Added 8-3-17

Updated 22-4-21

For more than a century ballisticians have sought the ideal military rifle round.

The definition of “ideal” has, however, changed over this period of time.

In the latter half of the Victorian-era, massed rifle fire was being used to engage enemy formations at ranges of 2,000 yards.

By the Second World War it was more common to be firing against individuals who were crawling or sprinting between cover.

For most purposes, the long-ranged Victorian-vintage military rounds were overpowered.

If rifle ammunition was designed for the more likely occurrence of targets at less than 500 metres, a number of advantages might be gained.

Rifles might be made lighter and shorter.

Ammunition would be lighter and use less powder.

Recoil would be reduced, simplifying training and permitting more rapid follow-up shots.

A lower impulse round would facilitate the use of selective fire and semi-automatic actions.

The philosophy behind “intermediate” rifle rounds has been covered in many other sources so I will not go into great detail here. The reader who wishes to know more is encouraged to read the Defensive Rifle chapter of my book, “Survival Weapons: Optimizing Your Arsenal”.

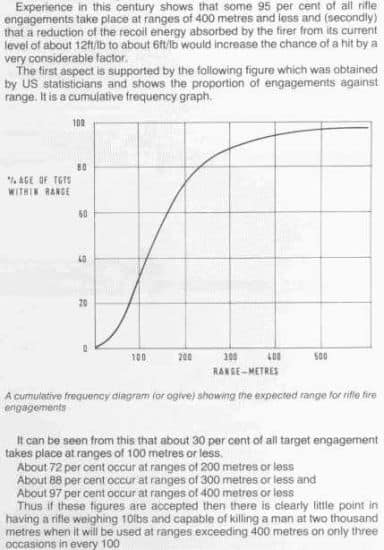

Below is a cumulative frequency graph that was published in the 1976 edition of Jane’s Infantry Weapons. Note that only 3% of shots are at greater than 400 metres and 72% at 200 metres or less.

Operations in Afghanistan produced demands for weapons and ammunition with greater range. Some of these complaints may be due to lightweight 5.56mm rounds being particularly prone to cross winds. Some of this desire may be psychological. With times of flight of a second or greater, a moving target needs to be very predictable to be hit by a single shot.

Several alternates to the 5.56x45mm round have been proposed. A common feature to all is the choice of a high sectional density round of between 6mm and 7mm calibre. A high sectional density means the round loses less velocity in flight. This results in shorter flight times, flatter trajectories, less deflection and better terminal penetration. The 6.5mm Grendel and 6.8mm SPC have gained some attention as 5.56mm alternatives. Neither can be used in standard M16/M4 magazines. The SPC needs the magazine to be modified while the Grendel uses its own dedicated magazine that fits in an M16 well. Converting a 5.56mm rifle to either round requires new bolt faces and other components in addition to a new barrel. Neither round is compatible with belt-feed mechanisms such as the M249. The Scrapboard’s proposal was to create a round with a 6.5mm or 6.86mm high sectional density bullet mounted in a 5.56x45mm case. This concept was featured in “#27 Special Weapons for Military & Police, 2004 p.62”. A few years later this configuration became available as the 6.5mm MPC. Converting weapons in current service to the 6.5mm MPC round would only require a replacement barrel. The round can be used in the thousands of magazines already in use, without modification. It is also compatible with M249 belt-feed. The 6.5mm MPC is a good illustration of how terminal velocity is more important than muzzle velocity. The superior sectional density of the round means that a 6.5mm MPC fired at a relatively modest 2,400 fps will still be supersonic at 900 yards.

Ballistically, the 6.5mm MPC is superior to the 5.56mm but not the equal of the 6.5mm Grendel. It may not be the ideal rifle round, but it is the best option for improving the thousands of 5.56mm weapons in current service. Potentially weapons in active areas could be upgraded while those in CONUS and/or used for training could be left in 5.56mm.

While not optimal, the intermediate round most likely to see wider use is the .300 AAC Blackout, effectively a SAAMI-fied .30 Whisper. Like the 6.5mm MPC it is based on a .221/.223 case so compatible with unmodified STANAG magazines and M249 belt-feed. Its subsonic performance makes it a logical choice for special forces, covert and special-purpose units. It could be argued, however, that this role is better filled by 7.62x39mm weapons provided with subsonic loads such as the Russian 194-195gr 57-BZ231U. This would allow units to utilize enemy ammunition.

There is, however, an inherent problem with seeking the ideal military rifle round. It is not what we need!

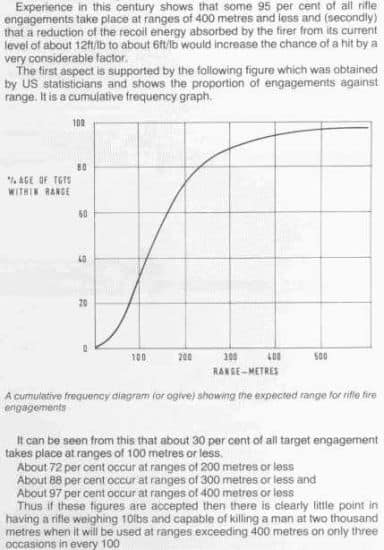

Below is another cumulative frequency graph from the same source as the one above. It can be seen that 50% of machine gun engagements take place at more than 750 metres.

Jane's Infantry Weapons, 1975 page [21] comments: “It must be noted that the curve has been considerably influenced by the large amount of machine gun fire used in the past on fixed-line firing, to harass the enemy and to deny ground. This machine gun task has been carried out at long ranges in the past and the present view is that if a machine gun carries out this task at all it should be a gun held at Company or Battalion level. ”

Similarly, we do not know if this data included the use of heavy machine guns or vehicle- and helicopter-mounted weapons. The ranges at which a squad level machine gun is used is likely to be lower. SLA Marshall’s study of infantry weapon use in the Korean War notes that machine guns were typically used at 400 yards or less, and rifles at 200 yards or less.

Squad-level machine guns in current use either use the 5.56x45mm round or the 7.62x51mm NATO round.

The long-range shortcomings of the 5.56mm round have been discussed elsewhere on the Scrapboard.

The standard loading of 7.62mm NATO was designed as a rifle round. The choice of a 147-150gr bullet was intended to give a high muzzle-velocity and flat medium-range trajectory rather than a performance suited to longer ranges from machine guns.

The 7.62x51mm NATO round inherited this feature from the .30-06, which was noted as being a poorer long range medium MG round than of its contemporaries.

The ideal military rifle cartridge is not the ideal military round!

The ideal military round would be a machine gun round that was still compatible with realistic rifle use.

Such a round would be capable of replacing both the 5.56x45mm and the 7.62x51mm rounds.

In the machine gun role, such a round should at least equal the 7.62x51mm. It should have sufficient power and range for use in vehicle- and helicopter-mounted weapons.

In the rifle role it should have less recoil and be easier to shoot than the 7.62x51mm, and should perform better than the 5.56x45mm.

In the rifle role it should be capable of accurate semi-automatic fire and rapid follow-up shots against targets out to at least 500 metres. Fully-automatic rifle fire should have a practical level of accuracy against targets within 20-50 metres range.

Anthony G. Williams gives an interesting summary of the design criteria that such a “next generation” round may need to meet.

The most logical approach to performing better than both the 5.56mm and 7.62mm is to use a more efficient bullet design. For a standard-sized, short-action compatible cartridge that means a bullet of between 6 and 7 mm to give a higher sectional density. Williams does not bother to speculate as to whether this “next generation round” will be conventional, caseless, polymer-cased or some other configuration. There is, perhaps, an implication that the round will be smaller than a 7.62x51mm and bigger than a 5.56x45mm. If it is conventional, would it perhaps be something like a 6.5mm version of the .280 British?

The .280 British used a 43mm case and had an overall length of 65mm. Is a 65mm overall length a significant difference over the 70mm of a 7.62x51mm round? Both rounds were based on the 12mm diameter .30-06 case. A wide variety of weapons designed for the 7.62x51mm are available. It is logical to base the next generation on the .30-06 case and give it the same overall length as the 7.62x51mm. The longer case length will better accommodate the long, non-plumbic bullets that future military ammunition is likely to use.

A number of other calibre rounds are based on the case of the 7.62x51mm, aka .308 Win. There is the .243 Win and the 7mm-08 Rem. Given the ballistic advantages of the 6.5mm calibre it would be surprising if there had not been attempts to combine this case and bullet. Such a round is the .260 Remington, aka 6.5-08 A-Square or 6.5x52mm. Many tactical shooters have become interested in this round after its successes in long-range sniping competitions. The 6.5 Creedmoor (6.5x49mm) is a modification of the .260 Rem designed to be more compatible with AR-10B magazines when loaded with long bullets. The new military round discussed here is likely to be closely based on one or both of these cartridges. For convenience, and to distinguish it from the numerous other 6.5mm rounds in use, we will call this round the “6.6mm GPC”.

This article notes that the .260 Rem “duplicates or beats the .300 Winchester Magnum’s trajectory with less recoil than .308.” and that:

“Compared to the venerable .300 Winchester Magnum’s most common load - a 190-grain Sierra MatchKing at 2900 fps - the .260 has about 17% less wind drift and a few clicks less drop. Even though it shoots a 140-grain bullet, it still has 87% of the Magnum’s energy at 1000 yards because its slim design yields a much higher ballistic coefficient (BC) value, so it retrains velocity longer. It also has 60% less recoil than the 300.

The .260 Remington blows .308 out of the water. It has 35% less wind drift and about 10 MOA less drop at 1000 yards than the standard 175-grain M118LR load. Despite a 35-grain deficiency in bullet mass, it has 31% more energy because it loses less along the way due to atmospheric drag, hitting 350 fps faster at 1000 yards.”

The performance of the .260 Rem/6.5 Creedmoor in sniping competitions indicates that a 6.6mm GPC round based on them would be more than adequate as a machine gun round. It is also likely to have sufficient accuracy for the designated marksman role or as an alternative to the .338 for snipers. As a hunting round, the .260 has been used to take animals as large as caribou, wild boar and black bear, so has sufficient terminal effects for combat use. High sectional density and energy retention will facilitate penetration of body armour and cover. A 140gr 6.5mm bullet has a sectional density of 0.296 compared to the 0.226 of a 150gr 7.62mm and the 0.177 of a 62gr 5.56mm.

Making the replacement for the 5.56x45mm and 7.62x51mm the same length as the latter round has little effect on the end users. Many soldiers are used to handling the 7.62x51mm already. Using the same cartridge case and length actually simplifies conversion and manufacture.

One possible objection to the above proposal is that the diameter of the rounds reduces magazine capacity compared to the 5.56mm. There are not that many cartridge cases in common use that are intermediate between the 9.6mm diameter of the 5.56mm case and the 12mm diameter of the 7.62x51mm. The 6.5mm Grendel round uses the 11.35mm case of the 7.62x39mm round and it seems unlikely this would offer a significant increase in magazine capacity over a 12mm case. The 6.8mm SPC uses the 10.7mm .30 Rem case that is also used for the 10mm Auto pistol round. The 5.45x39mm case is 10mm diameter. Judging by the ballistics of the .25 Rem, using a .30 Rem case for the 6.6mm GPC would significantly reduce performance. Granted, information for the .25 Rem is somewhat dated and some improvement may be seen with modern powders and heavier/more modern bullets. The most prudent option seems to be to use a round based on the .308/.30-06 case.

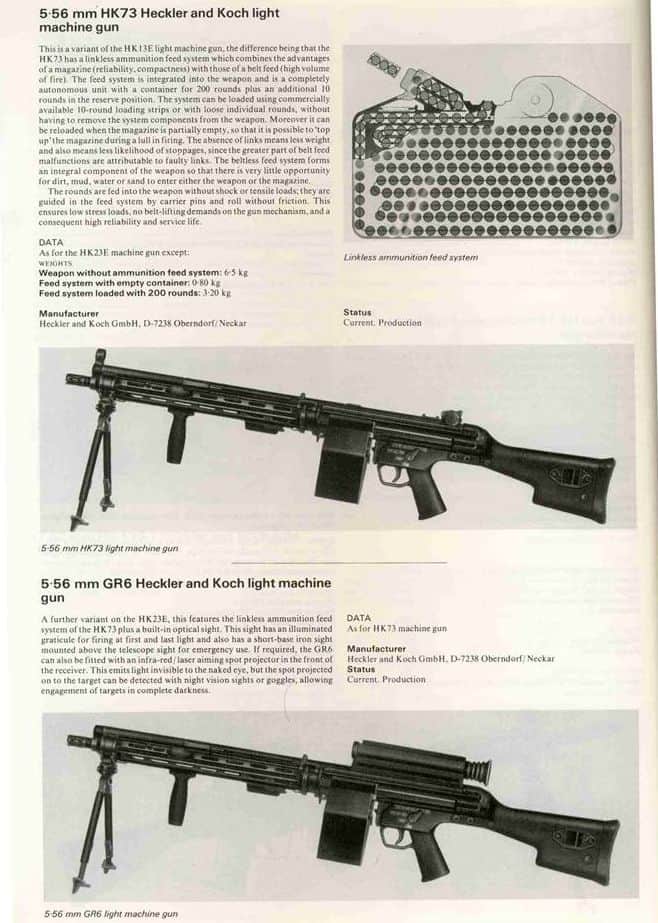

Converting existing 7.62x51mm machine guns to 6.6mm GPC will be relatively simple. A new barrel would be fitted and any necessary adjustments made to the gas system. Weapons such as the MG42/MG3 that use roller-delayed blowback may need some additional components replaced. Hecker and Koch once demonstrated the “HK73” squad machine gun with a linkless feed system. This could be replenished with stripper-clips without being removed from the weapon, possibly while still firing. This would be an attractive feature on the next generation 6.6mm GPC MGs.

The 6.6mm combat rifle (or “battle-carbine”) will probably be something like the SR-25 or AR-10B with a 16" barrel. See this article and this interview on the performance of the 6.5mm Creedmoor in 16.5" barrels.

Such weapons have an unloaded weight similar to that of an M16/M4 and slightly less than that of an AK-47/AKM.

Existing weapons could be converted by replacing the barrel and calibrating, modifying or replacing the gas system if necessary.

Bolt faces and magazines are already compatible.

Operation of an SR-25 or AR-10B will be familiar to soldiers already trained with AR-15 weapons.

The 6.6mm GPC round would also be compatible with the SCAR-H. Kits to convert the SCAR-H to .260 Rem for use with SR-25 magazines are already available.

A 27-round magazine with a capacity for 30 rounds should be developed for the SR-25/AR-10B/SCAR-H. This might take the form of a four-column Suomi “coffin” magazine. 50-round drums and 100-round C-mags designed for 7.62x51mm rifles are already available. These drums will also accommodate 6.5mm Creedmoor ammunition and probably .260 Rem too.

Magazines, and preferably weapons, should be compatible with stripper-clip loading. Ammo would be issued in nine-round strippers, allowing a 27 round magazine to be topped up after only six rounds have been expended.

The recoil from a .260 Rem/6.5mm Creedmoor is significantly less than that of the 7.62x51mm. A 7.5lb .260 Rem/6.5mm Creedmoor firing a 140gr with 43.5gr powder at 2,750 fps produces 15.35 ft/lbs of recoil at 11.48 fps for a recoil impulse of 2.68 lbf.s. The same weight 7.62mm/.308 firing a 150gr with 43gr powder at 2,800 fps produces 17.05 ft/lbs at 12.1 fps for a recoil impulse of 2.82 lbf.s. A rifle/battle-carbine using 6.6mm GPC would be easier to use for rapid semi-automatic or close-range fully-automatic fire than a 7.62mm NATO weapon.

The cartridge itself may need some changes to adapt it to military service. The propellant powder used needs to be of a formulation that does not produce much muzzle flash, even when used from weapons with 16" barrels.

Non-lead ammunition is becoming standard for military use so the bullet selected for the 6.6mm GPC should be of this form. Concerns about body armour suggest that in the future there is unlikely to be a distinction between “ball” and “armoured piercing” (AP) rounds for active service. A tracer variant will be needed. There may be a requirement for an AP-I variant along the lines of the Russian B-32/7B73 with a base incendiary chamber. A lower cost ball round for training may be prudent.

An interesting possibility, inspired by comments in this article is that two loadings of the 6.6mm GPC be developed. The “standard” load would probably be a 135-140gr streamlined round. This would be a high penetration round that can engage targets at ranges of more than 1,000 m when used in machine guns or precision weapons. The “urban” load would be for police or low-intensity operations. The urban load is loaded with a 100-120gr (SD: 0.211-0.254) non-streamlined bullet that is fired at high velocity for a flatter, medium-range trajectory with a reduced chance of overpenetration. Streamlining or boat-tailing only affects the subsonic portion of a bullet’s flight. Streamlining is redundant for rounds that are to be mainly used at supersonic ranges. The urban load has the potential to be a useful intermediate round. A subsonic loading of 155gr+ may be developed for special applications.

The proposed 6.6mm GPC uses mature, proven technologies and could be brought into service in just a few months. It would simplify platoon logistics while greatly increasing unit and individual capability.

USSOCOM compared the 7.62x51mm, .260 Rem and 6.5mm Creedmoor in the sniper role:

“SOCOM determined that 6.5 Creedmoor performed the best, doubling hit probability at 1,000 m (1,094 yd), increasing effective range by nearly half, reducing wind drift by a third and having less recoil than 7.62×51mm NATO rounds. Tests showed the .260 Remington and 6.5mm Creedmoor cartridges were similarly accurate and reliable and the external ballistic behaviour was also very similar. The prevailing attitude is that there was more room with the 6.5mm Creedmoor to further develop projectiles and loads.”

The potential of this round for weapons other than sniping rifles still remains unrealized in many circles!

USSOCOM Adopts 6.5 CreedmoorBy the Author of the Scrapboard : | |

|---|---|

| Attack, Avoid, Survive: Essential Principles of Self Defence Available in Handy A5 and US Trade Formats. |

| |

| Crash Combat Fourth Edition Epub edition Fourth Edition. |

| |

| |