"An animal's eyes have the power

to speak a great language."

-Martin Buber

|

|

A TALE OF TWO LARRYS | state ['stat] noun 1: mode or condition of being; 2: condition of mind; 3: social position, esp high rank; 4: a body of people occupying a definite territory and politically organized under one government, also the government of such a body of people; 5: one of the constituent units of a nation having a federal government; verb: to express in words.

Larry Watson received The Milkweed National Fiction Prize and The Mountains and Plains Bookseller Association Regional Book Award for Montana 1948. It's also earned him comparisons to Harper Lee. The novel recounts a series of horrendous crimes against Native American girls that ultimately result in murder. It's a dark tale played out against the backdrop of Bentrock, an idyllic small town tucked away in the northeast corner of Montana. The narration is presented through the memory of David Hayden - the son of the sheriff - a boy of only twelve when the crimes of this story come to light. The perpetrator, his uncle.

Character

Plot

Conflict

The subject matter of Montana, and its narration, begs comparison to Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird (HarperCollins, $16.99). Like Mockingbird, it exposes unsavory racial attitudes lying just beneath the surface of otherwise upstanding members of society. Also, like Lee's masterpiece, it relies on the narration of a child - or more precisely, childhood memories - to expose these attitudes. While reminiscent of Mockingbird, Watson's writing is more akin to that of Lee's childhood friend, Truman Capote. In both style and tempo, I'm reminded of his short story collection, A Christmas Memory, One Christmas, & The Thanksgiving Visitor (Random House, $13.95). One more comparison: Also like Mockingbird, Montana 1948 has a long shelf-life ahead of it.

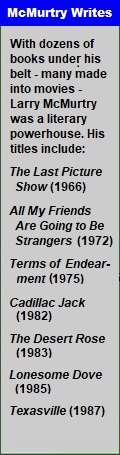

Texasville is the follow-up to Larry McMurtry's highly acclaimed novel The Last Picture Show (Dell, .75). Set in Thalia, Texas, he's brought the gang back in a sequel full of tilts and surprises. The Last Picture Show was generally depressing in its portrayal of a 1950's west Texas community that felt closer to a ghost town, youthful expectation its most redeeming quality. Texasville has none of that. Whereas Picture Show was a story written in sepia, Texasville is written in Technicolor.

The story swirls around the life of Duane Moore, who played Homecoming King to Jacy Farrow's Queen (portrayed by Jeff Bridges and Cybill Shepherd, respectively, in 1971's film version of Picture Show). Thalia has seen enormous prosperity, followed by an even bigger bust, which everybody has their fingers in one way or another. Duane is holding on by a thread, but that doesn't seem to affect his wife's spending habits. Virtually everyone in town is in

the same boat, but save for a few dour faces, they're nonplussed by it. Theirs is a uniquely Texan approach to adversity.

Thalia is the county seat of Hardtop County. McMurtry's telling coincides with the county's centennial - a mad celebration that dovetails well with the craven lives of Thalia's inhabitants. The oil glut - and the economic recession unleashed by it - causes McMurtry's characters to behave irrationally, a trait brought to the forefront by the centennial celebration. Yet, as a whole, they're mostly upbeat. Despite rampant extra-marital affairs, divorce threats, unplanned pregnancies and predatory bankers circling like vultures, the characters of Texasville remain non-circumspect. Sure, Duane gets down in the dumps, but it's handled with the adroit fashion of a master that makes us sympathetic, while holding our interest.

McMurtry walks a fine line. Already loved for his portrayals of the American west, Texasville only adds to that acclaim. He inserts so much humor into the story though, it verges on lampoon. Not that his characters shouldn't be laughed at; but they shouldn't be mocked. No fool, he stops just shy of that, delivering a heartfelt sequel that stands shoulder-to-shoulder with its predecessor.

And yes, Jacy's back.

posted 11/21/22

TOP |