Formal Logic

- Categorical logic (Aristotelian/Traditional logic) – a system of logic based on the relations of inclusion and exclusion among classes/categories

o Categorical claim – any standard-form categorical claim or any claim that means the same as some standard-form categorical claim

o Standard-form categorical claim – any claim that results from putting words or phrases that name classes in the blanks of either A-claims, E-claims, I-claims or O-claims.

-

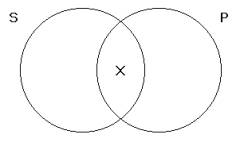

Venn Diagrams -

A-claim: All S are P.

E-claim: No S are P.

I-claim: Some S are P.

O-claim: Some S are not P.

o Affirmative claims – a claim that includes one class or part of one class within another; A- and I-claims.

o Negative claims – a claim that excludes one class or part of one class from another: E- and O-claims.

-

Translation into Standard Form

o Equivalent

claims – two claims are equivalent if and only if they would be true in all

and exactly the same circumstances

o “only”

– all claims of the sort “Only A’s are B’s” should be translated as “all B’s

are A’s.”

§

The word “only,” used by itself, introduces the predicate

term of an A-claim.

o “the

only” – all claims of the sort “The only A’s are B’s” should be translated

as “All A’s are B’s.”

§

The phrase “the only” introduces the subject

term of an A-claim.

o

Individuals – all claims of the sort “A is a B”

should be translated as “All people identical with A are B.”

§

Claims about single individuals should be treated as

A-claims or E-claims.

o Objects/Occasions/Places

– all claims of the sort “A is at or near B” should be translated as “All

objects/occasions/places identical with A are B.”

-

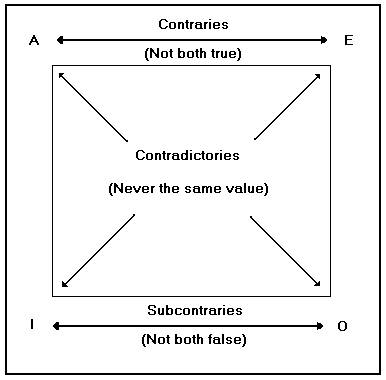

Square of Opposition -

- Converse

o Switch the position of the subject and the predicate

§ A - All A’s are B’s. → All B’s are A’s.

§ E* - No A’s are B’s. → No B’s are A’s.

§ I* – Some A’s are B’s. → Some B’s are A’s

§ O - Some A’s are not B’s. → Some B’s are not A’s.

·

All E- and I-claims, but not A- and O-claims, are

equivalent to their converses.

- Complementary terms – a term is complementary to another term if and only if it refer to everything that the first term does not refer to

o Often

accomplished by placing a “non” before the subject

- Obverse

1) Change the claim from affirmative to negative, or vice versa (i.e., go horizontally across the square)

2) Replace the predicate term with its complementary term

i. A - All A’s are B’s. → No A’s are non-B’s.

ii. E - No A’s are B’s. → All A’s are non-B’s.

iii. I - Some A’s are B’s. → Some A’s are not non-B’s (Some A’s are B’s.).

iv. O - Some A’s are not B’s. → Some A’s are non-B’s.

- Contrapositive

1) Switching the places of the subject and predicate terms, just as in conversion

2) Replacing both terms with complementary terms

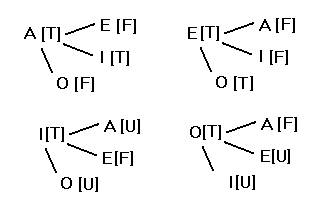

i.

A* - All A’s are B’s. → All non-B’s are

non-A’s. ![]() →

→ ![]()

ii.

E - No A’s are B’s. → No non-B’s are non-A’s. ![]() →

→ ![]()

iii.

I - Some A’s are B’s. → Some non-B’s are non-A’s. ![]() →

→ ![]()

iv.

O* - Some A’s are not B’s. → Some non-B’s are

not non-A’s (Some non-B’s are A’s.). ![]() →

→ ![]()

·

All A- and O-claims, but not E- and I-claims, are

equivalent to their contrapositives.

-

Number Area Process

o A-Claims

§ Place subject numbers in the Venn Diagram

§ Shade out the non-matching numbers in the subject term

· e.g., All A’s [1, 2] are B’s [2, 3]

o E-Claims

§ Place subject numbers in the Venn Diagram

§ Shade out the matching numbers in both terms

· e.g., No A’s [1, 2] are B’s [2, 3].

o I-Claims

§ Place subject numbers in the Venn Diagram

§ Place an “x” in the matching numbers or across borderline of matching numbers

· e.g., Some A’s [1, 2] are B’s [2, 3].

o O-Claims

§ Place subject numbers in the Venn Diagram

§ Place an “x” in non-matching numbers (in subject) or across borderline of non-matching numbers

· e.g., Some A’s [1, 2] are not B’s [2, 3].

- Equivalencies

-

Syllogisms

o 2

I-claims as premises create a false syllogism

o Rules

of syllogism validity:

§

Number of negative claims in premises must be the same

as the number of negative claims in the conclusion.

§

At least one premise must distribute the middle term.

§

Any term that is distributed in the conclusion of the

syllogism must be distributed in the premise.

o Distributed – a term that refers to every possible member of a class

§

A-claim – All A’s are B’s.

§

E-claim – No A’s are B’s.

§ I-claim – Some A’s are B’s.

§ O-claim – Some A’s are not B’s.

o Major term – predicate of the conclusion

o Minor term – subject of the conclusion

o Middle term – not in conclusion but in both premises

-

Truth Functional Rules

|

negation |

|

conjunction |

|

disjunction |

|

conditional |

||||||||

|

P |

~ |

P |

|

P |

& |

Q |

|

P |

v |

Q |

|

P |

→ |

Q |

|

T |

F |

T |

|

T |

T |

T |

|

T |

T |

T |

|

T |

T |

T |

|

T |

T |

F |

|

T |

F |

F |

|

T |

T |

F |

|

T |

F |

F |

|

F |

T |

T |

|

F |

F |

T |

|

F |

T |

T |

|

F |

T |

T |

|

F |

F |

F |

|

F |

F |

F |

|

F |

F |

F |

|

F |

T |

F |

|

|

|

Only true if both terms

are true |

|

One true part makes all

true |

|

Only false if antecedent

is true & consequent false |

||||||||

Informal Logic

-

Claim – a statement that is either true or false

-

Issue – primary topic of conversation/discussion

o Argument

– a set of claims with a conclusion supported by premises

- Defining Terms.

o Stipulative Definitions – to introduce unusual or unfamiliar words, to coin new words, or to introduce a new meaning to a familiar word.

o Explanatory Definitions – to explain, illustrate, or disclose important aspects of difficult concepts.

o Precising Definitions – to reduce vagueness and eliminate ambiguity.

o Persuasive Definitions – to influence the attitudes of the reader

- Emotive Force – the emotional baggage attached to particular words.

- Ambiguities

o Semantical Ambiguity – an ambiguous claim whose ambiguity is due to the ambiguity of a word or phrase in the claim.

§ Grouping Ambiguity – a kind of semantical ambiguity in which it is unclear whether a claim refers to a group of things taken individually or collectively.

o Syntactical Ambiguity – an ambiguous claim whose ambiguity is due to the structure of the claim.

- Fallacies

o Fallacy of Composition – to think that what holds true to a group of things taken individually necessarily holds true of the same things taken collectively.

o Fallacy of Division – to think that what holds true of a group of things taken collectively necessarily holds true of the same things taken individually.

- Logical Force – the relationship between two or more phrases where they have the power to “force” the conclusion.

- Nonargumentative Persuasion/Slanters

o Euphemism – an agreeable or inoffensive expression that is substituted for an expression that may offend the hearer or suggest something unpleasant.

o Dysphemism – a word or phrase used to produce a negative effect on a reader’s or listener’s attitude about something or to tone down the positive associations the thing may have.

o Persuasive Comparison – a comparison used to express or influence attitudes or affect behavior.

o Persuasive Definitions – a definition used to convey or evoke an attitude about the defined term and its denotation.

o Persuasive Explanations – an explanation that tells us how or why something happens in terms of the physical background of the event.

o Stereotype – an oversimplified generalization about the members of a class

o Innuendo – an insinuation of something deprecatory.

o Loaded Question – a question that rests on one or more unwarranted or unjustified assumptions.

o Weasler

– an expression used to protect a claim from criticism by weakening it.

§ May want to bring attention to a claim but hold open a way out if the claim is challenged.

o Downplayers

– an expression used to play down or diminish the importance of a claim.

§ Wants to call attention away from a claim in the first place by “downplaying” its significance.

o Hyperbole

– an extravagant overstatement.

o Proof

Surrogate – an expression used to suggest that there is evidence or

authority for a claim without actually saying that there is.

-

Pseudoreasoning I

o Smokescreen/Red

Herring: bringing up an irrelevant topic to draw attention away from the

issue at hand.

o Subjectivist

Fallacy: asserting that a claim may be true for one person but not for

another.

o Appeal

to Belief: urging acceptance of a claim simply because some selection of

other people believe it (when those believers have no more knowledge or

expertise in the subject than you do).

o Common

Practice: justifying an action or practice on the grounds that lots of

people (or a significant number within a certain category) engage in it.

o Peer

Pressure: accepting a claim because we believe it will gain us approval

from our friends or associates, where that approval is irrelevant to the truth

of the claim.

o Bandwagon:

supporting a position, candidate, or policy simply because we think it is going

to win or become the dominant alternative.

o Wishful

Thinking: believing that a claim is more likely to be true than just on the

basis of our desire that it be true.

o Scare

Tactics: accepting or urging acceptance of a claim on grounds of fear, when

the thread is not relevant to the issue addressed by the claim.

o Appeal

to Pity: accepting or urging acceptance of a claim on grounds of pity, when

the appeal is not relevant to the issue addressed by the claim.

o Apple

Polishing: accepting or urging acceptance of a claim on grounds of vanity,

allowing praise for oneself to substitute for judgment about the truth of a

claim.

o Horse

Laugh/Ridicule/Sarcasm: making someone the butt of a joke or humorous

remark in an effort to get him or her to accept a claim, or accepting a claim

simply to keep from being the butt of such remarks.

o Appeal

to Anger or Indignation: substituting anger or indignation for reason and

judgment when taking a side on an issue.

o Two

Wrongs Make a Right: deciding to do X to somebody because you believe they

would do X to you given the chance, or justifying an action against someone as

“making up” for something bad that happened to you. This may not apply when you

retaliate directly against the person who first harmed you.

-

Pseudoreasoning II

o Ad

Hominem: attacking the person offering a claim or argument rather than

attacking the claim or argument.

§

Personal Attack: saying bad things about the

individual’s character, history, and so forth.

§

Circumstantial Ad Hominem: basing the attack on

the individual’s situation, job, or other special circumstances.

§

Pseudorefutation: basing the attack on the claim

that the individual has spoken or otherwise acts as if he or she doesn’t

believe the claim; a charge of inconsistency.

§

Poisoning the Well: committing an ad hominem

before the individual even has a chance to make the claim in question; an “ad

hominem in advance”.

o Genetic

Fallacy: denying a claim because of its origins in some group, political

party, or other organization; different from ad hominem in that it is not an

individual under attack.

o Burden

of Proof: requiring the wrong side of an issue to make its case.

o Straw

Man: offering or accepting a distorted or exaggerated version of a

proposition in place of the actual, more reasonable version.

o False

Dilemma: erroneously narrowing down the range of alternatives, saying we

have to do X or Y when in reality we might choose Z.

§

Perfectionist Fallacy: allowing only

alternatives of adopting a policy that will solve a problem perfectly and

completely or doing nothing at all.

§

Line-Drawing Fallacy: requiring that a precise

line be drawn someplace on a scale or continuum when no such precise line can

be drawn; usually occurs when a vague concept is treated like a precise one.

o Slippery Slope: refusing to take the first step in a progression on unwarranted grounds that doing so will make taking the remaining steps inevitable; or insisting erroneously on taking the remainder of the steps simply because the first one was taken.

o Begging the Question: assuming as true the very claim that is at issue.

-

Arguments and Explanations

o Arguments

– try to show that something is, or will be, or should be the case.

§

Justification is always an argument.

o Explanations

– try to show how or why something is or will be.

o Difficulties

in Differentiating Arguments from Explanations

§

People often are not clear on whether they are arguing

something or explaining something.

§

The same words and phrases are used in presenting

arguments and in offering explanations.

§

The word “explanation” and its derivatives are

themselves used in arguments.

§

Explanations are often used in arguments and are

sometimes used as arguments.

-

Explanations

o Physical

Explanations – an explanation that tells us how or why something happens in

terms of the physical background of the event.

§

3 Mistakes to Avoid

·

Creating an endless causal chain to explain an event

·

To expect a reason or motive behind the chain of events

·

Give the wrong “technical” level for the audience

(using complicated terminology, phrasing, etc.)

o Behavioral

Explanations – an explanation that attempts to clarify the causes of

behavior in terms of psychology, political science, sociology, history,

economics, and other behavioral and social sciences. Also included are

explanations of behavior in terms of “common sense psychology,” that is, in

terms of someone’s reasons and motives.

o Functional

Explanations – an explanation of an object or occurrence in terms of its

function or purpose.

§

Phrases can be restated using “purpose” or “function”

without changing the meaning of the original sentence.

-

Spotting Weak Arguments

o Testability

– can the argument be subject to testing (are there well established methods to

put the argument to a test)?

o Noncircularity

– is the phenomenon the only evidence for the argument (simply

restating the argument as evidence)?

o Relevance

– does the explanation have a connection with the thing or event being

explained (or, does the explanation create any degree of predictability)?

o Freedom

from Excessive Vagueness – does the argument rest on vague premises or

ideas (are the ideas used to argue your point clear in their meaning)?

o Reliability

– does the explanation prove useful in predicting the phenomenon/idea

expressed (does your argument survive multiple tests)?

o Explanatory

Power – how much does the argument explain (does it leave anything

unresolved that is relevant to the issue)?

o Freedom

from Unnecessary Assumptions – does the argument require more assumptions

than an alternate argument (which argument uses the less unsolved/unresolved

ideas)?

o Consistency

with Well-Established Theory – does the argument follow well

established/founded theories on reality (does it fit with the “facts” already

known or does it differ with serious qualifications)?

o Absence

of Alternative Explanations – is there an alternate argument that could

explain the evidence equally or better than your argument (is your argument the

most viable explanation or do others provide a good or better substitute)?