Updated: Monday, December 22, 2014 7:00 PM CST

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | December 2014 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Thanks to Peter for sending in this link to a David Bordwell essay about Brian De Palma's Mission: Impossible, which was posted almost two weeks ago. Bordwell begins by stating, "The phrase 'visual storytelling' is a very modern invention." And yet, Bordwell points out, "Visual storytelling is seldom purely visual. In film, it needs concepts and music and noises and even dialogue to work most fully. We can learn a lot, I think, by starting with 'purely visual' passages and see how they’re reinforced by other inputs."

Thanks to Peter for sending in this link to a David Bordwell essay about Brian De Palma's Mission: Impossible, which was posted almost two weeks ago. Bordwell begins by stating, "The phrase 'visual storytelling' is a very modern invention." And yet, Bordwell points out, "Visual storytelling is seldom purely visual. In film, it needs concepts and music and noises and even dialogue to work most fully. We can learn a lot, I think, by starting with 'purely visual' passages and see how they’re reinforced by other inputs."Screenwriter David Koepp provided Bordwell with information about the production, and is quoted in the essay: "[De Palma] had another great idea, which was a reaction to the current state of summer movies at the time. He was tired of all the noise, of the bigger bigger bigger noisier noisier noisier setpieces, and desperately wanted to come up with one that used silence instead. He cackled at the idea of a big summer movie set piece that was predicated on silence."

"The result," Bordwell points out, "is nice case study in visual storytelling. It also indicates how even a pure instance needs non-visual elements to be understood."

Perhaps even more interesting is the next section of the essay, in which Bordwell analyzes the opening sequence of Mission: Impossible, focusing on the visual and audio information happening behind Emilio Estevez as Jack:

"Once the official Kasimov has given the name Ethan needs, the team’s goal is achieved and Jack can search it on his computer. In the meantime, Kasimov needs to be dragged off without fuss, and so must be given a drugged drink. That, we now understand, is the task of the woman hovering in the background of Jack’s shots. We’ve also been primed by the tray with bottle and glasses in the first shot.

"One option would be to pan or cut to the woman behind Jack and show her doping the drink. (This is what the shooting script seems to call for.) We might even see the woman’s face as she does it, but even if we don’t, a shot emphasizing her would give us a lot of other inessential information about the room.

"De Palma makes another choice. This woman is important only in terms of what she does. Panning to her, or supplying a separate shot, and showing her face might make her seem as important a character as Jack, Ethan, or Claire. She’s not. So De Palma reduces her to her function: doping the drink. And for economy, she does it in the same setup previously devoted to Jack’s reaction. She’s kept in the background."

As always, Bordwell illustrates his essay generously with many stills from the film.

"Scarface Redux" will be unveiled this Sunday (December 21st) at 8pm in Miami Beach, according to the Miami Herald's Debra K. Leibowitz. The screening will be one of the final events of this year's Borscht Film Festival, which began December 17th, and ends on the 21st. The Herald article states that Scarface Redux will play from 8-10pm, but it doesn't explain why that is about 45-minutes shorter than De Palma's film (perhaps they did not receive submissions for each of the 15-second clips). Leibowitz reports in the Herald: "A contest was held for the best scene submitted. Top prize included hotel and airfare for two to Miami, plus VIP tickets to all screenings and parties. Turns out the winner was local: Miami-based filmmaker Martell Harding, a 25-year old Florida International University graduate for his redux of Scene 94: The Shoot Up. Contest judges included Miami Herald film critic Rene Rodriguez, Rakontur Film’s Billy Corben and NBC-6 anchor Adam Kuperstein. Scarface Redux party fee is a $10 donation; free to those who submitted a clip."

Also screening at the fest this year is The Voice Thief, a new short film from Adan Jodorowsky, son of Alejandro Jodorowsky, starring Asia Argento. Borscht executive-produced the short, according to Miami New Times' Hans Morgenstern.

Page Six's Ian Mohr noted that Brian De Palma was among the guests at a screening of Jean-Marc Vallée's Wild last Thursday (December 4th). The screening was hosted by Ben Stiller and Noah Baumbach at NeueHouse in New York. Laura Dern, who appears in the film, was also in attendance, as was Meg Ryan and Chris Cornell.

Meanwhile, a couple of readers have sent along some very cool links that I have to share, even though I can't transcribe much right now. Rado sends along a link to a recent Vilmos Zsigmond Masterclass, a Higher Learning event which took place on August 8, 2014 at TIFF Bell Lightbox. Around the 35-minute mark, an audience member asks Zsigmond to talk about working with De Palma. Zsigmond talks about how De Palma had presented sketches for their first film together, Obsession. However, by the time they worked on The Black Dahlia three decades later, Zsigmond asked, "Brian, where are the sketches?" But De Palma waved him off, saying he didn't need them anymore. Zsigmond goes on to describe the complicated shots in The Black Dahlia and Bonfire Of The Vanities.

Drew sends along a link to the latest I Was There Too podcast, in which host Matt Gourley talks on the phone with Melody Rae, who played the woman with the baby carriage in the famous staircase scene in De Palma's The Untouchables. I can't listen to this one yet, but the podcast description says, "Melody tells us about completely improvising her memorable scene, how she handled the explosions, baby, & squibs, and working with Kevin Costner."

One more link: Cinema Space Tribute, a video montage put together by Max Shishkin that includes, among many others, imagery from De Palma's Mission To Mars.

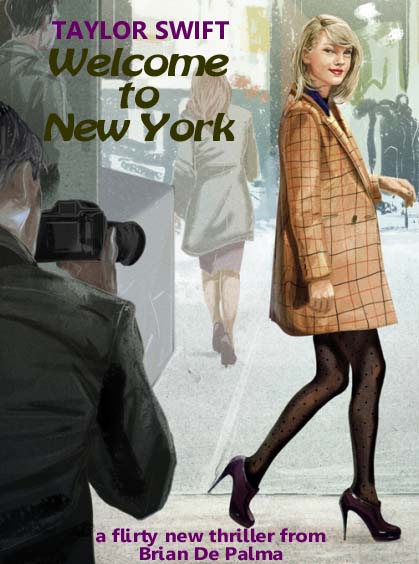

"Taylor was always aware of what she was doing. She invited us to look at her so that she would not be watched. A Rolling Stone cover story interview revealed her obsession with surveillance and paranoia that her private world could be invaded through technology. It was a year when a number of female celebrities had their privacy invaded in a very violent way, and Swift was well aware she was a target. Her paranoid outlook in the Rolling Stone profile — that she might be snapped changing in a dressing room or bathroom by some untrustworthy soul — was justifiable. We all increasingly live in a surveillance state. But Swift lives in a Brian De Palma movie.

"Taylor was always aware of what she was doing. She invited us to look at her so that she would not be watched. A Rolling Stone cover story interview revealed her obsession with surveillance and paranoia that her private world could be invaded through technology. It was a year when a number of female celebrities had their privacy invaded in a very violent way, and Swift was well aware she was a target. Her paranoid outlook in the Rolling Stone profile — that she might be snapped changing in a dressing room or bathroom by some untrustworthy soul — was justifiable. We all increasingly live in a surveillance state. But Swift lives in a Brian De Palma movie. --from an essay by Molly Lambert, posted at Grantland

[The "poster" presented here is an altered version of the illustration by Jonathan Bartlett that accompanies Lambert's essay at Grantland.]

RELATED:

Director Mark Romanek has been influenced by Stanley Kubrick, Brian De Palma, and now, Taylor Swift.

The Unloved - Phantom of the Paradise from RogerEbert.com on Vimeo.

Above is the twelfth edition of Scout Tafoya's video series, The Unloved (found at RogerEbert.com), which examines Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise. The series takes films that were received indifferently upon initial release and reveals the artistry that seemed to be overlooked in the critical and public dismissals of their time.

"Cult movies usually have to do something wrong in order to miss out on a first-run audience," Tafoya states in the video. "Idiosyncrasies and eccentricities pile up, and only a handful of people can see them as integral to the film's success as a crowd-pleasing oddity. In the case of Phantom Of The Paradise, the indifference that greeted it from critic and public alike seems much more baffling than its continued success in Winnipeg.

"It's easy to why Rocky Horror failed with mainstream audiences at first. It's entirely too pleased with itself, and features nothing in the way of sex or violence that audiences couldn't find in movies without self-conscious glam-rock all over the soundtrack. Phantom Of The Paradise had something to say, not to mention something to prove. Though it's rarely lumped in with many of its landmarks, the Phantom came out of the New Hollywood movement. By 1974, American artists were finally digging in and starting to take advantage of the creative autonomy offered by more adventurous studios. 1974 was a watershed year in particular, because it was when passion projects started flowing out of major studios. Directors were taking immense formal risks left and right, telling dark stories in daring ways, bowing to no one but their muse. There were huge successes, films that changed everything. And then there were films like Phantom Of The Paradise.

"Up until this point, Brian De Palma had been making bizarre little movies that mixed Godard and Hitchcock with abandon. Phantom Of The Paradise was his biggest film to date, and it remains his best. Perhaps sensing that he was the right man to make a crazed irreverent hash of classic literature, he grabbed his own pet influences to make a film that did for rock and roll what fellow enfant terrible Ken Russell had been doing for classical music."

In that same interview, Yablans told Jackson that he and De Palma would next be "doing a little film called Home Movies, with college students in New York." He said that after that, the two would be working on The Demolished Man. De Palma would indeed make Home Movies as his next film, but Yablans did not end up producing it. And unfortunately, the pair were never able to mount The Demolished Man, as The Fury, which is well-loved now, was not the hit they'd been hoping it would be.

Prior to taking it to 20th Century Fox, Yablans had begun The Demolished Man with De Palma at Paramount, where Yablans had been president from 1971 to 1975, presiding over the studio as it released the first two Godfather movies, The Conversation, Chinatown, The Parallax View, Harold And Maude, Serpico, Paper Moon, and The Day Of The Locust, among many others.

BAMcinématek in Brooklyn began a "Sunshine Noir" film series last night (Wednesday) with a screening of William Friedkin's To Live and Die in L.A. Brian De Palma's Body Double is included in the series, and will screen this Tuesday, December 2nd. The series "explores what happens when noir steps out of the shadows and into the neon-lit boulevards of LA," according to the BAM website. "Burrowing beyond the glitz and glamour of Tinseltown, these hard-boiled tales of outsiders and antiheroes expose the seedy underbelly of the City of Angels." There are almost too many great movies in the series to name them all here, but today and tomorrow, Roman Polanski's Chinatown will play, and on December 8 will be Paul Thomas Anderson's new film, Inherent Vice.

BAMcinématek in Brooklyn began a "Sunshine Noir" film series last night (Wednesday) with a screening of William Friedkin's To Live and Die in L.A. Brian De Palma's Body Double is included in the series, and will screen this Tuesday, December 2nd. The series "explores what happens when noir steps out of the shadows and into the neon-lit boulevards of LA," according to the BAM website. "Burrowing beyond the glitz and glamour of Tinseltown, these hard-boiled tales of outsiders and antiheroes expose the seedy underbelly of the City of Angels." There are almost too many great movies in the series to name them all here, but today and tomorrow, Roman Polanski's Chinatown will play, and on December 8 will be Paul Thomas Anderson's new film, Inherent Vice.The cynicism of “Chinatown” opened up the floodgates for a new strain of bitter Sunshine Noir. But there were also increasing levels of pollution and the emergence of postmodern architecture in Los Angeles (the glass cylinders of the Bonaventure Hotel were constructed between 1974 and 1976) that made the city feel more inhuman. As we crossed into the 1980s, and the former Governor of California was the President of the United States, Sunshine Noir took the city’s nickname, “The Big Orange,” quite literally. William Friedkin’s “To Live and Die in L.A” (1985), screening on November 26, presents a city cast under an atomic tangerine sky as if illuminated by a Dan Flavin fluorescent glow. Demarcated lines of good and evil were completely eroded, with police officers performing robberies and artists counterfeiting money in their painting studio. Jim McBride’s pop-art remake of Godard’s “Breathless” (1983), screening on December 4, takes place in a candy colored Los Angeles where past and present, the Hollywood myth and the tarnished reality, have collided. Both films end ambiguously, portraying Los Angeles as an inescapable landscape of continual violence.The first sign that the bitterness of the post-“Chinatown” era of Sunshine Noir was mutating once again was Brian De Palma’s “Body Double” (1984), screening December 2, which used John Lautner’s Chemosphere as the swank bachelor pad of the main character, a struggling b-movie actor, and the site where he witnesses a murder. The new sanitized Los Angeles of glass buildings is just a veneer for the city’s inherent seediness, where blood can still stain your minimalist furniture. Michael Mann’s "Heat” (1995), screening on November 6, is the prime result of this shift. The bloated crime drama fully takes place in this Los Angeles, where crimes of passion have been completely erased by crimes of commerce — everything is a transaction, everything is business. Criminals and cops can sit down for a meeting at a diner and nobody blinks and eye. They are practically interchangeable, and both sides have shootouts in the business district wearing Versace suits. Sunshine Noir takes on a different meaning here. The light of Los Angeles is a false light, illuminated from the inside of sprawling towers. A different, softer glow, but nothing has changed.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Inherent Vice” (2014), screening December 8, opens up a new chapter, once again looking to the past. Adapted from the novel by Thomas Pynchon, it presents a vision of Los Angeles that has not stopped believing in its own myths but completely wigged out on an overdose of them. Hippiedom is just another variation of the tangled lie of prosperity, and Pynchon’s world is one of confusion and paranoia. This is Sunshine Noir pushed to absurdist proportions, where the most far-fetched conspiracies suddenly seem possible, and the rotten core of the municipality stretches beyond the city limits. But it’s also the Sunshine Noir that speaks to our present condition. Take a look at the news and you’ll realize it’s closer to the truth than you want to admit.

-------------------------------

Ute Bergk, the set decorator on Brian De Palma's Passion, was interviewed recently by Travis Bean at Film Colossus. Bergk's work on Passion was the main focus of the discussion. Discussing how production on the film was on-and-off for years, Bergk tells Bean, "There was a point where [De Palma] was thinking, 'Oh, we’ll do it all in London.' And then I mentioned all the cars would be driving on the left side, and he didn’t like that at all."

Ute Bergk, the set decorator on Brian De Palma's Passion, was interviewed recently by Travis Bean at Film Colossus. Bergk's work on Passion was the main focus of the discussion. Discussing how production on the film was on-and-off for years, Bergk tells Bean, "There was a point where [De Palma] was thinking, 'Oh, we’ll do it all in London.' And then I mentioned all the cars would be driving on the left side, and he didn’t like that at all."DURING THE OFF TIMES, DE PALMA REWORKED HIS STORYBOARDS, HAD EVERYTHING ALL PLANNED OUT

Discussing how she came to be the set decorator on Passion, Bergk tells Bean, "The Production Designer Cornelia Ott, who is a friend of mine, she got the script and got me involved, and we budgeted over and over and over again, because they couldn’t make up their minds where they wanted to shoot, and they had certain actors in mind that didn’t kick in at the right time, at the right point.

"So it was at least over a year before we got storyboards from Brian De Palma. Which were brilliant! He does them all himself. And it’s like a Bible. Because the film took so much time to kick off, he worked them over and over again, so when the filming finally started, it was so straightforward. He had it all planned out. It was fascinating. It was really precise.

"He’s one of these directors that just knows: he’s coming in in the morning, he’s not saying anything, and he’s working with people who he trusts for whatever reasons, and he’s just watching them work for a little while, and then he asks if everybody is ready, and he starts to shoot."

"HE KNOWS EXACTLY HOW THE ROOM WILL BE SET UP BEFORE HE GETS THERE"

A little later in the discussion, Bean asks, "So if Brian (is it OK if I call him Brian?) is coming on set and not talking to many people, is he talking to you? Or is it pre-planned, where he’s talking to you beforehand? Or is it more organic, where you get there and set things up?"

Bergk replies, "It’s very planned. He never arrives anywhere without expectations. He knows exactly how the room will be set up before he gets there. We would present it all in little models or sketches or photos. And for every location he would have a little folder, and we would explain, 'This is the sofa she sits on,' etc. Like in one of the offices, where you see the white arrangement of very sophisticated white leather sofas: 'This is where the Japanese board is going to sit.' Very rarely will he say, 'Oh, I don’t like this at all.' It’s usually the other way around. And because the arrangements are so classic, you kind of go that route and not allow yourself to be off stylistically. You don’t want to go overly pop, or overly sophisticated."

"YOU HAVE TO FIND JUST THE RIGHT STANDING LIGHT TO PLACE NEXT TO ISABEL'S BED"

In one enlightening passage of the interview, Bergk tells Bean about meeting with cinematographer José Luis Alcaine: "I remember that Jose came in, and obviously we did not know each other when we started, and that working relationship came into play very quickly. Because the moment Noomi (Rapace, playing Isabelle) was confirmed for the film, I got a call saying, 'We start prepping ASAP.' Now basically.

"And I said, 'Really? Finally?!'

"And of course, off we went, and Jose came in. José was always trying to discuss things with Brian, which was quite funny, because Brian would always make excuses, like, 'I’ve got to go to the dentist.' Because I think Brian totally trusted him and what he was going to do. So he didn’t want to control him whatsoever. And that was great. That’s why it was so good to work on this movie, because there was freedom.

"And so, I had this long meeting with José and went through all the practicals, which was quite important for the whole film, because, at that point, I wasn’t very knowledgeable of Brian De Palma and unaware of how important all of that is. Because there are sequences, for example, where the entire scene is basically lit by the practicals. And if you see the two different offices (Isabelle and Christine, played by Rachel McAdams), one is white, and one is white-and-black. And if you look closer at what there is in terms of practicals, it’s totally different.

"We had this glass desk in Christine’s office because we wanted to see her legs. And it’s all very sexy and round…and a bit bitchy. Isabelle’s office is the other way around: it’s all very cruel, almost frozen. You see this black, bold standing light in the background, which is pretty much what I thought was her. And it’s a very complicated light fitting because it’s lit in a very complicated way, but José liked it because, for all the dream sequences, he used this black-and-white lighting, which that light fixture naturally gives him.

"And that was a very interesting discussion! I’d never had that before. But obviously that was so important for the whole film. The more time you spend with these guys, the more you get into it. You learn what’s important, that you have to find just the right standing light to place next to Isabel’s bed during her dream sequence. That took me weeks to find!"

"IF YOU WORK WITH BRIAN DE PALMA, YOU KNOW THAT YOU HAVE TO HAVE MIRRORS"

When asked by Bean where she went to find decorations for Passion, Bergk replies, "It depends where you are. Passion was shot in Berlin, and we didn’t shoot many sets in the studio. We built a few additions to existing locations, and we’d incorporate architectural details. But the thing with Berlin is: it’s not such an advanced industry, as it is in London [where Bergk resides]. Berlin does not really have facilities.

"So, for Passion, it was all very contemporary. It’s not like you had to do lots of research into some period details. It was contemporary, it was very classic. If you work with Brian De Palma, you know that you have to have mirrors. You will see the ceiling, which is very unusual, because a lot of directors don’t show the ceiling in movies at all. So that’s a very interesting research subject actually: who is looking up in the film?

"And because the style was contemporary, most of the stuff you see is available in shops. It’s very high-class furnishing. In the first scene you see a sofa in Christine’s apartment, and that’s one I had made, which was possibly the most expensive piece of furnishing in the entire film. But I thought it was worth it—there was something existing and I adopted it, changing its color and shape. This kind of film is not rough. It’s a very delicate film.

"There’s this nice sequence where they’re sitting in front of a huge television and a character gets drunk, and he gets drunk on a Fendi, a luxurious settee—and it is so uncomfortable. I saw it in an exhibition. To sit on it is fine, but to get drunk on it is very uncomfortable. It’s not like a sofa that you fall into. And he was supposed to fall into it, but he couldn’t because it has wooden a frame. So when he does fall into it, he makes this sounds like [insert uncomfortable *oomph* sound effect], which is exactly what was needed for this sequence. So that was a good find."

THE BALLET SEQUENCE

The interview ends with a discussion of the ballet sequence in Passion:

Travis I feel obligated to ask about the ballet sequence, just because it makes me giggle with excitement every time I watch it. I know in the actual ballet studio, there isn’t a lot in there, it’s mostly blue and white walls. Did you contribute anything specific to that sequence? Working with the idea that it would be displayed partly on a split-screen? Or that there would be a lot of empty space to deal with?

Ute Bergk It was actually more of the other way around. I sent you a video, did you get it?

Travis Yeah yeah, I watched it!

Ute Bergk That was the original version of the performance. There’s a foundation behind it, and you are very much controlled by this foundation. The choreographer came over from the States and she was very controlling about everything. If you see, in the black and white footage I sent you, in the beginning, the curtain is on a pole and goes up, above the stage, which is where we shot. It was quite difficult to do, because we had this theater setting and everything just goes up, and not up and around. And we had to do it that way. They had to see that pole going up. So we had to build a structure to do that with.

Basically, you have to find the right materials. We had to slim it down because we shot it on a quiet part of the stage, which is in the Renaissance Theater, which is not big at all. So there was a model built that was put into this existing space. And to drape white fabric without having any frills in it is not easy.

The whole ballet sequence—we knew it would be very important, so we shot it for three days in that theater with those two wonderful dancers. And it was crystal clear that the stage design at that point was part of what the story tells. And specifically, in that performance, the audience is the mirror. They dance behind their exercise rails to warm up, and what is behind is basically nothing. It’s like a rehearsel room. And all you see is the door they come in and a window. And that’s all. The rest is up to them. And that was as simple as is. Brian, at that point, was just focused on the dancers.

Travis Well definitely. They’re looking right into the camera, and effectively looking right at you. I’m fascinated by that aspect of the film. Not only the characters are being watched—he’s looking right at the audience and acknowledging their presence in the movie.

Ute Bergk It was a very artistic approach, obviously. To have the audience as the third part, see that in certain kinds of artwork, like Manet’s paintings for example. The artist plays with the subject as well. So it’s very interesting to address it in that way—it’s a very De Palma style of filmmaking to address the audience. And then the split screen…I still get goosebumps thinking about it.