From Daniel Kasman:

"But the real film legacy project here at TIFF is Brian De Palma's Passion—for me, the film (or, actually, video) of the festival so far. It is an old man's movie par excellence, taking film history as the subject of a work of cinema that would better fit within the context of the experimental works in the Wavelengths section than in the multiplex in which it was shown, seemingly baffling an audience expecting a semblance of realism from the screen. Its oldmanness is the deep, precise pursuit of the conventions of the cinema De Palma has been engaging with for the length of his career, and thereby engaging his career itself.

A remake of the solid Alain Corneau corporate thriller Love Crime, De Palma plunges without hesitation into the iconography, audience expectations, and conventions of noirs, sex thrillers, corporate intrigue, post-Hitchcock films and Brian De Palma movies themselves, retaining the shell appearance of all of these things but hollowing them from the inside out. The result is something out of late Resnais—a study of a study. And that study, of course, is of the cinema image. Remember how Rebecca Romijn watches Stanwyck in Double Indemnity at the beginning of Femme Fatale, as if taking notes? The characters in Passion have taken notes from Femme Fatale: an abstraction based on a fiction based on a fantasy. It is complex, dextrous, and awkward: Rachel McAdams plays and acts the seductive, power hungry blonde in a performance that is like a kabuki imitation of the type; Noomi Rapace is her underling, friend, object of love and obsession, our heroine and, therefore, at first, directed to act “normally.” (This film's skewering of cinematic female friendship is twisted, sinister, cynical and terribly interesting.) Like in Paul Thomas Anderson's The Master, but far more knowingly, cleverly, the director is here forcing a confrontation between two entirely different acting styles and kinds of characters. In Passion, one is ostensibly a hollow signifier, the other our, the audience's, psychological subject, person of empathy. Except the film, lurchingly structured in three fascinating sections, with the middle one styled radically differently, introduces a third character, another woman (which brings the collection to: a blonde, a brunette and a redhead), who begins to appear more normal as Rapace's character enters deeper into the story and begins to be abstracted by the movements and conventions of her plot. We lose our focus on one as another comes in. Where the film leaves us, after developing this schema and then following its "thrills" to the end, is truly disturbing.

I feel like I could talk about this movie forever—it comes so welcome after, in Cannes, suffering through the shockingly disrespectful cultural and cinematic ignorance on display in another ostensibly generic, and homage filled film, John Hillcoat's deplorable Lawless. De Palma's film is suffuse with a deep knowledge film history and aesthetics, and, in yet another remarkable engagement with digital video (after his first foray in his last film, Redacted), has constructed a film that questions our expectations, understanding, interest, empathy and perspective on them. The lucid, confrontational clarity of the digital images renders the film's hermetic artifice—despite being often photographed on location—even more dissonant, heightened and abstract. The archness of the film is absolute. It is a work of cinephilia but one which remarkably takes the form of a step forward—it's an object that exists in the continuum of the subject that it is studying.

I know you liked this film too, so I'll perhaps let you take the baton from my ramblings, because I haven't even begun to talk about De Palma's use of video in this, his close-ups which appear like nothing else in the festival, his total understanding of what's interesting in Rapace's face, of the startling falseness of McAdam's sub-Dressed to Kill simulacrum, the film's perverse and knowing humor and absurdity, its roleplaying, the images within images (him and Ferrara both, loving Skype video calls!), including a mini cellphone cam movie that is pure De Palma and also an advertisement for jeans. What else, what else? Oh, to leave you with another favorite: the film's one split screen sequence, a magnificent anti-set piece, yet so clever, placing a ballet performance in one screen with uninteresting plot mechanics in the other—only to culminate in a murder. Can you tell I'm excited? This film is strange and rich. I'm sorry I can't be more coherent and structured in this, as it appeared a lot of people didn't like if not downright hated or laughed at this movie, which I think is a mistake."

And then from Fernando F. Croce:

"Ah, Passion. Perhaps not the film of the festival for me (that’s still Like Someone in Love), but certainly the one that most tickled my cinephilia. Like Kiarostami’s film, it’s a wondrous feat (a series of feats, really) of misdirection. Who are these characters who look like Rachel McAdams and Noomi Rapace and Karoline Herfurth but are actually gimlet-eyed projections from cinema’s past? Abstractions, sure, yet when do abstractions exude such a feeling of heated flesh, of shards of fantasies being moved around the screen like drops of mercury? The layers upon layers of De Palma’s artifice dare us to find out. It’s a crazy, thorny spiral of a movie, not “campy” but funny. Think of McAdams, done up like a parody of Grace Kelly (her blonde hair for some reason looking like a wig) in her wood-paneled office with the word “IMAGE” spelled in red, blocky letters behind her. Or of Rapace ramming her car into a Coke machine (De Palma’s Godardian side is always present), followed by a crying jag and a sudden rain that are, like everything on screen, not what they seem. (A camera movement reveals the fire-alarm sprinkler drenching the character from above, and, of course, the security lenses recording it all.)"

Updated: Thursday, September 13, 2012 8:14 PM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

Rachel McAdams and Eli Roth are pictured here from earlier today (Tuesday) at the Variety Studio at TIFF. McAdams did participate in an interview while there, so hopefully this means she will be on the

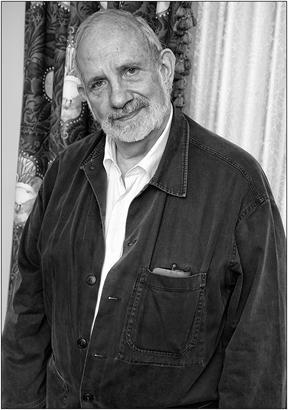

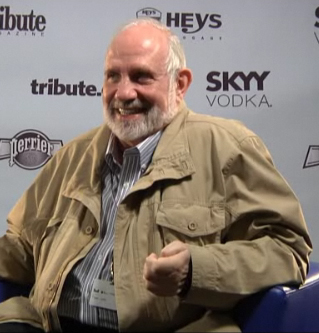

Rachel McAdams and Eli Roth are pictured here from earlier today (Tuesday) at the Variety Studio at TIFF. McAdams did participate in an interview while there, so hopefully this means she will be on the  The picture here is from Toronto on Monday, but the interviews in this story happened at Venice. First, the picture: Brian De Palma at the Hollywood Reporter's TIFF Video Lounge.

The picture here is from Toronto on Monday, but the interviews in this story happened at Venice. First, the picture: Brian De Palma at the Hollywood Reporter's TIFF Video Lounge.