The point of this website and the following paper is a discourse into the development of the depictions of homosexuals in the horror films from classic monsters to today as part of a projects for the class, Rhetoric of Popular Culture COMM 2360.

Greg Cortelyou

Rhetoric of Popular Culture

April 21, 2014

Dr. Stahl

Representations of Homosexuality in Horror Film

The horror genre reflects the anxieties and social tensions of the culture in which it is produced. As such, it reflects the struggles of the people within that culture. Homosexuals have historically been a fringe group, isolated and, in some cases, reviled. This makes them apt characters to place in horror films, to contrast the heterosexual, the monsters of horror may be homosexual, and to contrast the straight, the queer is presented. Yet, these depictions of homosexuals in horror film have evolved over time. From the inception of horror, these representations have been under constant flux and continue to change into today.

Benshoff finds homosexual interpretations in many classic monster movies in his book, “Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film.” Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde (1941) tells the story of a repressed man and his monstrous homosexual alter identity gaining control of his actions. This theme of repression is seen again in The Wolf Man (1941). The implication being that homosexuals like werewolves are unable to control the beast within, and even with the best defenses and safeguards, nature takes its course with disastrous consequences for the normalized, heterosexual public. Frankenstein (1931) chronicles the horrifying results of two men attempting to unnaturally procreate through science rather than a woman. The creation of new life also plays a role in Dracula (1931), as the makeup-covered, flamboyantly dressed Count Dracula preys upon men and women and, in some cases, turns them into vampires as well. This plays upon the fear of one devious homosexual manipulating others into his own perversion. In these contexts it becomes clear that homosexuality and horror films have developed beside each other since the inception of the genre itself. Horror at its most basic level shows audiences what they fear. Benshoff posits that three basic fears regarding homosexuals are primarily at work in horror films: that an acquaintance might be gay, that homosexuals will rape you, or that queer individuals will inevitably lead to the downfall of social institutions. Noting that “[t]he concepts “monster” and “homosexual” share many of the same semantic charges and arouse many of the same fears about sex and death,” Benshoff makes it clear that homosexuals and horror film have always been intimately linked. Unaccepted and largely reviled, homosexuals were forced into the same shadowy closets as the monsters of the silver screen.

Benshoff continues his critique into the 1950’s and 60’s. Known as an era of conformity and control, the country was coming to terms with the fact that homosexuality was more prevalent than anyone desired as well as the facts of life under the rule of McCarthyism. Also, Hollywood was coming under more strict scrutiny than ever before as censorship codes took hold. Homosexuality would retain its subtle role and monstrous tinge to avoid censorship. One film from this period was I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958), where a woman finds out her new husband is not quite what he seems to be. Also, I was a Teenage Frankenstein (1958) retells the horror classic through the doctor’s search for a beautiful face to give his muscular male creature so that he may blend into society. Benshoff argues that the subtext of these films gives highlights into America’s fears during the period. Anyone could be a communist. Anyone could be a homosexual. This ambiguity and fear drove the content of horror films during the period.

As censorship practices and codes lost their rigid hold on the production of cinema during the late 1960’s, particularly after the 1969 Stonewall riots, openly gay characters could be portrayed more freely. This of course particularly affected the horror movie industry because of its long use of homosexual subtext. Jeffery Weinstock illustrates this point with The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) in his book of the same name. While perhaps not a horror film in the classic sense, the cult classic draws upon many facets of the horror genre including Frankenstein’s monster, a mad scientist, vampirism, and dangerous alien invaders. Weinstock in particular elaborates upon the use of the myth of Frankenstein’s monster in the film, arguing that the replacement of the corpse man with a muscle man unveils the homoerotic subtexts of the original work. Dr.Frank’N’Furter also portrays the explicitly sexual vampire in flamboyant cape and pale make-up seducing Brad and Janet to his hedonistic ways. The Rocky Horror Picture Show played an important bridge from depicting homosexuals as monsters to being more frank about their representation. While these queer characters may not be admirable, they are also no longer executed for their homosexual transgressions. This reflects the American attitude toward homosexuality at the time. Gays and lesbians were gradually being de-regulated in a sense, a thing to be avoided rather than a thing to be destroyed.

Michael William Saunders’ work, “Imps of the Perverse”, takes a different approach to the ideas of homosexuality in horror film. Where Benshoff would highlight monsters as a metaphor for homosexuality, Saunders interprets homosexuals themselves as the monsters. For example, The Wounded Man (1983) follows a young man who discovers his homosexuality through an encounter with a street hustler. This encounter then grows into obsession and eventually murder to obtain the object of his desire. Again in Tom Kalin’s Swoon (1992), two Jewish, gay men commit several seemingly senseless crimes including a murder of a randomly chosen man. Their motivation is never fully explained as perhaps a metaphor for society’s lack of understanding of homosexuality in general. In the 1991 movie, The Silence of the Lambs, Buffalo Bill portrays the character of the murderous homosexual, an increasingly common trope. Monsters in this context lose their former mysticism given to them by the silver screen. Homosexual monsters were no longer depicted as monsters themselves, but as monstrous people, reflecting the growing understanding of homosexuality comparatively to the previous decades. Audiences began to see the sexually repressed wolf man and queerly-tinged vampire replaced with the more direct image of the homosexual killer.

These representations of gay men themselves being an increasing focus of horror comes particularly relevant during the AIDS outbreak. Saunders points to The Living End (1992) as a prime example. It follows the intersecting paths of two men recently diagnosed with AIDS. Throughout the course of the movie the protagonists are confronted with murderous lesbians, a wife seeking revenge for her husband’s homosexual infidelity, and a fag-bashing street gang. These crazed and near deadly encounters, while infused with a camp sensibility, instill a sense that “because both men are homosexual and HIV positive, the world around them has forced them to flee any received sense of what it means to live within the law” (Saunders 33). These diseased men find themselves in an equally diseased world. In this film homosexuality is violent and rough, but not in the classic sense which condemns homosexuals. In this instance, the horror of the film is directed as a call to arms of sorts to homosexuals and their allies, indicating that the only way positive change will be effected is through active resistance and possibly the extreme of violence. Saunders notes that the AIDS outbreak would go on to affect other horror movie genres particularly the vampire movie and zombie movie because of their focus on blood, disease, and transmission. These depictions of homosexuality reinforced the homophobic notions that gays and lesbians were sick both mentally and physically, and that they should be quarantined from society at large.

As the twentieth century turned into the twenty-first, this merging of homosexuality and horror has emerged as an entirely different animal, leading to the development of what scholar Claire Sisco King calls the genre of Queer Fear. Queer Fear differs from past horror movies with homosexual content because they are made specifically for a homosexual audience and generally by homosexual production teams and directors. Her article “Un-Queering Horror: Hellbent and the Policing of the ‘‘Gay Slasher””, uses the 2004 movie Hellbent to discuss the politics of Queer Fear. Proclaiming by its director, Paul Etheredge-Ouzts as “the first all gay slasher film,” Hellbent follows several gay characters on Halloween who are hunted down by a red leather clad muscle man called The Devil Daddy (King 249). King particularly examines the goals of the directors while making the film. Apparently, they didn’t want the homosexuals to be portrayed as stereotypical or extremely flamboyant, so they hired a mostly heterosexual cast for a movie dripping with homosexual imagery. The implication in this is that there are right and wrong ways to be a homosexual in 2000’s society. This is further supported by the fact that just as in many horror films, sex leads to death, especially when public or unsafe sex is involved. Hellbent, it seems, enforces multiple messages. While the very creation of such a film denotes acceptance and the growing homosexual market in American society, the plot dutifully punishes the flamboyant and the drag queens while sparing those who act more heterosexually. This reflects the mixed messages homosexuals receive about the proper way to act in society. Queer Fear is a genre still establishing itself and its messages that it will send to its audiences.

Depictions of homosexuality in horror film have been evolving since the inception of the horror genre. Each stage in development reflects the culture it was produced in, whether the heavily censored subtle subtext of early horror or the openly homosexual messages of 2000’s Queer Fear. The monsters of the shadow closets have stepped into the light. These representations will continue to evolve and change and show the tensions between the heterosexual mainstream and homosexual culture.

Works Referenced

Benshoff, Harry M. Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 1997. Book.

King, Claire Sisco. Un-Queering Horror: Hellbent and the Policing of the ‘‘Gay Slasher”. Western Journal of Communication. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. 2010. Journal.

Saunders, Micheal Williams. Imps of the Perverse: Gay Monsters in Film. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishing. 1998. Book.

Weinstock, Jeffery. The Rocky Horror Picture Show. London, England: Wallflower Press. 2007. Book.

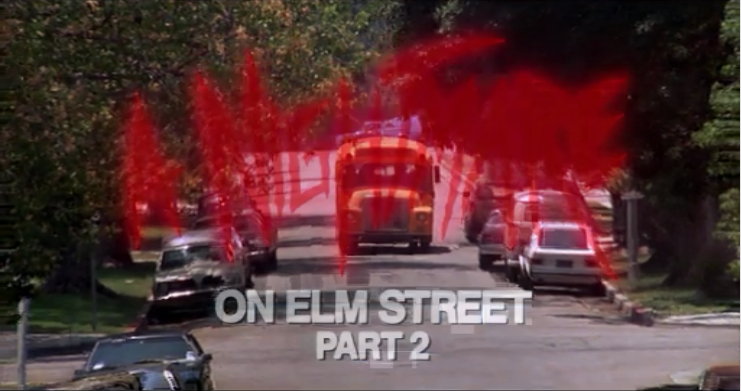

Creative Project

As I read more and more about my topic of homosexuality in horror films, I kept coming across a movie both scholars and critics describe as one of the most unintentionally homoerotic horror films of all time. Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddie’s Revenge tells the story of Jessie as the man of his dreams, Freddie Krueger, attempts to take control of his body for horrific ends. The monster of the film metaphorically serves to function as Jessie’s repressed homosexuality, transforming his teenage confusion into a maniacal killer. I decided to watch the film and offer my thoughts on key moments as the movie progresses.

Welcome to the gayest horror movie of all time.

Jessie wakes up covered in sweat after dreaming about Mr. Krueger. Perhaps an ill-conceived metaphor for a wet dream.

Wow. Nine minutes in and there's a bare butt. This movie is moving faster than some pornos do.

In the locker room, a common set for this movie, Jessie's friend tells him that the coach is a homosexual who is into S&M, which is what inspires him to be so cruel.

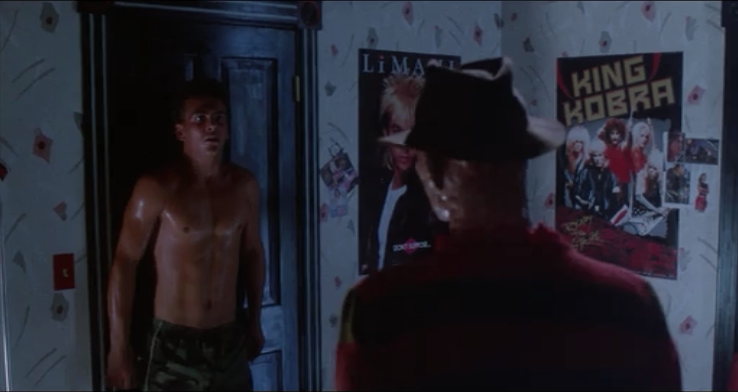

During Jessie's first confrontation with Krueger, Krueger tells him "I need you, Jessie," and of course, whether intentional or not, the still speaks for itself.

Cleaning his room turns into a dance number where he rubs his pop gun to the tune of Fonda Rae's "All Night Long"

When his mother and love interest enter the room, notice the sign in the back proclaiming "NO CHICKS"

During a nightmare, we see Jessie has been reading Jack Kerouac's On the Road, a book nearly banned for it's discussion of drugs and homosexual behavior.

When Jessie can't sleep one night, he walks in his pajamas to the local gay bar.

Uh oh, turns out this is a bar Jessie's leather-clad PE teacher frequents.

When coach takes him back to the school to instill some discipline into him via strenuous exercise, the coach is suddenly attacked by balls flying off the shelves.

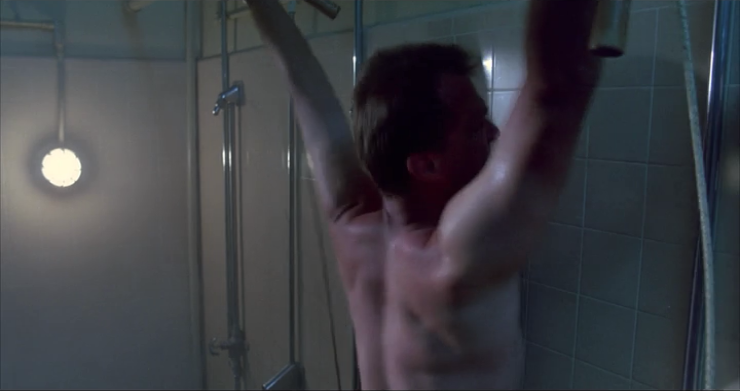

Tied up in the shower by mysterious forces, the coach is then

whipped with towels before being killed. The S&M character killed by whipping is somewhat ironic.

Victim #1

Later, during Jessie's sexual encounter with his girlfriend, Freddie (perhaps manifesting Jessie's homosexual desires) takes over Jessie's body to quickly end the rendezvous.

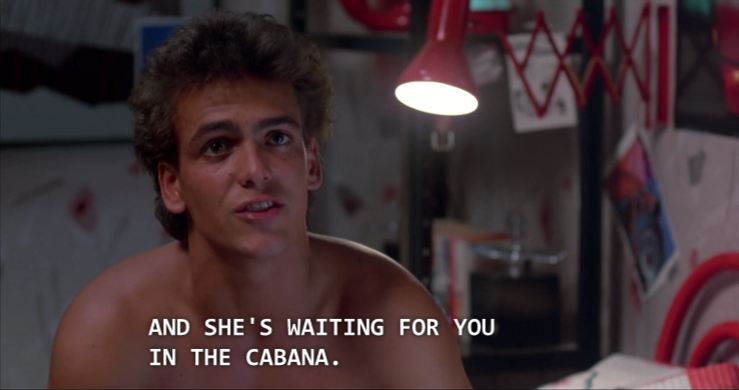

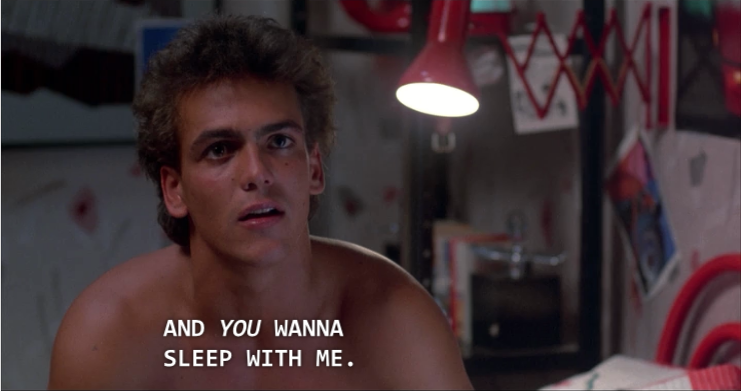

Jessie flees to his friend, Grady, for some help.

This selection of dialogue pretty much speaks for itself. Were the writers ignorant of the implications of their words or was this intentional?

Grady, of course, winds up as Freddy's next target, and, of course, meets his end while scantily clad, just as the coach.

Victim #2

Meanwhile, at the party, we see things have devolved into large groups of normalized couples.

Welcome to Heteroland!

Again, writers. Consider your word choice, please.

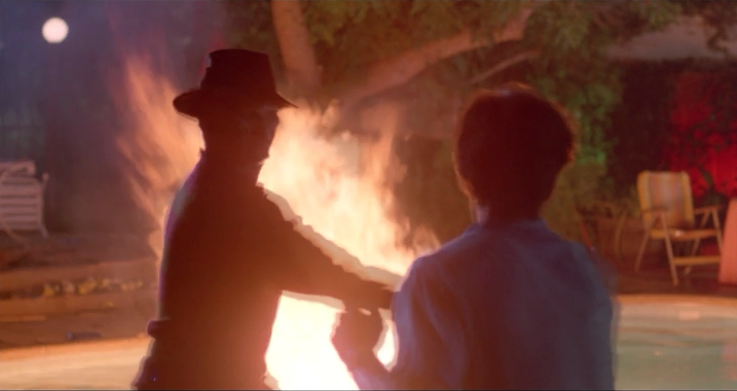

The monster of homosexual desire showing up in Heteroland causes quite the disturbance.

Victim #3. Noticing a pattern yet?

High on the heels of #3. The fourth and final death of the movie is also a young, attractive boy.

The girlfriend then goes to confront the monster.

By proclaiming her love for Jessie, she has managed to free him from the homosexual monster.

Or maybe not...

Frankly, after watching this film, I have concluded that the excessive hodgepodge of homosexual subtext cannot be completely unintentional. Nightmare on Elm Street 2 overtly displays the anxieties of homosexual teenagers such as fear of isolation from family, troubles at school, dealing with attractions to friends and teachers, and telling the girl that she’s not right for you, then packages them up as a horror movie. Freddy functions as a monster born of Jessie’s repressed homosexual urges, and although the monster is banished by traditional heterosexual love, the very last moments of the film show that it is only a temporary victory. Jessie’s urges will never go away, and in this way, the monster continues to live on. I went into this movie thinking what I had heard was largely reading into the subtext of the movie, but after watching it I don’t see how anyone couldn’t see the overt messages about teenage homosexuality. Even the poster tagline for the movie proclaims "the man of your dreams is back."