The Dresden Maya Codex

The Dresden Maya Codex

1.

The History of the Dresden Codex

The Dresden Codex

is one of the most valuable sources for understanding the Maya culture. This

manuscript was one of the most important keys for the decipherment of the Mayan

hieroglyphic writing. Furthermore, the most beautiful and famous figures of the

Maya gods also arise from this codex. The Dresden Codex takes its name from the

place where it is found today – in the Saxon Library of Dresden, Germany.

With some confidence, we can reconstruct

the history of this unique manuscript, which by some historians is considered

the most important prehispanic manuscript of the Americas. Most probably in

1519, the famous Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortéz sent it personally to Madrid,

to the court of the then king Charles the fifth, together with other curiosity

items. In addition to these, there were other more common items of

treasure. Somehow the codex was brought from Madrid to Vienna, where the king

had one of his residences. The codex remained there without being given any

consideration until in 1739 it was discovered in a private collection by Johann

Christian Götze, who at that time was the director of the Royal Saxon Library

of Dresden. The codex was obviously given to Götze by its unknown owner, who

must have considered it to be of no value, since he could not understand any of

it. Götze, however, donated the codex to his library at the beginning of the

year 1740.

2.

The Origin of the Dresden Codex

In 1519 Hernán Cortéz navigated along the Yucatán

coast, between Cozumel and Zempoala. Therefore we can assume that the codex

originally came from the Yucatán peninsula. This assumption is also based on

several varying hieroglyphs found in the codex corresponding to languages which

are spoken in Yucatán, and not in Chiapas or Guatemala. Furthermore, on the

basis of the extensive astronomical information contained in the codex it is

agreed by many experts that the codex originated in Chichén Itzá. We can place

the codex in the postclassical Maya period, around the year 1250. There are

some writing errors in the codex, however, which demonstrates that passages of

the codex had been copied from ancient manuscripts. Dates shown in the codex go

back to the classical period.

3.

The Production of the Maya Codices

Up to now, there

are only three known Maya codices, those of Dresden, Paris and Madrid. All the

known Maya codices are made of amate paper. The Maya and other Mesoamerican

peoples obtained this paper from the bark of the wild fig tree (ficus cotinifolia).

The bark was boiled in water until it became tender. Afterwards it was put in

strips on a wooden board; each strip being laid next to the other. The strips

were then stretched out, and pounded with a smooth stone. This process resulted

in producing a type of paper because the fibers became joined together, like in

felt material. Finally, the piece was left simply to dry in the sun. A lime

coating was added to the piece. In this way the smallest details could be drawn

on the finished product. Once finished, the amate paper was folded in the shape

of an accordion. Likewise the strips were joined together with a special glue,

made from orchids and other plants, to form a longer codex. The longest Maya

codex is the Madrid Codex with 115 pages, measuring 6.80 meters. The Dresden

Codex is made up of 39 pages, each one measuring 9 x 22 cms, and containing

drawings on both sides, excepting 4 pages, which have been left blank. This way

the codex contains drawings on 74 pages in total. The codex measures 3.56

meters in length, making it the second longest Maya codex.

4.

The Content of the Dresden Codex

The majority of the Maya codices are about

religious topics, but they also contain some pages that describe historical and

astronomical events. The Dresden Codex can be divided into several chapters. It

contains a ceremonial calendar for the different gods, the famous tables of

solar and lunar eclipses and tables for calculating the movements of the

planets Venus and Mars. Also described are ceremonies for the beginning of the

year, a big flood, and a prophecy of a Katun (a 20-year-period in the Maya

calendar).

5.

The Present Reconstructed Version

This new Dresden Codex is a reconstruction.

Those who know the different editions of the codex are aware that the original,

regrettably, is badly damaged. Above all, the thin stucco coating in the

corners has worn off. Therefore it is clear that a complete reconstruction of

the codex is not possible. It must also be mentioned that the images of the god

figures have faded during the last 800 years. For the purpose of this edition,

the pages 4 to 15 of the original codex have been redrawn. All the original

positions of the figures have been retained. The numbers and hieroglyphs of the

days were newly calculated where they had been erased, according to the logic

of the Maya calendar.

6. The Description of the Codex

In this codex we see some of the most beautiful and

well-known Maya gods, just as they are represented in the Dresden Codex. The

pages of the codex act as an almanac that describes the days of the Sacred

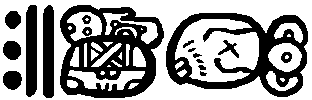

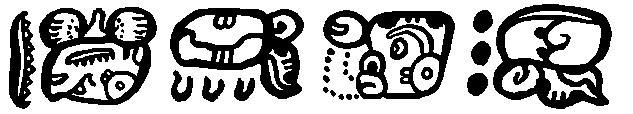

Calendar on which the gods carried out their rituals. Each table began with a

column of 5 hieroglyphs that represented some of the 20 days of the Sacred

Calendar of 260 days. Above this column we find a number in red. To the right

of this, there are numbers in red and in black. The numbers in red are always

ciphers. Only 13 are found. The red numbers are coefficients of the 20 Sacred

Days, while the numbers in black represent the number of days elapsed between

two dates.

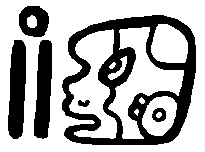

![]() 0

0 ![]() 1

1 ![]() 5

5 ![]() 20

20

Above the representations of the gods there are

hieroglyphs found that form short texts which describe the corresponding

scenes.

7. The

Description of the Maya Gods

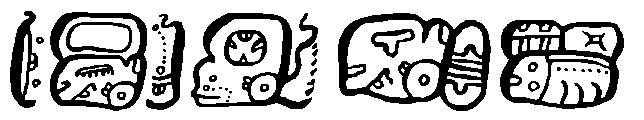

The reader will next encounter a small description of

the Maya gods. The hieroglyphs shown here correspond to the names of the gods. The

numbers behind the names of the gods indicate where this god can be found in

the codex. For example, in this codex the jaguar has the position 5A2, which

means: page 5, top part, second figure. The letter B indicates the middle part,

the letter C the bottom part.

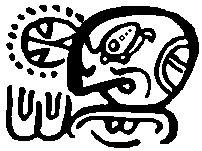

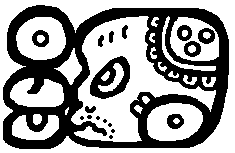

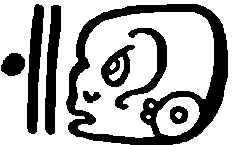

Itzamná (1B,

3B1, 6B)

“Itzamná” – “the wise shaman or magician” – is the

highest-ranking Maya god. For many Maya he is known as the father of the gods.

He is represented with a hooknose and volute-shaped tears. Itzamná is the creator god and god of medicine. The god Itzamná is an old and wise god that

resides in heaven. The shamans and calendar priests, who predict the days of

fortune or bad luck, receive their wisdom from Itzamná. Itzamná is not

only the inventor of the complicated Maya calendar, but also of the

hieroglyphic writing. On the first page of the codex, Itzamná is emerging from the jaws of the celestial dragon.

Zak Kolel (11C2)

Zak Kolel means “maiden”. She is the goddess of love. She is

recognized by her long, untied hair that curls over her naked body. Maya

artists frequently show her in love scenes with other Maya gods in the Dresden

Codex. She also represents the waxing moon. As the moon is growing, so is the

stomach of a pregnant woman. The young goddess of the moon is also the goddess

of medicine. In the Dresden Codex, she appears many times with different birds,

which are omen for illnesses.

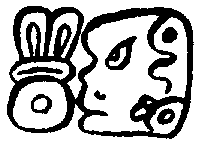

K’in Ahau

(1C1, 9C3, 12A1)

Kin Ahau means “lord of the sun". The hieroglyph k’in is also seen on his arm. The sun

god is the only Maya god shown with a beard. In the classical inscriptions he

is also recognized by his filed tooth. His head replaces the number 4 in the

inscriptions that contain dates. The god of the sun is also called K'inich Ahau, which means “the sun-faced

god”.

Naal (6A3,

8B2, 9A1)

The maize god is one of the most worshiped Maya gods. The wellbeing of

the people depends on his mercy. Maize is the most important plant for the

Maya. The Popol Vuh, the Mayan bible,

relates how the Maya people were created from maize. The name of the maize god

was Naal and Hunal-Yeh, which mean “maize sprout” and “reincarnation of the

first maize sprout”. The maize god is sometimes erroneously shown as Yuum K'aax. Nevertheless, this name was

never used to designate the maize god (or any other god). The expression yumil k’axob – “lords of the wooded

mountains” refers to the spirit protectors of the mountains, and has nothing to

do with the maize god. The confusion began with Sylvanus Morley, who did not

know the name of the maize god. In his book “The Ancient Maya” he mentioned for

the first time a “Yum Kax”. Since that time the error has been copied over and

over again. The maize god is easily to recognize with his head decoration in

the form of a maize sprout. As a numeral god, he represents the number 8.

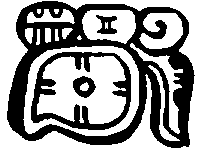

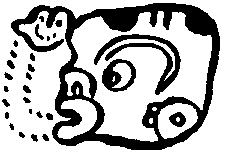

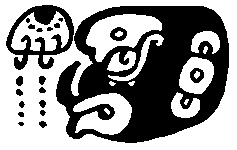

K’uk’ulkan

(3A2, 4C3, 9B2)

K'ukulkan, or Kukulcan

in traditional writing, is a foreign god that does not appear within the Maya

until the postclassical period. In his name glyph we see a sign in front of his

head that represents a plum of feathers - in Maya: k'uk'ul. In the head we see an element represented with small

circles, which is also seen in the hieroglyph of the day Chic-chan, which means “snake” or “serpent”. (In the Yucatec Maya

of today it would be kan instead of chan). These two elements together: k’uk’ul kan – “feathered serpent”. Among

the Aztecs this god is known as

Quetzalcoatl. K’uk’ulkan is a

Venus god. As an opponent of the Aztec god Mictlantecuhtli

he is also called the “god of life”.

Xaman Ek’

(2A2, 10B3)

Xaman Ek’ is the god of travelers. Xaman Ek’ means “north star”, like the polar star that guides the

traveler at night. He is recognized by his monkey face. He surely represents

the howler monkey the Maya considered sacred. For this reason the glyph also

reads k'ul, which means “sacred” or

“divine”. In texts, his name glyph is used many times as an adjective for the

names of other gods. Xaman Ek’ is a

celestial god. In the Maya codices he is always shown in the sky, and never on

the earth. The howler monkey likewise stays in the canopy of the jungle and

rarely descends to the ground.

Chaak (7B1,

8B3, 12B1)

The god of rain Chaak

is easily recognized by his long hooked nose. His name means

“rain” and also “giant”. This is the god most often depicted in the Maya

codices. As with other Maya gods, this one can be subdivided into several gods.

So it is that he is sometimes seen as a quadruple god representing the four

cardinal points. The red Chaak is

sitting in the east, the yellow Chaak

in the south, the black Chaak in the

west, and the white Chaak in the

north. The god of rain is usually seen with an ax in his hand, which he uses to

cut the clouds to liberate the rain. With his torch he creates lightnings.

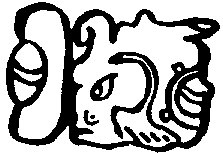

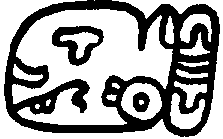

Chaak Balam

(5A2)

The Maya have several zoomorphic gods. The most

important animal god was the jaguar. Chaak

Balam means “big jaguar”. Sometimes it is decorated with a water

lily, since jaguars usually like to be around water. The jaguar is both feared

and venerated, and its strength and elegance has served as a symbol of power

since primitive times. This powerful and elegant animal has been a symbol of

power since early times. The Maya king is often seen on a two-headed Jaguar

throne. The Maya also associated the jaguar with the sun of the underworld. The

Olmecs believed its people to have originated from the union of a human woman

with a jaguar.

Bolon Tz’akab

K’awil (9A2)

Bolon Tz'akab

K’awil is one of the most important gods

of Maya origin. In the classic period this god appeared as the god of the

scepter. He is recognized by the fact that one of his feet transforms into a

snake. Also his forehead is represented as a mirror on which a smoking ax is

buried. K’awil means

“personification”. Bolon Tz'akab

means “9 generations”. The god K’awil

personifies the union of the elite Maya with the power of ancestry. The most

famous representation of K’awil can

be found on the lintels of Yaxchilán.

The god K’awil of the late classic

period is recognized by his big nose. He is also regarded as the god of

fertility.

Kuy (4C2, 7A1)

The owl Kuy

is a symbol of war. Her shout announces an imminent battle. The name Kuy was used as a second name by several

Maya kings when they considered themselves as triumphant warriors. See the

famous ruler Pakal of Palenque.

Kimi (7C1,

10A2, 10B1)

The god of death Kimi is easily recognized by his

skeleton. In the highlands of Chiapas this god is also known as Ah Puch. In Yucatán, however, this name

has never been evidenced.

Lahun P’et

(3B2, 5C2, 7B2)

Lahun P’et means “ten sacrifices”. He is the god of

human sacrifices. The decoration in his ear is a jaguar tail. The dots pictured

on his body represent the skin of a prisoner that has been removed and which he

has put on. He is the counterpart of the Aztec god Xipe Totec.

Buluk Ch’abtan

(2B2)

Buluk Ch’abtan means “Eleven fastings”. He is the god

of hunger and deprivation. He is also represented in the production of the New

Fire.

H’obnil (4A1,

11C2)

H’obnil is the ruler of the underworld. His name

means “sudden death”. He is recognized by his black body painting and his

elaborate headdress that features the owl Muan.

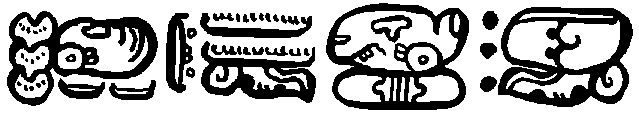

8. Examples of

Hieroglyphic Texts

(5B)

[u] nuch hol kimi

oxlahun kuy

“They are conversing, the god of death Kimi and the owl of the 13 heavens”.

(7B1)

ochiy u kakaw

chaak ox ok wah

“The god of rain Chaak

is rattling the cocoa seeds. Abundance of food [is the prophecy].”

(10B3)

u

mak’ wah xaman ek’ ox ok wah

“The god of the

polar star Xaman Ek’ is receiving

food in the form of maize. Abundance of food [is the prophecy].”

(10C2)

k’uch yatanil

tzul ...

“The vulture woman is marrying the dog man....” The

meaning of this strange marriage is unknown to us. Possibly, there exists some

astronomical constellation.

(12B1)

u pak’ah tzen chaak ahaulel

“Our ruler Chaak,

the god of rain, is planting the nourishment.”

→

back to main page Mesoamerican Codices