HomePort

|

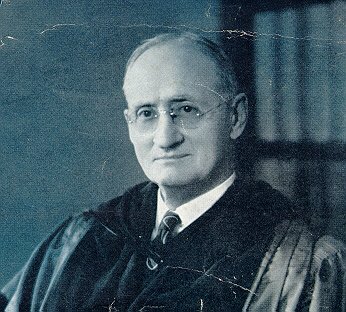

Dr. Walter Dill Scott |

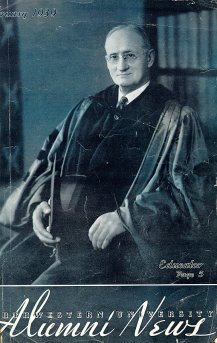

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY'S most distinguished alumnus and one of the nation's greatest educators will retire from active administration next September when the beloved President Walter Dill Scott assumes the title of President Emeritus.

The history of the University's tremendous growth during the last two decades coincides with the presidency of Walter Dill Scott-and what the University would have been today had another president guided its destinies during those years, no one can say. To the Northwestern University of 1939 might well be applied Ralph Waldo Emerson's oft-repeated assertion: "An institution is but the lengthened shadow of a man."

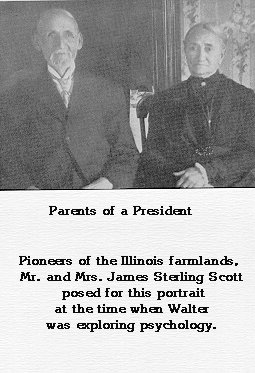

The man in this case is Walter Dill Scott, and thus this is the story of Walter Dill Scott, but its beginning, cannot be told apart from that of his elder brother, John. The boys-and their three sisters-grew up together on their father's farm at Cooksville, in central Illinois. From the hill on which their farm lay they could almost see Illinois Wesleyan, where their mother, a teacher before her marriage, had gone to school. Their mother's uncle was president of the college.

Their father, James Sterling Scott, had

been a member of his family's carriage-manufacturing firm in Boston.

But the work had been unsuited to a man of his delicate constitution, and

he had left the firm to come west in search of health. At Cooksville

he had taken up a government claim, married Henrietta Sutton, and settled

down to the life of a farmer.

The farms of central Illinois were of a kind. A hundred twenty to a hundred sixty acres in extent, each could be made to yield a moderately comfortable living if every member of the family worked hard and long. Consequently, like the children of the neighboring farms, each of the Scott boys began his farm duties as soon as he was able to lift a pail or sit upright in a jolting wagon. The boys learned farming perhaps faster than the sons of other families, because their father's poor health imposed many responsibilities upon them. When Walter was eleven, for example, John left home for a few months to work on the Illinois Central railroad line which was being constructed between Cooksville and Bloomington, and Walter was left in complete charge of the farm. He took the grain to market, sold it, traded cattle, broke a colt when necessary, kept accounts.

The boys were determined to become teachers. They pursued learning diligently, if sometimes in the most informal circumstances. The nearest high school was at Normal, twelve miles away, and Walter managed to attend class for perhaps a year and a half; when he could not attend formal classes he found time to study his Latin while the horses rested and he leaned against the plow.

In 1888 John left the farm for Northwestern University. Walter continued to study, to manage the farm, and to save money for his college education.

His college fund had been begun when he was a small boy. A neighbor had presented him with two orphan pigs. These he had raised by bottle-feeding, and when they were full-grown he had traded them for a calf. Later he traded the calf for a colt, which he trained as a fast trotter. The sale of the trotter contributed $125 to the fund.

In 1890-91 he held his first teaching job.

During the first term he taught the country school in Leroy, Illinois;

during the second he taught in and served as principal of the school in

near-by Hudson. He added his salary to his college fund.

In the summer of '91, having been awarded a senatorial scholarship, he drew his careful savings from the bank and departed for Evanston.

Almost upon his arrival the youth from the farm entered into the elite of those who work their way through school: he became, as John had been before him, a tutor of the children of the rich. He asked, and received, a dollar and a quarter an hour for his services, for which there was frequently more demand than he could fill. He tutored only enough to pay for the things he needed. He seldom cashed his checks-he simply traded them.

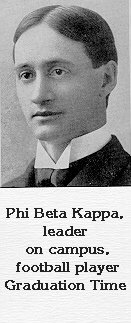

Walter was a top-ranking student, and a leader in campus activities as well. He served as treasurer of his freshman class, president of the Y.M.C.A., president of his senior class, member of the editorial staff of the Syllabus, and vice-president of the literary society, and played left guard on the varsity football team.

A tall, lean youth, he had not been heavy enough to play in all the football games during his sophomore year. He was disinclined to miss any of the experiences a college career might afford, however, so in the summer before his junior year he determined to prepare himself for the following fall. For one month he tutored eight hours every day, with the money he earned, he went to Colorado, where by assiduous mountain-climbing and other strenuous activities he toughened his muscles. The following fall he played in every game.

Of those years on the varsity he still bears a memento: a crooked little finger. During one of the early games of his junior year he broke the finger but disregarded the injury so that he could continue playing. As a result of the persistent battering his finger received in the games that followed, it never set properly.

Walter Dill Scott received his bachelor's degree and Phi Beta Kappa key at Northwestern in 1895. Some time during his college career he had decided that he wanted to be a university president in China. This was not entirely a romantic notion. He regarded China as one of the greatest countries in the world. Its educational possibilities were limitless and he had the attitude of the educational experimenter. While a student in the high school he had taught kindergarten and had experimented in teaching methods. In his private tutoring he had devised methods to make the most effective use of his pupils' individual aptitudes for study. His year in the country school, with its assortment of boys and girls of all ages from six to twenty, and of every conceivable grade of intelligence, had given him considerable insight into the nature of the educational process. China, he felt, offered a rich field for educational experimentation.

The Chinese colleges were supported, for

the most part, by American religious organizations; therefore, to achieve

his objective Walter had to have some theological training.  Shortly

after his graduation from Northwestern he enrolled at the McCormick Theological

Seminary (though their parents were Baptists, John Scott was at that time

a Methodist and Walter a Presbyterian), whence he was graduated in 1898.

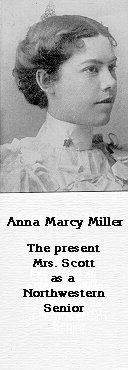

In this same year he married a dark-eyed, intellectual young woman who

had been his classmate at Northwestern—Anna Miller.

Shortly

after his graduation from Northwestern he enrolled at the McCormick Theological

Seminary (though their parents were Baptists, John Scott was at that time

a Methodist and Walter a Presbyterian), whence he was graduated in 1898.

In this same year he married a dark-eyed, intellectual young woman who

had been his classmate at Northwestern—Anna Miller.

No call was forthcoming from China. Besides, Walter had by now developed an additional interest—an interest in a new science which promised to contribute more to the techniques of education than any other: psychology, the science of the human mind.

The leading psychologist in the world at the time, the man who was divorcing psychology from philosophy and converting it into an experimental science, was Wilhelm Wundt, at the University of Leipzig. So Walter Dill Scott, taking his bride with him, went to Germany, one of the troop of promising young men who were leaving our shores for Europe to explore what was, at the century's turn, an exciting new field of learning.

In 1900 they returned, she with a doctorate in philology and art from the University of Halle, he with a doctorate from Leipzig in psychology and educational administration—and with a passion for measuring and analysing human minds. In 1901 he was appointed assistant professor of psychology and pedagogy at Northwestern and made director of the psychological laboratory.

At this time a new movement was arising in psychology in America—a movement to develop psychological techniques for the solution of problems in business and industry. That it met with opposition from academic circles is readily understandable. Psychology was then not long divorced, indeed not yet completely divorced, from that most academic of disciplines, philosophy. Furthermore, academic men were inclined to deplore, or to disregard, so far as they were able, the rapid industrialization and commercialization of America.

To Professor Scott, as to a handful of others,

such isolationism seemed artificial and futile. ln his eyes psychology

had nothing to gain but much to lose by disregarding that enormous and

turbulent creature which now dominated the country—Industry. The

phenomenon of mass production impinged upon the minds and bodies of men

at every turn. lt had fostered those two inescapable aspects of modern

life, advertising and salesmanship-phenomena directed toward human minds

and therefore toward the scientific attention of the psychologist.

Chapter 2

Walter Dill Scott was not long in turning his attention to the problem. In 1903 he published The Theory of Advertising, the first book in this field, and a few years later his Psychology of Advertising, in which he analyzed the stimuli that foster the will to buy, and laid down a set of scientific principles by which the probable effectiveness of any advertisement could be gauged before it left the advertising manager's office. This book was read in all the principal countries of the world. As late as 1931 a new edition, only slightly revised, was published.

From the study of advertising it was only a step to the study of the psychology of salesmanship and the broader field of vocational selection.

In time his contacts with various organizations convinced Professor Scott that their real problem in salesmanship was not with advertising copy but with the men they employed as salesmen. Most companies had employment managers, but in nine cases out of ten, he discovered, their methods were hit-or-miss; they selected salesmen largely on the basis of "hunches."

Here was a new field to explore—and Dr. Scott explored it. For a two-year period he experimented with the employment of salesmen, first for a great tobacco company and then for several other large organizations. Every Saturday the employment managers of a number of large Chicago concerns met at Northwestern, and each of them, under Dr. Scott's supervision, interviewed a large number of applicants for positions as tobacco salesmen. Their methods of interview and the responses and attitudes of the applicants were methodically recorded. Then an elaborate record of the degree of success achieved by each applicant was kept. By an analysis of the two sets of records—the interviews and the sales history—Dr. Scott constructed a system of tests of vocational aptitude. These were then used as the basis for hiring new salesmen, and the results obtained by the new group of men were tabulated and analyzed. The tests were then revised. Rapidly, in the laboratory improvised at Northwestern by Professor Scott, the job of employing men in industry changed from a hit-or-miss ordeal to a systematic technique. The employment of industrial personnel approached a science.

Interest in the new science grew rapidly,

and in 1916 Carnegie Institute of Technology organized a Bureau of Salesmanship

Research, designed to discover how scientific knowledge could aid business.

Professor Scott was granted a leave of absence to serve as its director,

and soon, with the cooperation of thirty national concerns, had undertaken

a study of their methods of selecting, developing, and supervising their

employees.

The following year, however, the United States entered the war against Germany and there immediately arose a personnel problem of such urgency and complexity as to dwarf any problem that had previously been attacked. A peaceful nation had suddenly to be converted into an army. A nation of farmers and grocers, accountants and barbers, bricklayers and jockeys had to be welded into a powerful military unit, and recruits assigned with the least possible delay to that branch of the service where they would be of the greatest value.

The part they might play in the gigantic mobilization was immediately apparent to Dr. Scott and his colleagues. Why, they reasoned, if they could develop a rating scale that would predict a man's success as a salesman, could they not construct others which would forecast success as a linguist, and officer, a member of the intelligence service? The members of the Bureau, therefore, unanimously voted to offer their services to the War Department and immediately set about adapting their rating scales for use by the army.

Army tradition was not to be easily overcome, however; their first proposal, one for the selection of officers by scientific methods, was returned from the great officers' training camp at Plattsburg with the notation, "The Commanding Officer will not be able to use this."

Chapter 3

But so assured of the practicability of their system were Dr. Scott and his colleagues that they were not to be dissuaded, and later in the same month their persistence was rewarded.

Frederick P. Keppel, then assistant to the Secretary of War, saw a copy of the proposal and asked for further data. Dr. Scott sent him a full explanation of the rating scale for selecting commissioned officers, whereupon Mr. Keppel submitted the proposal to the Adjutant General of the Army, Major General H. P. MeCain, and invited Dr. Scott to Washington to discuss it in detail with the authorities.

A test of the rating scale was arranged at Fort Myer, and was very favorably reported upon by the officers in charge. The next step was to obtain the acceptance of the scale at Plattsburg.

Here Dr. Scott faced a critical situation. The scale had already been refused by the commanding officer at Plattsburg. If it were to be rejected again all the work which had gone into its construction would be wasted and the method would probably never be used in the Army.

His reception at the camp was not encouraging. Dubious of academic theories, the commanding officer and the senior instructors criticized the scale severely. They spent hours debating its every feature. Finally, when their scepticism had been made plain, they gave permission for a practical test. It was decided to try the test on men who were admitted to be good officers; if it indicated aptitudes they were known to possess it could be assumed to be a fairly accurate gauge. To the amazement of the officials, it worked admirably and, converted, they immediately wired Washington to recommend that it be utilized at all camps.

The task of the committee which Dr. Scott forthwith set up and headed was threefold: to discover what types of abilities were needed in the army, to place each enlisted man where he had the opportunity to make best use of his talent and skill, and to select and promote officers on the basis of merit and ability.

The story of the extraordinary success of the scientific personnel methods is told in an official history issued by the government; by the time the war was over they had reached every branch of the Army, at home and abroad. They prevented such heartbreaking inefficiencies as occurred in the great British volunteer army, where accomplished linguists served as cooks, electricians peeled potatoes, and skilled shipbuilders curried mules.

They solved the problem of selecting not

only officers but also men whose aptitudes would fit them for training

as specialists and technicians of many kinds. They devised means

of keeping wartime industries adequately staffed. They made possible

successful selection of men for unusual tasks peculiar to a wartime army.

The major credit for this work has been officially bestowed upon Dr. Scott. The Distinguished Service Medal which was awarded him at the conclusion of the war was accompanied by this citation:

"Colonel Walter Dill Scott, United States Army (discharge). For especially meritorious and conspicuous service in originating, organizing, and putting into operation the system of classification of enlisted personnel now used in the United States Army."

Following the Armistice, when two million soldiers were detained in France owing to lack of transportation, the Army chiefs determined to help these men to study and improve themselves. Again Dr. Scott was called into action, and within a short time he organized a system of vocational training for the soldiers to follow while they awaited transportation.

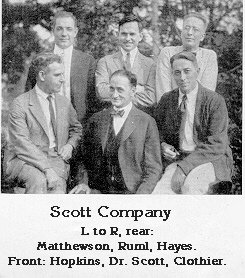

Shortly thereafter, he returned to his post at Northwestern, and immediately entered upon another venture—the formation, with a group of men who had worked with him in the Army, of the Scott Company, a research and consulting agency in the field of industrial personnel.

During the war many new principles of testing,

selecting, and classifying had been worked out. Dr. Scott was eager

to apply these to industrial problems; the new company was consequently

organized for the purpose of assisting employers, through research and

consultation, to develop the technique and procedure for their use.

Within a year the group gave assistance to more than forty industrial and

business concerns, including meat packers, banks, manufacturers, department

stores, insurance companies, and public service organizations.

For Walter Dill Scott, however, the venture was to be short-lived. In 1920 he received the offer of the presidency of Northwestern University.

He tells a characteristic anecdote concerning the invitation:

"Modesty prevents me from telling how this happened, and in fact it is not necessary, because at a faculty meeting following my election my brother, John, explained it. His words are practically as follows: ‘Walter and I saw that Northwestern University was compelled to appoint a new president, and we decided to attempt to secure the position for one or the other of us. Walter agreed to exert his influence for me, and I agreed to exert my influence for Walter—but Walter didn't have much influence'."

Actually Walter Dill Scott had misgivings

about accepting the presidency. The attractions of the position were

not unalloyed, for the University was in a critical condition. For

years there had been an annual deficit in the budget, which members of

the Board of Trustees had made up out of their own pockets. The physical

equipment of the University was sorely inadequate; the professional schools

in Chicago were housed in cramped, out-of-date quarters; living accommodations

for students in Evanston were limited and unsatisfactory. Faculty

salaries were too low, and the University therefore in danger of losing

its best men. All these and many other problems the new president

would be expected to solve.

For a long time Dr. Scott pondered the desirability

of accepting the leadership of an institution which faced a crisis.

When he did accept, it was with the stipulation that he be given an entire

year in which to study the University's situation and devise plans for

its future.

University presidents in America have always had to be extraordinarily versatile. In the 1850's the president of Northwestern had to be a scholar, a preacher, an administrator, a teacher, a disciplinarian, a counselor, something of an engineer and surveyor, a money raiser. In 1920 no fewer abilities were expected of him, and the greater magnitude of the institution increased his responsibility many fold.

He must be a practical man; yet he must

be an idealist. He must be scholarly enough to bring prestige to

his office; at the same time he must be a shrewd man of business.

He must accept complete responsibility before the public for the activities

of his faculty; at the same time he must protect the academic freedom which

a self-respecting faculty demands. He must be a diplomat with the

man to whom the laboratory

and library are inviolate, and with the

man to whom the advancement of business is the ultimate justification of

all things; with the alumnus who wants every "tradition" hermetically preserved,

and with the student who wants his education to be an advance copy of tomorrow's

newspaper. He must be able to inspire the giving of lavish endowments;

yet he must regard each dollar in the university budget as though it were

the last.

Chapter 4

Astute persons recognize that, had Walter

Dill Scott deliberately trained himself to assume the presidency of Northwestern

University in 1920, he could not have been better prepared than he was.

He would bring to high office the requisite academic prestige. A pioneer in the application of psychology to industrial problems, he had held, at Northwestern the first chair of applied psychology in the country. By a formal vote the psychologists of America had directed that his name should be starred in American Men of Science; in1918-1919 they had further honored him by electing him president of the American Psychological Association.

He would bring to his office a genius for organization and administration, brilliantly demonstrated in his victory over the iron traditionalism of the Army.

He would bring an invaluable understanding, rare in academic men, of business and business leaders, derived from his extensive study and experience in the field of psychotechnology. That such an insight would be indispensable to the university was only too obvious to those who pored over its budget.

He would bring a fresh interest in Northwestern on the part of its alumni—to whom the university now looked as never before for support—for he was the first of their number to be chosen for the presidency of their university. He was known, either as fellow-student or teacher, to is large a number of alumni as any other man—possibly to every person who had been enrolled on the Evanston Campus since 1891.

If any man could lead Northwestern through this critical period to a position of security and eminence Walter Dill Scott was that man.

In a recent public statement the president remarked that in the history of Northwestern University the period from 1851 to 1923 shows an emphasis on survival, the period since 1923 on "development". In his year of planning—1920-21—however, though that was still within what he designated as the struggle for survival, he planned strictly in terms of "development". Timidity was unknown to him. His aspirations for the university were ambitious, his plans big—but practical. As with Chicago's great city planner, Daniel Burnham, his motto might well have been, "Make no little plans—for they have no magic to stir men's blood."

How well he planned can best be measured by results—and in the eighteen years of his husbandry Northwestern University has known its greatest growth, both quantitative and qualitative.

Since President Scott assumed office, the

university has quadrupled ($1,400,000 to $5,230,000) the amount annually

expended for maintenance and instruction, and yet balanced its budget.

It has quadrupled ($11,960,000 to $47,600,000) the value of its plant.

It has quintupled ($5,625,000 to$26,700,000) its endowment.

In 1920 the School of Law, the Dental and Medical Schools, and the evening divisions were uncomfortably and unimpressively housed in two widely separated buildings in Chicago's loop. By 1926 they had been brought together in one of the finest metropolitan campuses in the country.

In 1920 the problem of housing women students was harassing not only the student body but their parents, the dean of women, and the community. Today the beautiful Women's Quadrangles are a showplace on the North Shore.

In 1920 the Evanston portion of the university library overflowed the dim crowded quarters of Orrington Lunt Library into odd corners of half a dozen other campus buildings. In 1932 the handsome Charles Deering Library was opened.

In 1921 the School of Journalism was established, in 1926 the School of Education, in 1934 the University College. Courses in adult education, which President Scott regards as one of the most important functions of a university so situated as Northwestern, last year provided classes for 13,492 students as against 2,598 in 1920.

President Scott's conviction that the duty

of an educator is not alone to serve students but to aid the community

and the nation as well has led Northwestern into great new fields of activity.

Most clearly demonstrated in the growth of the evening divisions, the increase

of the public service rendered by the university is represented also in

the establishment of such agencies as the famed Scientific Crime Detection

Laboratory, the Air Law Institute, the Traffic Safety Institute.

Concomitant with the development of first-rate facilities for !he Medical

and Dental Schools and the School of Law has been the growth of their public

clinics, which now serve 80,000 persons annually.

In 1920 Northwestern was regarded as primarily an Evanston institution—one with only local influence. The members of the Board of Trustees at that time were almost all Evanstonians, so limited were the relations of Northwestern with the city of Chicago. Today the Board numbers among its members some of Chicago's most prominent men. The Northwestern University Associates, comprised of influential men in the Chicago area interested in the university as a community institution, has been developed under his leadership. The organization of alumni into a national body conscious of itself as the university's principal public representative has been accomplished under President Scott's direction. Today the university holds a dominant position in the Middle West and has an international reputation, attested by the increasing number of students from foreign countries.

Although the full-time enrollment of the university has grown thirty percent since 1920, the growth has been regulated by a careful plan. Restrictive quotas have been established for most of the schools. More important, the selective process, limiting the enrollment to students of proved ability, was established early in Dr. Scott's administration. Whereas only sixty-five percent of the undergraduates represented the upper half of their high school classes in scholarship in 1920, today ninety percent of the undergraduates are upper-half students and more than sixty percent of this number are scholastically in the upper quarter of their graduating classes.

President Scott's special contribution to

psychology has borne fruit in the university. His studies of personnel

relationships have made him markedly sensitive to the need of the individual

for freedom, for personal responsibility and self-reliance, and for personal

expression. Thus while he has on the one hand a lively awareness

of the inevitable growth of the university population in our democracy,

he has concerned himself greatly with the preservation of the individuality

of the student within the large university community. In consequence,

he has encouraged the development of such agencies for individual development

and guidance as a tutorial system, by which students are provided additional

instruction in difficult subjects without cost, and a counseling system

through which they are aided in the solution of vexing financial, vocational,

religious, and social problems.

Key to the broad changes he has instituted for the benefit of the students has been his appreciation that there are 168 hours in the week, and that the fifteen or eighteen spent in the classroom form only a fragment of the time during which a university may contribute to the development of its students.

"The primary function of a college training, beyond that of imparting a certain amount of factual knowledge,",he asserts, "is that of producing changes in the behavior and thinking of students. Every hour of the week, within class and without, should contribute to this underlying purpose. We must break away from the traditional beliefs that the only place we can serve students is in the classroom; to that end progressive universities must increase their facilities to provide for the extra-curricular needs of individual students."

Despite the major part that has been his in all these developments, President Scott turns aside with a jest all attempts to credit him with the university's remarkable advance. At a dinner given in his honor by alumni in May, 1931, the warm applause and speeches of high praise elicited from him this typical response:

"Ten years ago next month you applauded when, for the first time, an alumnus was formally installed as your president. Your applause was an expression of great Faith.

"Five years ago I made a tour of our alumni clubs in America. Everywhere I was welcomed with generous enthusiasm. I realized that your applause was the expression of great Hope.

"At the end of the decade I stand before you and am quite overwhelmed with this unambiguous manifestation of your goodness of heart. I realize that your applause is an expression of great Charity.

"In rhetoric there is a figure of speech

known as a synecdoche which enables us to indicate a large concept by naming

a part for the whole . . . I well remember the very sentence that was used

in my old textbook to illustrate this figure of speech—‘Twenty sails entered

the harbor of Alexandria.' The word sails was intended to indicate not

only the canvas but also the hulls, the masts, the rigging, the cargoes,

and the crew . . . When statements are made that the President of Northwestern

University accomplished this, that, or the other, the statements are true,

but the speakers are making use of synecdoche. ln these statements the

term president indicates all the friends of Northwestern University."

This is not an expression of false modesty. His war-time associate, Dr. Frederick P. Keppel, now president of the Carnegie Corporation, replied to the President's self-deprecatory remarks that he was as free as humanly possible from "the Jehovah complex." ,

Close-linked with this modesty has been the caution with which he has avoided the pitfalls of publicity which beset the way of any public official. To those who would extol his successes he merely quotes three sentences: "If a man refers to his own honesty once it may be regarded as accidental. If he, refers to it three times he should be suspected. If his promoters emphasize his honesty you will assume that it cannot be taken for granted."

The President, however, has one achievement of which he is frankly proud: he has never been absent from his office for a single day because of illness.

It is not alone by mere daily presence at his office that the President manifests his vitality and health. He is a vigorous participant in outdoor games. It was not long ago that he engaged in a faculty ice-hockey game with such abandon that he finally skated off the pond with a broken nose.

Both he and Mrs. Scott are inveterate golfers, and rumors about the President's skill, which he denies, are numerous. The President's score is consistently in the 80's. According to one, he was recently trying his skill at driving, and on a 200-yard-hole at his club he drove five times to within six feet of the pin. According to another, a few days later, as the members of his foursome were preparing to drive over a long water hole, one of the party challenged him to drive two consecutive balls over the lake and into the fairway. He stepped to the tee and drove the two over—and then followed up immediately by lashing another pair onto the fairway.

As important from the student standpoint as a president's health, of course, is the freedom and ease with which he may be approached, and the lack of pretense with which he greets his visitors.

On many an American college campus the student who wants to confer with the president on matters of business has a difficult enough time obtaining permission to enter his sanctum sanctorum — and the one who hopes for nothing more than a few moments of genial conversation is often disappointed.

But this is scarcely true at Northwestern.

The door to the President's office is invariably open—and parents, students,

faculty members, trustees, and townspeople pass in and out in an unchecked

stream, And, as a matter of fact, so interested is President Scott in "his"

students that he not only receives them with undisguised pleasure when

they enter his office of their own volition but even encourages the practice

with special letters of invitation to new students.

"Walter Dill Scott," Dr. Frederick P. Keppel

once declared, "has always

succeeded in letting the other fellow do

his share of the work, and that is very difficult when the responsibility

is concentrated in one person."

Students, faculty, and administrators attest freely to the truth of his remark. The president's policy, when a problem or office lias been assigned to a member of the staff, has been to let that man alone—to give him full confidence and authority so long as his competence cannot be seriously questioned. The transfer of duties to his associates is complete; he does not take decisions out of the hands of those who have been made directly responsible for them. When a conflict arises as. for example between two departments, and he is approached as an arbiter, his practice is to compel the disputants, by his objective attitude and shrewd questioning, to air their differences completely and to find their own compromise. He believes this technique leads to more satisfactory solutions than any dictatorial procedure could.

By nature a conservative—in politics, religion, dress, and speech—he has quietly and successfully resisted all attempts to interfere with the rights of the faculty to express themselves in accordance with the dictates of their individual points of view, however liberal. An annual lecture series which has introduced to the campus such men as Clarence Darrow and Norman Thomas has brought to the President's desk hundreds of protests; yet no word of reproach or hint or restraint has reached the faculty member who directs the series. When another faculty member publicly expressed his belief that President Roosevelt's "court-packing plan" was constitutional, an avalanche of recrimination reached the President's office. The President, however, was firm in his opinion that this professor's legal judgment has as much right to expression as that of other legal experts. That the faculty is predominantly conservative is unquestionable; all the more reason, the president believes, for safeguarding the rights of those who find themselves temporarily not in accord with their associates.

His attitude toward the students is the same. When after a Peace Day demonstration an irate alumnus protested the presence of "pacifists and slackers" on the campus, Dr. Scott's retort was: "What of it? We have men on the campus in our Naval R.O.T.C. unit who are training for war."

Some years ago, during a nation-wide "red scare," the Baker bill, making compulsory the taking of a public oath of loyalty by teachers, was presented in the Illinois legislature. Northwestern had been far less afflicted by red-baiters than many another institution, but the President was one of the leading opponents of the bill.

"I am a Christian, but I do not believe

that Christianity would be advanced by persecuting the Jews. I am

a Republican but I do not believe that anything is to be gained by a denial

of freedom of the press to Democrats. I am a believer in capitalism,

but I do not believe that adherence to capitalism is reduced by experiments

in socialism. In religion, in politics, and in economics the truth

is not endangered by propaganda on the part of heretics . . . Error may

temporarily be kept alive by censorship, but truth is permanently strengthened

by freedom of speech."

The same spirit of broad impartiality was

manifest in Dr. Scott's attitude toward the merger of Northwestern and

the University of Chicago which was proposed several years ago.

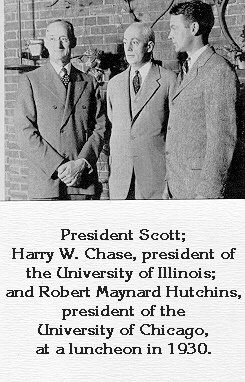

From a purely personal standpoint he would have stood to lose by such a merger for both he and President Hutchins had presented their resignations to the Presidents of their respective Boards of Trustees, to take effect upon the completion of the merger. But education, he felt, might have profited by the coalition and in consequence he brought his influence to bear in favor of a thorough and systematic investigation of the proposal.

Dr. Scott's keen desire to preserve Northwestern's own impartiality has been manifest several times in the caution with which he regards the proffer of gifts restricted by their donors to special uses.

Early in his tenure of office a prominent and wealthy citizen of Illinois proposed to the president the establishment at Northwestern of a school of military science, which was to be staffed with some of the famous generals of the World War. Dr. Scott listened to the proposal with interest, then replied: "We will accept your money to build at Northwestern University a great military school on one condition; namely that we be given an equal amount of money to establish a great school for peace." This ended the matter.

A sensible mingling of the traditional and the new has characterized Dr. Scott's educational theories; he has not cast away the old because it is old nor subscribed to, ill that is new because it is new.

"There are some who say that the old and the new in educational theory are as separate as transportation by foot and transportation by train—and counsel widespread acceptance of the new.

"But we must not forget that walking still

continues to be possible and belated foot-travelers continue to arrive—and

that there are many spots the pedestrian may reach that the train must

pass by."

Walter Dill Scott has been president of Northwestern University almost twice as long as any of his predecessors. He has led the university through a more marked transition than it has ever before known.

Yet his retirement will not mark the closing of an era. His lively way, his energy, have already projected him into the University's future.

In June of each year the president of Northwestern puts before the Board of Trustees the problems which he anticipates for the coming year or several ears. And in June of 1938 President Scott asked the Trustees to consider not alone the objectives of the next several years but those which should be laid down for 1951—the university's hundredth year—and the methods of attaining them.

The new emphasis will be reflected in the character and number of the teaching and research staff, in the character and number of the student body, and in the physical facilities with which both faculty and students will be provided.

Keyed to the speed of the aeroplane and radio and keenly attuned to the future in determining its policies, the new university, he recommends, should utilize all the creations of modern science.

"At the present time we are making practically no use of moving-pictures, radio, television, radio facsimile reproduction and the many other modern potential instruments of culture. Their extensive use during the next twenty-five years may result in a revolution in our methods of instruction."

As these plans, which his character and example have already influenced, are developed and fulfilled, he will no longer be president of the university—but he will still be Northwestern's Number One alumnus.

| HomePort Quick Finder | Back to Scott@HomePort | Search HomePort | Send e-mail to: HomePort |

| . |