by Mitchell Pacelle

Collision with a New York Skyscraper

If audio isn't playing, click here

|

|

Jack Wernli, a staff photographer who snapped celebrities on the observation deck of the Empire State Building, was late again for work on the morning of Saturday, July 28, 1945. He got off the elevator on the 85th floor and tiptoed up the stairs to 86, intent on avoiding his boss. At 9:49 A.M., as he pulled the lever on the time clock, there was a deafening explosion. He figured his boss had rigged a booby trap.

Jack Wernli, a staff photographer who snapped celebrities on the observation deck of the Empire State Building, was late again for work on the morning of Saturday, July 28, 1945. He got off the elevator on the 85th floor and tiptoed up the stairs to 86, intent on avoiding his boss. At 9:49 A.M., as he pulled the lever on the time clock, there was a deafening explosion. He figured his boss had rigged a booby trap.Army Lieutenant Colonel William Smith Jr., a 27-year-old veteran of 34 bombing missions over Germany, had been flying a twin-engine B-25 bomber from Bedford, Massachusetts, to New York's LaGuardia Airport, and had secured permission to continue to Newark, New Jersey.

The fog was blinding. When he dropped down out of the clouds, he found himself approaching a forest of skyscrapers. In a panic, he banked away from the Grand Central Building, then from another tower on Fifth Avenue, only to find himself bearing down on the biggest one of all.

In desperation, he pulled up hard, twisting. The 10-ton bomber plowed into the office of War Relief Services of the National Catholic Welfare Conference on the 78th and 79th floors, 913 feet off the street, tearing a gaping hole in the Empire State Building's north side.

The aircraft's wings sheared off. Its fuselage hammered into an I-beam between elevator shafts, bending it 18 inches inward. The building shuddered. The bomber's fuel tanks exploded, sending brilliant orange flames leaping as high as the observatory and flaming fuel blowing through the offices and cascading down the stairwells.

One of the aircraft's engines torpedoed out the south wall of the building, falling to the roof of a 12-story building on 32nd Street, where it started a fire that demolished the penthouse of noted sculptor Henry Hering, destroying much of his life's work. Fortunately, the artist himself was playing golf at Scarsdale Golf Club. The other engine crashed onto the roof of an empty elevator, sending it plunging to the basement 1,000 feet below.

The Human Cost

Fifteen to 20 female clerical workers for the War Relief Services fled their desks in terror. Only a few reached the safety of the fireproof stairwell. A male coworker either jumped or was blown from a window, landing on a ledge six floors down, where his body was later found.

An elevator operator was blasted out of her cab and burned severely. Two women found her, administered first aid, and turned her over to another elevator operator to transport to the lobby. When the doors closed on that car, the cable snapped with a crack like a rifle, and the two women plunged to the basement.

Firemen cut through its roof, and a 17-year-old Coast Guard apprentice who had dashed into the building carrying a first aid kit crawled in. He was astonished to find the two women alive, thanks to automatic braking devices. "Thank God, the Navy's here," said the burned woman.

Firemen extinguished the flames in 40 minutes and began removing the bodies of 11 building occupants and the bomber's three-man crew. Early that afternoon, Brigadier General C.P. Kane, commanding general of the Atlantic Overseas Air Technical Service Command at Newark, arrived to take charge of the Army investigation.

He refused to take questions, or even give his name. A colonel accompanying him barked to the swarm of reporters: "The Army wants no publicity on this."

After 15 years of adversity, John Raskob [one of the building's original backers] was now hardened to it. He declared the building sound, and reopened it for business on Monday morning, two days after the accident.

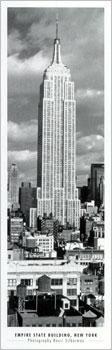

The spectacular crash — which seemed like a lost scene from King Kong — cemented the building's mystique as more than an office tower. The towering sentinel on New York's skyline had absorbed the blow, from a bomber no less, like a giant sequoia, quivering only momentarily.

Mitchell Pacelle reports on business for the Wall Street Journal. He won the New York Press Club's Business Reporting Award in 1999, was a finalist for UCLA's Gerald Loeb Award for Distinguished Business and Financial Journalism, and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

This article is excerpted from Empire: A Tale of Obsession, Betrayal, and the Battle for an American Icon, copyright © 2001, available from John Wiley & Sons, and this Sci-Fans links to Amazon.com.

More books about the Empire State Building or the World Trade Center

Back to Monstervision or Scifans

3000 names

See if your favorite person,

TV series or motion picture is

available: video/DVD/books