"ALMOST MADE IT INTO THE UNTOUCHABLES"

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | April 2016 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

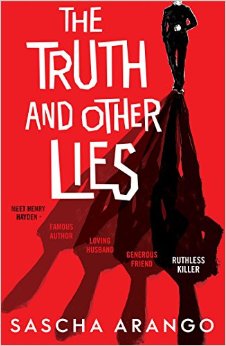

Deadline's Mike Fleming Jr. reports today that Brian De Palma is attached to direct the film adaptation of last year's novel The Truth And Other Lies. The novel, which won the European prize for best literary debut (the Prix Européen du Polar du Point, according to Fleming), was written by Sascha Arango, who had previously made a name for himself in Germany as a writer for television. Arango has adapted the novel into the screenplay for the film.

Deadline's Mike Fleming Jr. reports today that Brian De Palma is attached to direct the film adaptation of last year's novel The Truth And Other Lies. The novel, which won the European prize for best literary debut (the Prix Européen du Polar du Point, according to Fleming), was written by Sascha Arango, who had previously made a name for himself in Germany as a writer for television. Arango has adapted the novel into the screenplay for the film."I have tried to portray Henry Hayden as a human product of modern meritocracy, where the individual is no longer defined by moral integrity, but by power and success,” Arango said, according to Fleming. “In the Facebook era, the original becomes indistinguishable from fake. Success replaces faith and becomes religion.”

According to Fleming, the novel was optioned by Chockstone Pictures and Nick Wechsler Productions. Steve Schwartz, Paula Mae Schwartz and Nick Wechsler are the producers, with Roger Schwartz listed as a co-producer.

NOVEL REVIEW: VERY LITTLE EMOTION, MATTER-OF-FACT STYLE DESPITE HORROR, SEVERE STORMS...

In his review of the novel last year, Huffington Post's Jackie K. Cooper stated that the book's events were played out "with very little emotion. Arango’s style of writing is to make everything matter of fact no matter how horrific it becomes. It is a plodding way to write but somehow this technique becomes intensely interesting. It shouldn’t be but it is.

"The writing of this story is so bare bones that the locale is never clearly defined. You learn it takes place somewhere in Europe and it is a coastal village, but not much else. There are storms that occur here and some are very severe. There are people in the village with emotional problems and some of them are severe, but details as to why and how they arise are never specified."

A week and a half ago, at the Beaune Thriller Film Fest, De Palma told press that he was currently working to finalize the screenplay for Lights Out, which he hopes to begin shooting this summer in China and Canada.

Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver was released 40 years ago, and will get a special screening Thursday, April 21, at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. Ahead of that, last week The Hollywood Reporter posted an "oral history" of the film. In the following excerpt from the beginning of the article, screenwriter Paul Schrader, producer Michael Phillips, and Scorsese discuss how they became involved, noting the important role Brian De Palma played in suggesting the right person to direct the picture:

Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver was released 40 years ago, and will get a special screening Thursday, April 21, at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. Ahead of that, last week The Hollywood Reporter posted an "oral history" of the film. In the following excerpt from the beginning of the article, screenwriter Paul Schrader, producer Michael Phillips, and Scorsese discuss how they became involved, noting the important role Brian De Palma played in suggesting the right person to direct the picture:PAUL SCHRADER (screenwriter) I had a series of things falling apart, a breakdown of my marriage, a dispute with the AFI, I lost my reviewing job. I didn't have any money and I took to drifting, more or less living in my car, drinking a lot, fantasizing. The Pussycat Theater in L.A. would be open all night long, and I'd go there to sleep. Between the drinking and the morbid thinking and the pornography, I went to the emergency room with a bleeding ulcer. I was about 27, and when I was in the hospital, I realized I hadn't spoken to anyone in almost a month. So that's when the metaphor of the taxi cab occurred to me — this metal coffin that moves through the city with this kid trapped in it who seems to be in the middle of society but is in fact all alone. I knew if I didn't write about this character I was going to start to become him — if I hadn't already. So after I got out of the hospital, I crashed at an ex-girlfriend's place, and I just wrote continuously. The first draft was maybe 60 pages, and I started the next draft immediately, and it took less than two weeks. I sent it to a couple of friends in L.A., but basically there was no one to show it to [until a few years later]. I was interviewing Brian De Palma, and we sort of hit it off, and I said, "You know, I wrote a script," and he said, "OK, I'll read it."MICHAEL PHILLIPS (producer) [My then-wife] Julia and I were living on Nichols Beach, and our next-door neighbors were Margot Kidder and Jennifer Salt, and Brian De Palma was living with Margot at the time. Brian said to me one day, "There's this guy who has written a screenplay. It's not really for me, but I think it's your taste." It was incredibly pure, a very honest piece of work. So I went to my two partners at the time, Julia and Tony Bill, and proposed we acquire it for $1,000, and by a two-to-one vote — Tony and I voted to acquire it, and Julia voted against it — we acquired the option.

MARTIN SCORSESE (director) Brian gave me the script. I reacted very viscerally, almost mystically to it and its tone and the struggle of the character. But I was still trying to get them to take me seriously as a filmmaker. I'd done a low-budget independent film called Who's That Knocking [at My Door] and an exploitation film for Roger Corman called Boxcar Bertha. I liked Julia a lot, but she kept pushing me away, dismissive, but funny. She'd just tell me, "Come around again when you've done something more than Boxcar Bertha."

PHILLIPS It took several years to get made. One day Paul suggested we see a rough cut of [Scorsese's] Mean Streets, and midway through, I really felt this is our guy. Johnny Boy [played by Robert De Niro] is our actor. So we made a proposal to Marty and Bob's agent. They both had to do it or neither. I mean it was silly, in retrospect.

ROBERT DE NIRO (Travis Bickle) We all liked the script a lot and wanted to do it and were committed to it.

MICHAEL CHAPMAN (cinematographer) I realized years later that it's a kind of folk tale or urban legend. It's a werewolf movie in a weird way. Even his hair changes. There are these things that are wandering around in the night that are dangerous. In this case, the werewolf saves the girl, instead of killing the girl.

PHILLIPS We went about trying to shop it, and it was rejected. Then Marty went off to do Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore and Bobby went off to do Godfather [Part II] and 1900.

SCORSESE I remember Robert De Niro winning that Oscar for Godfather: Part II. That night Francis Coppola accepted for Bob, who was shooting another film, and I was there, and Francis told me, "It's going to be good for your film."

Jim Ridley, the Nashville Scene writer and editor, died April 8. "He had collapsed after suffering a cardiac event in the Scene offices on March 28, and never regained consciousness," stated Nashville Scene's Jack Silverman in a post. "He was 50 years old." Ridley was one of the sharpest film critics around, and his review of Brian De Palma's Passion, from 2013, cuts deep into the movie with insightful wit to spare. Here's an excerpt:

Jim Ridley, the Nashville Scene writer and editor, died April 8. "He had collapsed after suffering a cardiac event in the Scene offices on March 28, and never regained consciousness," stated Nashville Scene's Jack Silverman in a post. "He was 50 years old." Ridley was one of the sharpest film critics around, and his review of Brian De Palma's Passion, from 2013, cuts deep into the movie with insightful wit to spare. Here's an excerpt:Passion is a Brian De Palma movie for a world chilled by narcissism and held rapt by its own reflection. The director has devoted his career to the warping impact of surveillance culture, where everyone is a watcher or passive voyeur — in front of the big screen, the TV, the computer monitor — and conversely, everyone is watched. Long before the laptop, the iPhone and Skype, there was De Palma Nation, a place where everybody was either on camera or behind one. Because of the bulky, prohibitively expensive equipment, the latter group was limited — either to professionals, like John Travolta's sound engineer in Blow Out, or obsessives, like Keith Gordon's gadget-prone amateur sleuth in Dressed to Kill.But technology has surpassed the spycam society forecast in early De Palma classics like Hi, Mom! and Sisters. Anyone with a cellphone can be both star and director of his own YouTube-documented life, which sounds like nothing so much as the setup for one of De Palma's loopy, sinuous erotic thrillers. In fact, it's a pretty apt description of Passion, a wickedly funny exercise in the audience misdirection and technocratic hoodwinkery that's been this filmmaker's stock in trade for nearly five decades. Its corporate milieu is an orchard of gleaming little trademark Apples, most of them concealing worms.

De Palma borrows the hothouse plot of Alain Corneau's 2010 French thriller Love Crime — its co-writer, Natalie Carter, gets a dialogue credit here — but gives it a cold-to-the-touch sheen and a clammy metallic palette that's at ironic odds with the title. (It was shot on 35mm but transferred to digital, which mutes the steamy lushness that marks De Palma's thrillers.) When color bleeds through this sterile environment, it's typically the siren-red lipstick worn by Christine (Rachel McAdams), a coolly kinky executive at a Berlin advertising agency where the glass planes and slashing angles suggest the Apple Store of Dr. Caligari.

So self-obsessed she likes her lovers to wear a doll-mask facsimile of her own features, Christine is grooming an avid protégé, Isabelle (Noomi Rapace), who covets her boss's power and modernist digs down to the upholstery on her sofa. De Palma poses them in the frame like mirror images, and Christine can't help but try shaping her underling into a human selfie. "You need some color," she coos to Isabelle, applying her lipstick as well as her lips.

But Isabelle isn't such an eager apprentice once Christine hogs the credit for her viral smartphone ad campaign — a spot that only looks like an updating of the reality-TV "Peeping Toms" gag that opens De Palma's 1973 Sisters, but is in fact a replica of an actual guerrilla YouTube ad. The ad mixes the director's favorite ingredients, sex and spying — and so does the mad soap-opera-on-steroids revenge fantasy that follows, as Isabelle sleeps with Christine's shady colleague-lover (Paul Anderson) and her boss rigs a nasty public payback.

Each step of this battle is registered on screens, even screens within screens, creating a hall of mirrors that fires the gaze back at the gazer: the "ass cam" that secretly films leering gawkers, the sex tape where the parties stare into each other's eyes only when they watch themselves on a monitor. Imagine what this plethora of recording devices means to the man who once called film 24 lies a second. De Palma plays this mediated alienation for queasy-funny effect, as when Isabelle lies in bed with her hands in masturbatory position — only they're poised over her laptop rather than her lap. The two women's fight is personal, all right, but so much of it is waged on a digital playing field that they might as well be videogame avatars. But some things you still have to do the old-fashioned way. That's when a knife comes in handy.

Shot by Almodovar's longtime cinematographer Jose Luis Alcaine — the Spanish director's resolutely De Palma-esque melodrama The Skin I Live In was good practice — Passion shows De Palma reveling in the blatant craziness of his contrivances. (This features perhaps the quintessential De Palma line of dialogue: "You have a twin sister?") Rapace's Edvard Munch cheekbones and startled eyes do the heavy lifting of her performance, but McAdams, firmly back in Mean Girls mode, delivers her vicious lines with venomous zest. De Palma introduces more and more variables into the scenario, leading to a split-screen showstopper where high art and low crime compete for the viewer's attention. Guess what wins.

De Palma, the documentary about Brian De Palma made by Jake Paltrow and Noah Baumbach, screened this past Friday (April 8) at the 35th Istanbul Film Festival. The film will screen again tomorrow, April 11. The fest's description of the film goes like this: "An exciting look at the idiosyncratic cinema of the living legend, Brian De Palma. The director, who differs from his peers with his extraordinary career, sits with Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow and candidly discusses his 29 features, shorts, and fell through projects. Scenes from his inimitable films accompany the conversation that ranges from the secrets of his mind-blowing mise-en-scène, to anecdotes from his sets, and film theory. De Palma is a riveting documentary that will not only embrace cinéphiles and the director´s fans, but also audiences who are unfamiliar with his work."

De Palma, the documentary about Brian De Palma made by Jake Paltrow and Noah Baumbach, screened this past Friday (April 8) at the 35th Istanbul Film Festival. The film will screen again tomorrow, April 11. The fest's description of the film goes like this: "An exciting look at the idiosyncratic cinema of the living legend, Brian De Palma. The director, who differs from his peers with his extraordinary career, sits with Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow and candidly discusses his 29 features, shorts, and fell through projects. Scenes from his inimitable films accompany the conversation that ranges from the secrets of his mind-blowing mise-en-scène, to anecdotes from his sets, and film theory. De Palma is a riveting documentary that will not only embrace cinéphiles and the director´s fans, but also audiences who are unfamiliar with his work."

What is your impression of the evolution of the thriller genre?

De Palma: That’s really hard to say, because mysteries are done a lot on television, all types of forms. They explore every story and character form you can imagine. But since I’m more of a visual storyteller, I find inspiration in the ‘40s and ‘50s where you told your stories more visually, rather than relying on the dialogue to explore the mystery.

Can you share your recollections of filming Passion?

De Palma: Well, you know, it’s made from a French film—I know both of the actresses that were in the French film—in fact, I talked to Ludivine yesterday. Unfortunately, when the film was made, the director was very ill, and so there was a lot of difficulty getting through the material. And I sort of felt from the actresses that they were not given the kind of range to explore their characters. In retelling the story in English, I had two actresses that knew each other very well, that took the story and their involvement into all kinds of bizarre directions, that made it a lot more intriguing. And I added a certain surrealistic element to it that I think improved the original.

Any opinions on current trends in new films?

De Palma: Of course there will be new fantastic movies. One disturbing problem is, of course, a lot of the new generation is watching movies on telephones and iPads and computers, so they’re not used to seeing things on a large screen. Which I think is a great loss, because some of the great classics are composed for the large screen. I mean, I don’t see how you could explain Once Upon A Time In The West or some of David Lean’s great movies unless you show this largeness, the scope that he portrayed on the screen. So that’s going to be kind of lost, but with every new technical invention, like I’m looking at right now, there are great advantages, and you discover new forms in order to tell stories.

Which filmmakers inspire you?

De Palma: Well, I live in New York and I spend a lot of time with a group of young directors that live downtown. And I quite like their work. One is Wes Anderson, and the other is Noah Baumbach. And they make movies entirely different than I do, but I find their work quite original. And I’ve known these directors for years. We try to meet once a week, and talk about cinema, and what’s going on, and what we like and what we don’t like.

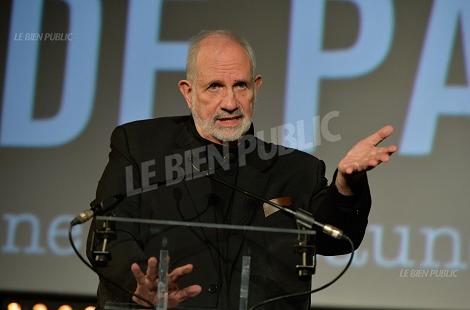

The picture at left, from France 3 TV, shows Brian De Palma on stage during Saturday's Cinema Masterclass at the Beaune International Thriller Film Festival. I'll post more about that this week, but for now, here is what De Palma told Alain Grasset at Le Parisien regarding his current project, Lights Out: "Yet another thriller-but I love so much this genre - which tells the story of a blind Chinese girl whose father is involved in a secret operation with the CIA. It will take place between China and Canada. I would like my film to be a kind of mixture between Mission: Impossible and Wait Until Dark, with Audrey Hepburn. Hopefully, I will start shooting this summer." Metro News mentioned the other day that the screenplay for Lights Out is still being worked on and finalized.

The picture at left, from France 3 TV, shows Brian De Palma on stage during Saturday's Cinema Masterclass at the Beaune International Thriller Film Festival. I'll post more about that this week, but for now, here is what De Palma told Alain Grasset at Le Parisien regarding his current project, Lights Out: "Yet another thriller-but I love so much this genre - which tells the story of a blind Chinese girl whose father is involved in a secret operation with the CIA. It will take place between China and Canada. I would like my film to be a kind of mixture between Mission: Impossible and Wait Until Dark, with Audrey Hepburn. Hopefully, I will start shooting this summer." Metro News mentioned the other day that the screenplay for Lights Out is still being worked on and finalized.

Some nice photos (taken by Philippe Bruchot) from the Beaune International Thriller Film Festival have been posted at Le Bien Public today, which paid tribute to Brian De Palma. De Palma received a standing ovation. So far, two French outlets have posted interviews with De Palma today from Beaune: Metro News and 20 Minutes. The interviews cover such topics as reality TV, Donald Trump, trying to work for television and having to fight for final cut, and De Palma's current project, Lights Out, for which he is currently finalizing the script with an eye to begin shooting this summer. I'll get translations of those interviews later this weekend. For now, here are a couple more photos:

Some nice photos (taken by Philippe Bruchot) from the Beaune International Thriller Film Festival have been posted at Le Bien Public today, which paid tribute to Brian De Palma. De Palma received a standing ovation. So far, two French outlets have posted interviews with De Palma today from Beaune: Metro News and 20 Minutes. The interviews cover such topics as reality TV, Donald Trump, trying to work for television and having to fight for final cut, and De Palma's current project, Lights Out, for which he is currently finalizing the script with an eye to begin shooting this summer. I'll get translations of those interviews later this weekend. For now, here are a couple more photos:

Brian De Palma's Carrie will have midnight screenings this Friday and Saturday, April 1 and 2, at the IFC Center in New York City. The screenings, which will be from DCP, kick off a thirteen-film midnight series, "Stephen King on Film." The IFC description of the series reads, in part, "Presented in honor of the 40th anniversary of Carrie (1976, Brian De Palma), the horror classic adapted from King’s first novel and the first of what would be countless films and TV productions derived from King’s work, the series showcases more than three decades of terrifying cinema inspired by the writer—an extensive, but by no means exhaustive selection."

Brian De Palma's Carrie will have midnight screenings this Friday and Saturday, April 1 and 2, at the IFC Center in New York City. The screenings, which will be from DCP, kick off a thirteen-film midnight series, "Stephen King on Film." The IFC description of the series reads, in part, "Presented in honor of the 40th anniversary of Carrie (1976, Brian De Palma), the horror classic adapted from King’s first novel and the first of what would be countless films and TV productions derived from King’s work, the series showcases more than three decades of terrifying cinema inspired by the writer—an extensive, but by no means exhaustive selection."