Ross Bleckner

has been featured in

Architectural

Digest Artforum Art

in America Artnet

Art News

Flash Art Vivre

Angelfire

presents Ross Bleckner

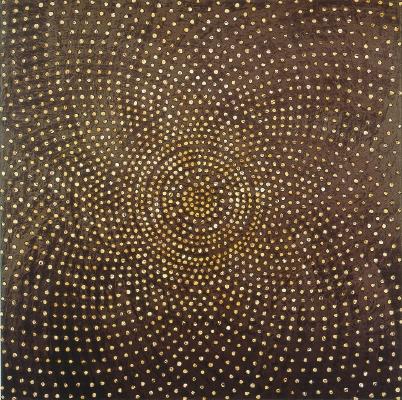

Memorial I, Oil and Wax on Linen, 96 x 120", © 1994 Ross Bleckner

Ross Bleckner at Mary Boone

Art in America

– November 1996

The canvases in the big room of

Mary Boone’s snappy new Midtown gallery were mostly inflected with saturated

and burnt colors-yellow, orange, sienna, magenta, jade. The effect was heavy,

autumnal perhaps intentionally cloying. Bleckner’s confectionery whites

really popped across the darkened space, perhaps because each shape is so

tonally developed and is so often made to vibrate against a smudged black

contour.

The Hope For News

depicts a big, sad sunflower that fills the vertical format with its culturally

freighted sense of melancholy, the sunflower being a well-known surrogate

for van Gogh’s suffering. Now Bleckner’s image of a burnt yellow orb is so

full of atmospheric space and air that it in turn suggests a nod to earlier

abstractionists like Dan Christensen, whose airbrushed arabesques were especially

popular in the late 1960s and early ‘70s when Bleckner was just coming of

age. Yet the artist gets his own form of abstracted petulance going in the

precisely rendered forms of in-turning, desiccated fronds, almost as if the

sunflower was sporting a Titus haircut.

The canvases in the smaller side

gallery mark the transition of the artist’s signature dot from puffball to

bubble. In color they are altogether paler, more rubbed-down and limpid than

the other works, and in mood, they are rather more buoyant.

In Sickness and In Health is the fullest achievement in all regards. With its irregular network of

transparent globule forms, through which one can glimpse a secondary pattern

of white orbs, with here and there an emerging floral shape, the painting

manages to combine and synthesize all of Bleckner’s often seemingly disparate

genres. It is at once a stringent abstraction, a syrupy flower painting and

a slightly loony latter-day Symbolist allegory of germination. Bleckner here

attains a virtuoso level of glazing in his community of transparent lily-pad

forms; not since Joseph Raffael’s large field paintings of the ‘70s has there

been such a maniacally crafted approach to abstraction. In the midst of their

exquisite melancholy, these new paintings look to be among the lightest, happiest

and certainly most masterful things Bleckner has done in years.

NEW YORK - Ross Bleckner's paintings

synthesize, sometimes uneasily, two major themes of modernism: high moral

seriousness and ironic sensuality and artifice. Like those of the Symbolists

a century ago, his earlier paintings transformed old-fashioned imagery - chandeliers,

urns, bouquets - into nostalgic meditations on memory and loss. Since the

early 1990s, Bleckner has moved from objects to decorative, biomorphic patterns

made up of dots and flowers to convey an urgent melancholy.

In his most recent paintings, showing

at the Mary Boone Gallery

(745 Fifth Avenue) and at Lehmann

Maupin

(29 Greene Street) through December 19, the artist's urgency reveals itself

as a concern about mortality, evidenced in representational depictions of

cells, corpuscles and protozoic creatures. Bleckner describes this as the

"molecular structure that lies beneath the skin of my images." In muted colors,

the large-scale works, priced at $90,000 to $135,000, resemble a series of

petri dishes, each containing strikingly beautiful, abstract life-forms.

Overexpression, shown left, initially resembles mossy stones in a stream bed; on closer

inspection, the shapes reveal themselves as cells - at least one of which

appears to be carcinogenic. "I'm concerned with mutation, "Bleckner says,

"and the idea of something beautiful, like a cell, mutating into something

treacherous." Indeed, the painting is disturbing and mesmerizing, like a portentous

medical report.

For this viewer, that portent is

AIDS. But Bleckner also sees his work as addressing other issues: diseases

that come with aging and, ultimately, death - in effect, what baby boomers

have always felt exempt from. "I want to deal with the beauty and fragility

of our lives - how vulnerable we are," he says. The Symbolists, in their time,

were fascinated by the aesthetics of mortality. Bleckner, carrying on that

tradition, presents us with a bracing memento mori for our times.

On the eve of a major retrospective,

painter Ross Bleckner

has to face an unpleasant fact. He's just too, too popular.

Falling Birds

- New York Magazine

- February 20, 1995

Call it art-world sniping, but denigration

of Bleckner has become routine, even obligatory ever since that August evening

in 1993 when Bleckner threw a benefit party for the Community Research Initiative

on AIDS (CRIA) on his Sagaponack estate (formerly Truman Capote's summer

retreat), and Barry Diller, Bianca Jagger, and "Styles of the Times" showed

up. Suddenly, Bleckner, the gay activist, the mentor to young artist, the

sweet, awkward, again ingenue still learning to be what his dealer, Mary

Boone, once advised him to be-"a big artist"-had become something else: A

high society fund-raiser. A schmoozer. A socialite. An opportunist.

Bleckner means a lot of things to

a lot of people, which is one reason we're lingering on the subject. As a

rather astoundingly large mid-career retrospective of some 70 paintings goes

up at the Guggenheim in March, Bleckner, at 45, seems on the verge of apotheosis,

a man about to experience genuine American fame. (That he's an early beneficiary

of a new Guggenheim policy mandating more mid-career surveys of American

artists doesn't undermine what amounts to the sanctification of his work.)

Yet no major figure on the art scene since Andy Warhol has inspired such

knee-jerk dismissal on the basis of his social life-and at least Warhol was

making smirky art about celebrity. There's a little irony in Bleckner's eager

embrace of society, and that makes people uneasy. "Artists shouldn't be starving

in the gutter," says a prominent SoHo art dealer who asked not to be identified,

"but they should aspire higher than the consumer culture they're supposed

to transcend."

Envy abounds. It's even murmured

that Bleckner, the son of relatively well-to-do parents from Long Island,

did some palm-greasing along the way. He did, in fact, lend money to art critic

Gary Indiana when the writer was broke in the latter half of the eighties,

two years after Indiana gave Bleckner a good review in The Village Voice.

Otherwise, Bleckner's record looks squeaky-clean, and he doesn't seem the

type to use such strategies, anyway. The Blecknerian assault is charmingly

direct; You see him sizing you up-your age, sexual preference, intelligence,

knowledge about art, potential friendliness or unfriendliness. He makes the

give-and-take of high-end networking seem natural, even appealing; Benignly

cunning in a Bill Clinton sort of way, he finds the middle ground, connects

with you, makes deals with you. He has never "strategized with an art dealer,"

he says sharply, but as his friend the artist Barbara Kruger puts it, "Ross

has always had a very examined relationship to power. If you understand power,

and you're smart, you never believe your own hype. You don't get deluded."

There are no books in the studio;

the paint tubes are neatly aligned; turpentine sits in burnished copper bowls

on polished wooden tables. In a large white room that forms on half of the

studio, Bleckner has put five new paintings up for view. Up on the top floor,

a quiet patio garden resembles a landscape miniature; in the apartment, the

towels draped over a radiator look as though they were cast in bronze. Bleckner's

dachshund, Mini, wiggles around happily. It's like a vast still life-everything

is studied, everything is considered. Raw authenticity is not Bleckner's style.

Both studio and apartment are in

a building he owns-six run-down floors on a scruffy block on White Street.

The real-estate holding is the keystone to Bleckner's rich-kid image, since

his father lent him the money to buy it in 1974, when he was first starting

out as an artist. In a 1984 review of a show at Mary Boone, for example, critic

Brooks Adams wrote that "perhaps because he does not have to paint for a

living, Bleckner can afford to have the last laugh." On the other hand, his

father paid less than $100,000 for the building-the price of a studio apartment

today-and the criticism sounds odd coming from a community where so many

are renters or marry well. "It's a very sixties notion, that to be an artist

you have to have suffered," says Michael Goff, editor-in-chief of Out and

one of Bleckner's protégés.

The suburb Bleckner grew up in-Hewlett

Harbor, in one of the famous Five Towns-was indeed, in the 1960s, a warehouse

for much of Manhattan's freshly accumulated wealth. What he remembers of his

childhood and adolescence, however, is crashing his Pontiac GTO and a sense

of alienation he later described in Art in America as "a certain sadness"-

the estrangement he felt as a gay youth: "I would mimic the social strategies

I saw, but I knew that for me they didn't have resonance."

After graduating George W. Hewlett

High School in 1967-other students from the era included Donna Karan; Sam

LeFrak's daughter Francine, the producer; the photographer Susan Meiseles;

and Art & Auction editor Bruce Wolmer-he enrolled at New York University,

eventually transferring to its studio-art program. He considered a career

in journalism, but also "thought about being an artist a long time," he says.

"It's scary to take the plunge." He adds, "It came to me during an acid trip."

Bleckner's education was eclectic.

He studied with conceptualist Sol Lewitt and photo-realist Chuck Close at

NYU, then did graduate work at CalArts, where John Baldessari held sway with

his own highly theoretical brand of conceptual art. He returned to New York

in 1973. "I first met Ross in the mid-seventies," Julian Schnabel remembers.

"I needed a job and he needed the paint on his ceiling scraped off. It was

horrible, thankless work, and after about half an hour, I said I didn't want

to do it. He said he wouldn't want to, either. From that day on, we were the

best of friends." Schnabel invited Bleckner to stay at his studio in Texas

for his very first show, at Houston's Contemporary Arts Museum in 1976. Things

went a little awry, though. "At dinner before my opening, my mother was complaining

about my attire-she didn't like my leather jacket," says Schnabel. "So I

got angry, walked out of the restaurant, and left Ross at the table." Bleckner

finishes the story: "I ended up escorting Julian's parents to their son's

first opening."

Nowadays, Bleckner likes to pretend

that he didn't crawl out of his studio until the later eighties, but the truth

is that both his remarkable discipline and his love of schmoozing were manifest

early on. That night, Bleckner hung out at the Mudd Club-conveniently located

right downstairs, since he'd rented the owners the space in his building-earning

the attention of dedicated clubbers like Stephen Saba, the nightlife critic

for Details. "That was in the Mudd club's heyday," Saban recalls wistfully.

"Bleckner was always there." Says Kruger: "Ross always zigzagged between being

very social and pulling back. I remember him saying all the time, 'I'd be

a recluse if there weren't so many people around.' "

By day, however, Bleckner worked

in his studio, churning out pastiches in a laborious quest for a style. "Ross

represents an interesting confluence of all these styles floating around in

the mid to late seventies," says critic Lisa Liebmann, who just published

a book on David Salle. "He represented an abstract flip side of New Image

painting, and then he was influenced by the 1979 [Cy] Twombly show, which

was seen as a failure at the time but influenced a lot of younger painters."

He had a few shows in some small and now-forgotten galleries, with only middling

success. "Whenever you wanted to talk to a dealer, they were sick," he recalls.

"I used to think every dealer in New York was sick." In 1978, he met Mary

Boone, a young dealer who was just about to start her own gallery. At his

urging, she also signed on his friends Schnabel, Kruger, and Salle, who (along

with Eric Fischl) would form the nucleus of her celebrated eighties stable.

"I saved Ross's life," Schnabel

explains, "several time. The night after my opening at Mary's, I went to Ross's

loft and found him unconscious, his leg hanging by a piece of skin." A falling

counterweight had pushed over a ladder, which had dragged Bleckner's leg

into the open elevator shaft and severed the main artery. " We took him to

the emergency room at Beekman Hospital, and he was lying around waiting for

a doctor while there was no pulse in his foot. Luckily, I reached my cousin,

who is a vascular surgeon, and we moved him into St. Vincent's and took Ross

right into microsurgery.

Bleckner kept his leg, but the episode

ushered in a bleak phase of his career. While Salle and Schnabel soared.

Bleckner stalled. His "stripe painting"-op-art candy striped on a Barnett

Newman scale-bombed on arrival at Boone in 1981. "People just thought I was

perpetuating a joke," Bleckner later told FlashArt. Boone's interest in Bleckner

dwindled rapidly until, Schnabel says, he intervened: "I told Mary, 'If you

cancel his show, I'm going to leave the gallery.' "Apparently he was persuasive,

and Bleckner's next (1983) show would sell out, although Schnabel is still

dismissive: "It was frustrating, because I really believed in Ross's work.

When people came to my studio, I'd often show them his work. She must be

doing something right if he's still showing with her after fifteen years,

but this stuff about her or anyone else making someone's career is a load

of horseshit." (Boone denies that Schnabel ever confronted her; Bleckner says

he doesn't know.)

It wouldn't have been hard for Schnabel

to defend Bleckner, if in fact that's what happened. Bleckner's dense, meditative,

nice paintings posed no threat to Schnabel's aggressive, splashy Neo-Expressionist

aesthetic. But Bleckner went even further than Schnabel did, actively seeking

out and helping young artist who could conceivably become his competitors,

buying their work, introducing them to clients. His was "a kind of godfather

role," says dealer Perry Rubenstein. "Ross will embrace something that is

subconsciously threatening to him. And most artists don't do that. They surround

themselves with artist who reflect some part of their work and don't threaten

them."

Thirty-two-year-old Alexis Rockman,

whose hallucinatory zoological paintings have made him an up-and-coming star

of the next generation, managed to turn a brief and ill-fated apprenticeship

into a friendship. "I was a miserable assistant, and Ross fired me after three

months," he says. "But we became very good friends. Ross taught me a lot

about how to be an artist, both socially and professionally-how to make myself

available, how not to alienate anybody."

The mentoring paid off: As Schnabel

and Salle began living like movie stars (and, indeed, preparing to become

movie directors), Bleckner was quietly being taken up by the East Village

art scene. Peter Halley, a young painter who rejected the kitschy heroics

of Neo-Expressionism for something cooler and more cerebral, wrote in Arts

in the early eighties that Bleckner's striped were a missing link between

a romantic modernism (Mark Rothko, say, or Willem de Kooning) and a doubting

post-modernism (Salle, for instance). Suddenly, younger artists began to tune

in. "He really orchestrated everything brilliantly," says Rockman. "These

younger guys like [painted and International With Monument Gallery director]

Meyer Vaisman and [painter and Nature Morte Gallery director] Peter Nagy started

getting interested in his work, and Ross was smart enough to encourage them.

Not that it wasn't opportunistic, but there was also something genuine."

It was at Nagy's storefront gallery

that Bleckner held his pivotal 1984 show, in which he displayed just one large

painting, which combined text and abstraction. "There was a whole discourse

about the process of making art the Halley and Ashley Bickerton and Sherrie

Levine had reopened," remembers dealer Pat Hearn. "For Ross to use that painting

was really clever." When Sonnabend Gallery brought together four East Village

artist-Halley, Vaisman, Jeff Koons, and Bickerton-for its infamous 1986 "Neo-Geo"

show, Bleckner's coterie was suddenly on top, and Bleckner, whose work was

always more sensual than intellectual, more incidental than theoretical, ended

up riding on the coattails of Neo-Geo, an aridly ideological movement rooted

in half-understood ideas of structuralism. The irony was not lost on him.

"There's always something that somebody looks at as a precedent," he says.

"maybe people got tired of slopping a lot of paint around. If my work looked

fresh to somebody, I never knew, because people were whisked past my shows

to see some ink drippings in he back room."

The idea for this show came to me

during the renovation of this building," says Lisa Dennison, the curator at

the Guggenheim responsible for the Bleckner retrospective. "One day," she

continues, "I climbed up to the skylight, and I was reminded of Ross's dome

painting. I thought of Ross's sense of the sublime quality of light-and one

of the emphases of the renovation was the restoration of the natural light

that previous administrations had blocked out." Bleckner's feel for chiaroscuro

and his darkly luminescent paint (he varnishes his paintings to get that

dim glow) did flower into some sublime works in the past ten years, and Dennison

has the pick of the lot: the dome paintings, candlelike light throbbing in

vast domes; the starry constellation paintings; and the paintings that use

urns and other funereal motifs as an allusion to AIDS.

Despite Bleckner's rich web of social

and professional connections, the show itself betrays less evidence of back-scratching

than usually crops up under close examination of a major exhibition. His

good friend David Geffen did contribute a small amount of money through his

foundation, and recent dinner partner Ron Perelman has shown a great deal

of interest in the Guggenheim lately. But Dennison, the curator, says Ross

kept the influence of collectors upon the exhibition to a minimum. " A lot

of collectors yelled at the two of us, demanding to have their pieces included,"

says Dennison. "Ross couldn't be swayed."

Bleckner's relative independence

from collectors' whims (in this instance, at least) may stem from the fact

that he is much better represented in European collections than in American

ones. Neither Geffen nor Barry Diller-another close friend-has ever bought

a painting. His biggest collector is the late Thomas Ammann, a Swiss dealer

who discovered Bleckner early on, in 1981. Spanish painter Juan Usle explains

Bleckner's Continental appeal: The paintings, he says, "have this kind of

old memory. It's like the light and atmosphere of El Greco's View of Toledo-it's

really close to a European sensibility."

Bleckner may play the social role

of a society painter-a Sargent for our time-but is his art society art? Not

in the narrow sense of a conservative portraiture, certainly, but Bleckner's

art sometimes seems to reflect the concerns of his glamorous circle more than

any personal vision. This seems especially the case with the AIDS-related

work. While undoubtedly sincere, it sometimes has the feeling of those Victorian

marble monuments under weeping willows-it's too perfect, too composed. Bleckner

deserves credit for trying to do something seductive with paint; his shimmering

surfaces are all the more powerful for being impossible to interpret rationally.

But there is a sense of finish to Bleckner's paintings-a slickness-that reduces

some of their gestures to rhetoric rather than passion. As Jerry Saltz writes

in Art in America, it's "more melodramatic than dramatic."

Bleckner's penchant for being all

things to all people deeply informs his recent work. Not only is he catholic

in his choice of influences, but he seems so happy to accommodate that people

from wildly disparate camps accept his as their own. "There's something in

there for everyone," says Lisa Liebmann. "For those who had a formal sense

for abstraction, those looking for a historicized ironic message, and those

who had a romantic sense of fin de siècle."

Bleckner's Zelig-like nature-he's

ubiquitous, yet hard to pindown-underpins his social persona as well. He often

talks about himself with mildly false modesty-it's his way of encouraging

your sympathy. But he seems genuinely needy, too, and this craving for affirmation

does a lot to explain his binge-purge attitude toward celebrity, which has

him swinging wildly between solitude and gala events. "I'm like any other

insecure guy." he says. "I'd rather be in some hypersocial environment where

I can avoid real interaction."

"Part of me wants to say," his friend

Rockman mock-admonishes, " 'Don't worry about getting in the magazines every

two minutes. You're not going to become extinct.' "

Bleckner's insecurity also reveals

itself in a very thin skin. At several points during our interview, he lashed

out at the art press, mentioning in particular reviews in Art in America by

current New York Times critic Roberta Smith and a snide remark in Art &

Auction by Smith's husband, Saltz, to the effect that Bleckner used to be

a painter but is now a socialite. Yet if you go back to these reviews, you

find that they were more or less positive.

What should we make of Bleckner's

famous friends? His friendships with Geffen et al. have to be understood in

the context of his sexual identity: The gay world is a t the core of Bleckner's

many circles, and he's become enmeshed in the tiny power elite that also revolves

around other gay starts. It seems more inevitable than egregious. And a lot

of the other flak just seems unfair. Roy Lichtenstein and Ellsworth Kelly,

for example, are both richer than Bleckner and do just as much schmoozing,

although they do it out of sight. A Lichtenstein painting commands roughly

four times what a Bleckner painting does; the older painter also has a house

in the Hamptons, and also attends the same functions as Ron Perelman (who,

through Marvel Entertainment, underwrote Lichtenstein's Guggenheim show last

year). And so what if Bleckner is socially adept? Success like his does not

occur without someone's working some angle, and Bleckner happens to be a very

good painter who knows how to work the society angle. There are equally good

painters. But here are also plenty of artists Bleckner's age whose only talent

is for schmoozing.

Besides, as Bleckner asserts, and

as his friends confirm, he genuinely adores the people he socializes with.

He's an opportunist with heart: If his favorite people happen to be among

the richest, most powerful, and most glamorous people in America, hey, that's

between God and Ross Bleckner.

The gallery shows are at Lehmann

Maupin in SoHo and at the artist's longtime home base, Mary Boone, on 57th

Street. The Lehmann Maupin show, which includes a soupçon of political

photo-based work (a new tangent for the artist), features some of the best

paintings he has made in years, maybe ever. Seductive, refined, dominated

by his characteristic grisaille palette and infused with a melancholy inner

light, these works treat motifs and effects that the artist has pursued for

years but with a new economy and force.

Thankfully, Mr. Bleckner has jettisoned

the greasily varnished fields dotted with birds, flowers or flares of light

that dominated so many canvases in his 1995 mid-career survey at the Guggenheim

Museum. While those works were often described as memorials to the devastation

wrought by the AIDS epidemic, such meanings seem largely tacked on by admirers.

What really came across was an air of slick Victorian kitschiness.

In these new works, gray-toned expanses

of tiny overlapping shapes suggest tiny cells, the transparent cytoplasm of

larger cells, microscopic views or cross sections of skin or fish scales.

They evoke illness and the body more concretely but also more abstractly than

anything that Mr. Bleckner has done before. They also resurrect his penchant

for Op Art-like effects but seem less a quotation of the earlier style than

an attempt to extend it.

The fields are generated by a real

dazzler of a technique: hundreds of quick, closely spaced bursts from an airbrush

transform still-wet surfaces dotted with circles and spheres into fluctuating

networks of cells and shadowy forms. (Think of Yayoi Kusama nets painted

in the style of Roger Brown's tightly rendered shaded clouds.)

In fact, the new technique is so

dazzling that the first reaction to these paintings may simply be, "How were

these things made?," followed quickly by a close-up examination of the surface,

which doesn't explain much. You can almost forget to back up and look at them

whole, which is something of a weakness. Such mysterious high finish goes

bravely against the grain of most current abstraction's emphasis on self-evident

process; it's even mildly Victorian (we also look closely at paintings by

Edward Burne-Jones or Richard Dadd to try to see how they're made) but with

a contemporary sci-fi edge.

It is not surprising that one of

two paintings titled "Tolerance," in which the little cell-shapes are organized

into a big mandalalike dome or wheel, is the best work here. Its concentric

circles and radiating spokes add a larger purpose to the tiny pulsating units.

In addition, it is more loosely worked: the airbrushed cell-shapes read more

clearly as the little pool-like clearings of paint that they really are. And

they're not continuous; patches of Mr. Bleckner's casually brushed underlayer

remain visible.

Having returned to more abstract

imagery, Mr. Bleckner presents his political conscience as a kind of side

dish. Along one wall at Lehmann Maupin are a series of photographs of page

A3 of the New York Times, all with a major international story appearing beside

an ad for Tiffany's. This kind of appropriation was done much better nearly

20 years ago by some of Mr. Bleckner's contemporaries, among them Richard

Prince and Sarah Charlesworth. In addition, this juxtaposition of images

of harsh reality (war-torn Bosnia, for example) with smug promotions of high-priced

elegance seems disingenuous, considering that Mr. Bleckner's paintings belong

to the second category themselves.

Things deteriorate further at Boone,

where Mr. Bleckner essentially puts his new technique into overproduction,

something he has done before. The addition of stronger colors makes the paintings

seem more obvious and cloying. DNA-like chains of cells come in pleasant shades

of blue, yellow and pink; red is added to other works so that blood cells

and scientific illustrations are evoked. And the airbrush technique seems

to tighten, which means that many of the cells seem to be made of jelly-beans

or beads; suddenly the paintings seem more photo-realist than abstract.

The vodka ads, which also feature

the cell-shape surface, are something like the last straw. In this context,

a motif intended to set off a certain visual and poetic resonance is leveled,

stripped of seriousness and reduced to entertainment. There are very few artists

whose work can travel from art gallery to magazine advertisements and retain

anything close to their character; Andy Warhol, Keith Haring and Barbara

Kruger are possible exceptions. It would be easy to say that Mr. Bleckner

misunderstands his own art if he thinks it can, too, but maybe the misunderstanding

is ours.

The mainstream of today's taste

in abstraction calls for allover patterns rather than, say, a figure/ground

dichotomy (too stodgy) or a single-color field (too academic), a highly refined

sense of surface, and the kind of untouched-by-hands technique that inspires

wonder. People these days like their abstraction impure, for instance, if

as an image it echoes some previous stylistic phenomenon (whether emotionally

charged or just piquantly quotidian) or suggests an origin in some other medium,

like TV or photography. Such associations allow for overtones of nostalgia

without breaking the barrier of cool.

This style originated, pretty much,

with Ross Bleckner's work of the 80's, and it has been adopted in varying

degrees by a wide swathe of younger painters. Two concurrent shows of his

recent work suggests that now Bleckner in turn seems to have been spurred

by the challenge of his young admirer-competitors to push himself to develop

an even slicker, more eye-catching technique, which has (perhaps surprisingly)

resulted in some of his strongest and most expansive paintings. Unlike the

work of most of the young pretenders, though, the best of Bleckner's new paintings

are huge - 10 by 9 feet - as if challenging the spirits of precursors like

Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko as well. And if Bleckner's intention was to

prove that, contrary to all we've ever been taught, slick can also be sublime,

he's pulled it off, at least intermittently.

The AbEx masters were often concerned

with the establishment of a distance and its breakdown. Rothko spoke of seeking

an effect of intimacy, and the same thing is implied in the notice Newman

posted at one of his exhibitions: "There is a tendency to look at large pictures

from a distance. The large pictures in this exhibition are intended to be

seen from a short distance." The intention was not to overpower the viewer

but to create a habitable space of color and light; the same is true with

Bleckner, only his means are different: Instead of broad, open fields of individual

colors, we have vast accumulations of tiny cellular dots, dark at their centers

but shading into brightness at their edges like the shapes in a solarized

photograph. In some of the paintings these cells simply clump together in

such a way that their individual variations in size or ratios of light to

darkness create zones of uneven density. More often, these tiny units are

bunched up so as to create a second order of organic structures, which may

even have nucleus-like centers of a distinct color. In either case, the multiplicity

of minute, irregular patches endows the embracing pictorial field with a

strong feeling of mobility and plasticity, as well as an implicit tactility

quite distinct from the more "optical" expanses of pure color espoused by

Newman or Rothko.

The best of these paintings are

near-grisailles, with just a single color, usually yellow, added to gray and

white of varying shades. (Yellow is an interesting choice, since it evokes

both gladdening associations with solar light and warmth, and dismal ones

of illness and warning.) In the somewhat smaller paintings shown at

Mary Boone Gallery, in which Bleckner threaded a number of colors through and around his cellular

conglomerations, the effect was disturbingly arbitrary, and the cell imagery

was articulated in too literal a fashion. And it was misguided to show some

weak photo-works based on newspaper appropriations à la early Sarah

Charlesworth (seen at Lehmann Maupin). Yet in some of his new paintings Bleckner achieves a unique blend of authority

and sweetness, reaffirming the scope of his project by continuing to change

while remaining true to his beginnings.

Los

Angeles Times The New Yorker

New

York Times Village Voice

Vanity Fair

Botanical

Study, Oil on Linen, 60 x 60", © 1993 Ross

Bleckner

angelfire.com/ny/bleckner

was founded in 1996

as the first publicly

owned website pertaining

specifically to

a historically significant

contemporary painter.

Assembled

by Mark Gibson with

a group of art

connoisseurs to

build a resource about

one of the world's

most celebrated artists.

Providing only the

finest art links on the internet.

Brought to you by

Angelfire, a Lycos Network

Site in no way affiliated

with Ross Bleckner,

rbleckner.com, ACRIA, critical acclaim

personnel, representative

galleries, publishers,

institutions or

museums. Aformentioned parties

had absolutely no

input whatsoever in the

content of these

pages. Captions by Ross

Bleckner taken out

of context from interviews.

Photos copyrighted

by Sebastiano Piras, Clark

Anderson, Luis Sinco

and Carlos Rodriguez.

Featured artworks

copyright © Ross Bleckner

and respective owners.

All rights reserved.

Unauthorized duplication

is a violation of applicable laws.