroine waking up from a nightmare, is nearly identical to the shots that closed Carrie and Dressed to Kill. But here, De Palma adds one of his most mischievous touches: When Isabelle wakes up, the murder victim is still there, lying on the floor next to the bed, perfectly preserved from the prior sequence. As a finale, it’s a bonkers paradox: the construction of the editing means that this final sequence (if not the entire plot of the film) simultaneously must be a dream and can’t be a dream. There is no logical explanation, nor can there be, nor should there be.

This kind of gamesmanship may turn some audiences off, as if the chain has been yanked a little too hard. But for such a modest, apparently trashy film, it’s also a sophisticated touch, and it relies on an audience willing to be subservient to the pure sounds and images that envelope them. It goes back to Richard Wanley’s epilogue, regaining his bearing after his feature-length nightmare; or to the hero of Caligari, confronting his horror back in real life; or to anyone who’s seen a scary movie late at night and finds it difficult to shake the unease. What De Palma’s Passion toys with, in a modern, old-fashioned way, is an idea both dreamlike and quintessentially cinematic: the fear (or hope) that what you’ve seen will be waiting for you on the other side.

Danny McBride, co-creator of HBO's Vice Principals, talked to Uproxx's Steven Hyden about the show, mentioning Brian De Palma in regards to the upcoming second season. Here's the excerpt from Hyden's article:

Danny McBride, co-creator of HBO's Vice Principals, talked to Uproxx's Steven Hyden about the show, mentioning Brian De Palma in regards to the upcoming second season. Here's the excerpt from Hyden's article:

The

The  Nashville's nonprofit film center,

Nashville's nonprofit film center,  Armond White reviews Oliver Stone's Snowden for

Armond White reviews Oliver Stone's Snowden for  Kim Jee-woon's thriller The Age of Shadows played out of competition at the Venice Film Festival, and at least two reviews have mentioned Brian De Palma's The Untouchables as inspiration for a train station shootout. And after Femme Fatale, one can't help but wonder if a thriller sequence using Ravel's Bolero isn't also inspired by De Palma. Here are a couple of links, with quotes:

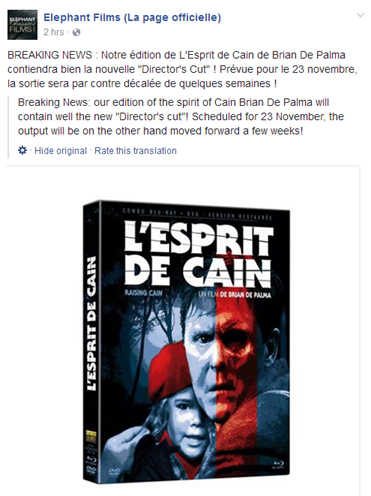

Kim Jee-woon's thriller The Age of Shadows played out of competition at the Venice Film Festival, and at least two reviews have mentioned Brian De Palma's The Untouchables as inspiration for a train station shootout. And after Femme Fatale, one can't help but wonder if a thriller sequence using Ravel's Bolero isn't also inspired by De Palma. Here are a couple of links, with quotes: Just a note that today, three big items are officially released. What is widely being hailed as one of the biggest Blu-ray releases to come along in a long while,

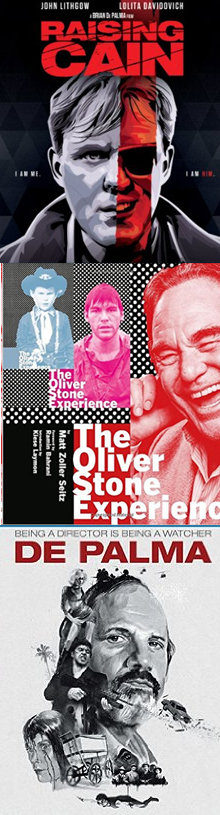

Just a note that today, three big items are officially released. What is widely being hailed as one of the biggest Blu-ray releases to come along in a long while,

Duncan Gray has posted an essay at

Duncan Gray has posted an essay at