MUSICIAN Magazine

June 1983

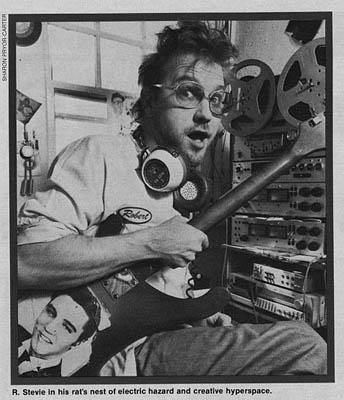

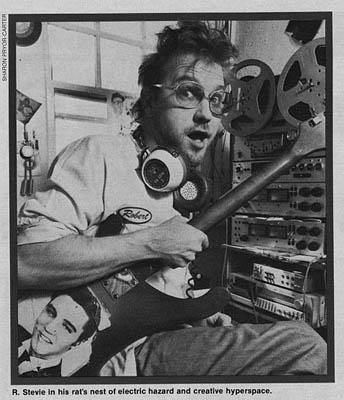

R. Stevie in his rat's nest of electric hazard and creative hyperspace.

[PHOTO BY SHARON PRYOR-CARTER]

(Cue nineteen-guitar feedback fanfare, recorded one line at a time on two quarter-track machines and bounced back and forth until the tape hiss sounds like a steam engine.)

It starts, like a lot of good music stories, on the road. That's where R. Stevie was born, thirty-one years ago. His dad was Bob Moore. The Bob Moore; not a household name, but the bass player on nearly every major release out of Nashville you might care to mention---Red Foley, Willie Nelson, Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis...four sessions a day, that's where you could find Bob Moore. And that's the kind of highly-charged musical atmosphere that R. Stevie grew up in.

He couldn't stand it.

Nowadays he feels somewhat differently, but back then, country music just didn't do it for him. Instead, it was the 60s thing, the Beatles and the English Invasion, that got him to grab a guitar and join garage bands, belting out versions of "Louie, Louie" and "Hang On Sloopy." There was the occasional country session to pay the rent, but it was too easy, too safe. "To this day," he admits, "that's a haunting kind of thing. I could have just stayed there and had all the Cadillacs I wanted, forever."

For better or worse, R. Stevie was not in the right place or time, and the pressure was on. All that eclectic strangeness in his soul demanded an outlet. Ironically enough, it was a job song-plugging for his dad's country-western publishing house that provided the final, perverted push. After a hard day's schlepping grade-B cry-in-your-beer tunes to Nashville's Music Row, what was a poor unintentional renegade to do but plug into the first in a string of cheap stereo tape decks and let it all go? "It was real brash, totally separate. I couldn't have played it for my father."

Maybe not for his dad, but certainly for his uncle, Harry Palmer. Harry had been the mastermind behind a 60s psychedelic group called Ford Theatre, and had an open ear for R. Stevie's blend of pop and passionate experimentation. He acted as a kind of long-distance mentor, helping finance instrument rental and tape time, offering criticism and encouragement in letters and over the phone. Finally, in 1976, Harry assembled some of his favorites from R. Stevie's home tapes and issued them as a very limited edition album (100 copies!) called Phonography. The music on that disc was both raw and wry, alternately forlorn and hysterical and marked with the characteristic sound of massive home overdubbing. Despite the fact that it was not released to the general public, it started getting reviews and a little airplay. (One cut from it, "Theme From A.G.," is a true American oddity---an electric guitar rave-up version of the music from the Andy Griffith Show that is both hysterical and a truly loving homage. There's the paradox of R. Stevie Moore, right there.)

Uncle Harry followed that disc with an EP of four songs from Phonography, which was sold to the public, and then a second album, Delicate Tension. Somewhere in there he also finally tore R. Stevie loose from unsought exile in Nashville and got him to move to New Jersey.

At that point things both happened and didn't happen. The albums went out. The reviews were printed, good reviews, and people in England and France got interested enough to release tracks as part of compilations or in special singles. But the record companies here in the States just weren't biting. R. Stevie, they said, was too weird.

And he was getting weirder. Punk was beginning to happen, and the ears of the boy from Nashville were wide open. Even there, though, he was a maverick's maverick. The punks didn't go for his stuff, either. Maybe it was the occasional Frank Sinatra influence. "It always seemed like all the new wavers were listening to nobody but other new wavers. I was listening to Pere Ubu and the Sex Pistols---but I was also listening to Jim Reeves, 10CC and Brian Wilson."

If by now you've gotten the impression that anything, anything at all, is grist for this fellow's creative mill, you've got it right. He is astonishingly prolific. Ten years of home recording have produced a catalog of sixty different master tapes, tapes which make up kind of a musical diary. Certain threads run through them all---that eclecticism, for example, which means you can never quite be certain what's coming next, and a sense of humor that can twist the middle of even the most self-pitying song. There are pieces of classical music with overdubbed vocals. There are rockers. Ballads. Radio show sign-ons. Synthesizer games. A red-hot cover of "Chantilly Lace" next to a stark sonic tone-poem. Sixty cassettes. Ninety hours of very creative music, not all of it successful, but virtually all of it fascinating by context alone (and usually more; there are tunes here that many richer, more famous musicians would be proud to have written).

For a long time, R. Stevie's preferred work method was to have a friend in Nashville record drum tracks and mail them north. Sometimes he would instruct the drummer to play along with a certain record, but more often than not it was, "Act like something else is happening, and don't get too busy; think three or four minutes." Then over that R. Stevie would overdub basses, guitars, keyboards, more percussion, vocals..."The whole concept was not to bounce tracks, or to multi-track, but to build up generations, which is kind of taboo to most people who record."

This, of course, resulted in a murky hiss that R. Stevie took advantage of instead of avoiding. More recently, influenced by tribal musics and the minimalist philosophies of his current favorites, he's taken to assembling players and recording their sessions---in which they often play unfamiliar instruments---and then working his magic on top of those tracks in a simpler way, sometimes adding no more than spoken words or a bit of sung melody. And yet, even this pattern can't be extrapolated from. His latest tape release, WOMAN/WithOut Mentioning Any Names, has one side of country-influenced acoustic guitar and vocal tunes, recorded in one take into a $35 Panasonic tape recorder, a machine so wasted that its batteries were taped into place. Take that, Bruce Springsteen!

Don't believe it? The worst (best?) is yet to come. R. Stevie Moore's message to the world of recording artists is that it's possible to make your mark even if you don't have forty-eight tracks and a record company footing the bill. He gets by just dandy in one cramped corner of a room, nestled into a rat's nest of old boxes and electrical wiring that resembles nothing so much as the DANGER, DON'T DO THIS TO AN OUTLET drawings they used to show us in fire prevention classes. There's his current main deck, an old Pioneer RTU-11 4-track/2-track, which kind of embarrasses him because it isn't as pure, but which was a steal at $200. An Ampex stereo deck of uncertain vintage and a nonfunctional Sony 640-B (for Beaten To Death, I think) round out the collection.

For mixing there's a Sony MX-8, tiny, an infant among boards, and for a rhythm machine he's got a box from Panasonic with an on/off switch, three pushbuttons and a price tag of $10. His vocal mike is a Sony cardioid he's owned for fifteen years. His headphones are this set of humongous metallic blue cans labelled "Vanco Co-Axial II" on one side. He's bought new Koss and Pioneer headphones, but they're for when other musicians join in. And over in one corner there is a dusty Panasonic Dolby noise reduction unit. Which he doesn't use. "I've had it two years. But I haven't really figured it out yet."

And somehow, with this hodgepodge, the man makes music. Good music. Gives you hope, doesn't it? (The man also plays good music on the radio; he hosts a wonderfully eccentric weekly radio program on North Jersey freeform college station WFMU-FM.)

And for distribution, everything he does is aimed at release on cassette. He even violates another studio taboo and records on both sides of the tape, so that his reels hold precisely ninety minutes. An eccentric approach, but with aid from manager/drummer/fellow DJ Irwin Chusid's sharp ear and criticism, it seems to be working. Double platinum isn't in sight, to be sure, but twenty or so cassette orders per week come in, to be individually duped, decorated, packaged and shipped. And the number of orders is increasing.

That isn't really surprising, though. In the wide-eyed, hungry, D.I.Y. world of the 1980s, it just might be R. Stevie Moore's time to shine.

For more information on his tape catalog, by all means contact R. Stevie Moore at (old address). He'll be glad you did.