Click here to see the archive of past COTMs

This month

we explore one of the more popular constellations (especially among astrologers!)

Note the official spelling- Scorpius, not Scorpio.

This constellation is one of the few that actually looks like what it represents.

Scorpius is easy to find in the sky, if you have a clear southern horizon.

Next to Sagittarius, Scorpius is the lowest in declination of the Zodiac

constellations. To find Scorpius, wait until it gets really dark

(at least 10 or 10:30 local time). Then go outside and look due south,

as shown on the map. On June evenings, Scorpius crosses the meridian between

11 and 12 midnight. The meridian is an imaginary line drawn from due south

all the way up to due north. On our map it would cut through the red roofed

house and go straight up. The meridian is the point in the sky where any

given object (star, planet, moon, sun) is at its highest. After an object

rises in the east, it crosses the meridian, then heads west and begins

to set. It's much easier to see the effect in constellations like Scorpius

that are low to the horizon. Unless you're at a very dark site, the stars

will not be as bright as on the map. To see all of Scorpius above the horizon

can be a challenge, but a rewarding one!

This month

we explore one of the more popular constellations (especially among astrologers!)

Note the official spelling- Scorpius, not Scorpio.

This constellation is one of the few that actually looks like what it represents.

Scorpius is easy to find in the sky, if you have a clear southern horizon.

Next to Sagittarius, Scorpius is the lowest in declination of the Zodiac

constellations. To find Scorpius, wait until it gets really dark

(at least 10 or 10:30 local time). Then go outside and look due south,

as shown on the map. On June evenings, Scorpius crosses the meridian between

11 and 12 midnight. The meridian is an imaginary line drawn from due south

all the way up to due north. On our map it would cut through the red roofed

house and go straight up. The meridian is the point in the sky where any

given object (star, planet, moon, sun) is at its highest. After an object

rises in the east, it crosses the meridian, then heads west and begins

to set. It's much easier to see the effect in constellations like Scorpius

that are low to the horizon. Unless you're at a very dark site, the stars

will not be as bright as on the map. To see all of Scorpius above the horizon

can be a challenge, but a rewarding one!

The constellation Scorpius has a rich history, dating all the way back to the ancient Chinese, who saw the pattern of stars as a dragon. Another culture in the South Pacific saw a fishhook. In western culture, Scorpius is the nemesis of Orion the Hunter. After Orion's boast that he could slay any beast, the Gods decided to teach him a lesson by stinging his foot with a scorpion. It turned out to be a very hard lesson, since the wound killed him! But the Gods, ever compassionate, immortalized both adversaries by casting them in the heavens. To prevent them from fighting, they were placed on opposite sides of the sky; therefore, the two constellations will never be visible at the same time. Before the constellation boundaries were revised by the ancient Romans, Scorpius included the two main stars of Libra, Zubenelgenbi and Zubenelschemali. As you might guess, these are Arabic names, meaning the Northern and Southern Claw, respectively. In the image which you clicked on to get here, the Scorpion is pictured pinching those two stars in an effort to reclaim them! (Credit for that image, as well as much of the information in this article, goes to Chet Raymo and his wonderful book 365 Starry Nights, a must have for every amateur astronomer.)

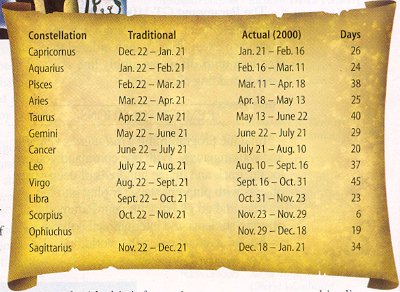

Another curious

fact about Scorpius, and the constellations in general, is that the traditional

dates that astrologers use to determine your "birth sign"- are wrong!

These dates were made up roughly 2000 years ago, and since then, the earth's

wobble around its axis has changed things. The dates have been pushed forward.

Also, the sun does not spend an equal amount of time in each constellation,

according to modern boundaries. In reality, the sun only spends 6 days

in Scorpius, from November 23rd to the 29th. The sun spends more time in

the "13th sign", Ophiuchius! Next time someone asks you your sign, try

telling them you're an Ophiuchius and watch their reaction! The table at

left shows the "traditional" zodiac dates and the "true" ones. (Credit

for this information and image: Sky and Telescope magazine, June 1998 issue.)

Another curious

fact about Scorpius, and the constellations in general, is that the traditional

dates that astrologers use to determine your "birth sign"- are wrong!

These dates were made up roughly 2000 years ago, and since then, the earth's

wobble around its axis has changed things. The dates have been pushed forward.

Also, the sun does not spend an equal amount of time in each constellation,

according to modern boundaries. In reality, the sun only spends 6 days

in Scorpius, from November 23rd to the 29th. The sun spends more time in

the "13th sign", Ophiuchius! Next time someone asks you your sign, try

telling them you're an Ophiuchius and watch their reaction! The table at

left shows the "traditional" zodiac dates and the "true" ones. (Credit

for this information and image: Sky and Telescope magazine, June 1998 issue.)

In this larger, more detailed view of Scorpius (adapted from Norton's Sky Atlas 2000.0), we'll take a closer look at some of the interesting sights in Scorpius. The symbols at left show how an object is best viewed:

![]() with your naked eye;

with your naked eye;

![]() with binoculars, and

with binoculars, and

![]() with a telescope.

with a telescope.

![]() Antares and M4. This is a good place to start when viewing Scorpius.

Antares, a red giant star roughly 500 light years from earth, shines through

the haze like the beating heart of the Scorpion. The name Antares means

"rival of Mars", and its easy to see why from its orange-red color. For

a dazzling photographic view of this region, click

here. M4 is a globular cluster, a close "neighbor" of Antares, visible with a 4 1/2 inch scope

from moderately dark skies. M4 is large but sparse for a gobular. The smaller globular cluster NGC 6144, nearer to Antares,

is a tough target, requiring at least a ten inch scope and very dark skies.

Antares and M4. This is a good place to start when viewing Scorpius.

Antares, a red giant star roughly 500 light years from earth, shines through

the haze like the beating heart of the Scorpion. The name Antares means

"rival of Mars", and its easy to see why from its orange-red color. For

a dazzling photographic view of this region, click

here. M4 is a globular cluster, a close "neighbor" of Antares, visible with a 4 1/2 inch scope

from moderately dark skies. M4 is large but sparse for a gobular. The smaller globular cluster NGC 6144, nearer to Antares,

is a tough target, requiring at least a ten inch scope and very dark skies.

![]() M80. Another

globular cluster, this one is smaller and arguably brighter in appearance

than M4, simply because it is more concentrated. A 4 1/2 inch scope will

show an indistinct, fuzzy blob, while a 6 or 8 inch will begin to bring

out individual stars at higher magnifications.

Picture and more info.

M80. Another

globular cluster, this one is smaller and arguably brighter in appearance

than M4, simply because it is more concentrated. A 4 1/2 inch scope will

show an indistinct, fuzzy blob, while a 6 or 8 inch will begin to bring

out individual stars at higher magnifications.

Picture and more info.

![]() Beta (b) and Nu (n)

Scorpii. To the eye, these stars both look like singular points of

light, but train a telescope on them, and you start seeing double. Even

smaller aperture scopes will split these doubles. Both are mismatched pairs,

consisting of one bright star and a fainter companion. The stars in Beta

are magnitudes 2.6 and 4.9, respectively, and are close together, only

13" (arcseconds) apart. The brighter star has a hint of yellow-green hue.

Nu, meanwhile, consists of 4.2 and 6.1 magnitude stars. These are a wider

pair, separated by 41". Not much color is discernable in this pair.

Beta (b) and Nu (n)

Scorpii. To the eye, these stars both look like singular points of

light, but train a telescope on them, and you start seeing double. Even

smaller aperture scopes will split these doubles. Both are mismatched pairs,

consisting of one bright star and a fainter companion. The stars in Beta

are magnitudes 2.6 and 4.9, respectively, and are close together, only

13" (arcseconds) apart. The brighter star has a hint of yellow-green hue.

Nu, meanwhile, consists of 4.2 and 6.1 magnitude stars. These are a wider

pair, separated by 41". Not much color is discernable in this pair.

![]() NGC 6302, The

Bug Nebula. Perched perilously close to "The Sting" in the tail of

Scorpius, the little Bug is in danger of tasting the Scorpion's venom.

See if you can track down this elusive planetary nebula. Use at least a

6 inch scope in very dark skies. It appears as a faint, rectangular smear.

With an 8 inch scope using medium to high power, some contrast is visible

toward the center, and the ends taper off in a U-shape.

Picture and more info.

NGC 6302, The

Bug Nebula. Perched perilously close to "The Sting" in the tail of

Scorpius, the little Bug is in danger of tasting the Scorpion's venom.

See if you can track down this elusive planetary nebula. Use at least a

6 inch scope in very dark skies. It appears as a faint, rectangular smear.

With an 8 inch scope using medium to high power, some contrast is visible

toward the center, and the ends taper off in a U-shape.

Picture and more info.

![]() NGC 6231. Next, we dip down into far southern Scorpius. This little

open cluster is a treat, if your horizon is clear enough to see it. Just

above a grouping of stars in the body of Scorpius, this cluster consists

of 5 or so bright, sparkling gems, orange-yellow in color. Because they

are so close to the horizon (as seen from mid-northern latitudes) the stars

twinkle madly, adding to the stunning effect.

NGC 6231. Next, we dip down into far southern Scorpius. This little

open cluster is a treat, if your horizon is clear enough to see it. Just

above a grouping of stars in the body of Scorpius, this cluster consists

of 5 or so bright, sparkling gems, orange-yellow in color. Because they

are so close to the horizon (as seen from mid-northern latitudes) the stars

twinkle madly, adding to the stunning effect.

![]() M6 and M7. Finally, we come to this pair of bright open clusters,

which are detectable to sharp eyed observers without any optical aid, from

very dark sites with no light pollution. They can be glimpsed in our Sagittarius

Milky Way photo, towards the bottom right of the image. Look for the

"Sting" in Scorpius to get your bearings. Both these objects are loose

clusters consisting of bright, scattered stars. M7 is the larger and brighter

of the 2. While you're focused on M7, try to spot the small globular cluster

NGC 6453, located just northeast of it. With an 8 inch scope and

medium power you should snag it!

M6 and M7. Finally, we come to this pair of bright open clusters,

which are detectable to sharp eyed observers without any optical aid, from

very dark sites with no light pollution. They can be glimpsed in our Sagittarius

Milky Way photo, towards the bottom right of the image. Look for the

"Sting" in Scorpius to get your bearings. Both these objects are loose

clusters consisting of bright, scattered stars. M7 is the larger and brighter

of the 2. While you're focused on M7, try to spot the small globular cluster

NGC 6453, located just northeast of it. With an 8 inch scope and

medium power you should snag it!