|

|

In the same article, Professor Dawkins savagely castigates William Lane Craig for his willingness to justify "genocides ordered by the God of the Old Testament". According to Dawkins, "Most churchmen these days wisely disown the horrific genocides ordered by the God of the Old Testament" - unlike Craig, who argues that "the Canaanites were debauched and sinful and therefore deserved to be slaughtered." Dawkins then quotes William Lane Craig as justifying the slaughter on the grounds that: (i) if these children had been allowed to live, they would have turned the Israelites towards serving the evil Canaanite gods; and (ii) the children who were slaughtered would have gone to Heaven instantly when they died, so God did them no wrong in taking their lives. Dawkins triumphantly concludes:

Would you shake hands with a man who could write stuff like that? Would you share a platform with him? I wouldn't, and I won't. Even if I were not engaged to be in London on the day in question, I would be proud to leave that chair in Oxford eloquently empty.

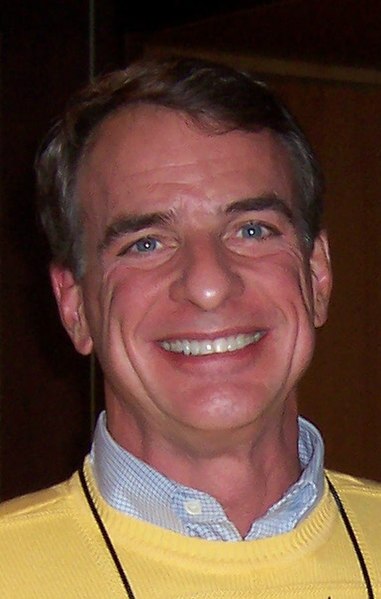

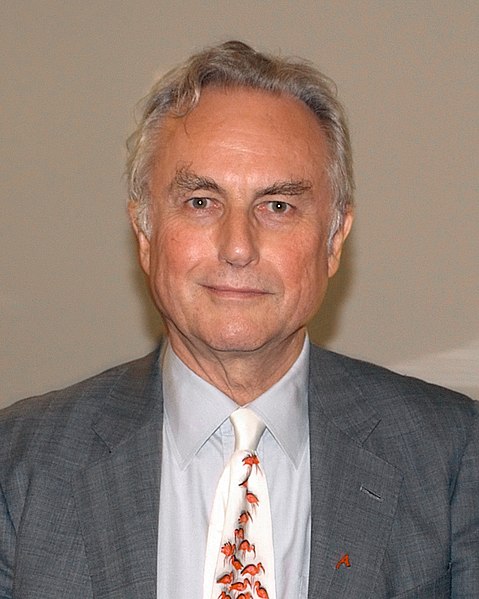

Professor Dawkins, allow me to briefly introduce myself. My name is Vincent Torley (my Web page is here), and I have a Ph.D. in philosophy. I'm an Intelligent Design proponent who also believes that modern life-forms are descended from a common ancestor that lived around four billion years ago. I'm an occasional contributor to the Intelligent Design Website, Uncommon Descent. Apart from that, I'm nobody of any consequence.

Professor Dawkins, I have ten charges to make against you, and they relate to apparent cases of lying, hypocrisy and moral inconsistency on your part. Brace yourself. I've listed the charges for the benefits of people reading this post.

|

My Ten Charges against Professor Richard Dawkins

1. Professor Dawkins has apparently lied to his own readers at the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science. In a recent post (dated 1 May 2011) he stated that he "didn't know quite how evil [William Lane Craig's] theology is" until atheist blogger Greta Christina alerted him to Craig's views in an article she wrote on 25 April 2011, when in fact, Dawkins had already read Professor Craig's "staggeringly awful" essay on the slaughter of the Canaanites and blogged about it in his personal forum (http://forum.richarddawkins.net), three years earlier, on 21 April 2008. In other words, Professor Dawkins' alleged shock at recently discovering Craig's "evil" views turns out to have been feigned: he knew about these views some years ago. 2. Professor Dawkins has recently maligned Professor William Lane Craig as a "fundamentalist nutbag" who isn't even a real philosopher and whose only claim to fame is that he is a professional debater, but his own statements about Craig back in 2008 completely contradict these assertions. Moreover, Dawkins' characterization of Craig as a "fundamentalist nutbag" is particularly unjust, given that Professor Craig has admitted that he's quite willing to change his mind on the slaughter of the Canaanites, if proven wrong. Although Professor Craig upholds Biblical inerrancy, he does so provisionally: he says it's possible that the Bible might be sometimes wrong on moral matters, and furthermore, he acknowledges that the Canaanite conquest might not have even happened, as an historical event. That certainly doesn't sound like the writings of a "nutbag" to me. 3. Professor Dawkins says that he refuses to share a platform with William Lane Craig, because of his views on the slaughter of the Canaanites, but he has already debated someone who holds substantially the same views as Craig on the slaughter of the Canaanites. On 23 October 1996, Dawkins debated Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, who also believes that the slaughter of the Canaanites was morally justified under the circumstances at the time (see here and here). What's more, in 2006, Dawkins appeared in a television panel with Professor Richard Swinburne, who holds the same view. Dawkins might reply that Swinburne did not make his views on the slaughter of the Canaanites public until 2011, but as I shall argue below, he can hardly make the same excuse about not knowing Rabbi Boteach's views. If he did not know, then he was extraordinarily naive. 4. Professor Dawkins refuses on principle to share a platform with William Lane Craig because of his views on the slaughter of the Canaanites, yet he is perfectly willing to share a platform with atheists whose moral opinions are far more horrendous: Dan Barker, who says that child rape could be moral if it were absolutely necessary in order to save humanity; Dr. Sam Harris, who says that pushing an innocent man into the path of an oncoming train is OK, if it is necessary in order to save a greater number of human lives; and Professor Peter Singer, who believes that sex with animals is not intrinsically wrong, if both parties consent. 5. Professor Dawkins refuses to share a platform with William Lane Craig, who holds that God commanded the Israelites to slaughter Canaanite babies whom He subsequently recompensed with eternal life in the hereafter. However, he is quite happy to share a platform with Professor P. Z. Myers, who doesn't even regard newborn babies as people with a right to life. (See here for P.Z. Myers' original post, here for one reader's comment and here for P. Z. Myers' reply, in which he makes his own views plain.) Nor does Professor Peter Singer, whom Dawkins interviewed back in 2009, regard newborn babies as people with a right to life. (See this article.) 6. Apparently Professor Dawkins himself does not believe that a newborn human baby is a person with the same right to life that you or I have, and does not believe that the killing of a healthy newborn baby is just as wrong as the act of killing you or me. For he sees nothing intrinsically wrong with the killing of a one- or two-year-old baby suffering from a horrible incurable disease, that meant it was going to die in agony in later life (see this video at 24:12). He also claims in The God Delusion (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2006, p. 293) that the immorality of killing an individual is tied to the degree of suffering it is capable of. By that logic, it must follow that killing a healthy newborn baby, whose nervous system is still not completely developed, is not as bad as killing an adult. 7. In his article in The Guardian (20 October 2011) condemning William Lane Craig, Professor Dawkins fails to explain exactly why it would be wrong under all circumstances for God (if He existed) to take the life of an innocent human baby, if that baby was compensated with eternal life in the hereafter. In fact, as I will demonstrate below, if we look at the most common arguments against killing the innocent, then it is impossible to construct a knock-down case establishing that this act of God would be wrong under all possible circumstances. Strange as it may seem, there are always some possible circumstances we can envisage, in which it might be right for God to act in this way. 8. Professor Dawkins declines to say whether he agrees with some of his fans and followers, who consider the God of the Old Testament to be morally equivalent to Hitler (see here and here for examples). However, the very comparison is odious, for in the same Old Testament books which Dawkins condemns, God exhorts the Israelites: "Do not seek revenge"; "Love your neighbor as yourself" and: "The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the LORD your God." (Leviticus 19:18, 33-34, NIV.) That certainly doesn't sound like Hitler to me - and I've personally visited Auschwitz and Birkenau. I wonder if Professor Dawkins has. 9. Dawkins singles out Professor William Lane Craig for condemnation as a "fundamentalist nutbag", but he fails to realize that Professor William Lane Craig's views on the slaughter of the Canaanites were shared by St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, John Calvin, the Bible commentator Matthew Henry, and John Wesley, as well as some modern Christian philosophers of eminent standing, such as Richard Swinburne, whom he appeared on a television panel with in 2006. Is he prepared to call all these people "nutbags" too? That's a lot of crazy people, I must say. 10. Unlike the late Stephen Jay Gould (who maintained that the experiment would be just about the most unethical thing he could imagine), Professor Dawkins believes that the creation of a hybrid between humans and chimps "might be a very moral thing to do", so long as it was not exploited or treated like a circus freak (see this video at 40:33), although he later concedes that if only one were created, it might get lonely (perhaps a group of hybrids would be OK, then?) Dawkins has destroyed his own moral credibility by making such a ridiculous statement. How can he possibly expect us to take him seriously when he talks about ethics, from now on?

|

Professor Dawkins, I understand that you are a very busy man. Nevertheless, I should warn you that a failure to answer these charges will expose you to charges of apparent lying, character assassination, public hypocrisy, as well as an ethical double-standard on your part. The choice is yours.

I would like to add that I have made every reasonable effort to substantiate my allegations against you, Professor, because a person's good name is a precious thing. I hope I haven't made any factual errors in what I've written below, but if I have mistakenly maligned you in any way, then I humbly and sincerely apologize, and shall of course retract my statements.

Without further ado, here are my ten questions for you.

|

Question 1. Why did you claim in a recent post (dated 1 May 2011) on your Weblog that you "didn't know quite how evil [William Lane Craig's] theology is" until atheist blogger Greta Christina alerted you to his views in an article she wrote on 25 April 2011, when in fact, you had already read Professor Craig's "staggeringly awful" essay on the slaughter of the Canaanites and blogged about it three years earlier, on 21 April 2008? Are you now willing to admit that you were lying?

|

Here are your exact words (21 April 2008) (which I have already emailed to several dozen people) on your official Website forum, at http://forum.richarddawkins.net/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=42300&p=831449#p831449:

Theological justification for genocide Part OnePostby Richard Dawkins » Mon Apr 21, 2008 8:22 am

http://www.reasonablefaith.org/site/News2?page=NewsArticle&id=5767One of our commenters on another thread, stevencarrwork, posted a link to this article by the American theologian and Christian apologist William Lane Craig. I read it and found it so dumbfoundingly, staggeringly awful that I wanted to post it again. It is a stunning example of the theological mind at work. And remember, this is NOT an 'extremist', 'fundamentalist', 'picking on the worst case' example. My understanding is that William Lane Craig is a widely respected apologist for the Christian religion. Read his article and rub your eyes to make sure you are not having a bad dream.

Richard

The link at http://www.reasonablefaith.org/site/News2?page=NewsArticle&id=5767 takes you straight to Professor William Lane Craig's essay on the slaughter of the Canaanites. The first atheist to blog about Craig's essay (as far as I know) was Professor Hector Avalos (see here) on August 24, 2007, shortly after it was written. On 16 January 2008, John Loftus blogged about Professor Craig's essay on his Weblog, Debunking Christianity, apparently after receiving a tip-off from atheist Ed Babinski. I know for a fact that the "atheist telegraph" is a pretty efficient one: scandalous news gets round very fast. So I was very suspicious when I read the following statement in a recent post (dated 1 May 2011) on your Weblog, Professor Dawkins, almost four years after Hector Avalos "outed" Professor Craig:

I have paid too little attention to Greta Christina, who has written some wonderful pieces on her blog. Here, for instance, is her splendid list of reasons why atheists have the right to be angry. And now (see below) she has a devastating expose of William Lane Craig, exploding the myth that he is a sophisticated 'theologian' rather than some fundamentalist nutbag. Or, actually, maybe it exposes the greater myth that there is such a thing as a sophisticated theologian at all. It is worth following the link to Craig's own post, which lays bare Craig's truly shocking Christian 'morality'. I knew he was over-rated, but I didn't know quite how evil his 'theology' is. It is even worse than the Richard Swinburne example (undeniably a 'sophisticated theologian'), which, as I quoted in The God Delusion, prompted Peter Atkins to expostulate, "May you rot in hell!"Richard

(Bold emphases mine - VJT.)

The four-year time delay between Craig's 2007 article, which was almost immediately picked up, by atheist Hector Avalos in 2007, and the date of your alleged discovery of Craig's post (1 May 2011), beggars belief, Professor. That time-lag was what prompted me to dig around, until I finally uncovered your April 2008 post on your personal forum site. That was the smoking gun.

Professor Dawkins, you stated in a blog post dated 1 May 2011 that you didn't know how evil Professor Craig's views were until Greta Christina wrote her "devastating expose", dated 25 April 2011. But you knew three years earlier, because you blogged about it on your debate forum on 21 April 2008! Your shocked reaction to Professor Craig's views was a feigned one.

You've been lying to your readers, haven't you, Professor? For what you say in your post of 21 April 2008 flatly contradicts what you later declared in your post of 1 May 2011. None of the several dozen people I contacted could think of a way of harmonizing the two statements either.

We've all lied at some stage in our lives, Professor. You have, I have, everyone has. But lying when attacking a man's character is another matter. You accused Professor William Lane Craig of being a "fundamentalist nutbag" who holds to an evil theology, and you savagely attacked "Craig's truly shocking Christian 'morality'." Telling a deliberate lie about what you knew while making such an accusation is a pretty silly thing to do, and it reduces your own moral credibility. I hope you will be enough of a gentleman to apologize for this ethical lapse on your next blog post.

Finally, Professor, I believe in giving credit where credit is due, so I would like to thank you for at least giving Professor Richard Swinburne the opportunity to reply to Peter Atkins' outburst against him, in a blog post on your Website, dated 16 December 2006. That was a decent and civilized thing to do. I hope you will extend the same courtesy to Professor Craig.

|

Question 2. Why have you characterized Professor William Lane Craig as a "fundamentalist nutbag" who isn't even a real philosopher and whose only claim to fame is that he is a professional debater, when your own statements on other occasions contradict these assertions? And how can you call Professor Craig a fundamentalist when Craig himself has said that he is willing to change his mind on the slaughter of the Canaanites, and even give up his belief in Biblical inerrancy, if he can be persuaded that God could never have issued such a command? Don't you owe Professor Craig an apology?

|

Professor Dawkins, in your latest article entitled, Why I refuse to debate with William Lane Craig, in The Guardian, you implied that William Lane Craig wasn't highly regarded as a philosopher:

Don't feel embarrassed if you've never heard of William Lane Craig. He parades himself as a philosopher, but none of the professors of philosophy whom I consulted had heard his name either. Perhaps he is a "theologian". For some years now, Craig has been increasingly importunate in his efforts to cajole, harass or defame me into a debate with him. I have consistently refused, in the spirit, if not the letter, of a famous retort by the then president of the Royal Society: "That would look great on your CV, not so good on mine".

And in The Intelligence^2 debate held at Wheaton College on November 29, 2009, when you were asked why you wouldn't debate William Lane Craig, you said that he was nothing more than a good debater:

I've always said, when I'm invited to do a debate, that I would be happy to debate a bishop, cardinal, Pope, an archbishop - indeed I have done both [the archbishops of Canterbury and York - VJT] - but that I don't take on creationists, and I don't take on people whose only claim to fame is that they are professional debaters. They've got to have something more than that. I'm busy.

Why, then, did you evince a higher opinion of Professor Craig's scholarly achievements in a post dated 21 April 2008 on your official Website forum, at http://forum.richarddawkins.net/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=42300&p=831449#p831449:

Theological justification for genocide Part OnePostby Richard Dawkins » Mon Apr 21, 2008 8:22 am

http://www.reasonablefaith.org/site/News2?page=NewsArticle&id=5767One of our commenters on another thread, stevencarrwork, posted a link to this article by the American theologian and Christian apologist William Lane Craig. I read it and found it so dumbfoundingly, staggeringly awful that I wanted to post it again. It is a stunning example of the theological mind at work. And remember, this is NOT an 'extremist', 'fundamentalist', 'picking on the worst case' example. My understanding is that William Lane Craig is a widely respected apologist for the Christian religion. Read his article and rub your eyes to make sure you are not having a bad dream.

Richard

(Bold emphasis mine - VJT.)

And I notice that the atheist blogger Greta Christina, whose article on Alter Net (One More Reason Religion Is So Messed Up: Respected Theologian Defends Genocide and Infanticide, 25 April 2011), criticizing Craig's theology was personally commended by you, in a post on your own Website, doesn't share your view that Professor Craig is a "fundamentalist nutbag". Here's what she wrote about him:

I want to make something very clear before I go on: William Lane Craig is not some drooling wingnut. He's not some extremist Fred Phelps type, ranting about how God's hateful vengeance is upon us for tolerating homosexuality. He's not some itinerant street preacher, railing on college campuses about premarital holding hands. He's an extensively educated, widely published, widely read theological scholar and debater. When believers accuse atheists of ignoring sophisticated modern theology, Craig is one of the people they're talking about.

Professor Dawkins, with the greatest respect, I think you owe Professor Craig a personal apology. It is one thing to call his views "evil". It is quite another thing to call him a "fundamentalist nutbag" and belittle his academic credentials when you know full well that he is a widely respected scholar.

Professor Dawkins, I would also call on you to publicly acknowledge that Professor William Lane Craig is not only a "widely read theological scholar", as you described him in 2008, but an accomplished philosopher as well. Want proof? Here's what his Website at Reasonable Faith says about him:

He has authored or edited over thirty books, including The Kalam Cosmological Argument; Assessing the New Testament Evidence for the Historicity of the Resurrection of Jesus; Divine Foreknowledge and Human Freedom; Theism, Atheism and Big Bang Cosmology; and God, Time and Eternity, as well as over a hundred articles in professional journals of philosophy and theology, including The Journal of Philosophy, New Testament Studies, Journal for the Study of the New Testament, American Philosophical Quarterly, Philosophical Studies, Philosophy, and British Journal for Philosophy of Science. (Emphases mine - VJT.)

A full list of Dr. Craig's numerous publications is available here.

Over thirty books and over a hundred articles? That's quite an impressive record. By comparison, Professor, you have written twelve books (a couple of which I currently possess - thank you), seventeen popular articles and thirty-three academic papers, according to the list of publications by Richard Dawkins at Wikipedia. On that basis, I'd have to say that Professor William Lane Craig is an even more prolific author than you are.

I haven't finished yet, Professor. What do leading atheist philosophers think of William Lane Craig? Here's what the American philosopher Quentin Smith, author (or co-author) of twelve books and over 140 articles, had to say about Professor Craig on page 183 of his essay, "Kalam Cosmological Arguments for Atheism" (in The Cambridge Companion to Atheism, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 9780521842709):

... [A] count of the articles in the philosophy journals shows that more articles have been published about Craig's defense of the Kalam [cosmological] argument than have been published about any other philosopher's contemporary formulation of an argument for God's existence.

If people write a lot about your arguments, that's a pretty reliable sign that you're highly respected in your field. By the way, the name "William Lane Craig" has 2,140 citations for articles (excluding patents) on Google Scholar.

Let me finish by citing excerpts from a letter to you written by Dr. Daniel Came, Lecturer in Philosophy, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Oxford, and dated 26 February 2011:

Dear Professor Dawkins,I write as an atheist and in reference to your refusal to participate in a one-to-one debate with the philosopher William Lane Craig...

I understand that you have also commented that 'a debate with Professor Craig might look good on his CV but it would not look good on mine'. On the contrary, the absence of a debate with the foremost apologist for Christian theism is a glaring omission on your CV and is of course apt to be interpreted as cowardice on your part.

Professor Dawkins, may I respectfully submit that if you, as an atheist, were going to debate just one philosopher on the topic of God's existence, Professor William Lane Craig would be a pretty logical choice.

Speaking of debates, Professor Dawkins, I'd like to comment on your policy of only debating senior clerics, such as bishops. May I respectfully point out that while bishops are traditionally regarded as teachers of the faith, that does not necessarily make them skilled at defending the faith in debate. Methinks you pick rather soft targets in debating bishops, Professor. Let me use an example from science to illustrate my point. As you know full well, the most effective debater on behalf of the theory of evolution by natural selection in the nineteeth century was not its founder, Charles Darwin, but a pugnacious naturalist named Thomas Henry Huxley, popularly known as Darwin's bulldog. Huxley fully appreciated that debating is not a gentle art. Most bishops don't.

How can you call Craig a "fundamentalist nutbag" if he's willing to change his mind?

Professor Dawkins, why do you paint Professor William Lane Craig as a "fundamentalist nutbag" for his views on the "horrific genocides ordered by the God of the Old Testament", when Craig's own words indicate that he is quite tentative, rather than dogmatic, in his views on the slaughter of the Canaanites? He admits that he might be wrong in his interpretation of the Bible, and he even admits the Bible itself might be wrong. Want evidence? Here it is, from the very article by Craig article by Craig which you cite:

So then what is Yahweh doing in commanding Israel's armies to exterminate the Canaanite peoples? It is precisely because we have come to expect Yahweh to act justly and with compassion that we find these stories so difficult to understand. How can He command soldiers to slaughter children?Now before attempting to say something by way of answer to this difficult question, we should do well first to pause and ask ourselves what is at stake here. Suppose we agree that if God (who is perfectly good) exists, He could not have issued such a command. What follows? That Jesus didn't rise from the dead? That God does not exist? Hardly! So what is the problem supposed to be? ...

The problem, it seems to me, is that if God could not have issued such a command, then the biblical stories must be false. Either the incidents never really happened but are just Israeli folklore; or else, if they did, then Israel, carried away in a fit of nationalistic fervor, thinking that God was on their side, claimed that God had commanded them to commit these atrocities, when in fact He had not. In other words, this problem is really an objection to biblical inerrancy.

In fact, ironically, many Old Testament critics are sceptical that the events of the conquest of Canaan ever occurred. They take these stories to be part of the legends of the founding of Israel, akin to the myths of Romulus and Remus and the founding of Rome. For such critics the problem of God's issuing such a command evaporates.

Now that puts the issue in quite a different perspective! The question of biblical inerrancy is an important one, but it's not like the existence of God or the deity of Christ! If we Christians can't find a good answer to the question before us and are, moreover, persuaded that such a command is inconsistent with God's nature, then we'll have to give up biblical inerrancy. (Emphases mine - VJT.)

Note that in this passage, Professor Craig is prepared to entertain the possibility that the Bible may contain errors not only of fact (Did the conquest of Canaan take place?) but also regarding morality (Did God really command the Israelites to slaughter the innocent?)! Does that sound like the ravings of an "fundamentalist nutbag" to you?

Incidentally, the above quote utterly refutes the polemic directed at Professor Craig by atheist blogger Greta Christina (One More Reason Religion Is So Messed Up: Respected Theologian Defends Genocide and Infanticide, April 25, 2011) towards the end of her article:

When your holy book says that God ordered his chosen people to slaughter an entire race, down to the babies and children -- and you insist that this book is special and perfect -- you put yourself in the position of defending genocide....And you can't cut the Gordian knot. You can't simply say, "This is wrong. This is vile and indefensible. This kind of behavior comes from a tribal morality that humanity has evolved beyond, and we should repudiate it without reservation."

Not without relinquishing your faith.

But as we've seen, Professor Craig is prepared to jettison the doctrine of Biblical inerrancy, if he can be convinced that God could never have justly issued a command to kill the Canaanites. He is not tied to committing genocide; he himself says that he would continue to believe in the Resurrection and the Divinity of Christ even if the Bible were proved wrong about the slaughter of the Canaanites.

Why do you care about Craig's views regarding a one-off set of events which Craig himself acknowledges might not have even happened?

Professor Dawkins, if you have a look at William Lane Craig's article, you'll see that he has reservations about the historicity of the Israelite conquest of Canaan. That's because at the present time, there is no good archaeological evidence for such a conquest. If there was no Israelite conquest of Canaan, then no Canaanite babies were ever slaughtered and no Canaanite women were ever killed.

Even if such an event did take place, it happened around 3,300 years ago, and Professor Craig himself acknowledges that a Divine command to kill could no longer be given to us today (see this video at 30:52). Thus its modern practical relevance is absolutely zero.

Why, then, are you taking such a principled stance regarding William Lane Craig's views about an event that happened (if it happened), about 3,300 years ago? I find this puzzling, Professor Dawkins. Would you care to explain?

Finally, here is a list of atheists who have debated Professor William Lane Craig on the topic of "Does God exist?" or "Atheism vs. Christianity" in the past: Frank Zindler, Keith Parsons, Eddie Tabash, Paul Draper, Peter Atkins, Garrett Hardin, Anthony Flew, Theodore Drange, Quentin Smith, Michael Tooley, Douglas Jesseph, Corey Washington, Massimo Pigliucci, Edwin Curley, Ron Barrier, Victor Stenger, Brian Edwards, Peter Slezak, Austin Dacey, Bill Cook and John Shook.

If William Lane Craig was a good enough debating opponent for these atheists, then why wasn't he good enough for you, Professor Dawkins?

|

Question 3. Why do you refuse to share a platform with William Lane Craig for his views on the slaughter of the Canaanites, when on 23 October 1996, you debated the Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, who also believes that the slaughter of the Canaanites was morally justified? Lastly, Professor, do you consider Orthodox Jews who share Rabbi Boteach's views (as many do) to be beyond the pale of civilized debate, and would you shun them in a debating forum, just as you have shunned Professor William Lane Craig?

|

Few people in the Jewish community have publicly condemned religious violence so consistently as Rabbi Shmuley Boteach. Indeed, in an April 2009 article in The Huffington Post, Rabbi Boteach vehemently denounced the actions of Baruch Goldstein, a religious terrorist who killed twenty-nine worshippers at a mosque. Boteach wrote:

[A]ny Rabbi who was to praise a Jewish murderer would be fired from his post and banished from his community. The Torah is clear: 'Thou may not murder' (Exodus 20) and 'Thou shalt not take revenge' (Leviticus 19).

Such is Rabbi Boteach's loathing of terrorism that he believes there should be a death penalty for acts of terrorism. And yet Rabbi Shmuley Boteach also believes that the slaughter of the Canaanites was a necessary, one-off act which was morally justified because of the very extreme situation in which Israel found itself. For in the article in The Huffington Post I quoted from above, which was entitled, Christopher Hitchens and the Killer Jews (April 1, 2009), Rabbi Boteach responded to charges by Christopher Hitchens, that the story in Numbers 31 of how Moses commanded the Jews to slaughter the Midianites was being used by religious settlers in Israel in order to justify acts of religious terrorism. Boteach explained the story as follows:

Second, no Biblical story of massacre, which is a tale and not a law, could ever be used to override the most central prohibition of the Ten Commandments and Biblical morality.Murder is the single greatest offense against the Creator of all life and no Jew would ever use a Biblical narrative of war or slaughter as something that ought to be emulated. In our time Churchill and Roosevelt, both universally regarded as moral leaders and outstanding men, ordered the wholesale slaughter of non-combatants in the Second World War through the carpet- bombing of Dresden, Hamburg, Berlin, and Tokyo. Truman would take it further by ordering the atomic holocaust of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. How did men who are today regarded as righteous statesmen order such atrocities? They were of the opinion that only total war could end Nazi tyranny and Japanese imperial aggression. They did it in the name of saving life. Which is of course not to excuse their actions but rather to understand them in the context of the mitigating circumstances of the time. I do not know why Moses would have ordered any such slaughter even in the context of war. But I do know that the same Bible who relates the story also expressly forbids even the thought of such bloodshed ever being repeated.

Evidently Rabbi Boteach views that slaughter of the Canaanites as a violent but necessary act, which was never to be repeated.

Rabbi Boteach defended the same views in a transcript of the debate between him and Christopher Hitchens on January 30, 2008. Here is what Rabbi Shmuley Boteach said in that debate, in response to Christopher Hitchens' challenge, "And I ask again, what happened to the Amalekites, what happened to the Midianites if this fiction is all that it is?" Hitchens was referring to nations that were slaughtered by the Israelites about 3,300 years ago. Boteach replied:

BOTEACH: I lived in Britain for eleven years and it's a country that I came to love and admire. I had the great honor of being the rabbi at Oxford University. And I befriended people like Richard Dawkins, who became a dear friend, and in England, until today, the statesman who is most respected is Winston Churchill. I think that's fair to say, statistically, popularity. He ordered the indiscriminate bombing of Dresden, Hamburg, these cities were obliterated three months before the war ended. In Dresden 250,000 died, in Hamburg 330,000 died, there were cyclones created by the fire bombs, winds 200 miles per hour from the fires. Four months later Harry S. Truman, who was voted our second-most popular president of the twentieth century, ordered the indiscriminate nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But this did not mean that these were immoral men. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was voted the most popular, the most effective of twentieth century presidents, he participated in many of those decisions for the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians including men, women and children. It's just that they found...GILLMAN: Rabbi Boteach, what does this have to do with God?

BOTEACH: I'm sorry? I'm answering his thing about the Hittites. It's just that they felt that certain war measure sometimes called for very, very extreme measures that, in any other context, would be immoral. Judaism would never today allow the murder of Hittites, Amalekites. In fact, Christopher Hitchens it was only done in the context of war at the time and God specifically forbade it forever thereafter in the same way that we would never bomb a German city today or use a nuclear bomb against another nation. You know that [audience disapproval] well I don't think we would. Maybe the United States would nuke someone, then so be it, I don't believe we would. I should tell you that Christopher Hitchens writes in his book that rabbis debate whether the Palestinians are today the Amalekites and that is why they ought to be and debate whether they should be expelled. Again, name a single mainstream rabbi there's always fringes and to the extent to which fringes are kept on the fringe they could never ever define the mainstream name any mainstream rabbi that would ever say that. In fact, every Orthodox Jew, or anyone who's knowledgeable with the Torah here will know, that we are not that Amalek is a concept that we have no capacity to identify, according to the Torah itself. We don't know who they are. It's an ethereal concept, so much so that when the Jews of Hevron [audience laughs at Gillman blowing his nose] when Baruch Goldstein killed the Palestinians who were at prayer in their mosque, the very next morning, Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sachs I was living in England called it an abomination as did virtually every other rabbi. My house was firebombed that night at Oxford. (Until today the police don't know by who.) Thank God a Spanish au pair who lived with us saved our childrens' lives by putting it out. (My wife and I were out it was a Saturday night, it was the night after Purim if you recall.) I still got up I called a press conference and I said that what Baruch Goldstein did to those Palestinians who are our brothers, who are equally God's children, is the highest disgrace that Judaism, an Orthodox jury, has faced in my lifetime. So let's never say that this is justified and that's why, I mean, with all due respect, in my own opinion, if you're going to write a bookand you're a great scholar, and I love your writing, most of the time and if you're going to say that "Rabbis say this and this court said that," I really believe there ought to be a footnote or a name. Until today and you're still not quoting a name, you're quoting a book of something, etc. (There is no such thing as a high Jewish court in Halakha, by the way.)

Professor Dawkins, you debated Rabbi Boteach back in 1996 - a fact which you've acknowledged in an article entitled, Richard Dawkins Responds to Rabbi Shmuley Boteach (16 May 2008). Here is what Wikipedia says about his early years:

Rabbi Shmuley Boteach received his rabbinic ordination in 1988 from the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement in New York City, and was sent as a Chabad-Lubavitch shaliach (emissary) to become its representative for a student group in the city of Oxford in England, where he founded the L'Chaim Society.

Professor Dawkins, you personally knew Rabbi Boteach at Oxford. I presume, then, that you knew when you debated Rabbi Boteach in 1996 that someone from the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement would take his Bible pretty literally, and who would therefore, if asked for his views, defend the slaughter of the Canaanites and the Amalekites as an act of violence which was regrettable but necessary, at the time in which it occurred.

In 1996, you debated a Rabbi who, like Professor William Lane Craig, held that the slaughter of the Canaanites was an extremely violent but morally justifiable act, given the circumstances of the time, but that this act should never be repeated in the future. Why, then, did you refuse to debate Professor Craig, while agreeing to debate the Rabbi? Either your ethical standards are inconsistent, or you were extraordinarily naive and you really didn't realize that Rabbi Boteach would hold such views. Which is it?

By the way, Professor, you might like to read what Chabad.org says about the slaughter of the Amalekites in the article, War with Amalek. Here's an excerpt:

One day Samuel came to the king with the demand from G-d to wage war against Amalek and destroy it completely. Without any provocation Amalek had attacked and inflicted untold suffering on the Jews while the latter were wandering in the desert on their way from Egypt. Fearing to attack the Jews openly, they had sniped sporadically at the weaker and less defended points of the line of march. G-d had therefore commanded that when Israel was settled on their land, Amalek was to be annihilated.Now the time had come. Saul was told to show no pity. Nothing was to remain of the entire nation and all its wealth, for as long as there were any Amalekites alive, there could be no peace for Israel. For Amalek was the incarnation of all evil.

Professor Dawkins, you have repeatedly condemned what you call "the genocide of the God of the Old Testament". You also tell us in your article that you have publicly engaged with Britain's Chief Rabbi on the topic of God's existence. You must be aware, however, that many (but not all) Orthodox rabbis uphold a fairly literal view of the Bible: in particular, they believe that the words of the Torah (the first five books of the Bible) were spoken to Moses by God. That includes the stories of God's commanding Moses to wipe out the Canaanites and other peoples, which were traditionally regarded by the rabbis as valid for their time (after certain conditions had been satisfied), but no longer applicable after the end of the first century A.D., since the peoples who were originally targeted were no longer identifiable (see here and here).

So I'd like to ask you, Professor: would you be willing to debate the topic of God's existence with an Orthodox Jewish rabbi holding such a view? Would you be prepared to look a rabbi in the eye and tell him, "Your God is a genocidal monster"? Or do you also consider rabbis holding such views to be beyond the pale of civilized debate, and would you shun them as you have shunned Professor Craig?

|

Question 4. Why do you refuse to share a platform with William Lane Craig for his views on the slaughter of the Canaanites, when you are perfectly willing to share a platform with atheists who defend such practices as child rape (Dan Barker) and pushing innocent people into the paths of oncoming trains (Dr. Sam Harris) if they are performed in order to save human lives, and with atheists who believe that sex with animals is not intrinsically wrong if both parties consent (Peter Singer)?

|

The extreme views of Dan Barker and Dr. Sam Harris

Let me emphasize that although I regard Barker's and Harris' moral principles as fundamentally bent, I am quite sure that Dan Barker and Dr. Sam Harris are likeable people in real life. However, the issue here is one of consistency. If you condemn Craig, you have to condemn Barker and Harris as well.

Dan Barker: Child rape could be moral in extreme situations, in order to save humanity

If you would like to see proof of the depravity of Dan Barker's moral principles, please have a look at the following Youtube video:

Atheist Dan Barker Says Child Rape Could Be Moral in Extreme Situations, in Order to Save Humanity.

The scenario Barker is considering here is one where an evil and technologically advanced alien says he'll destroy humanity if you don't rape a child. Because Barker is an act utilitarian, he says he would comply with the alien's request, although to his credit, he admits that he'd hate himself for doing so. I have to say I was deeply impressed with Dan Barker's intellectual honesty and his obvious aversion to the idea of performing such a hideous deed. Nevertheless, his moral principles are perverse if they lead him to adopt the conclusion that child rape could be moral in an extreme situation.

The problem with Barker's moral principles is that utilitarianism makes the greatest good of the greatest number its supreme good. Once you accept that premise, then the rape of a child becomes less important by comparison. In extreme circumstances, it might even be morally necessary, in order to promote the greatest good of the greatest number.

You can say what you like about Yahweh, the God of ancient Israel, Professor Dawkins, but I don't think even you would accuse Him of sanctioning child rape. Professor William Lane Craig adheres to a Divine Command theory of ethics, but he also holds that God's commands are grounded in His nature, which is essentially good and loving. On Craig's view, God could justly command the taking of an innocent human life, as life is a gift which belongs to Him - and in addition, the very act of taking such an innocent person's life is also that person's doorway to eternal life and happiness with God. But it is inconceivable that the God worshiped by Professor Craig could command the rape of a child. Such an act cannot, from even a God's-eye perspective, be described as a good or loving act.

You've posted an interview given by Dan Barker with Fox News on your Website, so I take it you don't regard his views as beyond the pale. Why, then, do you refuse to sit down with Professor William Lane Craig and talk about the existence of God?

[Update by VJT: Since I posted this, some of my readers have responded along the following lines: "Dan Barker is talking about the rape of just one child. Don't even try to compare that to genocide." I'd like to make two points in reply:

1. Morality isn't about numbers, or overall results. It's about attitudes - one's state of heart and mind, as the Dalai Lama so perceptively put it in his Ethics for the New Millennium. An action is not good or bad because of its results, but because of the attitudes underlying it. If you want to assess how evil someone is, ask yourself this: "What's the worst thing he would be prepared to do to me?" That's what's so horrifying about the act utilitarianism embraced by Barker and Harris. There isn't anything that consistent act utilitarians wouldn't do, in order to promote the greatest happiness of the greatest number. They would be prepared to inflict unlimited degradation on an individual, for that purpose. Degradation of an individual e.g. through torture or rape can be an even more profound insult against human dignity than killing them. There are certain things that the God of the Old Testament would never do to people. He never commands torture. He orders dead bodies to be buried by sundown. He forbids bestiality. Why? Because we are all made in His image. Even when He destroys people, He does not degrade them. If I had a choice between living in an Israelite theocracy and a society governed by act utilitarian principles, I know which one I'd choose. The worst fate that could happen to me in the former society is that I'd be killed. In the latter society, I might be tortured, drugged, degraded and brainwashed. That's far worse.

2. In any case, Barker's act utilitarianism has much more horrific implications than he apparently realizes. What if the evil alien in Barker's example commanded people to rape and brutalize children repeatedly, over a period of years, and also said that he would destroy humanity if everyone didn't comply? On Barker's logic people would have to comply. It gets worse. What if the evil alien commanded people to do this to all the children, and then finally kill them, and do the same to all the adults, except for a few who would be left alive and allowed to breed in peace and have a very large number of descendants? If you were to take the interests of future generations into account - as global warming activists insist we should - then the interests of the vast number of descendants would outweigh the suffering endured by the 99.9% of the human race that would get tortured and killed, in order to save the human race. Torturing and killing off 99.9% of the human race is even worse than genocide - and yet, Professor Dawkins, you regard Barker's act utilitarianism (which would justify this behavior when taken to its logical conclusion), as a legitimate point of view, while rejecting Professor William Lane Craig's ethics as beyond the pale. I have to say: that's ethically inconsistent.

End of update - VJT.]

Dr. Sam Harris and the Fat Man

Dr. Sam Harris outlines his moral views on some controversial cases here:

Dr. Harris is also the author of a book on ethics, which was reviewed by Dr. Joseph Bingham in an article entitled, The Science of Bad Philosophy: A Review of Sam Harris' book, The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values.

However, what I find most shocking about Sam Harris' ethical views is not his position on torture in the ticking time bomb scenario, which many people might agree with, or even his willingness to launch a preemptive nuclear war in order to prevent an imminent attack from a fanatical government, but his view on the famous "Fat Man" case, which goes like this.

Imagine that you see a trolley which is about to hit and kill five people. The only way to stop it is to push the fat man in front of you to block the trolley.

Nearly everyone, if you ask them, says it would be wrong to push the fat man. Dr. Harris would push the fat man onto the track. I have to say that I cannot understand how anyone could do that. I think Dr. Harris displays a badly formed moral conscience in defending such an action, and I'm sure the vast majority of my readers would agree with me. And I'm happy to see that you agree with me too, Professor Dawkins. The evil of the action defended by Sam Harris is self-evident; it needs no further commentary.

To render his view more plausible, Sam Harris likens the action of pushing the fat man onto the track to the famous "Trolley problem". The error in Harris' moral reasoning has been identified by an atheist who goes under the pen name of Robephiles, in an article entitled, Sam Harris and the Moral Failure of Science. Robephiles sharply criticizes Harris' ethical views, and regards them as being "as dangerous as even the most radical religion":

In one of his speeches Harris mentions the famous "trolley problem." In one scenario a runaway trolley is on a track and going to run over four people but you can flip a switch and put it on the other track where another person is. In the second scenario you are standing next to a fat man who you can push in front of the trolley to save the four people. In the first case almost everyone says pulling the switch is okay but almost nobody says pushing somebody in front of the trolley is okay. Harris mentions this but doesn't even have a point. He just says that the two acts are "different" but doesn't clarify.If he had bothered to think about it for even a second he would have seen that the first example is collateral damage. There was no malice in the flipping of the switch but it was the act that was necessary to save the four. If the other person was to see the trolley and jump out of the way then their death would not be necessary. In the case of the man being pushed in front of the trolley we are using another human being as a means to an end and that is unacceptable to most of us. (Italics mine - VJT.)

Unlike Dan Barker, Dr. Harris seems to have no qualms about his choice. He seems to believe that if you don't see things his way, then you're simply irrational. Rational, enlightened people would evaluate the morality of such an act by looking at the results produced.

What's missing from Dr. Harris' equation? Atheist blogger Robephiles hits the nail on the head: Harris doesn't regard human beings as "ends in themselves", properly speaking:

He [Sam Harris] doesn't see what else is important other than the maximizing of human welfare, so your religious rights don't matter, your civil rights don't matter, due process doesn't matter. Kant claimed that every human being had intrinsic value and an inherent right to be free. Kant thought that it was better to let humans be free to make bad choices than to enslave them in the interest of their well-being. For the last few hundred years civilizations that have lived by these principles have done pretty well.

For Harris, while treating people as "ends in themselves" in everyday life might be a good way to safeguard human well-being in the majority of cases, in the end, overall "human well-being" is the supreme good, and human lives can be sacrificed to protect this greater good.

William Lane Craig, on the other hand, says that no human being has the authority to take an innocent human life. Such an action is tantamount to "playing God". Now, Craig, like Harris, is not a Kantian, but at least the God worshiped by Craig is an essentially loving God, who cares about the welfare of each and every one of us, as individuals.

So here's my question, Professor Dawkins. Why do you regard William Lane Craig's views as beyond the pale when he maintains that God can justly take the life of an innocent baby, so long as the baby is compensated with eternal life in the hereafter, but not the views of Dan Barker and Sam Harris, who argue that practices as child rape (Dan Barker) and pushing innocent people into the paths of oncoming trains (Dr. Sam Harris) are morally justifiable if they are necessary in order to save human lives?

Bestiality is not intrinsically immoral, according to Professor Peter Singer

Peter Singer has to be one of the most consistent philosophers alive today. He is a proponent of preference utilitarianism who gives away one-quarter of his income and practices vegetarianism (in fact, he is a virtual vegan). His views on infanticide are fairly well known: he believes that newborn babies are not persons, and that the killing of a severely disabled newborn infant is not wrong - views critiqued by Scott Klusendorf in his article, Peter Singer's Bold Defense of Infanticide. Not so well-known is the fact that Professor Peter Singer believes that sex with animals is not intrinsically wrong, if both parties consent. This belief is a logical consequence of Singer's utilitarianism.

Here is what Peter Singer says in his infamous article, Heavy Petting:

On the one hand, especially in the Judeo-Christian tradition - less so in the East - we have always seen ourselves as distinct from animals, and imagined that a wide, unbridgeable gulf separates us from them. Humans alone are made in the image of God. Only human beings have an immortal soul. In Genesis, God gives humans dominion over the animals. In the Renaissance idea of the Great Chain of Being, humans are halfway between the beasts and the angels. We are spiritual beings as well as physical beings. For Kant, humans have an inherent dignity that makes them ends in themselves, whereas animals are mere means to our ends. Today the language of human rights rights that we attribute to all human beings but deny to all nonhuman animals maintains this separation.On the other hand there are many ways in which we cannot help behaving just as animals do or mammals, anyway and sex is one of the most obvious ones. We copulate, as they do. They have penises and vaginas, as we do, and the fact that the vagina of a calf can be sexually satisfying to a man shows how similar these organs are. The taboo on sex with animals may, as I have already suggested, have originated as part of a broader rejection of non-reproductive sex. But the vehemence with which this prohibition continues to be held, its persistence while other non-reproductive sexual acts have become acceptable, suggests that there is another powerful force at work: our desire to differentiate ourselves, erotically and in every other way, from animals...

[S]ex with animals does not always involve cruelty. Who has not been at a social occasion disrupted by the household dog gripping the legs of a visitor and vigorously rubbing its penis against them? The host usually discourages such activities, but in private not everyone objects to being used by her or his dog in this way, and occasionally mutually satisfying activities may develop...

At a conference on great apes a few years ago, I spoke to a woman who had visited Camp Leakey, a rehabilitation center for captured orangutans in Borneo run by Birute Galdikas, sometimes referred to as "the Jane Goodall of orangutans" and the world's foremost authority on these great apes. At Camp Leakey, the orangutans are gradually acclimatised to the jungle, and as they get closer to complete independence, they are able to come and go as they please. While walking through the camp with Galdikas, my informant was suddenly seized by a large male orangutan, his intentions made obvious by his erect penis. Fighting off so powerful an animal was not an option, but Galdikas called to her companion not to be concerned, because the orangutan would not harm her, and adding, as further reassurance, that "they have a very small penis." As it happened, the orangutan lost interest before penetration took place, but the aspect of the story that struck me most forcefully was that in the eyes of someone who has lived much of her life with orangutans, to be seen by one of them as an object of sexual interest is not a cause for shock or horror. The potential violence of the orangutan's come-on may have been disturbing, but the fact that it was an orangutan making the advances was not. That may be because Galdikas understands very well that we are animals, indeed more specifically, we are great apes. This does not make sex across the species barrier normal, or natural, whatever those much-misused words may mean, but it does imply that it ceases to be an offence to our status and dignity as human beings.

Professor Peter Singer wrote these words back in 2000, and I presume you were familiar with his background, Professor Dawkins, when you interviewed the man for 43 minutes in June 2009, and even posted the interview on your Website!

Professor Dawkins, I put it to you that it is ethically inconsistent to declare Professor William Lane Craig's views beyond the pale, and then interview a man who can see nothing intrinsically wrong with bestiality.

[Update by VJT: Utilitarian readers who fail to see the connection between bestiality and genocide might like to consider these facts. Some scientists claim that human activities will result in the extinction of a large number of animal species - perhaps as many as 40% - over the next few hundred years. Let's suppose for argument's sake that they're right. Professor Peter Singer insists on his article on bestiality that the dignity of a human being is comparable with that of an animal. If the dignity of a human being is different only in degree from that of any other sentient animal, then on strictly utilitarian grounds, it could be argued that it would be better if the entire human race were to die out, in order that the Earth's biosphere should be saved. After all, the other animals outnumber us. Now ask yourself what some eco-activists who are motivated by utilitarianism might be prepared to do, in the name of protecting "Mother Earth". I think you can all see where I'm going here: utilitarianism has far more diabolical potential implications than the Christianity espoused by Professor Craig.]

|

Question 5. Professor Dawkins, why do you object to sharing a platform with someone who believes that God could have justly ordered the destruction of innocent Canaanite children provided that they were recompensed in the hereafter, when you are quite happy to share a platform with Professor P. Z. Myers, who doesn't even regard newborn babies as people with a right to life? Finally, will you please publicly dissociate yourself from comments made by P. Z. Myers, in which he referred to Professor William Lane Craig as an "amoral bastard" and a "nasty, amoral excuse for a human being"? And are you willing to dissociate yourself from the views of Professor P. Z. Myers and Professor Peter Singer, that newborn babies are not persons with a right to life, and that killing a healthy newborn baby is not as bad as killing a healthy adult?

|

It would surely be hypocritical to object to sharing a platform with someone who tentatively believed that God could have justly ordered the destruction of a group of human beings (including even children) in the land of Canaan some 3,300 years ago, provided that the innocent children were recompensed in the hereafter, while at the same time being happy to share a platform with someone who doesn't regard newborn babies as people. In that case, what do you have to say about the views of Professor P. Z. Myers, who is one of the 25 most influential living atheists?

Professor Myers is on record as saying that he doesn't believe that newborn babies are fully human, and he makes it clear that he doesn't regard them as persons, either. Professor P. Z. Myers made these utterances in a comment on one of his posts a few months ago. (See here for P.Z. Myers' post, here for one reader's comment and here for P. Z. Myers' reply, in which he makes his own views plain.) So, what exactly did P. Z. say? In response to a reader who claimed that there is one very easily defined line between personhood and non-personhood - namely, birth - P. Z. Myers replied:

Nope, birth is also arbitrary, and it has not been even a cultural universal that newborns are regarded as fully human.I've had a few. They weren't.

Let me state for the record that I have no doubt that Professor P. Z. Myers is an excellent father; but that is not the issue here. His views on newborn babies are the issue. Why are you in high dudgeon over the views of Professor William Lane Craig regarding an event in the Middle East which may or may not have even happened, some 3,300 years ago, despite the fact that Professor Craig believes that newborn infants are people like you and me, while at the same time, the views of Professor Myers don't appear to bother you? You were happy to appear with him at an event organized by the British Humanist Association on 9 June 2011 (see here for podcast).

Professor Dawkins, I respectfully submit that you are guilty of an ethical double standard here.

Finally, I'd like to draw your attention to the following blog comments by P. Z. Myers:

Standing up to William Lane Craig (20 October 2011):

I was pleased to see that one of Dawkins' points was one that is not made often enough: William Lane Craig is a nasty, amoral excuse for a human being.

Wait, I thought they believed in an absolute morality? (30 April 2011):

I don't trust that amoral bastard.

Curiously, Professor P. Z. Myers goes on to say: "I don't think William Lane Craig is an intrinsically evil human being." Go figure.

Professor Dawkins, will you agree that P. Z. Myers was wrong to call Professor William Lane Craig an "amoral bastard", and will you publicly dissociate yourself from Professor Myers' remarks?

Professor Peter Singer, whom you interviewed back in 2009, is another leading atheist who does not regard newborn babies as people with a right to life. Once again, I have to ask: why do you regard Craig's views on newborn babies as beyond the pale, but not Singer's?

|

Question 6. Professor Dawkins, you have stated that you see nothing intrinsically wrong with the killing of a one- or two-year-old baby suffering from a horrible incurable disease, that meant it was going to die in agony in later life (see this video at 24:12). Do you believe that: (i) a newborn human baby is a person with the same right to life that you or I have, and do you believe that: (ii) the killing of a healthy newborn baby is just as wrong as the act of killing you or me? If not, then aren't your views far more unconscionable than those of Professor William Lane Craig, who believes that an innocent human baby is a person with the same right to life that you or I have, but that God can justly take its life, so long as it is compensated with eternal life in the hereafter?

|

You see, Professor Dawkins, I'm quite sure that Professor William Lane Craig would answer in the affirmative to parts (i) and (ii) of my question, despite his eccentric views about what God can and cannot command people to do. And I believe that he would be quite within his rights in refusing to share a platform with someone who didn't believe that newborn babies were persons with the same right to life as everyone else, and that killing a newborn baby is just as bad as killing an adult. For people who reject these views, which Western civilization has firmly believed for almost 2,000 years, really are beyond the pale, morally speaking.

I'm not sure what your views on babies really are, Professor Dawkins, but it sounds to me like you don't believe that newborn babies are persons with the same right to life as everyone else. I very much hope I am wrong, but I have two reasons for suspecting that you think this way.

The first reason is your statement that you see nothing intrinsically wrong with the killing of a one- or two-year-old baby suffering from a horrible incurable disease, that meant it was going to die in agony in later life. I appreciate your concern to end individuals' suffering, Professor, but the fact that:

(a) you thought killing was not wrong up to the age of one or two;

(b) you spoke not of present suffering on the baby's part, but of future agony that it would die from later in life; and

(c) you didn't attach any conditions relating to the baby's intelligence,

makes me think that you regard it as OK to end the life of an intellectually normal baby too, with a horrible incurable disease that meant it was going to die in agony in later life. That can only mean that you don't regard a baby as a person with a right to life, before the age of one or two. Am I interpreting you correctly, Professor, or am I misreading you?

My second reason is the following quote, which is taken from your book, The God Delusion (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2006):

A consequentialist or utilitarian is likely to approach the abortion question in a very different way, by trying to weigh up suffering. Does the embryo suffer? (Presumably not if it is aborted before it has a nervous system; and even if it is old enough to have a nervous system it surely suffers less than, say, an adult cow in a slaughterhouse.) Does the pregnant woman, or her family, suffer if she does not have an abortion? Very possibly so; and, in any case, given that the embryo lacks a nervous system, shouldn't the mother's well-developed nervous system have the choice?This is not to deny that a consequentialist might have grounds to oppose abortion. 'Slippery slope' arguments can be framed by consequentialists (though I wouldn't in this case). Maybe embryos don't suffer, but a culture that tolerates the taking of human life risks going too far: where will it all end? In infanticide? The moment of birth provides a natural Rubicon for defining rules, and one could argue that it is hard to find another one earlier in embryonic development. Slippery slope arguments could therefore lead us to give the moment of birth more significance than utilitarianism, narrowly interpreted, would prefer. (p. 293) (Emphases mine VJT.)

I don't wish to talk about abortion in this post, Professor Dawkins. The topic we're discussing here is infanticide. However, I noticed that in the passage above, you claim that the immorality of killing an individual is tied to the degree of suffering it is capable of. By that logic, it must follow that killing a newborn baby, whose nervous system is still not completely developed, is not as bad as killing an adult.

I also notice that you compare human embryos with those of cows and sheep, which seems to suggest that you would regard the worth of a newborn human baby as differing only in degree from that of a newborn baby calf or lamb.

Finally, I interpret your later remarks on the slippery slope and on birth as "a natural Rubicon for defining rules" (italics mine) as meaning that you thinks it would be prudent for the law to treat babies as having a right to life from babies, to avoid far worse consequences that would result if they weren't recognized as having rights, but that in fact, you do not believe that a newborn baby has a natural right to life; nor do you believe that killing a newborn baby is as bad as killing an adult.

Am I right, Professor Dawkins? I sincerely hope that you will tell me I am wrong, for I would be deeply saddened to think that you hold such views about newborn babies. Actually, I asked you several months ago, and even emailed you, but unfortunately I did not receive a reply, and it is quite possible that my email did not reach you personally. (I realize you're a busy man, and that you have staff who handle emails sent your way.) So I'm giving you the chance to reply now. Have I misinterpreted you?

|

Question 7. Professor Dawkins, could you please explain exactly why it would be wrong for God (if He existed) to take the life of an innocent human baby, if that baby was compensated with eternal life in the hereafter? Given that you regard Professor Craig's views as obviously wrong, this should be an easy question for you to answer.

|

Please select the answer that best matches your view.

(a) It's always wrong for any individual (including God) to kill an innocent baby for fun, or on a whim.

(b) It's always wrong for any individual (including God) to intentionally take the life of an innocent human being for any reason - even if the individual is compensated with eternal life in the hereafter. Killing an innocent human being violates the Golden Rule: do as you would be done by.

(c) It's always wrong for any individual (including God) to treat an innocent human being as a means to some higher end.

(d) It's always wrong for any individual (including God) to knowingly cause extreme pain and distress to an innocent human being, in the process of intentionally taking its life. (The case of pain suffered by a child during emergency surgery is morally different, because that's a life-preserving act.)

(e) I can't prove it's wrong in all possible cases, but even if there were special circumstances in which it might be right for God to take an innocent baby's life, it would never be right for Him to command us to do so. If He had to do such a terrible thing for some pressing reason, He should do the dirty work Himself.

OK, now it's time for some thought experiments. I realize they're pretty far-out, so please bear with me.

If you chose (a), then it seems you would concede that it might be all right (in principle) for the omniscient Being to kill an innocent baby for a grave reason. "What kind of reason?" I hear you ask. See the next paragraph.

If you chose (b), then here's my question for you: what if the omniscient Being knew for certain that the baby would suffer a fate worse than death, if it were not killed immediately? Would it be morally permissible for the Being to kill the baby as an act of rescue?

If you find it hard to picture such a fate, I'd like you to imagine a baby growing up in a truly hellish society in which child abuse is rampant, and in which every child gets abused repeatedly during its early years - and then goes on to perpetrate the same abuse on other children, as an adult. In such a society, it would be arguable that it would be better for a newborn baby if it were to die at birth than to go on living and become an amoral monster. Of course, we could never know that for sure in a given individual's case - but an omniscient Being could. In such a horrid scenario, God's killing the baby could be considered an act of mercy, to save it from an even worse fate than death. Thus the Golden Rule is not violated, after all.

My scenario may not be as hypothetical as you imagine, Professor Dawkins. Assistant Professor Clay Jones graphically details the wicked behavior of the Canaanites in his essay, We Don't Hate Sin So We Don't Understand What Happened To The Canaanites: An Addendum To "Divine Genocide" Arguments. I would invite readers to peruse this article: the depravity of Canaanite culture will sicken you. Child sacrifice, infanticide, bestiality, incest, temple prostitution: you'll find it all there.

Now I know you'll object: "Couldn't an omnipotent Being simply remove the danger to the newborn baby and thereby spare its life?" That's a fair point. But what if even after the danger was removed, the omnipotent Being had to perform an extended series of miracles over many years, in order to keep the baby alive? For instance, if the omnipotent Being were to kill all the adults in a society in which child abuse was universally practiced, then who would look after the babies? Who would give them milk? Who would teach them to walk and talk, and fend for themselves? The omnipotent Being would have to rain down manna (and milk) from Heaven, and teach them the requisite life skills Himself - a truly extraordinary series of miracles. Wouldn't it be simpler for the omnipotent Being to take each baby's life instantly? Remember that we're assuming here that each baby is going to enjoy Heaven forever, after it dies.

If you chose (c), then I would invite you to contemplate the hideous scenario I described in case (b) and ask yourself: is rescuing a baby from a fate worse than death tantamount to treating that baby as a means to some higher end? I think not. The reason why we never allow such acts in real life is that we are not omniscient: we simply do not possess the knowledge required to determine that a given person would undergo a fate worse than death (i.e. turning into an amoral monster), were it to live.

If you chose (d), then here's my question: what if the omniscient Being were able to take the baby's life without it suffering any pain or dread whatsoever - say, by simply shutting down its nervous system and mercifully rendering it unconscious before killing it? Would the omniscient Being's action of killing the baby still be wrong, if it were performed in order to save the baby from a fate worse than death, as in the scenario described in case (b)?

If you chose (e), then here's my question for you. What if the people carrying out the omniscient Being's command to kill:

(i) had seen a large number of collective (as opposed to private) manifestations of the Being, whose cumulative effect was so powerful and convincing as to leave no reasonable doubt among the people in that community as to the Being's reality, power, knowledge and benevolence;

(ii) had also been told by the omniscient Being that the baby would not suffer any pain or dread whatsoever in the process of dying;

and (iii) additionally knew that the baby was being rescued from an even more terrible fate than death by being killed now?

Would the people's action of killing still be a (morally and/or epistemologically) vicious one, in these circumstances? I'm not sure that it would. It seems to me that you could make a fair case that it wasn't a wrongful act, if conditions (i), (ii) and (iii) could ever be met. That's an epistemological question, and I would certainly agree that it is difficult for us to even conceive of how a tribe of people who were executing the command of a Being telling them to slaughter children could at the same time know beyond reasonable doubt that the Being telling them to do that was an essentially loving Being. But as a philosopher, I can't see any decisive argument showing that such a bizarre scenario is impossible. Improbable? Yes. Impossible? No.

Thus regardless of which reason you chose (a), (b), (c), (d) or (e), it appears that it's always possible to conceive of some hypothetical scenario in which it might be morally justifiable for the omniscient Being to painlessly take the life of an innocent baby in order to rescue it from an even worse fate - or even for it to ask human beings to take that baby's life. What's more, it's by no means clear that the action of these people in taking the baby's life would be wrong, under the extreme scenario being contemplated.

But once you've conceded that point, Professor, then your objection to the Canaanite massacres is no longer a principled one, but a practical one. In which case, all you're saying is that you don't agree with Professor William Lane Craig's judgement calls, rather than that you don't agree with his ethics. What you're really saying, then, is that in a narrower set of circumstances, you might have been prepared to do what the Israelites did around 1,300 B.C. (assuming the Biblical accounts are historically acurate, and that the events they describe really took place). Your primary concern would then be that the babies who were slaughtered should have been rendered unconscious before they died, so that they experienced neither pain nor dread in their final moments.

The obvious retort which springs to mind here is that a Deity capable of rendering babies unconscious in their final moments would also be perfectly capable of killing them Himself. Why would such a Being need to involve people in performing the horrid act of slaughtering babies at the point of a sword? Frankly, I don't know. My guess is that if neighboring peoples were aware that these slaughters had actually been carried out by the Israelites and not just by their God, then they would be more inclined to leave the Israelites alone, and less inclined to tangle with them, militarily.

But in any case, the point I wanted to make is that as a philosopher, I can think of no epistemic or moral principle which provides a knock-down argument against taking the life of an innocent baby at the behest of a Deity, under all possible circumstances, if the baby is killed painlessly. Can you, Professor Dawkins?

Now you might say that Scripture gives us no reason whatsoever to believe that the Canaanite children died painlessly, in the manner I described in my hypothetical scenario. I'll have more to say about this objection below. I would also agree with you that putting a screaming baby to the sword would be an unconscionable act. The point I wanted to make here is simply that the act of killing a baby at God's command, per se, cannot be shown to be wrong under all possible circumstances.

|

Question 8. Professor Dawkins, do you consider the God of the Old Testament to be morally equivalent to Hitler, like the atheist blogger Eric MacDonald at Choice in Dying (God, Genocide and William Lane Craig, 30 April 2011) or Santi Tafarella at Prometheus Unbound (Genocide or Justice?: William Lane Craig, the Canaanites, the Holocaust, and Jihad, 2 June 2011)? Is that your opinion? I don't recall you saying that to Rabbi Boteach when you debated him in 1996, although you subsequently wrote in The God Delusion, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006, p. 247) that Joshua's destruction of Jericho was "morally indistinguishable from Hitler's invasion of Poland, or Saddam Hussein's massacres of the Kurds and the Marsh Arabs." Do you, then, think that "Yahweh = Hitler" is a fair equation?

|

I would like to add that although I am not a Jew, I have personally visited Auschwitz and Birkenau, Professor. I've seen the death camps created by the Nazis. And I'd just like to point out one thing. Hitler wanted to annihilate the Jews, simply because they were Jews. The God of the Old Testament called for the extermination of certain peoples, because of their barbarous practices. Had they not engaged in such practices, God would not have wanted to end their lives.

May I point out that the same Old Testament tells us that we are all created in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:26) and even says: "Have we not all one father? Hath not one God created us?" (Malachi 2:10). Concerning foreigners, the God of the Old Testament says:

Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people, but love your neighbor as yourself. I am the LORD. (Leviticus 19:18, NIV.)When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them. The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the LORD your God. (Leviticus 19:33-34, NIV.)

Professor Dawkins, I put it to you that comparing the God of the Old Testament to Hitler is morally odious. Do you agree with me on this point?

|

Question 9. Professor Dawkins, do you realize that Professor William Lane Craig's views on the slaughter of the Canaanites are entirely in keeping with 2,000 years of Christian tradition, and that they were shared by St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, John Calvin, the Bible commentator Matthew Henry, and John Wesley, as well as being shared by some modern Christian philosophers of eminent standing, such as Richard Swinburne, whom you have debated in the past?

|