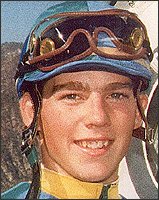

Tyler Baze was born into a family of Washington race trackers seemingly 13 miles east of nowhere. He grew up on the road to someplace else; on the road to Portland, Spokane and Vancouver -- on the road to Canterbury Downs and county fairs and bullring racetracks that don't exist anymore. His playpens were tack rooms and horse stalls. The forts where Tyler and two brothers battled the cowboys and Indians of childhood were secreted under countertops of roadside cafes.

Tyler Baze was born into a family of Washington race trackers seemingly 13 miles east of nowhere. He grew up on the road to someplace else; on the road to Portland, Spokane and Vancouver -- on the road to Canterbury Downs and county fairs and bullring racetracks that don't exist anymore. His playpens were tack rooms and horse stalls. The forts where Tyler and two brothers battled the cowboys and Indians of childhood were secreted under countertops of roadside cafes.

Tyler got his first baths in horse buckets. His father Earl shod horses and worked on starting gates and hauled horses. Together with wife Cammie, they saddle-broke yearlings. The days began at 4 a.m. and didn't end until 10 at night. It was seven days a week with no time off and you did any job that needed doing because that's the way life was on the backstretch of America's minor racetracks.

And they loved it.

"Oh, I wouldn't have traded those days for anything," Cammie recalls. "Nowadays, with all the rules and regulations about kids at the track, we never would have made it. Back then though, that's the way it was. When it got cold, sometimes we had to dress up the boys in snowsuits and lock them in a horse stall for safety. But most times we set them up in a warm tack room with cribs and playpens.

"People frown on raising kids at the track, but we're proud of being race trackers. We never had much, but Earl was with his boys every day and I loved that. The kids adored him."

On June 4, 1980, Cammie, then a jockey, fell in a race and the field ran over her body. Severely injured, her riding career over, she settled down with her family on a little three-acre farm near Graham.

Cammie is a dental assistant now.

Tyler Baze never went to public high school; he was home-schooled from junior high on. At the age of 12 or 13, he traded a cow for a camp trailer and dreamed of hitting the road on his own.

Cammie laughs. "We thought he was on the way out the door early when he traded in that cow -- Tyler was always the one I had to keep my thumb on. He was loud and he was outgoing and he had a mind of his own.

"It was about 15, when he started getting on horses, that we really lost him. Earl and I disagree somewhat about the circumstances, but one day a horse we had named O.B. Slewy ran off with Tyler -- the mare must've gone five times around the track and Tyler's eyes were big as saucers. But he hung on for dear life."

Tyler Baze hung on, indeed.

He mucked stalls for his grandpa Carl, but dreamed of bigger things. He got a job with trainer Mike Puhich. He kept his eyes open, his mouth shut and worked like a kid possessed.

Then he got the break of a lifetime and ran with it.

Impressed with the young man's work ethic, Puhich contacted his uncle Ivan, a jockey agent at Santa Anita. Ivan agreed to launch Tyler's riding career -- under certain conditions

As reported in the Daily Racing Form, Puhich, a former Marine, sat the kid down for a talk.

"Tyler, you're 16," Puhich said. "I'm about to steal something you'll never get back. You may become a great jockey, but I'm going to steal your youth."

Tyler rode his first winner on Halloween 1999. In the ensuing winter, Baze rode more than 500 horses at Turf Paradise in Phoenix. He returned with a vengeance to Southern California in the spring of 2000, and rode away with an Eclipse Award as the nation's top apprentice jockey.

Trainer Bob Baffert says of Baze, "I can see the look in his eyes -- it's nice to have a jockey who does what you ask."

Trainer Bob Baffert says of Baze, "I can see the look in his eyes -- it's nice to have a jockey who does what you ask."

That's fine, but in the competitive racing world, actions speak louder than words. Tyler spoke volumes when 35-1 shot Indian Express gave his uncle Gary Stevens (aboard Buddy Gil) all he could handle down the stretch in the Santa Anita Derby.

The young jock has the stuff to make any dad proud. In Earl Baze's case, try ecstatic.

Tyler's father is an articulate and charming presence on the Emerald Downs backstretch. He still shoes horses and works on the starting gate. In his back pocket (along with the obligatory Daily Racing Form) is a battered copy of "Paradise Lost."

"When my kids were young, I used to tell them you could be anything you wanted to be -- anything," Earl Baze says. "One of my boys wanted to be an astronaut. Sometimes when they drifted off to sleep wherever we were -- half singing, half talking, half crazy, I guess -- I used to whisper maybe one day they might fly their old man to the moon."

His voice breaks, then a moment of silence. Finally Earl says softly, "Now look at this -- I'm off with my wife and family to Kentucky tomorrow. On Saturday, my kid is gonna fly us to the moon."

By phone, Tyler Baze is reserved but polite; the scribe hears a sense of relentless purpose in the jockey's voice. When asked about his father, he says curtly, "My dad never had some of life's opportunities, but now he will."

Does his horse have an honest chance against the likes of Empire Maker and Buddy Gil?

"I think he's the best horse, period," he says. "I think he'll run all day; he doesn't like to be passed by anybody. Neither do I, but I listen to what Mr. Baffert wants. I'll settle the horse into the right spot, and we'll see what happens."

In his no-nonsense vernacular resides the raw will of a young man raised on roads leading somewhere else who somehow always knew where he was headed.

Today, Tyler Baze climbs aboard Indian Express and has an honest shot to win the Kentucky Derby. Most suspect the horse will be gunning for the lead. If the horse gets a good trip, anything, everything, is possible.

Even a trip to the moon

Back to Articles