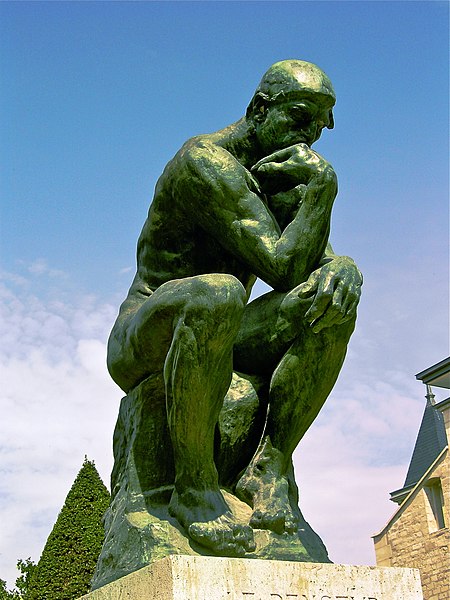

I'd like to put three hypothetical questions to my readers. They might sound rather silly, but as we'll see, they have profound implications for the very concept of what it means to be human. Let us assume that the very first creatures on Earth who possessed a natural capacity to reason - i.e. the first people - had primate parents who lacked this capacity. Let us also assume for argument's sake that there were only two people in the beginning - Adam and Eve - who later went on to have several children. Adam and Eve's parents were therefore non-rational animals. Here are my three questions:

(1) Would it have been possible for Adam to have had an identical twin brother, Brad, who was physically identical to him, but who lacked the capacity for rational thought?

(2) Would it have been morally wrong for Adam's eldest son, Cain, to start a family with Brad's lovely daughter, Diana, who (like her father) lacked the capacity for rational thought, instead of starting a family with his younger sister Flora, the only other female of his generation who possessed the capacity to reason?

(3) If Cain had had intercourse with Diana, would this have constituted bestiality on his part?

Associate Professor Kenneth Kemp is the author of a recent article on Adam and Eve, entitled, Science, Theology and Monogenesis (American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, 2011, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 217-236). The article has attracted quite a bit of online discussion, both pro and con, garnering a positive review from a Thomist philosopher, Associate Professor Edward Feser (Monkey in your soul, 12 September 2011 and also Modern Biology and Original Sin, Part I) and a thumbs-down from an atheist mathematician and Science Blogs contributor, Associate Professor Jason Rosenhouse (see here and here). Professor Kemp's paper was written with the intention of harmonizing science and theology on a point where they seem to conflict: according to recent scientific findings, the human race sprang from a stock of no less than 5,000 hominid progenitors, whereas Judeo-Christian theology has traditionally taught that we are descended from just two people: Adam and Eve. (Note: the current technical term for human beings and their immediate ancestors is not "hominid" but "hominin". However, I shall defer to popular usage in this post.) Kemp's proposed solution is that the human race is descended from only two people with rational souls (Adam and Eve), in addition to several thousand individuals who were biologically human - i.e. of the same species as Adam and Eve - but who lacked the capacity for rational thought, since they did not possess spiritual souls. Thus Kemp attempts to combine theological monogenism - the belief that we are descended from a single pair of individuals who were rational and in communion with God - with biological polygenism, which says that the human stock never numbered less than about 5,000 individuals at any stage in its history. Kemp proposes that Adam and Eve's descendants continued to inter-breed with their sub-rational animal contemporaries for an extended period of time, and he suggests that any offspring resulting from matings between sub-rational hominids and people with spiritual souls were automatically endowed with a spiritual soul by God. Because rationality confers a biological advantage, Kemp argues that humans with a rational soul would have completely supplanted sub-rational individuals within the hominid population after about 300 years or so.

So how would Professor Kemp answer my three hypothetical questions? If I read him aright, the answers that he would give are as follows:

(1) Yes - as Kemp puts it in his article, "God did not owe Adam and Eve's cousins a rational and therefore immortal soul" (p. 233), and he adds that the same principle would have applied to "their siblings" as well;

(2) Yes - for as Professor Kemp rightly points out, "the relationship between the individual mates would be incapable of having any personal dimension" (p. 232); and

(3) No - because in Kemp's opinion, "The sin involved would be more like promiscuity - impersonal sexual acts - than like bestiality" (p. 232).

In this essay, I shall argue, contra Kemp, that the answer to question (1) is "No", which means that questions (2) and (3) are completely irrelevant.

From an Intelligent Design perspective, it does not matter how many progenitors the human race had. However, in the next three posts, I will be arguing that Professor Kemp's attempted reconciliation of science and theology suffers from philosophical, scientific and theological flaws. I would like to acknowledge at the outset that Professor Kemp's synthesis is a bold one, and I have the greatest respect for his academic integrity, even though I also believe that the solution he puts forward is an unsatisfactory one.

In this post, I will be arguing that Professor Kemp's attempted harmonization of scientific polygenism and theological monogenism comes at a terrible price: he achieves his goal only by rending asunder the seamless concept of humanity. According to Kemp, there are no less than three distinct concepts of humanity: biological (belonging to the human species, genetically speaking: i.e. being able to readily inter-breed with people), philosophical (having an ability to reason) and theological (having the opportunity to be in a state of eternal friendship with God). The third is a subset of the second, which is a subset of the first; hence every rational human being is a genetically human animal, but not vice versa. (Actually, Kemp is not sure whether the second and third groups coincide, but he insists that the second group is smaller than the first. Thus he believes that not all genetically human animals are naturally capable of reasoning; only those genetically human animals that have been endowed with spiritual souls possess this capacity.) I will argue below that Kemp is committing a major philosophical error here. I recognize only one concept of humanity, and I shall argue that of necessity, anything which is biologically human also possesses a rational nature (and hence, a spiritual soul).

In my opinion, Kemp's three-way fragmentation of the concept of humanity is philosophically flawed on several counts.

First, it would render meaningless the traditional philosophical question: "What is man?" Kemp would have to reply: "Which kind of man are you talking about – biological man, philosophical man or theological man?" In his paper, Kemp even distinguishes between three species of man: "biological man" (a population of inter-breeding individuals having the same kind of body that we have), "rational man" (a species whose members all belong to the species "biological man", but also possess spiritual souls, with a capacity to reason), and "theological man" (a species whose members are all rational human beings, and who have also been offered eternal friendship with God). Kemp can tell me what biological man is, and philosophical man and theological man as well; but he cannot tell me what man is. Kemp evidently considers himself a philosophical disciple of St. Thomas Aquinas. I'm not so sure that Aquinas would agree. For Aquinas, unlike Kemp, can tell us what man is: he tells us that "the proper operation of man as man is to understand; because he thereby surpasses all other animals" (Summa Theologica I, q. 76 art. 1), and in the same passage, he adds:

[T]he difference which constitutes man is "rational," which is applied to man on account of his intellectual principle. Therefore the intellectual principle is the form of man.

This brings me to my second objection: Kemp's fragmentation of the concept of humanity would make it impossible to affirm the statement: "Man is a rational animal," which Aquinas (following Aristotle) understood as a proper definition of what it is to be human. On Kemp's account, this statement becomes either false or trivial. It is false when applied to biological man, for it is not true (according to Kemp) to say that having a body like ours is a sufficient condition for having a rational, spiritual soul. And it is trivial when applied to philosophical man, for then all it says is: "Every human being possessing a rational soul is rational." In either case, the sentence, "Man is a rational animal," fails to say anything genuinely informative.

My third objection to Kemp's fragmentation of the concept of humanity is that it lends itself very readily to a false anthropology, in which our rationality (which we possess by virtue of being endowed by God with spiritual souls) is envisaged as something which is added onto our animality (which we possess simply by virtue of being "biologically human"). According to this false anthropology, every human person is an animal plus a rational agent. It is as if we had two souls: an animal soul which handles bodily functions and has various sensory capacities and appetites, and an immaterial soul which thinks and chooses. Let me hasten to add that Professor Kemp does not subscribe to this flawed anthropology; however, the distinction he draws between what he calls "biological man" and "philosophical man" certainly seems to invite that way of thinking about man. Such a conception of man is radically mistaken, as The Catholic Encyclopedia points out in its article on Man:

According to the common definition of the School, Man is a rational animal. This signifies no more than that, in the system of classification and definition shown in the Arbor Porphyriana, man is a substance, corporeal, living, sentient, and rational. It is a logical definition, having reference to a metaphysical entity. It has been said that man's animality is distinct in nature from his rationality, though they are inseparably joined, during life, in one common personality. "Animality" is an abstraction as is "rationality". As such, neither has any substantial existence of its own. To be exact we should have to write: "Man's animality is rational"; for his "rationality" is certainly not something superadded to his "animality". Man is one in essence. (Bold emphasis mine - VJT.)

Our rationality is part of our human biology, not something separate from it. Or as Fr. John O'Callaghan puts it in his perspicuous essay, From Augustine's Mind to Aquinas' Soul:

...Aquinas is effectively eliminating any suggestion that to be human is to be anything other than an animal whose form of life is rational. So the duality manifest in the definition rational animal does not correspond to a duality in the thing defined. On the contrary, the unity of the two elements of the definition corresponds to the absolute unity of the form of human life. The unity of intellect and will is not preserved in a special power that separates man from animals. Rather it is preserved in the unity of the soul that unites man to animals, insofar as it specifies the form that animal life takes in being human. (Bold emphases mine – VJT.)

To be a human being, then, is to be an animal whose form of life is rational. But according to Professor Kemp, our animality is something which is separable from - and at times actually separate from - our rationality: for according to him, the original population of 5,000 hominids consisted of animals who were of the same biological species as Adam and Eve (i.e. biologically human animals), but who lacked rationality. There is thus a real distinction between human animals and rational animals! By now, it should be readily apparent to readers that this proposal is totally alien to the thinking of St. Thomas Aquinas, whom Kemp quotes in his article to bolster his case.

I should add that Professor Kemp's terminology at times inconsistent: thus he refers to Adam's hominid ancestors as "biologically human" (p. 232), but he also says that "Only beings with rational souls (with or without the preternatural gifts) are truly human" (p. 232). I'm sorry, but that makes no grammatical sense. If I'm a happily married man, then I’m a married man; likewise, if I'm a biologically human being, then I'm a human being. It's as simple as that.

It is also puzzling that on page 232 of his article, Professor Kemp refers to Adam's ancestors and relatives who lacked a rational spiritual soul as "genetically human-like" (which is unobjectionable), but also as "biologically human" (italics mine). Well, which is it? Human or human-like? You can't have it both ways.

Kemp also discusses an article by Andrew Alexander, C.J., entitled "Human Origins and Genetics" (Clergy Review 49, 1964), which makes a somewhat different proposal to the one Kemp is making. According to Alexander, Adam and Eve belonged to a larger population of hominids, but unlike the others, they both possessed a final crucial mutation, which crossed a philosophically or theologically critical threshold. Unfortunately, in my view, Alexander spoiled his account by going on to say that this mutation did not establish biological barriers to reproduction, i.e., did not give rise to a new biological species. If he had proposed a mutation that created a barrier to reproduction, making it very unlikely that Adam and Eve would interbreed with their companions, but not impossible for them to do so, then it could have been truly said that they would have been the only biologically human animals in the original population of hominids, in addition to being the only rational animals in the group. Personally, I would have no problem with such a proposal, from a philosophical perspective, although I shall argue in my final post on Kemp's article that even this modified proposal is extremely difficult to square with Scripture and the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Professor Kemp's misreading of Aquinas constitutes a very powerful fourth reason to reject his proposed fragmentation of the concept of humanity. Incredibly, Professor Kemp argues that his distinction between biological humanity and philosophical (or rational) humanity is fully in keeping with the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), who taught that while a certain kind of body is necessary for rational activity, reasoning itself is not the act of any bodily organ; rather, it is an incorporeal operation performed by the human soul, apart from the body (Summa Theologica I, q. 75 art. 2). Aquinas also taught that because the human soul is capable of performing some actions (e.g. reasoning) without the body, it is impossible to generate a human soul simply by making a being with a human body. Instead, the human soul can only come into being as a result of a special creative act of God (Summa Theologica I, q. 90 art. 2).

Quite so; but Aquinas also taught that the human soul is essentially the form of the human body (Summa Theologica I, q. 76 art. 1); which means that nothing can be said to have a human body unless it also possesses a human soul. The ecumenical Council of Vienne (1311-1312), which was convened a few decades after Aquinas' death, took the same view, for it declared in no uncertain terms: "[W]e define that anyone who presumes henceforth to assert defend or hold stubbornly that the rational or intellectual soul is not the form of the human body of itself and essentially, is to be considered a heretic." (This council was an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church.) However, Professor Kemp maintains that Adam and Eve had "biologically human ancestors" (p. 232), who belonged to a "biologically (i.e., genetically) human species" (p. 231), so it seems that he must therefore hold that these pre-Adamite hominids had human bodies; yet he also says that these hominids lacked rational souls - which means that for Kemp, the rational soul is not essentially the form of the human body. Now, Professor Kemp is a loyal and devout Catholic, and I do not wish to question his orthodoxy, but I think he owes his readers a better explanation of how he would reconcile his declared views with the official teaching of the Catholic Church than the brief and rather cryptic remark he makes in a passage near the conclusion of his article. In that passage, Kemp attempts to reconcile his position with the statement of the Council of Vienne by declaring that "Adam's non-intellectual cousins would have had a sensitive soul sufficient to engage in all the acts of image apprehension and manipulation of which other animals are capable, without the power to abstract from those images the concepts that distinguish human from animal cognition" (p. 235). All well and good; but on Kemp's account, Adam's cousins still had human bodies, yet they lacked rational souls – which entails that the rational soul is not essentially the form of the human body.

Professor Kemp might attempt to respond by saying that Adam's immediate ancestors were biologically human, but did not have human bodies – an assertion that I find altogether unintelligible. For although Adam's ancestors lacked the power of reason, which is a spiritual capacity, their bodies still possessed exactly the same set of capacities that our bodies possess, according to Kemp. Hence they must have been human bodies. I've said it before and I'll say it again: if you're a biologically human being, then you're a human being. And if you're a human being, then you must have a human body.

But perhaps what Professor Kemp has in mind can be better illustrated by the following example. Imagine a creature with natural capacities A, B and C, which arise from its form - i.e. that which makes it the kind of thing it is. Now imagine another kind of creature with the same natural capacities, plus another capacity D. Since this creature has a different set of natural capacities, it must be a different type of entity, and must therefore have a different form. Now suppose that A, B and C are the bodily capacities which make a creature biologically human, and D is the capacity to reason, which is a non-bodily capacity. Professor Kemp would argue that "philosophical man" (i.e. man the rational animal) is the second kind of creature, and that the human soul which the Council of Vienne is referring to is simply the form of this kind of creature, and not the first kind (biological man). Problem solved, right?

Well, I don't buy that "solution", for two reasons. For one thing, both of these creatures have exactly the same bodily capacities: A, B and C. Consequently, if the second creature (philosophical man) has a human body, then so does the first creature (biological man). However, if biological man has a human body but lacks a rational soul, then the human soul cannot be the essential form of the human body - which (once again) seems to put Professor Kemp's position at odds with that of the ecumenical Council of Vienne.

For another thing, it is simply absurd to suppose that there can be two different kinds of creatures, possessing exactly the same bodily capacities (A, B and C), but different non-bodily capacities (none at all for biological man, versus capacity D for philosophical man). Once we understand what an Aristotelian soul is, we can immediately see why this idea makes no sense. On Aristotle's account, the soul is not only the formal cause of the body (i.e. that which makes it the kind of body it is), but also its final cause (i.e. that which endows a living thing with a "good of its own", or telos). In other words, the powers of the soul are precisely those powers which it should fittingly have, given the kind of body it has. Consequently, if two creatures have the same kind of body, then they must have the same kind of soul.

Now, the really odd thing about human beings is that they are animals with two non-bodily capacities (the capacity to reason coupled with the concomitant capacity to make free choices), in addition to their bodily capacities. How, the reader may be wondering, can there be a kind of animal which, by its very nature as an organism, should possess non-bodily capacities, in addition to its bodily capacities? The answer, as I'll argue below, is that if the body's physical powers alone are insufficient to make an organism suitable for its biological role or niche, then it must rely on additional, non-bodily powers in order to fit into that role. So, what's the role of a human being? Following Aristotle, Aquinas would say: we are not solitary beings; thus the human telos is essentially social. At the very least, it involves being a committed member of a monogamous nuclear family, as well as an active member of a local political community - be it a tribe or a nation-state. Both the domestic and political roles of a human being require the use of reason - in particular, an ability to engage in long-range planning, as well as an ability to put oneself in another person's shoes (or else we could not follow the Golden Rule). Both of these abilities are rational abilities. As primates, human primates are social animals, who are physically well-adapted to fulfilling their domestic and political roles; however their bodily capacities alone are insufficient to allow them to fulfill these roles. Professor Kemp and I would both agree that having a big brain doesn't automatically give you empathy or the ability for long-range planning. Thus the human primate is an organism that naturally requires the use of incorporeal reason, in order to be the kind of thing it is.

Incidentally, I'd like to note in passing that back in July 2000, Professor Kemp delivered a lecture entitled, The Theory of Evolution as part of a series of three talks given at the Thomistic Summer School in Birstonas, Lithuania, in which he put forward essentially the same hypothesis that he recently published in his 2011 paper, Science, Theology and Monogenesis, but without the awkward terminology that distinguishes between three different types of man (biological, philosophical and theological). In his earlier talk, given in 2000, Kemp simply says that the population of 5,000 hominids consisted of "beings which look rather like human beings, but lack an intellect". If he had simply said that in his recent paper, without inventing a spurious distinction between "biological man" and "philosophical man", he might have saved himself a lot of bother.

Nevertheless, readers may still be wondering whether Professor Kemp had a valid point in his recent paper. After all, if (as Aquinas maintains) each human person's soul is created by a special act of God, then it would seem to follow that if an individual could be generated with a body like ours, but without a rational soul being infused by God, then it would have a human body without a rational soul. In Professor Kemp's terminology, it would be "biologically human" without being "philosophically human" (i.e. rational); and it would certainly not be "theologically human" (i.e. able to be on friendly terms with God).

My reply to this objection is that the antecedent is impossible: no individual could ever be generated with a human body, but without a human soul. "Why not?" you may ask. The answer is that a human body is the kind of body that requires a rational soul in order to properly flourish; human beings, as a race, require the use of reason for their very survival, and without the ability to reason, the human race would not be viable and would swiftly perish. (I'll explain why in more detail in my next post. All I'll say for now is that given the kind of bodies that human beings possess, an extraordinary level of co-operation would have had to develop between members of each human community, in order that they could satisfy their energy requirements and feed themselves adequately. This level of co-operation would have required the ability to reason.) As a devout Catholic, Professor Kemp would surely hold, as I do, that God intended the process - whether it was natural or supernatural is irrelevant here - by which the human body originally came into existence. Since human beings, as a biological life-form, require the use of reason for their very survival (as I shall attempt to show in my next post), then God could never intend that human beings, as a life-form, should come into existence without also intending that they should have a soul which is suited to their biological nature: namely, a rational soul, which (unlike the soul of a non-rational animal) requires a special act of creation by God. Since this generic intention on God's part would apply to the entire human species, it must apply to each of its members. Consequently, it is impossible that God could allow a human creature to come into existence without endowing it with a rational soul - for if He did, He would be contradicting His own will for the human species as a whole.

A fifth reason for rejecting Professor Kemp's three-way fragmentation of the concept of humanity is that it is morally hazardous in its implications. For it seems to imply that we can never know for sure whether any human being who has never exercised, or who can no longer exercise, his/her reason is actually a person with a rational soul or merely a sub-rational, biologically human animal. I have recently argued, in my online essay, Embryo and Einstein: Why They're Equal, that the human rights of the embryo are grounded in its biological humanity, which is why an effective pro-life case can be effectively made even when arguing with atheistic materialists, so long as they are prepared to grant at the outset that rational human adults have a natural right to life. Given that admission on their part, it can be demonstrated that embryos also have a right to life. (If you're a materialist, then of course, you'll hold that our capacity to reason is ultimately grounded in the developmental program in our genome, which is present from the moment of conception; and if you reject materialism, then you'll still hold that it is grounded in human nature, which is also present from the very beginning.) Sadly, many pro-choice proponents have, in recent years, attempted to argue that the human capacity to reason is imparted to the developing fetus from its external environment – a position I have refuted in my online essay. These pro-choice advocates acknowledge that the embryo/fetus is biologically human, while denying that it possesses a rational nature – hence, they say, it is not a person. As I see it, the danger of Professor Kemp's fragmentation of the concept of humanity is that it is vulnerable to being misused by pro-choice proponents to further their cause.

Kemp, who is ardently pro-life, would doubtless respond by saying that if the embryo/fetus lacked a rational nature, then it would have to undergo a change of nature at some subsequent stage of its development, when God gave it a rational soul - a philosophically unparsimonious hypothesis - and that it makes more sense to say that it possesses a rational nature from the moment of conception. Indeed, Kemp does explicitly state, in a footnote on page 233 of his article, that God's giving an existing individual a rational soul "would make it a different kind of being and a fortiori a different individual." However, a pro-choice advocate could reply that when a human person acquires his/her capacity to reason, it is merely superimposed on its existing biological humanity, without changing the fetus' underlying biological nature. On this proposal, when a new human person emerges at some time subsequent to conception, it still remains the same individual animal as it was before becoming a person. I am sure that Professor Kemp would strongly object to this response, but it is difficult to see how he could rule it out, given the real (and not merely logical) distinction he has drawn between our biological humanity and our rationality.

The only way to decisively refute the pro-choice line of argument described above is to show that our rationality and our animality both spring from a common source: our human nature. As Aquinas would say, to be a human animal is to be an animal which is by nature rational. (This was a point which Aquinas never lost sight of: for even though he was misled by the faulty biology of Aristotle into believing that the fetus did not become an animal until several weeks after conception, he nevertheless insisted that the fetus acquired rationality at the same time as it became an animal. Thus for Aquinas, our rationality is part and parcel of our animality.) But Professor Kemp cannot argue in this manner, because he believes that being biologically human does not entail having the capacity to reason. On his view, rationality is something which can be tacked onto an existing biologically human animal. Thus Kemp's proposed distinction between three concepts of humanity (biological, philosophical and theological) severely hampers the pro-life case – needlessly, I might add, since the very unity of human nature attests to the fact that our rationality and our animality both spring from a common source. It is one and the same "I" who reasons, chooses, senses, desires and obtains nourishment.

In this post, I have been chiefly concerned to argue that the concept of humanity is one which we rend asunder at our philosophical peril. Human beings are rational animals, and our rationality is precisely what characterizes us as animals, for our whole way of life, as a species, requires us to be able to engage in reasoning, as I shall argue in my next post.

When did human rationality first appear? Is our ability to reason a single, universal capacity that appeared all at once, or a cluster of capacities which appeared gradually over the course of human evolution? Who were the first human beings, and what can science tell us about them? Was there a single original pair, or did the human stock never fall below 5,000 individuals, as many biologists claim? These are the questions that I'll be addressing in my second post on Professor Kemp's recent article, Science, Theology and Monogenesis (American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, 2011, Vol. 85, No. 2, pp. 217-236). In my previous post, I focused on the philosophical flaws arising from Kemp's attempt to distinguish three different concepts of humanity: biological (belonging to the human species, genetically speaking: i.e. being a member of a population which inter-breeds with people), philosophical (having a natural ability to reason, by virtue of possessing a spiritual soul) and theological (having the opportunity to be in a state of eternal friendship with God). In this post, however, I'll be assessing Kemp's article strictly on its scientific merits.

Let me say at the outset that as someone who has had an interest in prehistoric man since childhood, I was quite impressed with the breadth of Professor Kemp's reading and the fairness of his reporting of scientific findings. Kemp has made a commendable attempt to do justice to his subject matter, and his argument therefore warrants serious scientific evaluation.

Professor Kemp's article, although well-researched, suffers from three scientific flaws. The first is a mild bias towards methodological naturalism. Underlying Kemp's paper is an implicit assumption that even if (as he believes) evolution is guided by God, evolution must always be an entirely natural process, requiring no extraordinarily unlikely occurrences that would need to be "specially arranged" by an Intelligent Being - whether by directly manipulating certain individuals' genes, or by pre-arranging that certain mutations should occur through some kind of "front-loading" process (e.g. at the Big Bang, or at the dawn of life). Unfortunately, Kemp’s methodological naturalism leads him to overlook scientific evidence suggesting that intelligent engineering of the human genome did indeed occur in our evolutionary past. In particular, there is strong prima facie evidence of intelligent engineering of the genes that regulate the development of the human brain over the past few million years. It is a pity that Kemp does not consider this possibility. The irony here is that Kemp himself believes that God infused a spiritual soul into two hominids at the dawn of human history, and that He has been infusing souls into the bodies of all their descendants ever since. That makes him what philosopher Daniel Dennett would call a "mind creationist". In the view of today's Gnu atheists, this position is simply "a form of Intelligent Design", as evolutionary biologist Professor Jerry Coyne pithily put it in a recent post entitled, Simon Conway Morris becomes a creationist (14 February 2009). If Professor Kemp already holds to a position that orthodox evolutionists dismiss as "creationism" and/or "Intelligent Design", then surely the old adage, "One might as well be hung for a sheep as for a lamb", applies here. What does Kemp have to lose by investigating the possibility that the evolution of the human brain was engineered by God, and that the critical mutations which gave our hominid ancestors human brains and bodies were intelligently planned?.

My second scientific criticism of Kemp's article is that his definition of a biological species is a little muddled. The definition of a species is an important matter, for it has bearing on the question of whether Adam and Eve's descendants would have been able to inter-breed with other hominids. I shall argue below, on the basis of paleontological evidence, that the first hominids that could be called rational - and hence human - probably possessed various genetic and physical attributes that would have inhibited their mating with other hominids, and that if they did, these features could fairly be described as barriers to reproduction. I shall contend that the combined effect of these barriers would have meant that if there were only two rational individuals (Adam and Eve) at the beginning of human history, there would have been little likelihood of them or their descendants successfully inter-breeding with other hominids. Thus even if Adam and Eve were not already a biologically distinct species from their sub-rational hominid contemporaries, the barriers to reproduction separating them from other hominids would have led to their descendants becoming a distinct biological species within a relatively small number of generations, simply as a result of reproductive isolation.

The third and most important flaw in Kemp's paper is that he overlooks a number of scientific facts, which suggest that for the first human beings, the ability to reason would have been absolutely critical for their survival. Without this incorporeal capacity, the first human beings would have ceased to be biologically viable and would have swiftly died out as a race. My argument is based on the empirical fact that having a human body comes at a very high evolutionary price, and that additionally, many features of the human body are biologically disadvantageous as such: for example, the large human brain, which consumes an inordinate amount of oxygen; the human pelvis, which is not always wide enough for a baby's head to pass through; naked skin, which offers inadequate protection against the cold; small canines, which are of no use in fighting; and feet which are adapted for bipedalism rather than gripping, making it impossible for human infants to cling to their mothers' bodies with their feet, as chimpanzee infants do. Indeed, I shall argue that so great are the biological drawbacks associated with having a human body that only the possession of reason could adequately compensate for these drawbacks.

Next, I shall examine three objections that might be raised to the thesis I am proposing here - first, the various biologically disadvantageous traits distinguishing human beings did not appear simultaneously, but gradually, over millions of years, giving our hominid ancestors plenty of opportunities to adjust their lifestyles in order to cope with these deleterious traits; second, that these disadvantageous traits may have been offset by biological benefits; and finally, that even if a cognitive benefit were needed to compensate for the appearance of these biologically disadvantageous traits, it need not have involved a qualitative change in our ancestors' mental capacities, but merely a quantitative one - and hence, there would have been no overnight leap in our ancestors' cognitive abilities, as believers in an immaterial soul would maintain.

I shall respond to these objections by providing evidence that around 2,000,000 years ago, human evolution reached a critical threshold in terms of our ancestors' food and energy requirements. This is the time when Homo erectus emerged. (Note: In this post, I will be using the term Homo erectus fairly broadly, to include the earlier specimens of Homo ergaster from Africa, as well as the Homo georgicus fossil remains from Dmanisi, Georgia.) Following the work of authors such as Mathias Osvath and Peter Gardenfors (see their 2005 paper, Oldowan culture and the evolution of anticipatory cognition) and also Kit Opie and Camilla Power (vide their 2008 article, Grandmothering and Female Coalitions: A Basis for Matrilineal Priority?), I argue the food and energy requirements of Homo erectus could only have been satisfied if adult males and females had the capacity to make long-term family commitments held together by strong bonds, which pre-supposes an ability to plan for the long-term future. In other words, Homo erectus must have been rational – or else he would have starved to death as a species. The foregoing considerations would apply even more strongly to Heidelberg man (Homo heidelbergensis), who lived from 700,000 to 300,000 years ago, and who was built like Homo ergaster (African Homo erectus), but who was somewhat taller (1.8 meters), with an average brain size of 1225 cubic centimeters, placing him well within the modern human range. In the interests of journalistic accuracy, I would like to point out that none of the authors whom I will be citing believe that human rationality appeared overnight, as Professor Kemp and I both do; indeed, Osvath and Gardenfors, who endorse a materialistic account of human cognition, envisage that our ability to plan for the future developed gradually during the Oldowan period, over a period of about one million years, when early Homo made tools, before making itself unambiguously manifest in Homo ergaster/erectus. However, the key point that I wish to make in quoting these authors is that at some stage in human history, a critical threshold was crossed in terms of our ancestors' food and energy requirements, which made the possession of human rationality a practical necessity.

To buttress my case, I shall also argue that the Acheulean toolswhich were often used by Homo erectus, starting from at least 1.8 million years ago, display very strong indications that their makers were capable of taking a carefully controlled sequence of steps in order to achieve a long-range goal (e.g. A->B->C->D), which means that they were rational individuals. For instance, it takes about 45 minutes of sustained, focused activity to make an Acheulean hand axe. Only a creature that was capable of performing various steps in a specified order in order to realize a long-term goal would have been capable of such a task. (I would like to note in passing that Professor Kemp is also impressed by the tools made by Homo erectus, and I am happy to see that he apparently shares my view of Homo erectus's tool-making capacities, judging from his remarks on page 234 of hisarticle.) Finally, the later Acheulean tools made by Heidelberg man 500,000 years ago were even more elegantly fashioned, leaving absolutely no doubt as to the intelligence of their designers. Thus we can be reasonably confident that rational human beings existed nearly two million years ago, and absolutely certain that they existed half a million years ago.

I shall also discuss other activities engaged in by Homo ergaster/erectus which give us good reason to believe that this species was rational: first, the controlled use of fire for cooking meat (dating back to at least 1,900,000 years ago); second, the ability to catch fish (at least 750,000 years ago); third, the ability to make either boats or rafts for sea voyages (at least 850,000 years ago); fourth, the creation of tools that were evidently designed to be objects of beauty (at least 750,000 years ago); and fifth, the care that was given to sick individuals over a prolonged period of time, demonstrating the existence of human compassion (1,800,000 years ago). Taken together, these practices very strongly suggest that Homo ergaster/erectus was a rational creature, and therefore a human being.

Next, I shall critique scientific evidence which has recently been put forward, suggesting that human rationality is not a single capacity, but a cluster of related capacities which appeared at different times in human history, and that our ancestors did not become mentally human overnight. In a ground-breaking article entitled, Paleolithic public goods games: why human culture and cooperation did not evolve in one step (Biology and Philosophy, 2010, 25:53–73, DOI 10.1007/s10539-009-9177-7), Dr. Benoit Dubreuil has argued that while hominins from the early Pleistocene period (about 2,500,000 to 800,000 years ago), such as Homo erectus, possessed the capacity to form mental representations of complex social norms, emotions and goals, and were also capable of collaborating for the realization of future goals, it is only with the appearance of Homo heidelbergensis, about 700,000 years ago, that we see the true emergence of the characteristically human abilities of sticking to abstract goals, in the face of conflicting motivations - i.e. exercising self-control and foregoing short-term individual gain for the sake of a larger long-term reward which benefits the group as a whole. Dubreuil argues that this ability would have been essential in order for individuals to adhere to the very demanding co-operative requirements involved in big-game hunting and life-long monogamy. Finally, Dubreuil contends that at an even later phase, somewhere between 300,000 and 100,000 years ago (i.e. approximately the time when modern Homo sapiens emerged), human beings developed new cognitive abilities – namely, a capacity for symbolism, art, and a properly cumulative culture, which was able to build on previous innovations. Dr. Dubreuil believes that Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis lacked these distinctively human abilities. Thus Dubreuil would argue that the possession of distinctively human cognitive capacities is not an all-or-nothing affair, but one admitting of several degrees; hence our ancestors could not have become rational overnight. However, Professor Kemp and I would both maintain that our hominid ancestors did become rational literally overnight, when the first human soul was infused into a human body.

Contra Dubreuil, I shall first argue that any convincing attempt to isolate the various capacities that we commonly classify together as "rational" requires a clearly defined procedure for grading these capacities into different levels of rationality, as well as a detailed cognitive model of the human mind, which predicts exactly which of the various cognitive capacities we associate with human beings should be capable of existing independently of the other capacities, which capacities should always be associated together, and finally what order these capacities should appear in, during our evolutionary history. (For example, could there have once been a hominid who was naturally capable of creating art, but inherently incapable of religious beliefs, or of making scientific observations?) Neither the required procedure nor the detailed cognitive model has yet been developed, so I remain skeptical of Dr. Dubreuil’s attempt to fragment the human capacity to reason. (To be sure, Dubreuil proposes a plausible neurological model, based on a posteriori reasoning coupled with some good scientific guesswork; but what I am looking for is a model of the mind as such, rather than the brain. I want to know why we would expect the emergence of cognitive capacity X to precede that of capacity Y in human history.)

Second, I shall contend that there is in fact considerable evidence suggesting that large-scale, long-term co-operation, which Dr. Dubreuil claims first appeared with Homo heidelbergensis, was already present in Homo erectus, and that the ability to create symbolic art, which he regards as unique to modern Homo sapiens, was already present in Homo heidelbergensis.

Third, I shall suggest that if Homo erectus and/or Homo heidelbergensis were deficient in any mental ability, it was not the ability to reason or to understand the intentions of other minds, but more likely, a much lower-grade ability: the ability to ascribe a symbolic significance to objects. Perhaps Homo erectus was unable to think thoughts like: "This object symbolizes individual A, while that object represents individual B." This limitation would have meant that Homo erectus was unable to create symbolic art; nevertheless, he would still have been able to create objects of beauty (such as elegantly crafted Acheulean tools).

Finally, I shall propose a definition of human reason which provides grounds for thinking that it is indeed an all-or-nothing ability: we ascribe reason to someone who is capable of adhering to sequentially ordered rules for the sake of achieving a distant goal, which he/she is able to share with other people. I shall argue that anyone who is capable of doing this must also be capable by nature of engaging in practices such as science, art and religion.

As a Catholic philosopher, Professor Kemp, like myself, is committed to the belief that the human ability to reason appeared at a definite point in human history, and that it is an all-or-nothing affair. Scientific proof to the contrary would, as I shall argue, be absolutely fatal for both Judaism and Christianity: a spiritual soul (which is required for reasoning) is something that you either have or you don't, and it does not come in "grades" - which is why all human beings are equal. In my opinion, the attempted fragmentation of the human capacity to reason by prominent cognitive scientists and anthropologists presents a far greater threat to the Abrahamic faiths than the difficulty of reconciling human genetic diversity with the Biblical account of Adam and Eve. I might add that if Professor Kemp is willing to maintain (as I do) that the human ability to reason appeared overnight, in the face of archaeological and neurological evidence suggesting the contrary, then he has no good reason to jettison the traditional Judeo-Christian belief that all human beings are descended from one and only one couple, simply because the genetic evidence strongly suggests otherwise. If Professor Kemp wants to take his epistemic lead from science and modify his understanding of Christian doctrines in the light of modern discoveries, he should be consistent about it.

Next, I will argue that among the biological features that distinguished Homo erectus - the first hominid for whom the ability for abstract reasoning became vital to its survival – from other hominids, were changes which dramatically affected its genetic make-up and its appearance. I discuss three changes in particular, which may have coincided with the emergence of Homo erectus, 2,000,000 years ago: first, a change from 48 chromosomes per body cell to 46, which occurred somewhere between 740,000 and 3,000,000 years ago and may well have coincided with the appearance of Homo erectus 2,000,000 years ago; second, a massive increase in the number of sweat glands (enabling our ancestors to run long distances in pursuit of prey, without getting over-heated), which probably occurred at the time when our ancestors acquired smooth, hairless skin; and third, a total loss of body hair (which would have also helped our ancestors to radiate excess body heat), a process which was fully completed by 1,200,000 years ago at the latest. I argue that the sudden change in chromosome number would have hindered (but not totally prevented) inter-breeding between humans with 46 chromosomes and other hominids, who had 48. I then speculate that if the other changes (a profusion of sweat glands and a loss of body hair) occurred at the same time, they may well have rendered Homo erectus individuals sexually unattractive to other non-rational hominids, creating a pre-copulatory barrier to reproduction. (For instance, a hairy australopithecine female, with relatively few sweat glands, would probably have been strongly repelled by a hairless and very sweaty Homo erectus male, and vice versa.) The combined result of these genetic and physical changes is that rational and non-rational hominids would have been strongly disinclined to inter-breed from the very beginning. Thus I tentatively suggest that an evolutionary bottleneck occurred around 2,000,000 years ago - a date which was originally proposed by paleoanthropologist John Hawks et al. in 2000 (see "Population Bottlenecks and Pleistocene Human Evolution," Molecular Biology and Evolution 17 (2000): 2–22). However, unlike Hawks, who is an orthodox evolutionist, I hold that this bottleneck consisted of just two individuals: Adam and Eve.

The notion that the human race is descended from a single original couple is now widely discredited, following studies conducted by Professor Francisco J. Ayala ("The Myth of Eve: Molecular Biology and Human Origins," Science 270 (1995): 1930–6; and, with A. A. Escalante, "The Evolution of Human Populations: A Molecular Perspective," Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 5 (1996): 188–201), which supposedly demonstrate that humans could never have descended from a stock of just two individuals. According to his research, at no stage in our hominid past did the population ever fall below 15,000 individuals. Professor Kemp is evidently impressed by Ayala’s work, for he devotes considerable space in his article to explaining the scientific reasoning underpinning Ayala's studies. Professor Ayala bases his conclusion on his studies of variation in a particular gene in the human population: the DBR1 gene, which is one of many genes that make up the human leukocyte antigen complex. However, I shall argue below that this particular gene is under very strong selection for increasing diversity, making it a poor choice for making estimates about genetic events in our distant past.

Professor Kemp also points out in his essay that other studies have backed Ayala's conclusions. These studies are handily summarized in an article written for the Biologos Foundation, entitled, Genesis and the Genome: Genomic Evidence for Human-Ape Common Ancestry and Ancestral Hominid Population Sizes, by Dr. Dennis Venema, a biochemist who is also an evangelical Christian. In his article, Venema attaches great significance to the fact that gene trees in human beings don't always match species trees: the chimpanzee is our nearest relative, but a few of our genes are more like those of gorillas than those of chimps. Venema explains this fact by positing that the ancestral population from which humans and chimpanzees sprang was large enough, and genetically diverse enough, to transmit a few gorilla-like genes to us without passing them on to chimpanzees. Chimpanzees and humans are both descended from this large, diverse ancestral population, whose effective size is now estimated at 8,000 to 10,000 individuals. What Venema is doing here is arguing from naturalistic assumptions: he is assuming that some random event is responsible for the fact that some of our genes are more gorilla-like than chimp-like, and his effective population size estimates also assume that gene flows are random, rather than intelligently guided. An Intelligent Design proponent would ask why some of our genes are more gorilla-like than chimp-like, and consider the possibility that humans were deliberately designed that way - a fact which is perfectly compatible with common descent. In short: you can only rule out monogenism if you have already adopted methodological naturalism. Intelligent Design proponents reject this methodology, as it attempts to put science in a box: super-human intelligent causal agents are excluded on an a priori basis from the domain of legitimate scientific explanations.

The foregoing genetic arguments do establish, however, that a human genetic bottleneck of two individuals could never have arisen as a result of unguided natural processes. Additional reasons for positing intelligently guided genetic engineering in our evolutionary past include the large number of genetic changes that would have been required to produce a brain that was compatible with a rational soul, and at the same time inhibit inter-breeding between rational humans and non-rational human-like hominids at the dawn of human history - assuming that our Creator meant to actively discourage humans from inter-breeding with other creatures Personally, I am agnostic as to whether this genetic engineering was achieved by some sort of "front-loading" at the dawn of life (thus avoiding the need for subsequent Divine "intervention") or whether our Creator directly manipulated the hominid genome two million years ago, although I incline toward the latter hypothesis.

Some religious believers find the notion of Divine genetic engineering deeply distasteful. For my part, I believe that we should keep an open mind. We might find such a notion messy and inelegant, but God is not bound by our personal "aesthetic" preferences, which are often merely disguised theological biases - and in any case, that may have been the least inelegant way for Him to accomplish His objectives for the human race.

Lastly, supposing that some kind of Divine genetic engineering did take place at the dawn of humanity, I shall attempt to describe what kinds of processes might have been involved. Here, I would like to acknowledge my debt to Gnu atheist Professor Jerry Coyne, who recently put up a mocking post (11 June 2011) describing exactly what kind of miracle would have been required in order for monogenism to be true. Unlike Coyne, I see no reason to doubt that such a miracle occurred, and I would like to add that I find it ironic that the atheists who balk at this miracle seem to have no trouble believing that the most complex machine in the universe emerged by an unguided process. Now that's a miracle, if ever I heard of one.

1. Why is Professor Kemp willing to adopt methodological naturalism when discussing our biological origins, when modern science is completely unable to explain the evolution of the human brain?

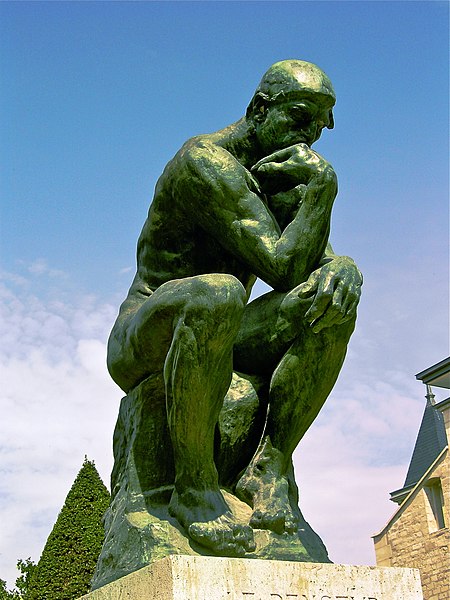

Diagram showing the lobes of the human cerebral cortex and the cerebellum (blue). The brain is seen from the right side, the front of the brain (above the eyes) is to the right. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

On pages 230-231 of his article, Professor Kemp evaluates a proposal put forward in 1964 by Andrew Alexander C.J., ("Human Origins and Genetics," Clergy Review 49 (1964): 344–53), in which he suggested that "while it is true that all men are descended from Adam, the race nevertheless had a broad origin." Like Kemp, Alexander envisaged inter-breeding between the first humans and their hominid contemporaries; unlike Kemp, Alexander believed that a final mutation was required to make Adam and Eve biologically human, before God could infuse them with a soul. Kemp rejects this hypothesis as scientifically unlikely:

In Alexander's account, the material condition of this ensoulment was the appearance of a suitable body (rendering the account compatible with the demands of hylomorphic philosophy), which he interprets genetically as the result of a final crucial mutation. This mutation, he suggested, crossed a philosophically or theologically critical threshold, but did not establish biological barriers to reproduction…I think that Alexander's distinction between the biological species (the population of beings capable of interbreeding) and the philosophical and theological species "human being" is the key to the solution of this problem, but that his emphasis on genetics (a crucial mutation) may be misplaced. It creates for him the necessity to posit a not impossible but extremely unlikely co-occurrence of exactly two instances of the same mutation (one in a man and one in a woman) at roughly the same time. (Emphasis mine – VJT.)

Professor Kemp's argumentation in this passage reveals a bias towards methodological naturalism, when attempting to account for our biological origins as human beings. Like Kemp, I accept the fact that human beings and chimpanzees share a common ancestry – for I can think of no other satisfactory explanation for the pervasive similarities humans and chimps share at the genetic level, notwithstanding the pronounced differences that also exist. Unlike Professor Kemp, however, I see no reason to infer, from the mere fact of our common ancestry with the chimpanzee, that secondary causes, conserved by God and operating in their usual manner, should be sufficient to account for the origin of the human body. Maybe they are, and maybe they aren't.

Looking at the human body, I can see plenty of reasons for doubting a purely naturalistic account of our biological origins. Consider, if you will, the origin of the human brain – easily the most complex structure known to exist in the entire universe. No machine that human beings have built comes close to matching it in processing power. And now compare the brain of a chimp, a gorilla or an orang-utan with a human brain, and ponder the profound differences between the human brain and those of the great apes. How did we get to be the way we are? And why can our brains do so much more than those of the great apes?

Unfortunately, many contemporary scientists have a tendency to glide over the evolutionary difficulties of generating a human brain from the chimp-sized brain which the common ancestor of humans and chimps must have possessed. Popular scientific explanations for the evolution of the human brain include: incremental growth at a steady pace over the last few million years; neoteny, which kept our brains growing longer during infancy and thereby made them much bigger when mature; an enlargement of Broca's area, which is related to language production; and a couple of mutations in our FOXP2 genes, giving us the ability to make grammatical sentences. Here is a fairly typical example of a "Just so" story about how the human brain evolved, taken from a recent post by Professor Jerry Coyne, entitled, Is the human mind like a skunk butt? (30 May 2011):

So long as advantageous mutations occur, regardless of their rarity, natural selection can build a complex brain without "catastrophe." And it had about five million years to turn a chimp-sized brain into ours. Just looking at volume, and assuming an ancestral brain of 500 cc, a modern brain of 1200 cc, and a generation time of 20 years, that's a change in brain volume of 0.0028 cc/generation, or an average increase of 0.00056% per generation. Where's the evidence that this change - at least in volume - was too fast to be caused by selection? We know that current observations of selection, such as that seen in beak size in Darwin's finches, can be much stronger than this without catastrophic effects! The finches, after all, are still here, and behaving like finches.

This is an illegitimate extrapolation: the chasm between the chimp-sized brain of Australopithecus and the modern human brain was not traversed by growing in cubic centimeters, but by growing neurons - and about 250,000 extra neurons must have been added per generation, if evolution proceeded at a uniform rate. Alternatively, we might suppose that every so often, neurons were added to the evolving human brain, in one fell swoop - say, a sudden burst of 2.5 billion neurons, every 100,000 years. Both scenarios have their problems, as Marshall Brain points out in an unusually candid article entitled, How Evolution Works: How Can Evolution Be So Quick? on How Stuff Works:

We see no evidence that evolution is randomly adding 250,000 neurons to each child born today, so that explanation is hard to swallow. The thought of adding a large package of something like 2.5 billion neurons in one step is difficult to imagine, because there is no way to explain how the neurons would wire themselves in. What sort of point mutation would occur in a DNA molecule that would suddenly create billions of new neurons and wire them correctly? The current theory of evolution does not predict how this could happen.

This isn't an argument from ignorance that I'm putting forward here. If I see a device that's better built than anything that our best scientists could have come up with, then it's entirely reasonable for me to infer that some super-intelligent agent designed it – especially if I am unable to come up with a not-too-improbable pathway whereby the device might have assembled itself without intelligent guidance. The human brain is such a device. Nothing we've built comes close to matching its awesome power – and everything we learn about it increases, rather than diminishes, our awe.

See also Why the human brain is not an enlarged chimpanzee brain:

Comparative neuro-anatomical studies (e.g., Barton et al., 1995) show that primate brains not only differ in size, but also in internal organization and structure. Interestingly, this organization reflects a species’ ecology and social structure, rather than its cladistic relatedness. For example, woolly monkeys (Lagothrix poepigii), a species of New World monkeys, have an energy-rich diet consisting mainly of fruits and insects. As a result, the internal organization of their brains looks vey similar to that of chimpanzees and differs considerably from that of other closer related New World monkeys (De Winter and Oxnard, 2001). Rilling and Insel (1999) compared the brains of 44 primate species using magnetic resonance imaging. Their research indicates that the human brain is not simply an enlarged ape brain: some areas have grown allometrically in humans, such as the prefrontal and temporal cortices, which are involved in language and theory of mind, whereas others, such as the cerebellum, which deals with locomotion, are reduced when compared to orang-utans and gibbons. Interestingly, the corpus callosum, which connects areas of similar function between the hemispheres, is reduced in humans compared to other apes. This reduced connectivity allows for greater autonomy and divergent evolution of different brain regions which may have enabled left-lateralization of language and cognitive functions (Hopkins and Rilling, 2000).As a matter of empirical fact, then, the human brain does not appear to be an enlarged chimpanzee brain. (p. 170) (Emphasis mine – VJT.)

The authors go on to argue that "both ecology and social structure are important factors in cognitive evolution" - a fact which I do not doubt for a moment. However, the question at stake is whether they are sufficient to account for the cognitive specializations of the human brain, and this I am strongly inclined to doubt. The very evidence which Hogh-Olesen et al. provide for their claim undermines it: for instance, when discussing the unique ecological niche occupied by human beings in distinction to the other apes, they write that "humans prefer food that is harder to obtain - through hunting and extraction - but that is high in energy and nutritive value", and that "Humans are unique among primates in their obligatory reliance on tools to extract food" (p. 172). But this begs the question: how did the ancestors of humans acquire the mental wherewithal to make these tools? Darwinian evolution is a process that lacks foresight. The idea of a hominid's brain evolving in a certain direction in order that its descendant might become smart enough to make tools that would allow it to extract certain foods isn't Darwinian evolution. It's Intelligent Design.

So when I hear theologians telling me that the human race descended from an original couple, and geneticists telling me that such a scenario is at odds with a naturalistic account of human origins, I don't believe we should automatically assume that human evolution has been an unguided naturalistic process. Professor Kemp's acceptance of the geneticists' verdict is therefore a rush to judgment, in my opinion.

2. What is a biological species?

The fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. Image courtesy of Andre Karwath and Wikipedia.

One scientific flaw of Kemp's paper is that his definition of "biologically human" is somewhat inconsistent: on page 230, he declares that "The biological species is the population of interbreeding individuals" (which is reasonably accurate), while on page 231, he defines a "new biological species" as "a new population of organisms incapable of interbreeding with the remainder of the larger population among which they appeared" (italics mine). This definition implicitly assumes that the mere ability of one individual to inter-breed with another makes them both members of the same species, which is not the case. It is quite possible that humans are still able to inter-breed with chimpanzees (see this article), despite having diverged from them six million years ago; yet no-one would say that they were of the same species.

The late Professor Ernst Mayr defined a biological species as follows: "species are groups of interbreeding natural populations that are reproductively isolated from other such groups." For instance, two identical-looking birds – the Western meadowlark and the Eastern meadowlark – are classified as different species, simply because their distinct songs prevent inter-breeding. It is therefore the absence of barriers to reproduction which makes two individuals to be of the same species. Now, Kemp does mention barriers to reproduction on page 231 of his paper, but he goes on to claim that barriers create "a new population of organisms incapable of interbreeding with the remainder of the larger population among which they appeared." This is not quite correct. A reproductive barrier between two species does not have to make their members incapable of interbreeding, or even incapable of producing fertile offspring; all it needs to do is prevent interbreeding in almost all cases. Such prevention need not be infallible: the two fruit-fly species Drosophila pseudoobscura and Drosophila persimilis are capable of inter-breeding, but a variety of mechanisms (different habitats, different mating times and different mating behavior, as well as reduced inter-fertility) work together to severely restrict the genetic interchange between the two species of fly in the wild. Reproductive barriers may be pre-copulatory, tending to discourage mating; or they may be post-copulatory, preventing matings from producing fertile offspring.

Readers may be wondering: what relevance does all this have to the origin of man? The point I wish to make here is that if the first rational human beings (Adam and Eve, in the Genesis account) had possessed any genetic or physical attributes whatsoever that would have effectively prevented their peers from inter-breeding with them, this would have constituted a pre-copulatory reproductive barrier, setting them apart from their peers and making them the first representatives of a population that would (after a few generations) become so reproductively isolated from its parent population that biologists would classify it as a new species. As I shall argue below, there are grounds for believing that such a reproductive barrier may have appeared nearly two million years ago, with the emergence of Homo ergaster.

3. The evolutionary drawbacks of having a human body

Picture of a Homo erectus male. Image courtesy of Steveoc 86 and Wikipedia.

A more significant scientific flaw in Professor Kemp's paper is that he ignores the numerous evolutionary drawbacks associated with having a human body. Since human infants are the only primate infants who are unable to cling to their mothers with their feet, which are adapted for bipedalism, their mothers would have been forced to carry their babies in their arms while they were foraging for food. Another human drawback is our naked skin, which severely limits humans' ability to withstand the cold. In addition, the increasing size of the human body over the course of our evolutionary history would have undoubtedly increased our energy requirements, which meant that humans would have needed more food in order to survive. On top of that, there is the large human brain, which consumes 20% of the body's oxygen and takes a very long time to mature, compared with that of a chimpanzee. Finally, there is the human pelvis, which is only just wide enough to deliver a human child. Professor Kemp's suggestion that our ancestors may have been biologically human long before they became rational beings presupposes that a non-rational being with a brain and body like ours would be viable, in the evolutionary sense. However, the foregoing considerations suggest that a non-rational being built like us may not have been viable, after all.

Given these biological disadvantages associated with the human body and especially with its large brain, there must have been some compensatory benefit associated with having a larger brain; otherwise hominids having big brains would have been eliminated long ago, by natural selection. I shall argue below that this compensatory benefit was the human capacity for anticipatory cognition (the ability to plan ahead for future needs, requiring abstract reason), and that it was vital to their survival as a group. But abstract reasoning requires a spiritual soul. A large human brain might be necessary for such an ability, but it is certainly not sufficient (a point on which Professor Kemp and I are in perfect agreement). Hence, I would maintain, if significantly larger-brained individuals suddenly appeared in a population of hominids, and if the mutation that generated these larger brains was something planned by God, then He must have also intended to give them a rational soul - for if He hadn't, they would surely have died out.

4. Three objections to the argument that the first humans needed the ability to reason in order to survive

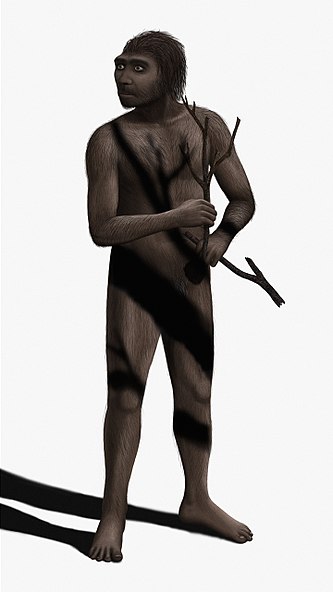

A reconstruction of Homo Habilis, a species that may have preceded Homo erectus. Image courtesy of Lillyundfreya and Wikipedia.

There are three objections that could be made to the line of argument which I am putting forward here: (i) one might hypothesize that the evolutionary drawbacks associated with having a human body did not appear all at once, but gradually, over millions of years, and that humans had time to adapt to these drawbacks; (ii) one might argue that these evolutionary drawbacks were offset by compensatory biological advantages; (iii) one might grant that these drawbacks had to be offset by compensatory cognitive advantages, but argue that these advantages were quantitative rather than qualitative, and that they did not require the possession of abstract reason.

In response to the first objection: it is certainly true that hominids did not become anatomically human all at once. Fully fledged bipedalism (which would have required mothers to carry their infants in their arms) probably appeared around four or five million years ago and was certainly present in Australopithecus afarensis, 3.4 million years ago. Naked skin seems to have emerged much later, with the appearance of Homo ergaster, nearly two million years ago (see here and here), along with sweat glands that made it possible for human beings to run long distances in pursuit of prey without getting overheated. Meanwhile, the human brain, with its high oxygen consumption, has steadily increased in average size over the course of time, from 450 cubic centimeters in Australopithecus africanus (who appeared 3,000,000 years ago) to slightly under 600 cc in early Homo (2,400,000 years ago), to 870 cc in Homo ergaster (who appeared 1,900,000 years ago), to 1250 cc in Homo heidelbergensis (who appeared about 600,000 years ago) and 1360 cc in modern Homo sapiens (who appeared nearly 200,000 years ago). Finally, the large size of a newborn baby's brain would not have rendered childbirth hazardous until the time of Homo heidelbergensis, who emerged about 600,000 years ago. Homo erectus apparently did not have to contend with this problem. (See this press release: "The First Female Homo erectus Pelvis, from Gona, Afar, Ethiopia" , later published in the journal Science, 14 November, 2008.)

My reply to this objection would be that the mere fact that these evolutionary changes appeared at different times in human history does not tell us whether they were viable, from an evolutionary perspective. Was there a critical physical change, a "straw that broke the camel's back", which would have disadvantaged the hominid possessing it to such a degree as to necessitate the emergence of reason? I shall argue below that there was such a change, and that it was associated with the food and energy requirements of infants.

The second objection, like the first, is valid up to a point. The physical changes that occurred in the ancestors of human beings conferred advantages as well as disadvantages. For instance, bipedalism would have made it possible for hominids to travel long distances to get obtain food. It would have also freed hominids' hands for tool use and carrying, in addition to reducing the amount of skin exposed to the tropical sun. Naked skin would have helped prevent the build-up of excess body heat, as well as ridding man's ancestors of a very annoying problem in one fell swoop: fleas. However, the human brain is a very expensive organ to maintain, as it requires a large amount of food. From a strictly biological standpoint, a larger brain would have been a major liability, not an advantage. Similarly, a mother with larger-bodied infants is also biologically disadvantaged, as she has to find more food in order to adequately nourish them.

As regards the third objection: it is certainly true that a large brain confers quantitative cognitive advantages, and a materialist might be tempted to argue that an accumulation of quantitative changes, over millions of years, can explain the differences between human beings and other animals. But the materialist would be mistaken. There are objective, qualitative differences between human beings and other animals, which are scientifically observable. One of these distinguishing features is anticipatory cognition - capacity to form mental representations of the distant future, and plan for future needs. I shall argue below that if we adopt a "tighter" and more rigorous definition of anticipatory cognition than the one which is commonly found in the scientific literature, it does indeed qualify as a capacity which is unique to human beings. I shall also explain why this capacity would have been vital to the survival of Homo erectus.

5. Why growing energy requirements necessitated long-term bonding in our ancestors, which points to the emergence of reason

A scientific reconstruction of Homo erectus, arguably the first rational human being. Image courtesy of Lillyundfreya and Wikipedia.

In this section, I will attempt to show that around 2,000,000 years ago, when Homo erectus emerged, human evolution reached a critical threshold in terms of our ancestors' food and energy requirements, and that their mothers would no longer have been able to forage for their infants on their own. They would have needed assistance from the infants' grandmothers, as well as the infants' fathers. This need would have radically transformed the nature of society for our hominid ancestors. Mothers changed from being self-sufficient foragers to members of a family unit held together by long-term bonds. In other words, the food and energy requirements of Homo erectus infants could only have been satisfied if adult males and females had the capacity to make long-term family commitments held together by strong bonds, which pre-supposes an ability to plan for the long-term future. This means that Homo erectus must have been rational - or else he would have starved to death as a species. The emergence of Homo erectus thus constitutes a biological threshold, at which the possession of human rationality became a practical necessity for survival.

In their paper, Grandmothering and Female Coalitions: A Basis for Matrilineal Priority? (in Allen, N. J., Callan, H., Dunbar, R. and James, W. (eds), Early Human Kinship: From Sex to Social Reproduction, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford, UK, 2009), Kit Opie and Camilla Power identify four distinct stages in hominid evolution. In the first stage, energy requirements were relatively low, and mothers were self-sufficient foragers:

"Among early hominins prior to 2 Ma [million years ago - VJT] who retained significant climbing abilities, brains and bodies were relatively small, with high size dimorphism between sexes." (2009, p. 181)

In the second phase, as babies' brains grew bigger and required more energy, mothers required the assistance of grandmothers, in caring for their infants. Here we see the beginnings of sustained female co-operation, between two generations. However, they would have still been able to care for their babies without paternal assistance:

"From about 2.5 Ma, these species began to encephalize while bodies remained quite small and apparently still highly dimorphic (McHenry, 1996). This suggests increasing costs for females, indicating more pressure for female-female co-operation, while males still had high body-size costs and were less likely to be co-operative." (2009, p. 181)

In the third phase, with the emergence of Homo erectus, adults (especially females) had considerably larger bodies, with much higher energy requirements. By now, the contribution of a father who was committed to the care of his offspring had become a practical necessity:

"These encephalized early Homo species led to the emergence of early African Homo erectus after 2 Ma., the first hominin with body proportions like ours, bodies that were bigger and designed for walking not climbing (Wood and Collard 1999). Sexual size dimorphism had been reduced, largely because female H. erectus increased body size proportionately more than males (McHenry 1996). With female costs rising relative to males, significantly more co-operation by males with females can be expected from this time. But this is based on the prior evolution of inter-female co-operation." (2009, pp. 181-182)

In the fourth and final phase, with the emergence of Heidelberg man (who was as tall as we are and who had a brain capacity averaging around 1250 cc.), the human brain finally reached a size that fell within the modern range of 1000 to 1500 cc. The bigger brains of children placed an even greater load upon mothers, who would have been utterly unable to provide for their infants without the presence of a committed father. As Opie and Power put it:

"In the final phase of encephalization, from 500,000 years ago among H. heidelbergensis, female costs again rose steeply as mothers had to fuel the energy-hungry, larger brains of their offspring." (2009, p. 184)