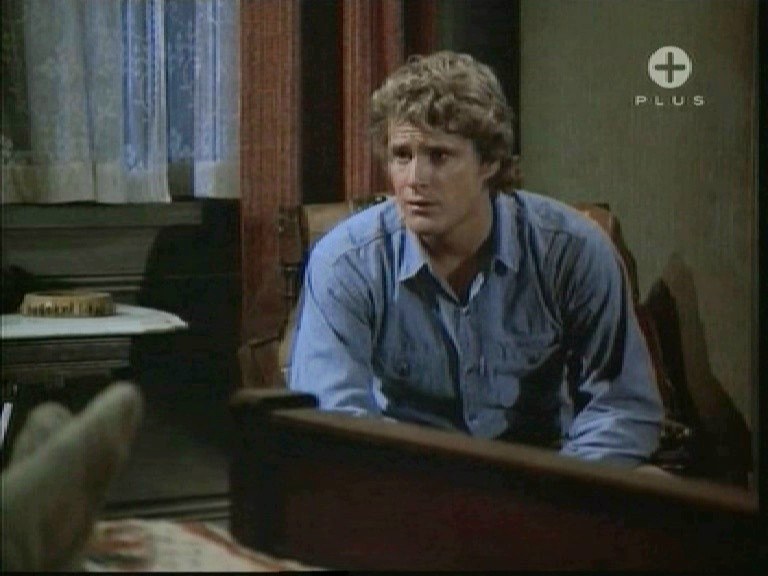

The Kid chose not to dignify that question with an answer. Instead, he turned his attention to the thick splatters of rain now kicking up small clouds of dust on the windowsill. Heyes watched him for a moment before suggesting, “Why don’t you close the window before it starts to rain hard?”

“Because the room stinks,” Curry snapped. “It smells like something curled up and died in that mattress. This room stinks, this hotel stinks, this whole town stinks.” He poked at the coins in his hand. “Being broke stinks.”

It was no use arguing; the Kid was right. Heyes resumed reading and shifted his weight against the lumpy mattress upon which he was sprawled. After a moment, he lowered his newspaper again. “Kid, I think I know what’s eating you.”

“Not eating—that’s what’s eating me. We haven’t had a decent meal in two days. Nothing but stale biscuits and jerky.”

That was true, too. “Today’s the 15th.”

“So?”

“April 15.”

“So?”

“April 15, 1889—so it was three years ago tonight that we were in Lom’s office and he was telling us all we had to do was stay out of trouble. . . .”

“For one year.” Curry threw his handful of coins onto the floor in disgust. “One year, and it’s been three. Every time Lom asks him about us, he finds some excuse to put us off.”

“Yeah.”

In the silence that fell between them, they could hear distant thunder and a commotion from the street below as travelers rushed for shelter before the storm hit. The Kid was right: the hotel stank, the town stank, the whole rotten deal stank.

Curry stared at the bank across the street. Probably, the bank’s security system stank too.

The mattress springs squealed as Heyes sat bolt upright. “Kid, I’m just as tired of waiting as you are, and just as mad. Besides, as many governors as this territory has had in the last four years, if somebody doesn’t grant that amnesty soon, we’re going to be forgotten about.”

Curry grunted as he dropped into a chair. “Yeah. Who’s governor this week?”

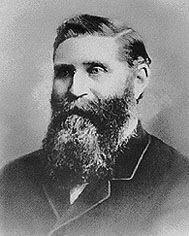

Heyes flipped the newspaper back to the front page and scanned a headline for the answer. “Hmph. Warren just got reappointed last week.”

“Again.” Kid shook his head in irritation. “Can’t these politicians just stay put? How many governors has it been, Heyes? How many deals with how many governors?”

Heyes counted on his fingers. “Warren, Baxter, Morgan—no, wait, we didn’t have a deal with him; he only lasted a month. Warren, Baxter, Morgan, Moonlight, now Warren again.”

“Guess we better go see Lom tomorrow, find out if the deal’s back on.”

Heyes flung the newspaper away. “I’ve had enough, Kid. If the governor’s going to welch on his deal with us, then we might as well welch on our deal with him.”

“Right.” The Kid reached for his gunbelt. “Just what I was thinking. It’ll be dark in another hour. There’s a bank across the street just waiting for us to come and help ourselves.”

“Help ourselves. . . . By golly, Kid, you’re right. That’s what we should do: help ourselves. All this secrecy, that’s the problem. The governor can welch on us because only Lom and us know about it. But if the rest of Wyoming knew. . . .”

Curry waited as his partner’s eyes glazed over with a scheme. He almost forgot his hunger—almost—in wondering what drama was playing out in Heyes’ imagination.

A few minutes later, Heyes began to pace. The Kid smiled: this was a good sign. Next would come the Socratic questions as Heyes worked on his plan aloud. “Kid, what’s the difference between us and any other outlaw working today?”

“Apart from the fact that we’re retired?”

“Apart from that.”

“About $15,000.”

“Right. And why is that? Why’s the reward on us so much higher?”

“Excellence. We’re a bit better at what we do—at what we did.”

“Well, that’s true, but what I’m getting at is: publicity.”

“Excuse me?”

“Publicity. Public relations. It’s not just our skill and our brains that make us successful—though in all modesty I must admit we’ve got plenty of those. It’s the way the public feels about us.”

“Huh?”

“Why, they love us, Kid, they just love us. We steal from the banks and railroads that have been stealing from them. We balance the scales, so to speak. And we do it without hurting anyone.”

“What’s this got to do with amnesty, Heyes?”

“It may just be our ace in the hole, Kid.” Heyes tucked his shirt into his pants and grabbed his hat. “Come on. Pick up those coins. We’re going to need them to send telegraphs.”

**************************************************

The governor’s personal secretary rapped lightly before opening the office door. “Sir, Sheriff Lom Trevors and friends to see you. They say they have an appointment.”

“They do. You can go home for the night, Elvin. I won’t need you.” Warren stood, nervously straightened a few papers on his desk, then gulped the last of a cold cup of coffee. “All right. Show them in.” Warren glanced at Lom, quickly lost interest in him, and instead stared hard at Lom’s companions, two elderly gentlemen in dress suits.

When the secretary was safely out of earshot, Lom closed the door behind them and the elderly men stepped toward the governor’s large mahogany desk. They moved surprisingly quickly for their apparent age.

“Governor,” Lom nodded a greeting.

“Are you--“ Warren blanched, but stopped himself before the unmentionable names leaked out.

“Yes, sir.” The brown-suited man shifted his walking cane from his right hand to his left so that he could offer a handshake. “Hannibal Heyes.”

The gray-suited man came forward next. When his thick eyeglasses slid down his nose, he pulled them off and pocketed them. “Jed Curry, sir.”

“Well.” The governor cleared his throat and sat down hard on his cushioned swivel chair. “Be seated, please.”

Once they were settled, Lom began, “Three years ago, sir, we negotiated a verbal contract with you. We’ve fulfilled our end of the deal—three times over. Now it’s your turn.”

“Gentlemen, as much as I—“

“No.” Curry leaned forward, his blue eyes icy.

Warren tried again. “I wish I could—“

“No,” Curry interrupted again.

“We had a deal, Governor,” Heyes added. “Now, are you a man of your word, or aren’t you?”

“Gentlemen, it would be the end of my career—“

“If you welched on us,” Curry finished.

“Quite a dilemma,” Heyes commented. “I almost feel sorry for you. You live up to your word and maybe you’ll need to find a new job. You welch on us, and maybe you’ll need to find a new territory to live in.”

“What are you talking about, Mr. Heyes?”

“Publicity.” Heyes smiled and leaned back in his chair. “See, it’s hard enough on a politician when his rich croneys turn against him, but imagine how hard it is on a man when everyone else in Wyoming, from newspaper publishers on down, turn against him. When his neighbors despise him, when his friends don’t trust him any more, when tradesmen don’t want to do business with him, all because they know he’s a liar.”

“A man couldn’t live like that,” Curry observed.

“No, he couldn’t. As Shakespeare wrote, ‘He who steals my purse steals trash. He who steals my good name steals all.’”

“In other words, Mr. Warren, you welch on us, we’re gonna let the whole territory know about it. There isn’t a newspaper in Wyoming that wouldn’t give us front-page coverage if we came to them with this story.”

“News like this would reach all the way back to Washington,” Lom added. “Wonder what President Cleveland’s reaction would be?”

The governor ran a shaking hand across his mouth. “Nobody would believe you.”

“Wouldn’t they?” Curry prodded.

“They wouldn’t have to. We’ve got eleven upright citizens just waiting to tell the newspapers everything they know about us. They’re all in Cheyenne right now, as a matter of fact.” Heyes checked his pocket watch, then looked over at his partner. “It’s seven-thirty. How fast do you think we could get the publisher of the Cheyenne Sentinel over here, considering he’s probably enjoying his supper right about now?”

“Oh, just a few minutes faster than it would take us to telegraph the Laramie Bugle and the Denver Post and—“

“Don’t do it,” Heyes pointed at the governor’s left hand, which froze just inches from the panic button attached to the underside of the great desk. “You arrest us now, we won’t have to wire the newspapers. They’ll be beating down your door by eight o’clock.”

“Don’t threaten me, Mr. Heyes. Have you seen the inside of a penitentiary? Well, you’re about to.” Warren’s hand dropped to the button.

*********************************************

At least fifty newspapermen and curiosity-seekers were crammed into the elegant office of J. Carmichael Griffith, attorney at law; dozens more in the street craned their necks to see what was going on. Griffith pounded his fist on his desk. “Gentlemen, gentlemen!” The noise died down quickly; this was too important a story to miss hearing.

Griffith motioned for Lom to squeeze forward. “Gentlemen of the press, I’m J. Carmichael Griffith and I’ve been asked to represent Hannibal Heyes and Jedediah Curry. And this is Sheriff Lom Trevors of Converse County, Wyoming.”

“Not for long, I’m afraid,” Lom admitted. “After today, I won’t be able to get elected street sweeper. But sometimes a man has to do the right thing no matter what it costs. And that’s why I’m here: to tell you about a coward who backed down when he was asked to do the right thing. A welcher, a liar, a con man who pulled a confidence game every bit as bad as any outlaw ever tried. This from a man who was appointed to protect the law!”

Murmurs became shouts; it was several minutes before the noise fell enough decibels for Lom to continue. “On April 15, 1886, in his private office in the governor’s mansion, Francis Warren made a deal with me, the Kid and Heyes. One year, he said; if Heyes and Curry would go straight, swear to never commit another crime, and prove it by staying clean for one year, then he’d grant them an amnesty. That was three years ago. Those boys have lived up to their word, but every time we’ve gone back to Warren to ask him to do the same, he finds some mealy-mouthed excuse to welch out. And now where are Curry and Heyes? In the penitentiary, because Francis Warren had them arrested, like the coward he is, instead of keeping his promise. Is this the kind of man you want in office? A liar and a cheat?”

As shouts broke out, Griffith banged on his desk again. “Gentlemen! Please! Now you’ve heard the testimony of Sheriff Trevors, a man who stands to gain nothing and may lose everything in the interest of disclosing the truth. But I don’t expect you to take his word alone. I have eleven witnesses, all of them outstanding, upright citizens, respected in their communities, and none of them with anything to gain by deception. These witnesses will tell you their individual stories of how they came to know and respect Heyes and Curry—know them as truly reformed men. After you hear their stories, we ask that you do the right thing too and demand that Warren the Welcher be removed from office and that his successor grant the amnesty that was promised to these deserving boys, three long years ago!”

Link

ASJ Collection

Chapter list for