Unfortunately, much of the organic architecture produced in the 60s and 70s was a dismal failure, this because many of its proponents and practitioners were pop-artists without any engineering or architectual skills and who treated the hand formed concrete merely as a sculpting medium. They were more concerned with the novel forms they were creating than they were with their practicality as a habitat. Concrete is far from an ideal building material because it is impervious. Without adequate ventilation, insulation, and humidity control it can produce uncomfortable and quite toxic indoor environments. Poorly made, it can deteriorate rapidly under the elements. Without an understanding of its physical properties it can easily fool the ignorant into attempting structures which are dangerous. Thus it's no surprise that very few of these ill-conceived dwelllings exist today and that in some countries, America in particular, the entire architectural concept has developed a bad reputation. Indeed, many architecture students are never exposed to this form and many experienced architects remain completely ingroant of it. But a small number of designers and architects with a clear grasp of what the materials technology was and was not capable of and with a much more sophisticated understanding of the concept, have perpetuated the organic architecture movement, often giving their work new names in order to avoid the stigma created by the early failures. Of these people perhaps the most sophisticated of all are the brothers Roger and Martyn Dean.

The Deans are known mostly for their work producing album covers and stage set designs for the rock groups Yes and Asia but the pair have extensive design experience with everything from art, fantasy, and science fiction books to appliances to architecture. Their designs are heavily inspired by Art Nouveau, though often with a very futuristic slant.

Roger Dean`s interest in architecture sprang from its increasing importance, if not dominance, in his fantasy artwork. Like the early visions of Finsterlin, his imagined architecture was simply part of his Art Nouveau inspired scenery but over time developed an increasing sophistication and complexity. In designing a building as part of a fantasy background for a rock album cover, he could work out the complete design details of the whole structure, including details which would never appear in the finished paintings.

The two brothers began their realization of what they refer to as 'tectonic' architecture as a result of a seemingly simple design project begun by Martyn in the late 70s called the Personal Retreat Pod. The Pod was a precursor to the immersive VR pods now being developed today for public entertainment purposes. It was intended to be a kind of relaxation appliance, a tiny personal retreat equipped with entertainment and environment control equipment which the user would climb into in order to rest or meditate in complete isolation from the noisy environment outside. The actual design of the Pod engaged the two brothers' efforts for many years as they refined its ergonomics and fabrication, Roger Dean taking the role primarily of designer and Martyn the role of engineer.

[Dean Retreat Pod]

The work on the Pod later led Roger Dean to the design of a novel kind of childrens bed based on a mushroom-shaped chamber which combined room and bed into one. In studying its ergonomics and interviewing as many different people as he could about how the look and feel of the bedroom effected them, he realized that he had clued-in to something powerful. He noted that there was a kind of subconscious, primal, uneasiness in people created by the structure of their environment, the shapes of rooms and buildings around them. Children, unshielded by the in-grained rationalizations of adulthood, express this unease fairly directly. They are suspicious of dark spaces that are out of their sight and imagine them inhabited by a variety of horrors. Children cry out at night in fear of monsters under their bed or inside closets. When frightened, they cacoon themselves under blankets, as if the bedroom itself were too large a space to feel safe in without light to make sure that the contents of every corner is suitably exposed.

[Dean childrens bed]

Adults express this same unease in subtler ways. A bedroom may be uncomfortable to sleep in unless decorated in a particular way or with furniture in a certain position. We fill the space under beds with storage boxes, close it off with platform beds, or get beds with built-in drawers. We disguise closets with mirrors or sliding doors that make them seem more integral to the wall or we put doors on them with louvres, subconsciously making it harder for whatever might hide there to remain unheard. Many modern homes have done-away with the bedroom closet altogether, replacing it with separate dressing rooms. We instinctively arrange our furniture so that every chair has its back against a wall if possible. We fill the chronically problematical corners of the room with decorative items, rarely used chairs, or shelving to fill them up. Sometimes there is never a right place for a piece of furniture. We constantly trip over or knock into things whose placement has always been the same and for which there may be no other logical locations and yet the locations are still wrong, still in our way. Rooms whose designed function just doesn't meet our needs or the flow of traffic in the home get used in inappropriate ways. Kitchens become main entrances, dining rooms become offices, garages become warehouses and workshops. Sometimes we have no means to respond to the unease created by our environment. We cannot adequately express or explain it, may not consciously even be aware of it, and so it manifests as signs of stress, restless sleep, unexplained irritability.

In studying this Roger Dean began to realize that our architecture was ergonomically flawed, out of synch with the way our minds and bodies worked. We are animals with a spherical sense of perception defined by the spherical radii of arm's reach and sight and yet the environment we construct is rectilinear. We are the proverbial round pegs in square holes of our own creation. And so building upon the work from this childrens bedroom he began to develop a more ergonomic approach to architecture influenced, of course, by his own artistic tastes and which evolved forms similar to those of the earlier free-form organic architects as well as, naturally enough, the instinctively chosen forms of Primary Architecture.

[early Roger Dean design detailing construction. First stage is site excavation and slab foundation installation. Next, inflation of balloon forms for rooms. Next, Gunnite is sprayed onto forms and, when set, interior details sculpted. Final, backfill to below-grade portions, addition of surface treatments to cover utilities conduits, and removal of forms]

[floor plan for above structure - left-to-right; below-grade

floor, ground floor and entrance, top floor]

[floor plan for above structure - left-to-right; below-grade

floor, ground floor and entrance, top floor]

[concept for Virgin Records building by Roger Dean]

[concept for children`s playground by Roger Dean]

[hotel bungalo suite concept by Roger Dean developed for Brighton Marina development project UK, later used for International Ideal Home Exhibition, Birmingham UK 1981]

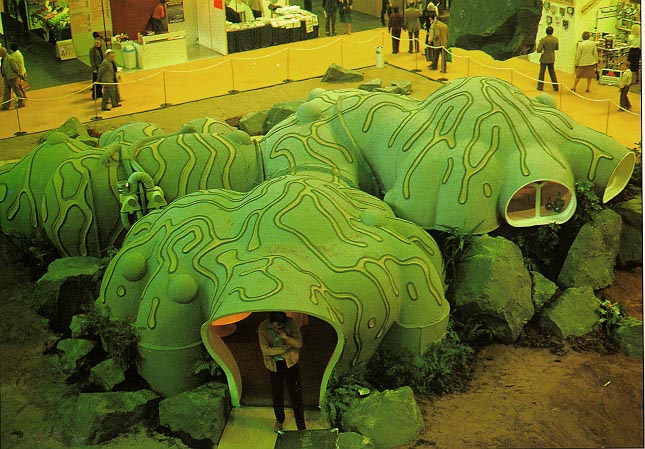

[fiberglass prototype of Brighton Marina suite built for IIH Expo]

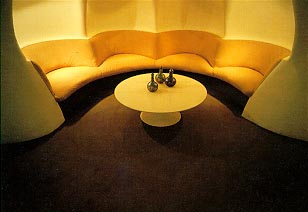

[interior views of Brighton Marina suite]

[concepts for theme park development mid 80s by Roger Dean]

[concept for Sudbud complex, Darling Harbor, Sydney by Roger Dean. Intended to be completed for Australia`s bicentenary celebration but as yet uncompleted]

The Deans' tectonic architecture is superficially similar to other organic architecture but differs in some fundemental ways. Their use of non-Euclidean forms is not decorative and their structures are not meant to emulate animal shapes. They are intended to be ergonomically optimal, the non-Euclidean shapes chosen for the same reasons they are chosen for the designs of modern automobile dash boards or the shapes of ultra-modern appliances. Their homes are designed from the inside-out, the whole structure formed by the shape, size, and placement of individual rooms rather than having a uniform whole structure that is afterward compartmentalized into rooms. Each room is a self-contained unit, naturally spherical or spheroid in form and with its interior features, its furnishings and fixtures, sculpted into the walls, floors, and ceilings. Free-standing furniture is largely redundant and even obstructive to these designs. The rooms are then clustered together in groups of related function, sometimes merging together or hierarchically ordered, and the groups of spaces are massed and merged together as though the entire structure were a single, seamless, monollithic whole. Roger Dean avoids the use of doors, preferring complex arrangements of rooms where the locations of curving walls and pocket-like room entrances provide for necessary privacy without the sense of clostiphobia created by doors.

With his artistic roots in Art Nouveau, Roger Dean favors ornamentation but not in the manner typical of conventional architecture. His ornamentation is integral to the surface of the structure. Decorative moldings around windows and doorways, surface textures on roof areas, interesting portals and molded-in alcoves. He is keen on the use of color, particularly stylized color patterns reminiscent of those on wild animals, sea creatures, and exotic plants. Some of his designs are fantasy inspired, their exteriors made reminiscent of alien versions of Asian temples, Arabian minarettes, or the traditional English thatched roof cottage. Others are inspired more by nature, designed to look like giant fungi, coral reefs, stellagtites, the smooth surfaced rocks and mesas of the desert, or the hanging nests of weaver birds. These designs represent some of the most beautiful architecture ever imagined.

Though complex in form, the Deans' tectonic architecture is incredibly simple in structure. Their designs are primarily rigid monolithic shells which rely entirely on the strength of that shell material, an approach common among the organic designs of the 60s and 70s. Gunnite, a sprayable concrete, is the primary building material for the Deans' structures but they have also used fiberglass to prototype their designs and a variety of other materials are possible-anything with the needed structural strength that can be sprayed onto forms. The construction technique is simple and relies on the use of inflatable forms for the individual rooms in a system similar to the Monolithic Domes construction method but based on fiber reinforcement rather than welded rebar. A system of segmented fiberglass forms is also used. The forms are removed when the gunnite is still not fully set yet able to support the structure so that hand finishing can be done to smooth off the marks of seams, to mold stairs and similar features with small scale molds, and to hand-sculpt the very small detail items. The designs use an external infrastructure where electrical cables, ventilation ducts, and the like are mounted outside the room shells and covered in conformal housings and additional sprayed-on materials or hidden under secondary roofing structures. The approach lends itself to modular construction since the forms of common features, such as window wells and small rooms, can be duplicated for use throughout one structure or a series of structures. This is very diffierent from other forms of organic architecture where everything is hand-made and unique. Such modularity is important in the Deans' designs because of the precision of the ergonomic engineering employed. Though seemingly fluid and capricious in form, these structures are as fine tuned as the cockpit of a fighter aircraft.

Another approach used by the Deans to adapt the interiors of existing rectilinear structures is to employ fiberglass, fabric, and foam composites to form an organic interior landscape almost like a form of soft-sculpture. This approach grew from their work on stage set desigs and in the interior design of night-clubs. The technique involves designing an interior space much as with the rigid shell materials but within the confines of the rectilinear boundaries of the existing structure then executing it in foam filling in and concealing the square corners. It's almost as though the structure were entirely filled with foam and then the new spaces carved out. The foam is then covered with a variety of sewn fabrics. Seating spaces and tables are created from the base foam material as foam composites using foams of different density and hard rigid materials for support or hard working surfaces. The approach is not as efficient as the rigid shell techniques due to the volumetric losses from the original rectilinear structure but can be readily combined with the rigid shell approach.

[design for interior of London nightclub by Roger Dean]

[coral head foam lounge design by Roger Dean]

[free-form organic interior system based on fabric covered multi-density foam structures - Roger Dean]

Strangely, very little of the Deans' novel and elegant architecture has seen the light of day. Many grand projects such as a building for Virgin Records, resort communities in the UK and Australia, and more have been planned only to be left unrealized when sponsors bailed out just as construction was about to start. It's as though the fascination and excitement inspired in by these designs is countered at some point by a reluctance to follow-through with such unconventional buildings. As if to realize these structures is to somehow challenge everything we know about the concepts of home and place, perhaps risking some form of retaliation from a civlization not quite ready to face the future, only to give it lip service.