By William Thomas Sherman

James Quirk in Photoplay, August 1915

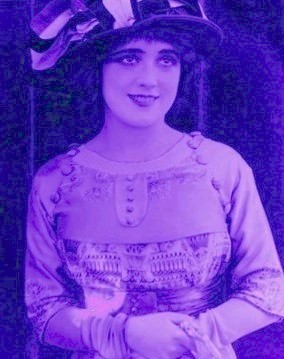

As well as being one of early film comedy’s most prominent and familiar personalities, Mabel Normand was also among its most creative explorers and innovators. In many ways she equaled, and in some respects exceeded, the work of her more famous male counterparts. Unfortunately, the subtlety, range and freshness of her brand of comedy has not infrequently been overlooked or made light of; and this, typically, due to the negative notoriety she has received as a result of persistent scandal.

Yet even taking the effect of scandal into account, we are left with the fact that the wide scope of her accomplishment cannot be adequately ascertained by screening a mere few of her films -- which is usually the most a given individual might see of her work. In a career that spanned from 1911 to 1927, she made at least 198 films: that is about 176 shorts and 22 features (four reels or more). During this same period she went through numerous vicissitudes and transformations: both negative and positive, some insignificant, some considerable. The negative changes were mostly a result of personal, as well as public, misfortunes in her life. Yet on the positive side she improved and developed as one would expect an intelligent and usually hard working artist to. The problem, however, was that the negative factors could seriously set back the progress she did make. For example, in the films of her last years she will at times seems devoid of much of that gaiety and quick instinct for irony which lent themselves to making her earlier outings so especially humorous and delightful. But this change came about in consequence of more than just ordinary maturation and development, and was, as well, the result of other factors affecting her, such as health problems, aforementioned scandal, and trends in the film industry.

The younger Mabel then is, generally speaking, noticeably more exuberant than the later one -- to say the least. So even though she progressed in her work, in a general sense there was, simultaneously, a gradual loss to her well-being stemming from external events largely beyond her control. It is the incidental life-affecting factors like these, some of them normal, some of them unusual, which have served to deprive film historians and enthusiasts a more just idea of her talent and ability. Since so much is varied in Mabel Normand’s story that brief assessments about her overall merit and scope as an artist rarely do her justice, and often need to be qualified. There’s simply so much that would seem to require explanation. To attempt now then, many years later, to properly evaluate her requires a bit more than the casual eye and terse reflection which silent film comedy is usually wont to receive.

In this the first of two essays, we will attempt a survey of her art and screen technique in that part of her career spanning from her first Vitagraph films in 1911, to her time at Biograph and Keystone, up until her last films made for Triangle-Keystone in 1916. A very good case could be made that this period from 1911 through 1916 was the high-point of her artistic energy and creativity. Be this as it may, it at least serves as convenient framework by which to demonstrate some of the sundry facets of her comic acting and technique. Although she did direct and write a few scripts for some of her own short comedies, it is as a performer that she stands out, and it is in this light that she is perhaps best viewed and considered.

At her tallest, Mabel was five foot in height, had thick brunette hair and expressive dark eyes. This is necessary to note because being very small and pretty gave her room to behave in ways that otherwise might not be so amusing if someone less attractive or sympathetic did those same things. In the way we might, even gladly, indulge a young child, a puppy or kitten for their somewhat unruly behavior because they are so naturally appealing, so “Mabel” (her comic character) could get away with things which others couldn’t and for similar reasons. The same behavior coming from someone else more full-grown or physically powerful, on the other hand, would probably be less funny, if not outright offensive. “Mabel,” on the other hand, while mischievous (and in rarer instances even obnoxious, see, for example, Mabel's Wilful Way 1915) never comes across as actually callous or mean spirited. On the contrary, time and again she displays an overt empathy toward her fellow players (in their character roles), and she would, as often as not, apologize to a fellow character after having pulled a prank on them, and with affection and sincerity mean it. If then she does act up or misbehaves, it’s rarely because her heart is in the wrong place.

She first acquired her earliest dramatic education from stage and club shows of various kinds she saw or heard about while growing up on Staten Island, including some presumably in which her father participated in as pianist. Otherwise, before entering films she was employed as an artist’s model in New York City, posing for well known advertising illustrators such as Charles Dana Gibson, James Montgomery Flagg, the Leydendecker brothers, Penrhyn Stanlaws, and C. Coles Phillips, not to mention a number of studio photographers as well. This kind of background certainly had an important impact on her subsequent film acting since modeling required her to assume all kinds of emotional attitudes, and postures. When an illustrator asked her to show longing, sadness, delight or gaiety that was just what she had to learn and give herself to do. It was then in no small part from the training provided by these modeling sessions that she began developing a quick and ready repertoire by which to successfully impart various feelings and emotions.

After receiving advice and suggestions from studio friends and acquaintances, Mabel moved from modeling into the just burgeoning movie business. It was 1911 and she was about eighteen years old when she was first hired at D. W. Griffith's Biograph Company located in Manhattan’s lower east side. Following this very brief, introductory stint, she went to work at the Vitagraph Company in Flatbush only to return to Biograph in late July 1911. She initially made some dramatic shorts with Biograph, some of these directed by D.W. Griffith himself. But ultimately, as events took their course, she ended up under Mack Sennett’s supervision as part of Biograph’s comedy unit. After that, sometime in the Spring of 1912, she, along with Ford Sterling and Henry Lehrman, accompanied Sennett in leaving Biograph to go West permanently to form the Keystone Film Company (a subsidiary of the New York Motion Picture Company based in New York City.)

Her earliest known surviving film is one from Vitagraph, Troublesome Secretaries, and it is with it we can start our survey. Based on that short and still photographs of others from the same company, we know Mabel’s Vitagraph films to have had a drawing room quality and a quaint, turn-of-the-century simplicity about them. One nice example of the latter is a scene from Secretaries where “Betty,” played by Mabel, is walked home along a residential lane by her boyfriend, Ralph Ince. As they stop their stroll, he warily looks about him before kissing her on the forehead. Betty, all this while, coyly giggles at his respectful caution and their mutual audacity. After waving good-bye to each other as they separate, she walks the rest of her way home with this curious look of concern on her face, like someone who, out of bashfulness, is not quite sure whether her romantic inclination has or might not get her into trouble.

“Betty,” a character Mabel often played in her Vitagraph comedies, was a young foil to John Bunny’s bumbling and struggling elder, and was in some ways the precursor to “Keystone Mabel.” Though different, they do share certain similarities. Both “Betty” and “Mabel” are playful and tend to a bit mischievous, as well as being attractive to men. The difference is that “Betty” is generally more submissive and subdued than “Mabel,” who is ordinarily more rambunctious and free spirited.

While replete with vitality in most of her earliest films, she appears more circumspect and demure (relatively speaking) in those made in the East. When, however, in the winter of 1911 she first went with the Biograph company on its annual winter-spring trip West, southern California, with its sunshine and orange groves, seems to have stirred in her a greater sense of freedom and independence such that she comes across as more self-assured and confident than previously. At first Mabel’s performances and mannerism were for the most part conventional and very much in keeping with D.W. Griffith’s school of acting, such as certain stock expressions used to convey various emotions and demeanors. Yet with time, she utilized and built upon this experience to develop and create styles and approaches of her own.

A number of Mabel’s Biograph films are dramas directed by Griffith, including Saved From Himself, A Squaw’s Love, The Eternal Mother, and The Mender of Nets,. Certainly, it is interesting to see what Griffith was able to bring out in her performances; and grave moments of tender sympathy or sadness, such as these films call for, are otherwise essentially absent in these early years of her career. Yet this observed, most of the films she appeared in at Biograph were not dramas, but rather farce-comedies, and these latter done under the direction of Mack Sennett.

The Biograph and Keystone comedies, as has been pointed out, had their conceptual origin in stage burlesque, newspaper comic strips, circus acts, and French film comedy – as well as not infrequently being in their way satires or takes offs on certain Biograph dramas. Moreover, the characters of these scenarios were usually intended as somewhat absurd caricatures rather than realistic personalities with the films being almost invariably ensemble pieces with little or no development permitted of individual characters.

Even though Mabel herself was a leading star in her Biograph and Keystone comedies, neither she nor any of Keystone's other players – or, for that matter, directors -- ever enjoyed much production control or say about how films were to be made. This was the result of tight management Sennett exercised over production; a factor which finally led to Chaplin and Arbuckle’s, not to mention Mabel’s, later departure from Keystone. These then are shorts with a few relatively big name stars, but no main star who had an independent say about the films content and how they were to be put together. It is true that around 1915 and 1916 that Arbuckle, both as star and director, was granted a certain autonomy, yet having to finally answer to Sennett still had a restrictive effect on his creativity and inventiveness while working with the company.

In an interview she did in the late twenties, Mabel described the “Fun Factory’s” cost conscious and assembly line production methods this way:

“So we, like other companies, would stop in the middle of one (film) and start another, simply rearranging the props, pulling a pair of overalls on over my frock, putting a cop's cap on Fatty Arbuckle, and having Ford Sterling or Charlie Chaplin chase us around in front of the camera.

“There’d be no script, no plot, no idea of what we'd do when we started -- and no title. All we needed was 600 or 700 feet of film showing us doing something and 300 or 400 feet of educational film to tack on it, such as how sheep are sheared or olives canned.”

While it is not true that all Keystone films were made without any written scenario or script, it is correct to say they were often as impromptu as planned out in nature. When written scenarios were used, they were frequently modified during the course of shooting, as well as in editing. It was not until 1915 and 1916, however, that advanced planning proper of individual films became possible. Yet despite the ad hoc planning and skimpy budgets, making these comedies day in and day out did require a not inconsiderable amount of toil and effort. When Chaplin returned to Hollywood to get his special Oscar in the seventies he visited with Minta Durfee and in chatting with her recalled what hard and regular work it was making those early films.

“Mabel was a comedienne, and he [Sennett] built everything around her. He would have worked her to death twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.”

~Minta Durfee quoted in The Keystone Krowd by Stuart Oderman, p. 115.

At Keystone, Mabel did direct a few short films herself, and did so competently, yet she never had pretensions to being a film making pioneer or genius. Nevertheless, she often did markedly influence those she worked with and was quite original and resourceful as an advisor and collaborator. In an article for Picture-Play, April 1916, Arbuckle, in answering how his films were put together, was quoted as saying “As we go along, fresh ideas pop out, and we all talk it over. I certainly have a clever crowd working with me. Mabel alone, is good for a dozen new suggestions in every picture.”

Mabel’s talent, however, lay in her being an imaginative screen performer, and less so a cinematic visionary -- as such. While one could cite a number of reasons, perhaps the best single explanation for her limiting herself is that she simply didn't possess the pride of great ambition to do more. Although she was naturally intelligent to the point of manifesting a kind of spontaneous and intuitive genius, her formal education was very limited and she did not have a manager like Charlotte Pickford to plan and organize her career and activities. In consequence of which, she appears to have been usually inclined to let others, and who she felt knew more, take the lead when it came to larger matters of production. On the other hand, however, it may very well have been (knowing what else we do know about her) that she did try and aspire to do more, but that the politics of business forbade it.

Her initial co-stars, both at Biograph and Keystone, were Del Henderson, Sennett, Fred Mace and Ford Sterling. Though Henderson was not part of the founding Keystone troupe, he did figure prominently in Mabel's early Biograph comedies. He usually, and without deviation, played a mild mannered, gentlemanly fellow. Sterling was featured more in her Keystone films than the ones made with Biograph. Mace and Sennett, on the other hand, were regulars in both the Biograph and early Keystone comedies. Following these, it was later Chaplin and Arbuckle who shared center stage with her. Other Biograph and Keystone stars who appeared prominently or frequently with her were Nick Cogley, Alice Davenport, Charles Avery, Al St. John and later Owen Moore. But it was the six first mentioned here -- Del Henderson, Fred Mace, Mack Sennett, Ford Sterling, Roscoe Arbuckle and Charlie Chaplin who most often served as her screen foil or partner.

The Roles

In the Biograph and Keystone films, Mabel played a relatively broad range of roles and types. To illustrate, the following is a list of some of them -- along with the names of a nominal few of the films in which those roles appeared. Naturally, it wasn’t unusual to combine a few of these in one film; for example, the spoiled daughter is also a flirt in What the Doctor Ordered and The Speed Kings.

To Continue...