3RD VOLUME OF 'FAITH & SPIRITUALITY IN MASTERS OF WORLD CINEMA', PUBLISHED NEXT MONTH

Amazon link

Religious Imagery In The Films Of Brian De Palma

(blog post by Ryan M. Holt from February 28, 2014)

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | January 2015 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Religious Imagery In The Films Of Brian De Palma

(blog post by Ryan M. Holt from February 28, 2014)

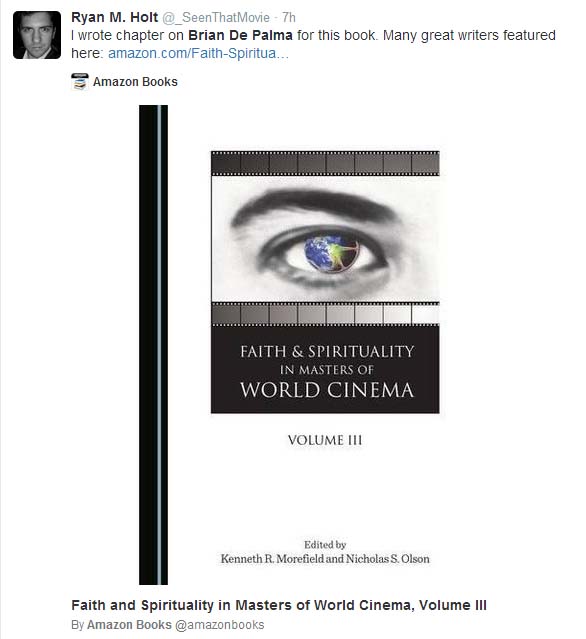

Eurogamer's Graeme Virtue posted an article today about Ocean Software's video game adaptation of Brian De Palma's The Untouchables, which he recalls came out a couple of years after the film. "Things only get confusing in the late 1980s and early 1990s," states Virtue, "when Ocean Software were licensing major Hollywood action films willy-nilly, then enthusiastically marketing their game tie-ins to consumers who were often too young to go and see the actual movie. In these cases, the experiences of game and movie sometimes become so entwined that it's impossible to separate the different memories." Here's an excerpt in which he provides details of the Untouchables game:

Eurogamer's Graeme Virtue posted an article today about Ocean Software's video game adaptation of Brian De Palma's The Untouchables, which he recalls came out a couple of years after the film. "Things only get confusing in the late 1980s and early 1990s," states Virtue, "when Ocean Software were licensing major Hollywood action films willy-nilly, then enthusiastically marketing their game tie-ins to consumers who were often too young to go and see the actual movie. In these cases, the experiences of game and movie sometimes become so entwined that it's impossible to separate the different memories." Here's an excerpt in which he provides details of the Untouchables game:The Untouchables, which arrived on 8-bit and 16-bit almost two years after Brian De Palma's 1987 movie had been a sizeable critical and commercial hit, felt marvellous at the time: an expansive, polished Prohibition-era shoot-em-up that offered up six relatively distinct mini-games. Thankfully, none of them involved completing a sliding block puzzle of Sean Connery's scowling face as Irish beat cop Malone, although many included the illicit thrill of a bootleg liquor gauge, even if your dogged G-Man was mostly destroying the booze rather than imbibing it. My experience on the Spectrum should have been the most lo-fi of all the home computer versions, but it somehow seemed like the classiest - enviably crisp sprites rendered in a consistent palette of black and cool blue, accompanied by a series of digitised mugshots that kinda, sorta looked like at least some of the actors.Intentionally or not, The Untouchables was also a system-seller, as the downside of having six completely different levels was having to load almost every single one of them separately. Ownership or access to a disk-drive-enabled Spectrum +3 was absolutely essential for maximum enjoyment. On old-fashioned cassette, the tussle for Chicago supremacy between Eliot Ness and Al Capone became a downtime-punctuated crawl. To exacerbate matters, the first level was actually the worst - a platform scramble round an anonymous warehouse, with you as Kevin Costner's dourly single-minded Ness, tasked with gathering evidence against the notorious crime boss through the time-honoured process of wasting gangsters, hopping between precariously-stacked pallets and picking up violin cases to access a Thompson sub-machine gun.

Even Ocean must have suspected that floaty platforming didn't showcase their game at its best, as they widely released the second level as a demo instead. This turned out to be a masterstroke, because that instalment - based on a bootlegger shoot-out on a bridge at the Canadian border - is the best of the lot. In the spirit of the arcade game Cabal, it's a thrilling shooting gallery where your character is also visible on-screen, rolling across the ground while firing off rifle rounds and destroying hooch barrels. A separate binocular scope nominally shows where you're aiming, but it's pretty easy to gauge from the trail of dustclod ricochets and trenchcoat-wrapped bodies you leave in your trigger-happy wake.

The third level, where you heft a shotgun in a tense alleyway shootout and swap between your four Untouchables to keep the mission-vital ones alive, is almost as good. But it's level four - where the action switches from side-on to top-down - that is especially memorable, as it recreates the most iconic scene in the movie, a haphazard shootout at a railway station that takes place while a baby's pram bumps through the crossfire. It was De Palma's celebrated, agonisingly drawn-out tribute to the Odessa Steps massacre in the silent movie classic Battleship Potemkin.

Just as BDP atomised and expanded what must have been a pretty sparse page of script - there's no dialogue, apart from a mimed scream of "my baby!" from the panicking mother - so the game extends it even further, charging you with managing the health of both Ness and the baby. Admittedly, it's another shooting gallery, albeit one that gives you the morally questionable option to use the pram as a temporary shield, safe in the knowledge that you can subsequently hustle it toward a restorative first-aid kit at the next landing. But 25 years on, another thought occurs: did The Untouchables accidentally invent the dreaded escort mission?

In the movie, the sharp suits for gangsters and G-Men alike were designed by Giorgio Armani. The score was just as lavish and lovingly tailored: a sumptuous, thrilling, Oscar-nominated suite by Ennio Morricone, It's unclear whether Ocean ever had the option to try and recreate the work of the Italian master, although 8-bit sound chips would certainly have struggled to recreate the querulous mouth organ and slightly detuned piano that characterise his soundtrack.

Instead, they opted for a very different but ultimately inspired route. Jonathan Dunn, Ocean's astonishingly talented in-house maestro, adapted the chirpy rags of Scott Joplin, imbuing the game with a bouncy, cheery energy that - while slightly at odds with the demands of mowing down dozens of wise guys - gives it an undeniable vim and vigour. It may have triggered a little cognitive dissonance in historians and cinephiles - ragtime was on its way out by the time Prohibition kicked in, and the syncopated style was also indelibly associated with The Sting, another sharply-tailored period piece - but it undeniably helped synthesise a cohesive identity for a potshot-pourri of a game. Deployed alongside the uniform colour scheme, it helped bind the disparate levels together, and make The Untouchables one of the most aesthetically successful video game movie adaptations of all time.

On January 23rd, the Oscars will host a double feature with the title "Street Clothes: Contemporary Costuming in New Hollywood." The two movies that will make up the double feature are Bob Fosse's All That Jazz (at 7:30 pm, from DCP) and Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise (at 9:50 pm, in 35mm). The screenings will take place at the Bing Theater at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The Oscars web page description of Phantom includes a sentence about the costumes:

On January 23rd, the Oscars will host a double feature with the title "Street Clothes: Contemporary Costuming in New Hollywood." The two movies that will make up the double feature are Bob Fosse's All That Jazz (at 7:30 pm, from DCP) and Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise (at 9:50 pm, in 35mm). The screenings will take place at the Bing Theater at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The Oscars web page description of Phantom includes a sentence about the costumes:

The other day, I posted a belated entry about a Brian De Palma retrospective at Cine Lume in Brazil. That retrospective ended yesterday, but it turns out there has been a separate De Palma series going on at Sala Walter da Silveira. This one started January 2nd, and runs through January 14th-- that last day, there will be a screening of a surprise De Palma film. This series includes many of De Palma films, and sometimes pairs them up with a film that inspired De Palma: Rear Window and Body Double were screened back-to-back on January 5th; Battleship Potemkin and The Untouchables were back-to-back last night; and Fritz Lang's The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse and De Palma's Snake Eyes were back-to-back earlier tonight. Monday, January 12th, Dario Argento's Suspiria will follow a screening of the movie that introduced Jessica Harper, De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise. Back on January 4th, both versions (Hawks' and De Palma's) of Scarface were screened back-to-back, and on Tuesday January 13th, De Palma's Scarface will screen again, this time following a screening of Jean Vigo's Zero For Conduct. I've never seen the latter, so if anyone knows how it may link to Scarface, please feel free to share. Which reminds me, all of these screenings are free.

The other day, I posted a belated entry about a Brian De Palma retrospective at Cine Lume in Brazil. That retrospective ended yesterday, but it turns out there has been a separate De Palma series going on at Sala Walter da Silveira. This one started January 2nd, and runs through January 14th-- that last day, there will be a screening of a surprise De Palma film. This series includes many of De Palma films, and sometimes pairs them up with a film that inspired De Palma: Rear Window and Body Double were screened back-to-back on January 5th; Battleship Potemkin and The Untouchables were back-to-back last night; and Fritz Lang's The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse and De Palma's Snake Eyes were back-to-back earlier tonight. Monday, January 12th, Dario Argento's Suspiria will follow a screening of the movie that introduced Jessica Harper, De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise. Back on January 4th, both versions (Hawks' and De Palma's) of Scarface were screened back-to-back, and on Tuesday January 13th, De Palma's Scarface will screen again, this time following a screening of Jean Vigo's Zero For Conduct. I've never seen the latter, so if anyone knows how it may link to Scarface, please feel free to share. Which reminds me, all of these screenings are free.

It is a testament to De Palma’s technique that Mission: Impossible’s most memorable sequence involves Tom Cruise hanging from a wire, and is not dependant on more traditional set pieces. The midnarrative set piece would become a tradition in the sequels, with De Palma’s successors putting their own spin on an IMF mission. The most important aspect of Hitchcock’s style that De Palma has made his own is his use of an omniscient point-of-view. De Palma’s camera may appear to approximate the subjective view of the characters, but his directorial control dictates what the viewer can see.An early example of this is the early sequence where Ethan Hunt witnesses his boss’s death by an unseen assailant via a camera in his glasses. All that Hunt (and by extension, the viewer) can see is a hand firing a gun directly at the camera. Later, when this scene is revealed to be staged, De Palma shows the action from a long shot to reveal what is really going on.

De Palma’s focus on suspense allows for other homages to Hitchcock, which are more decorative. Following his showdown with the villains, Ethan Hunt watches helplessly as a helicopter’s rotor blade spins toward him. This bit of action is reminiscent of a key moment from the climax of Strangers On A Train, where a technician sneaks under an out-of-control ferris wheel to switch off the mechanism, while the ride spins at high speed only a few inches above his head.

The introduction of the villain in the third act resembles the extended shot which identifies the twitching eyes of the killer in Hitchcock’s Young And Innocent. Starting from a long shot of a train, the camera pulls into a close-up of the killer’s hands through a window. This sequence also shows the influence of the Italian giallo, in De Palma’s use of mise-en-scene to conceal the villain’s identity. De Palma frames the character through a train compartment window, with his identity concealed by a half-closed blind. By framing the shot in this way, De Palma emphasises the character’s black gloves (a motif familiar from both the giallo genre and De Palma’s own Dressed To Kill) as he assembles a gun from the parts of a boombox.

De Palma is famous for his use of split screen to convey and build tension, and he integrates this technique into the opening action with a rather ingenious and subtle variation of the trope. As Jim Phelps (Jon Voight) directs his team, he watches their progress via cameras on their glasses. The respective point of views of these characters appear as a series of windows on his computer screen. In this way, De Palma renders his use of split screen as part of the mise-en-scene.

Sequences like this exemplify the degree to which De Palma is able to blend his style with the conventions of the genre he is working in.

With JJ Abrams making his feature film directorial debut on the third film in the series, George notes "a shift in the franchise away from visual stylists to filmmakers with a background in screen writing." George appreciates that the third film brings a deeper emphasis on characterization than the second film had done. "Dramatically, Mission: Impossible III is far more substantial and enjoyable experience than its predecessor," states George. "However, there is no disguising a certain cynicism to the focus on character development. Some of these arcs work, but help make Mission: Impossible 3 feel like the season of a TV show collapsed into two-and-a-bit hours." For George, the most recent film in the franchise, Ghost Protocol, is a more comedic, physical, and ironic entry that positively reflects director Brad Bird's background in animated film. He also likes that Bird's film solidifies the team aspect of the franchise. "By the end of Ghost Protocol," writes George, "Brad Bird has delivered the first instalment since Brian De Palma’s original that manages to include all of the elements of the original concept while playing to the strengths of the filmmaker orchestrating the action."

AN IMPASSIONED DEFENSE OF JOHN WOO'S 'MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE 2'

Meanwhile, Entertainment Weekly columnist Darren Franich responded to a reader who asked, "In what universe is John Woo’s flaming mess of a Mission: Impossible 2 better than JJ Abrams’ totally and completely acceptable Mission: Impossible 3?"

Franich responded, "This is an important thing that we need to talk about. Because I have heard some variation of this argument constantly for going on nine years now. The conventional wisdom, in a nutshell: Mission 2 is an incoherent action film with a ludicrous plot and bad acting; Mission 3 is a solid Bourne-era shaky-cam spy movie with a good plot and a great villain. Some people even go so far as to say that Mission: Impossible 3 is their favorite of the franchise.

"Let’s throw out that chestnut right here. Ghost Protocol is the best Mission: Impossible movie. It’s arguably the least Tom Cruise-y of the bunch: By the fourth movie, Ethan Hunt is a semi-emotionless action-bot. But as directed by Brad Bird, Ghost Protocol is a film made out of one great setpiece after another. Bird has an animator’s gift for beautiful geometry: Cruise fighting his way down a corridor in the prison sequence, Cruise fighting his way through every level of a parking garage in the climax. But Ghost Protocol is also the only film in the franchise where the whole Mission squad matters; Cruise’s low-key performance leaves plenty of room for Simon Pegg as the comedy relief, Paula Patton as the badass, and Jeremy Renner as the Cruise-in-training.

"Nobody loves or hates the first Mission: Impossible, and nobody really talks about it anymore. Which is too bad. The first film deserves more credit for starting off with such a fakeout. You think you’re watching a movie about a squad of jocular superspies on a mission that requires cool makeup and subterfuge. And then by the half-hour mark, the whole squad’s dead. (They didn’t just kill Kristin Scott Thomas; they killed Emilio Estevez.) Director Brian De Palma always loved the first-act Psycho twist—see Sisters, see Dressed To Kill—and so the first Mission: Impossible has one of the great left-turns in any vanilla-blockbuster. As a bonus, Mission: Impossible turns one of the franchise’s most iconic characters into a bad guy—the kind of bold storytelling choice that franchises used to make before everyone got too scared of fanboy freakouts.

"Thus, Mission: Impossible 2. This is the movie where Tom Cruise has beautiful flowing long hair and climbs a mountain with his bare hands (just like Shatner in Final Frontier.) This is the movie where Tom Cruise falls in love with Thandie Newton, but then sends her undercover to spy on her ex-boyfriend, charisma vacuum Dougray Scott. This is the movie where the bad guy’s plot focuses on stock options, and the movie where Cruise defeats the bad guy by driving a motorcycle really fast.

"Or something: The plot doesn’t really matter, because the plot never really matters in Mission: Impossible movies, because honestly 'plot' is maybe the eighth most important part of a movie. (Things it’s behind, in no order: Characters, Casting, Dialogue, Cinematography, Music, Lighting, THEMES.)

"The Mission movies give good directors big budgets and let them explore their peculiar fascinations in the context of a boring spy thriller, and Mission is the last great gasp of John Woo in the John Woo Era: The period of time when the Hong Kong director was everyone’s favorite cult-action obsession. All of Woo’s movies are bonkers if you read the plot summaries, but Woo’s style is still sui generis even after everyone ripped off The Matrix ripping off John Woo. Woo is dude who loves dudes with guns, but he’s also a hopeless romantic who loves soft-focus shots of lovers in love, and he has a ludicrously precise aesthetic but he was making movies pre-digital so his precision isn’t antiseptic (like the Wachowskis.)

"So Mission 2 is ludicrous, and wonderfully so. Cruise and Newton flirt via car chase, and nothing isn’t in slow motion. There’s a central weirdness to the Cruise-Newton-Scott triangle: Scott is sort of an Evil Cruise, and sometimes he even puts on Cruise’s face, and there’s a weird sense that Scott and Cruise are both just using Newton as neutral territory where they can fight. (As played by Richard Roxburgh, Hugh is one of the great vaguely-homoerotic henchmen in action-movie history.) There are a couple of Meth Woo scenes, like when Cruise emerges from an explosion flanked by a dove because Catholicism. The final action sequence is a motorcycle chase that turns into a martial arts fight, except it’s 'martial arts' being fought by two identical-looking white dudes. Mission 2 was written by Robert Towne, and Towne basically just took Notorious and deleted half the dialogue." [A La Mod note: Woo has cited To Catch A Thief as his biggest inspiration for MI2.] "It’s not good but it’s completely unfiltered, and it’s a prime expression of Cruisedom at its peak: When Cruise dies eighty years from now, every obituary will mention Cruise climbing the Mission 2 mountain by the end of the second paragraph.

"Everything about Mission 3 makes more sense, and nothing about Mission 3 is remotely as fun. After a high-tension flashforward opening, the movie flashes back to an interminable first act. Cruise is getting married! To a boring nurse played boringly by Michelle Monaghan! Cruise has a boring squad—pre-Nikita Maggie Q looking great and pre-Tudors Jonathan Rhys Meyers looking angry—and they set off on a mission to rescue the only cool character in the movie, a pre-Americans Keri Russell. Russell dies immediately, but not before Abrams films a helicopter chase through a bunch of windmills that is one of the most incoherent action scenes not filmed by Michael Bay.

"This was Abrams’ first movie, and he hadn’t quite developed his style for the big screen. So there are a lot of visual choices in Mission 3 that feel TV-like in the worst way—close-ups and shaky cameras, the weird bluescale mid-00s monochrome that made every big-budget action movie looks like the Michael Douglas scenes from Traffic. The movie often suggests an episode of 24 with more explosions and zero moral ambiguity. The exception is the Vatican City scene, an excellent setpiece that also features the genuinely strange vision of Tom Cruise’s face being molded into Philip Seymour Hoffman’s face."

Franich concludes with his ranking of the films:

1. Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol

2. Mission: Impossible

3. Mission: Impossible 2

4. Joe Carnahan’s unfilmed Mission: Impossible 3, which would’ve co-starred Kenneth Branagh, post-Matrix Carrie-Anne Moss, pre-Match Point Scarlett Johansson, and would’ve apparently been the “punk-rock” version of Mission: Impossible. 5. JJ Abrams’ filmed Mission: Impossible 3, a.k.a. pop-punk version of Mission: Impossible.

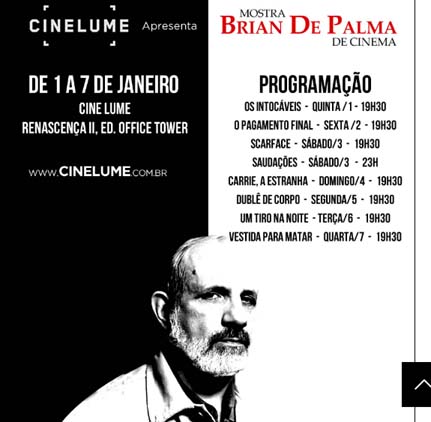

I'm a little late with this, but Cine Lume in São Luís, Maranhão, in Brazil, has been running a Brian De Palma retrospective since the first of January (2015). It winds down with a screening of Blow Out tonight (Tuesday), and Dressed To Kill tomorrow night (Wednesday). The other films in the retrospective are: The Untouchables, Carlito's Way, Scarface, Greetings, Carrie, and Body Double.

I'm a little late with this, but Cine Lume in São Luís, Maranhão, in Brazil, has been running a Brian De Palma retrospective since the first of January (2015). It winds down with a screening of Blow Out tonight (Tuesday), and Dressed To Kill tomorrow night (Wednesday). The other films in the retrospective are: The Untouchables, Carlito's Way, Scarface, Greetings, Carrie, and Body Double.

Thanks to Peter for sending in this link to a David Bordwell essay about Brian De Palma's Mission: Impossible, which was posted almost two weeks ago. Bordwell begins by stating, "The phrase 'visual storytelling' is a very modern invention." And yet, Bordwell points out, "Visual storytelling is seldom purely visual. In film, it needs concepts and music and noises and even dialogue to work most fully. We can learn a lot, I think, by starting with 'purely visual' passages and see how they’re reinforced by other inputs."

Thanks to Peter for sending in this link to a David Bordwell essay about Brian De Palma's Mission: Impossible, which was posted almost two weeks ago. Bordwell begins by stating, "The phrase 'visual storytelling' is a very modern invention." And yet, Bordwell points out, "Visual storytelling is seldom purely visual. In film, it needs concepts and music and noises and even dialogue to work most fully. We can learn a lot, I think, by starting with 'purely visual' passages and see how they’re reinforced by other inputs."Screenwriter David Koepp provided Bordwell with information about the production, and is quoted in the essay: "[De Palma] had another great idea, which was a reaction to the current state of summer movies at the time. He was tired of all the noise, of the bigger bigger bigger noisier noisier noisier setpieces, and desperately wanted to come up with one that used silence instead. He cackled at the idea of a big summer movie set piece that was predicated on silence."

"The result," Bordwell points out, "is nice case study in visual storytelling. It also indicates how even a pure instance needs non-visual elements to be understood."

Perhaps even more interesting is the next section of the essay, in which Bordwell analyzes the opening sequence of Mission: Impossible, focusing on the visual and audio information happening behind Emilio Estevez as Jack:

"Once the official Kasimov has given the name Ethan needs, the team’s goal is achieved and Jack can search it on his computer. In the meantime, Kasimov needs to be dragged off without fuss, and so must be given a drugged drink. That, we now understand, is the task of the woman hovering in the background of Jack’s shots. We’ve also been primed by the tray with bottle and glasses in the first shot.

"One option would be to pan or cut to the woman behind Jack and show her doping the drink. (This is what the shooting script seems to call for.) We might even see the woman’s face as she does it, but even if we don’t, a shot emphasizing her would give us a lot of other inessential information about the room.

"De Palma makes another choice. This woman is important only in terms of what she does. Panning to her, or supplying a separate shot, and showing her face might make her seem as important a character as Jack, Ethan, or Claire. She’s not. So De Palma reduces her to her function: doping the drink. And for economy, she does it in the same setup previously devoted to Jack’s reaction. She’s kept in the background."

As always, Bordwell illustrates his essay generously with many stills from the film.