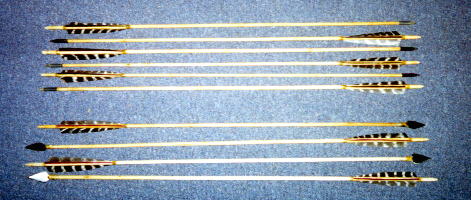

Archeryrob's Arrows

I make my own arrows from saplings and the correct size branches. I use Southern Arrowwood as that grows naturally here in Maryland. Southern Arrowwood is also known as "Arrowwood", "Arrowwood Viburnum" and "Viburnum dentatum L". It received the name from Colonists because it was used by American Indians for arrow shafting. It would be classified as a shrub or small tree usually growing about 3' -10' and usually never thicker than 1 1/4" at the base of the tree. The tree seems to prefer or just grow better in wet to moist soils and I sometimes find it making thickets near small streams or swampy areas. As the tree grows it starts to lean over and sometimes as it grows larger even leans over to touch the ground. This make identification easier when traveling through the woods. The leaves of the tree are round with saw tooth edges and come to a point on the tips and can vary in size even on the same tree. Leaves are a dull medium green on top and are a pale green underneath with small hairs. The natural range of this tree is from parts of Maine, west to Indiana, south to Louisiana and Southern Georgia. One other way you can help identify this tree is when the bark is removed it produces a smell similar to melon sometimes but never the real green smell some plants have. The best book I have found to help you find Southern Arrowwood is "National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees" eastern region.

Southern Arrowwood Leaves

Picture from:

"National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees" Eastern Region

The raw shafts can be gathered anytime of year, but like any other woods, it does much better when gathered when the sap is down. They still can be gathered in the summer, but some will be lost to splitting at the ends or near small knots. I personally like to cut my raw shafts about 36" - 40" to allow for splitting and not being able to straighten to close to the ends. The fresh young sprouts of the correct size can be gathered or the branches of larger trees can be gathered for shafting. The straightness is not as big an issue as whether there are any imperfections in the wood such as: deer or locust damage causing wood to grow irregular, large knots, close 'S' bend in the wood making straightening impossible, and very sudden bends. All slow gradual bends can be removed and you will spend less time straightening shafts than laboring through the woods looking for that perfect shaft, of which, I have not yet found.

After shafts have been gathered the shafts and seasoned them with the bark on to try to prevent splitting. The shafts will need to be dried for at least 2 weeks with the bark off and maybe a month with the bark on. The longer you season has not seemed to make much difference to me along as they are dry.

There are two ways to straighten shafts. The first is to work them every day as they dry. You need to eye straighten them by hand every day and bind them back up together until they are dry. When they are dry they will stay straight or as they have dried. Some books about Indians making arrows talked about bundling arrows and hanging them to dry in the tipi for 6 months. I have tried bundling shafts and hanging them to dry. As the shafts dry and lose their water the shrink in diameter which means they are not bundled tight any more and can reform to their former crooked ways. They must be taken down and restraightened every day as they dry and rebundled until the next day. Some will not be entirely straight and will need some heat straightening to finish them.

To start the second way you can start to straighten shafts after they are dry. I use bacon grease and a candle flame to apply the heat. The grease helps to prevent scorching and the grease soaks into the wood during this process as moisture protection. Heating the wood for too long a time in one spot will cook the wood and make it brittle. Flex all scorched spots to see if it will break. You just need to apply the flame to the area you wish to bend just like you would on a bow and when the wood feels like it will burn you it is ready to bend. Bending the wood can be accomplished with hands, over your knee or with an arrow wrench. The latter is which I prefer as I can create a better hinge point, but I do use my hands to bend out long gradual bends. Once you have your shaft straight or very close to being straight you should leave them sit for about two weeks to adjust to the natural stresses in them and the new ones you have applied to them. Then after the two weeks, go back and straighten any that have readjusted. Now they should stay straight, but remember to always recheck them, they could need touching up straightening from time to time. Remember that primitive shafts like these are not run on a doweling machine and will never be perfectly straight, but should look straight as you look down the arrow.

I use a piece of Cedar for an arrow wrench. The wrench has a hole carved through it to be about 45 degrees. The edges are rounded as to not make and hard bends on the wood as it is bent. The wrench can be made from anything that you wish to carve into.

Cedar Arrow Wrench

Arrow Tools

Once all shafts are straight ,then they need to be the correct size. I use a thumb plane and my work bench to reduce the shafting to the correct size. I use my spine tester to tell me when I have the correct size. The shaft will look a little octangular when complete but sand paper will round it nicely with out reducing the spine more.

Then I carve the self nocks and cut them to length. Self nocks should be wrapped with sinew just in front of the nock if they are cut to clamp the arrow like modern glue on knocks. This clamp style nock or just tight fitting nock puts stress on the wood in the natural direction that would be used to split an arrow. I have made them without the sinew wrap and they split every time. When you take several hours to make one arrow you will go to any length to preserve them.

Primitive Fletching

Feathers and broadheads are applied with hide glue and sinew. The broadhead are glued in with hide glue. Then sinew is wrapped around the point to secure it and sinew wrapped behind the point on the shafts to prevent splitting on hard contact with bone or other hard materials. Then it all is sealed with hide glue. I start fletching by gluing the feathers down in the back and working to the front as the hide glue cools and sets up enough to hold it in place. The hide glue sets up fast as it cools and sets up best as it dries. After they are glued down I wrap both ends of the feather with sinew to add protection to the end to keep them from peeling up and coat the sinew with hide glue for extra strength. If they need to be waterproof, then use Pine pitch as sinew sealant. I am experimenting with trying to use Pine pitch to glue down the feathers but it sets up too fast. I am questioning other knowledgeable people about ideas to use pitch as fletching glue and will report back when I get it too work properly.

Southern Arrowwood Arrows

Other Trials of Materials

I have used Multiflora rose for shafting and found them to work. They straighten very well as green shoots if kept up to everyday but, they would not heat straighten very well at all. They also split easy when the arrow contacted a hard surface when shot thin end first. I tried this shafting because I thought it would be similar to Wild Rose. It's readily availability and green straightening was a plus but, it's not taking heat straightening and weak tips made me give up on this shafting. I am reworking using it with the thick end forward and will see how it does.

I have also split and plained out arrows from Black Locust and found it to be an extraordinary amount of work. The lack of a straight grain made wood planks very large and consumed a large amount of time with a thumb plane to reduce to shafting. The shaft I made was fairly heavy and should have had good penetration. I never finished the arrow because I wanted a set to shoot to get used too. I have thought about changing this approach to Poplar or White Oak. I have read that Poplar was not very desirable but it is very straight grained and would split good. I may cut some White Oak this year and try arrow shafts from them. I am not worried about the heavy weight and distance as I do not shoot very far.

I am trying all kinds of arrow material for primitive shafts. I am very interested in the materials that you are using. I am gathering information for myself and The Bowyers Den web page. If you have any different experience than I have listed here I want to hear from you. Please use one of my e-mails on the main page and we can talk for a while.