Minstrel and medicine

shows gave whites an opportunity to be introduced to and explore

the culture of blacks with the excuse of show business to fall

back on. This section describes how these shows began improving

the relationship between blacks and whites by stretching it beyond

the master and slave relationship even before the Civil War.

Minstrel shows were

musical events often featuring white performers who painted their

faces and dressed up like blacks. Beginning in the 1830s, minstrel

shows were popular all over the United States and their influence

on race relations remains ill-defined. On the one hand, they gave

many Americans their first sampling of black music1.

Whites in blackface traveled the country playing music that they

had heard performed by blacks living on plantations in the South2.

On the other hand, they operated to feed the white stereotype

of blacks. However, if it is true that imitation is the utmost

form of flattery, then these shows were evidence of white's attraction

and fondness for black culture. Francis Davis, author of The

History of the Blues, described these shows as "a world

in which black could be white, white could be black, anything

could be itself and simultaneously its opposite3."

There were many white actors in the shows who genuinely appreciated

black musical form and took pride in their authentic portrayal

of black men and women during the shows. Davis asserts that it

was these black-faced whites who eventually made it possible for

blacks to participate in the performances. The earliest black

minstrel to gain distinction was William Henry Lane. He was a

dancer in the 1840s well known for his limber moves and acclaimed

in the novel American Notes by Charles Dickens4.

Lillie Mae Glover, known as Memphis Ma Rainey, said of her travels,

"We'd go to places where they'd never seen a colored person

before. I remember once in Illinois, when we rolled into this

little town, they thought we were no-tailed bears5!"

Medicine shows were

extremely popular in America around the turn-of-the-century. Many

white country blues performers started out as  traveling songsters. Among these are

Roy Acuff, Dock Boggs, Fiddling John Carson, Frank Hutchinson,

and Uncle Dave Macon. These shows influenced race relations because

they featured and entertained blacks and whites. One of the most

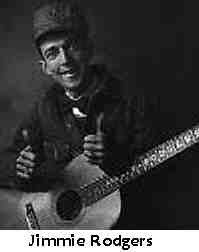

famous medicine show songsters was Jimmie Rodgers, also known

as the father of hillbilly or country and western music. Rodgers's

career began in medicine shows where he occasionally put on blackface

and frequently played with Frank Stokes, a black songster of Memphis

from whom he is thought to have acquired much of his song collection.

He traveling songsters. Among these are

Roy Acuff, Dock Boggs, Fiddling John Carson, Frank Hutchinson,

and Uncle Dave Macon. These shows influenced race relations because

they featured and entertained blacks and whites. One of the most

famous medicine show songsters was Jimmie Rodgers, also known

as the father of hillbilly or country and western music. Rodgers's

career began in medicine shows where he occasionally put on blackface

and frequently played with Frank Stokes, a black songster of Memphis

from whom he is thought to have acquired much of his song collection.

He  demonstrated

his indebtedness to black music in songs such as his "Blue

Yodels." While borrowing techniques and learning from blues

artists, Rodgers was also influential to bands such as the Mississippi

Sheiks. In 1930, the Sheiks did "Yodeling, Fiddling Blues"

which could be a tribute to Rodgers6. demonstrated

his indebtedness to black music in songs such as his "Blue

Yodels." While borrowing techniques and learning from blues

artists, Rodgers was also influential to bands such as the Mississippi

Sheiks. In 1930, the Sheiks did "Yodeling, Fiddling Blues"

which could be a tribute to Rodgers6.

Like the minstrel

shows, the medicine shows often involved blackface performances

and were also a place where whites and blacks could share something

- music and entertainment. Their popularity in America began around

the turn-of-the-century and continued after the Civil War (1860-1865)

and through the Reconstruction period (1865-1877). These shows

were the birthplace of both country and blues. The emancipation

of slaves gave the black musicians, typically referred to as songsters,

the power to travel around and actually make a living playing

music. Their song collection included tunes both black and white

in origin. They played country dance pieces, minstrel songs, spirituals,

and ballads7. William Ivey of the Country Music Foundation

confirms the existence of a common repertoire between the early

country musicians and the early blues musicians forcing a type

of business relationship even at the peak of segregation8.

The noted blues historian, Robert Palmer, says "the music

of the songsters and musicians shared a number of traits with

white country music, with musicians of each race borrowing freely

from the other. But even though many white and black songs were

similar, black performing style, with its grainy vocal textures

and emphasis on rhythmic momentum, remained distinctive9."

It was this distinction that made black entertainers indispensable

and continued to cultivate white appreciation for black music.

1. Davis,

37

2. Palmer, 32

3. Davis, 37

4. Davis, 37

5. Bane, 66

6. Davis, 37

7. Palmer, 40-41

8. Bane, 83

9. Palmer, 41

Back to top Back to top

|