No one will argue

that the life of a black man in the 19th and 20th centuries has

been burdensome. These days we can only imagine how difficult

it must have been to be so oppressed. Many whites saw blacks as

intruders with little to offer other than cheap labor. However,

the black musician seemed to enjoy a slightly better lifestyle

over other black workers, which is evidence of a change in this

opinion. This section explores examples and causes behind the

improved lifestyles of black musicians and how they signal the

genesis of an improvement in race relations between whites and

blacks.

Listen

to Sammy Blue, a blues musician from Atlanta, GA, describe blues

originating as a form of therapy for blacks.

Almost as soon as

the slaves arrived, they began forming bands. These bands featured

a variety of instruments including homemade lutes, percussion

instruments, and flutes or fifes. They were also the artistic

force behind the blackface minstrel shows that were soon to become

greatly popular. Experts find evidence of white appreciation for

early black music in the way whites treated those workers who

were musically talented. Robert Palmer, author of Deep Blues,

mentions the Senegambians in particular who were admired for their

musical ability and allowed special privileges on many plantations.

They were granted light housework while slaves from other African

regions were made to complete the harsh fieldwork1.

In the early 19th century, advertisements would point out the

musical talents of the slaves who were for sale knowing that would

put them in higher demand2.

This treatment continued

into the twentieth century. The farmers who were also musicians

were paid an additional amount of money, however small it was,

and given food and whiskey for their services. Historians again

presume that this compensation and preferential treatment was

more evidence that whites appreciated the musical talent of these

blacks. The white landowners even supported the black Saturday

night dances, reportedly because they felt that blacks needed

an outlet for their energy. Congregating at parties was a good

way for blacks to relax and let loose after a week of tough labor3.

Blues music was not

only an essential element of many religious and secular events

for blacks, but it was a substantial source of entertainment for

whites as well. Performers were able use the same repertoire when

entertaining either race. Robert Wilkins, a country blues artist

from Mississippi, began his career as a performer in 1913 while

entertaining whites and blacks with a similar collection of songs4.

Sam Chatmon, another country blues artist from Mississippi and

a member of the famous Chatmon family, once said, "Mighty

seldom I played for coloreds. They didn't have nothing to hire

you with5." The main focus of the bluesmen at

this time was to keep the audience happy, which meant playing

anything they wanted to hear, whether it be spirituals, dance

tunes, or popular hits. Blind Lemon Jefferson, a Texan who became

very well known for his acoustic blues during the years prior

to the Depression, impressed white and black musicians and audiences

alike6. It was his popularity in 1926 that revealed

to the record companies that a rural blues market existed7.

As with the Senegambians

years before, those who possessed the talent during this time

period enjoyed a better life. Though it never made a man rich,

the blues of this early period offered a lifestyle which was considerably

more comfortable than that of a farmer, the typical line of work

during this time. It allowed its practitioners to make more of

their own decisions. A musician could come and go as he pleased

and never had to take orders from a man paying him next to nothing

to work his fingers to the bone8. Listen to one of the reasons Chicago

Bob, a blues artist from Baton Rouge, LA, became a musician.

Charley Patton is an example

of a bluesman living as a semi-professional entertainer, glad

to escape the hard field labor9. Will Dockery was the

owner of a plantation in Sunflower County, Mississippi, where

Charley Patton's father moved his family around 1897. Dockery's

plantation was a town in itself. He had his own stores, cotton

gins, post office, medical clinic, cemetery, and train station.

He had no use for the music of the blacks, but his attitude was

not the standard of that day. Conversely, Dockery's good friend

William Howard Stovall Charley Patton is an example

of a bluesman living as a semi-professional entertainer, glad

to escape the hard field labor9. Will Dockery was the

owner of a plantation in Sunflower County, Mississippi, where

Charley Patton's father moved his family around 1897. Dockery's

plantation was a town in itself. He had his own stores, cotton

gins, post office, medical clinic, cemetery, and train station.

He had no use for the music of the blacks, but his attitude was

not the standard of that day. Conversely, Dockery's good friend

William Howard Stovall  employed The Mississippi Sheiks,

which included as part of its lineup Bo Carter, Lonnie Chatmon,

and Walter Vinson in different arrangements, to act as personal

songsters to him. Patton was eventually discharged from Dockery's

plantation and was employed by George Kirkland, another plantation

owner just a few miles down the road, who put him to work specifically

as a musician and released him from other work10. employed The Mississippi Sheiks,

which included as part of its lineup Bo Carter, Lonnie Chatmon,

and Walter Vinson in different arrangements, to act as personal

songsters to him. Patton was eventually discharged from Dockery's

plantation and was employed by George Kirkland, another plantation

owner just a few miles down the road, who put him to work specifically

as a musician and released him from other work10.

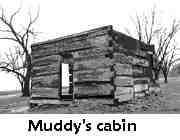

Muddy Waters also

resided on Stovall's plantation in a cabin  that transformed into a juke

house on weekends. Muddy was famous for making the best moonshine

for miles around. His juke house was moderately, yet steadily,

lucrative which was a welcomed addition to the 22 ½ cents

an hour he made as a tractor driver. He also brought in a little

extra by selling his liquor to white supervisors and performing

at house parties11. that transformed into a juke

house on weekends. Muddy was famous for making the best moonshine

for miles around. His juke house was moderately, yet steadily,

lucrative which was a welcomed addition to the 22 ½ cents

an hour he made as a tractor driver. He also brought in a little

extra by selling his liquor to white supervisors and performing

at house parties11.

Numerous artists echo

this story of entertaining white people. Jesse Mae Hemphill remembers:

My granddaddy

would play all kinds of songs…All of the white folk were

crazy about him and the children. He was friendly with everybody,

but he would play more for white people round here. At their

houses for them big dances, the rich white folk would get him

to play, and all three of the girls and me, they would go tell

him, let them all come over there. They liked to do waltzes.

Square dances. Granddaddy would call and they would do it…When

it was cold we'd go to somebody's house, we didn't care who they

was, we'd go up and knock and tell them we had music - y'all

play music, come on in, play me a piece. We'd go in and play

and sometimes stay two, three days - they glad to have us. Wouldn't

charge us or nothing12.

Honeyboy Edwards describes

white patrons of those days:

It was some white

people down there at the time was mean, and I played for a lot

of white dances down there and they treated me real nice, they'd

bring me back home in the car, pay me what they said they was

gonna pay me, give me my drinks and my meal free13.

Robert Lockwood remembers life in the early

1900s: Robert Lockwood remembers life in the early

1900s:

"Where I

grew up, my people was, you could say, middle class livers -

everybody had their own farms and stuff, so nobody forced nobody

to go to no field. People on both sides of my family had their

own little plantations. But I ran into some of that shit in Mississippi,

when we got locked up for vagrancy. They would just pick you

up - it was a law-breaking thing to not be in the field. They

locked us up in Sardis, MS. We did not have to do any work, nothing

like that - they just locked us up because in that part of MS

they did not have any juke boxes, and they locked us up to hear

us play! I understood that after it was all over, they locked

us up because they didn't have music and didn't allow jukeboxes

in Sardi, Como, and Batesville. They locked us up because we

were sounding very good, and they would take us serenading, the

people would give us money and they would give the money to us.

When they turned us out of jail we had over $500 apiece, that

was a lot of money at that time. And we were eating in restaurants.

It was…strange14."

Listen to

a comment made by Chicago Bob about the treatment Louis Armstrong

received while playing in the homes of whites.

1. Palmer,

32-33

2. Davis, 27-28

3. Titon, 24, 57-59

4. Titon, 30

5. Davis, 27-28

6. Titon, 30

7. Davis, 38

8. Titon, 57-59

9. Titon, 58

10. Davis, 58

11. Palmer, 3-4

12. Trynka, 22-23

13. Trynka, 23

14. Trynka, 34-35

Back to top Back to top

|