NINETEENTH ANNUAL REPORT 2000 & 2001

INTRODUCTION

BANASKANTHA

DANTA

SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOOD OPTIONS

WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: ADDRESSING GENDER CONCERNS

BAL VIKAS KENDRAS

DHANDHUKA TALUKA

EARTHQUAKE RELIEF AND REHABILITATION IN KACHCHH

RESOURCE & SUPPORT TEAM

POST-GRADUATE PROGRAMMES

MEDIUM-SCALE FININCE INSTITUTIONS OF WOMEN – A MEDIUM

OF EMPOWERMENT : A Concept Note

COMMUNITY-BASED ORGANISATIONS OF DALITS AND THE NEW

PANCHAYATI RAJ INITIATIVE: TOWARDS PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY : A Concept

Note

LIST OF BSC STAFF MEMBERS

INTRODUCTION1

It does not need iteration that India is today witnessing very turbulent times – social upheavals, political uncertainties, religious fundamentalism, increasing intolerance, uniform homogeneity being imposed on an essentially syncretic and plural social fabric. The vision of a new and resurgent India that Nehru outlined in his famous Independence Day speech lies shattered and betrayed. The enormous strides made, no doubt, in a few spheres of national life have apparently led to complacency, self-interest and neglect of certain sections of society. The story of India’s development is a story of two distinct Indias – one of bottled water and rising food stocks, the other of submerged lands and starvation deaths, with an unbridgeable gulf separating the two.

The Context in Gujarat

The present situation in Gujarat is a collage of contradictions - class disparities, inherent casteism, apparent non-violence hiding an oppressive social order, under-development of large sections hidden by the economic development of a few. Gujarat is a model state in more ways than one. It embodies all the contradictions of Indian society mentioned above and yet manages to remain in the frontline of the economically better-off states. The most compelling image of Gujarat is that of wealth, business, and enterprise. Together with this is the myth of a non-violent and peace loving, harmonious community. Gujarat is a classic case of how growth in certain sectors of the economy has been equated with overall development of the state and its people, an account which is not only misleading but evil in its intentions.

The image of Gujarat being highly developed is a partial truth being projected as the whole truth. In reality, the development of Gujarat has, over two decades, been equated with the tremendous strides it has made in industrial and infrastructural development. The mushrooming of small and medium scale industries along the “Golden Corridor” has been taken note of at international fora. This success gave further momentum to the establishment of a “Silver Corridor” and similar projects in other parts of the state.

The pattern of this development reveals disturbing trends. It is becoming increasingly clear that this development has been sans any long term planning as to its costs. The immediate visible impact has been the high level of land, water (surface and ground) and air pollution that these industries have caused (Hirway and Mahadevia, 1999: 82-92). There has been no ethical or social responsibility framework to guide this development (the High Court order asking the polluting chemical industries in Ahmedabad to clean up or close down is being made a mockery of). The occupational condition of the workers also has been known to be exploitative and hazardous. A study and visit by a Greenpeace (1996) delegation revealed the shocking details of the “Chemical Time Bomb” that the Golden Corridor has now turned into. The land is fast turning unfit for agriculture and cattle grazing due to slow poisoning; rivers with water polluted beyond recognition, with no forms of life left; borewells yielding coloured water which people are forced to drink; the poor being forced out of these regions due to destruction of their natural resources. All these are reduced into one economic category – “growth”.

The overall development paradigm followed by the government has over-emphasized industrial and infrastructure development to the detriment of crucial social sectors and ignoring the need for equitable regional development. Similarly, agricultural development has been extremely skewed, with prosperity seen mainly around the irrigated regions. The irony has been that the developed regions of Gujarat like Charotar (in Kheda and Anand Districts) and the irrigated regions of South Gujarat have been getting more and more water, while other regions like Saurashtra have been deprived of the benefits of development due to the absence of irrigation or any other measures for water conservation/watershed development. The solution that the political class has been advocating viz. “the lifeline of Gujarat” or the Narmada scheme, has itself exposed the paradigm of development that the State has adopted. Displacement of tribal and other communities, destruction of thousands of hectares of prime forest land, total lack of transparency as to the real social, environmental and human costs of the dam and numerous other problems have been thrown up by this model of development. The displaced population from other irrigation projects like Ukai dam in South Gujarat has now become permanent residents of slums in Surat city living in sub-human conditions.

The situation in Gujarat is, in many ways, a reflection of the national and international trends. The aspirations of the burgeoning middle class in India have not been fully answered by the new economic mantra, while the old caste and class based struggles have become sharper, brutal and more violent with each passing day. Polarisation on religious and communal lines has been used as a ploy to suppress the real social and economic contradictions in Indian society. A uniform religious identity is sought to be constructed and is being posed as the ‘national’ identity which works on the principle of exclusion; excluding an ‘anti-national’ minority which poses a constant threat to the integrity and security of the nation. It is the Brahminical order which seeks to propound an exclusivist pan-Hindu nationalist identity, directing all simmering discontent and frustrations at the ‘anti-national’ minorities and diverting attention from the centuries old caste and gender contradictions and preventing the assertion of any other identity which might disprove this ‘homogeneous, Pan-Hindu’ identity. Expectedly, we see strategies being used such as ‘cultural invasion’ leading to the decimation of ethnic identities and cultures, rewriting and misrepresentation of history and introduction of cultural and religious symbols as national symbols so as to shape the psyche of a whole generation. This strategy is also seen in the efforts of the Hindutva forces to appropriate the Ambedkarite discourse, in their effort to bring about a subtle shift by renaming the Adivasis as Vanvasis and in limiting the freedom of choice of women by excessively glorifying their traditional roles.

Moreover macro-economic processes of globalisation and liberalisation perpetuate the economic hegemony of the ‘First’ World over the ‘Third’ world. These processes operate mainly through ‘First’ world economic policies reinforcing unequal terms of trade, human and finance capital movements unfavourable to the ‘Third’ world nations, and creating institutions like WTO in which the domination of the ‘First’ world is complete. Where such economic processes do not work they operate through direct military and indirect intelligence operations whereby their economic and political interests are maintained. The managers of the nation represented by the politicians and the bureaucracy, mainly from the ‘upper’ classes and castes, respond to such policies in two ways:

Development and empowerment: evolution of the terms

The notion of ‘development’ has undergone vast changes over the past few decades, from a purely economic concept to one that encapsulates psycho-social, political and value dimensions. These include the following:

Economic factors: ownership, access and control over means of production and livelihood like land and natural resources; development of industries and other livelihood options which provide employment to a large number of people; creating a policy environment which would make credit available to the poor at easy interest rates;The shift from the growth model to the development paradigm itself had incorporated the aspect of distributive justice. In the words of Sen and Dreze “One way of seeing development is in terms of the expansion of the real freedoms that the citizens enjoy to pursue the objectives they have reason to value, and in this sense the expansion of human capability can be, broadly, seen as the central feature of the process of development” (1995: 10). Following the strides made by development economics it has been largely conceded that measurement of development must take into consideration factors other than economic alone. But even a cursory glance at the official reports and analysis in India will, even now, reveal the huge economic bias reflected in them2. We however recognise the fact that indicators other than economic alone have made inroads into development discourse and definitions.

Human factors: human dignity and respect; development of capabilities; existence of basic minimum amenities for human existence like nutritious food, good residential settlements, roads and means of transportation, means of communication, safe drinking water, facilities for health care etc.; educational facilities and opportunities to develop competencies for earning a livelihood; equitable opportunities ensured to girl children and women for the development of their capabilities; development of adequate social security and social defence mechanisms;

Political aspects: ability to participate in governance and politics in a decisive manner; special emphasis given to participation of women in the political process.

We believe that the development of any state should be measured from the condition of the most vulnerable communities/ sections of the population of that state. The indicators of development usually are averages that mask the pathetic conditions in which these communities live. In the context of Gujarat, it is essential to look at its much-acclaimed progress from the vantage point of the Dalits, tribals, the poorest among the OBCs, the minorities and women of these communities. It is our firm belief, guided by our experience, that the development that Gujarat has seen has eluded these groups. The following are statements of facts which we have observed in the course of our work:

In this light we examine the evolution in our thinking and understanding of development and empowerment – both concepts which are elusive and hard to define. Our understanding, as it has evolved, has been shaped and enriched by our work at the grassroots level and our own immediate experience of reality.

The concept of development, as it is commonly understood, indicates a movement towards a goal that is deemed as desirable from the vantage point of the communities in question or what is generally defined as desirable by the constitution and policies of the governments in power. In a way it is the end result that is indicated without reference to the necessary and sufficient conditions for realising this goal. Governments as well as development oriented NGOs lay stress on programme design, delivery mechanisms, policy framing and institutional arrangements as conditions necessary for the realization of this goal. However what we believe is that these are not sufficient conditions for attaining the goals of development, especially when we are dealing with situations where communities and individuals are controlled by ideologies of oppression and hegemony.

The various ideological dimensions that mediate the socio-political life of the communities and the country in general have been explained in the section on the context. The ultimate impact of these ideologies is to make the dalits, Adivasis and the minorities powerless, deprived of human rights, devoid of capabilities, assets and resources to survive. Empowerment, in this context, is the process through which communities and individuals counter these ideologies, appropriate personal, collective and institutional power and determine the course of their own development. This, in our estimation, is possible only through critical awareness and organised action. We are of the firm belief that development is ultimately possible for these communities only through this political process. (ibid).

Our contention is that it is possible to be empowered and still be at a lower stage as far as development is concerned, but it is difficult to be empowered only through (largely non-participatory) developmental programmes. The process of empowerment has to be essentially educational and organisational in its core. In the words of Ponna Wignaraja “… as the poor and vulnerable groups … deepen their understanding of their reality, they also, through greater consciousness raising and awareness, action and organisation, can bring about changes both in their lives and in society that will lead to human development and participatory democracy” (1993: 5).

Challenges before NGOs8

Gujarat has had a long and rich tradition of NGOs. Their contribution to the field of development is indeed immense. Yet it might not be out of place to suggest that the general approach has been non-confrontationist. It has resulted in NGOs working with the entire village, with all communities. This approach was based on an assumption that the village community was essentially homogeneous, and that this homogeneous community should be strengthened by building on common interests and values like harmony and peace. Such an approach would, deliberately or otherwise, overlook the inherent social and economic contradictions in the village. They end up, as they indeed have, implementing welfare programmes, sanitation and curative health schemes with the dalits and other ‘lower’ castes, but have side-stepped issues like untouchability and atrocities on Dalits. The Adivasis similarly were seen as communities to be uplifted and civilized disregarding their rich and ancient culture. They focussed instead on ‘educating’ and uplifting them and hence we see that one of the major interventions with tribal communities has remained running of ‘Ashram Shalas’ or residential schools were the tribal children could be educated but in an environment and language alien to them. This has tragically resulted in a generation of educated tribal youths severed from their cultural roots and their sense of identity shaken.

The point of the above critique is only to reiterate the fact that unless the NGO sector takes cognisance of caste discrimination and the deliberate marginalisation of the tribals as their take-off points for all interventions, they are sure to remain ambiguous in their commitment and hence ineffective in achieving the ultimate goal of social transformation.

We as an NGO address the following issues in the course of our work and we feel that it would help the cause tremendously if other NGOs took note of these issues.

The empowerment strategies in BSC have been enriched over time. From a Vankar community based approach9 where the counter ideology creation was limited to the assertion and confidence building of a single community (Heredero, 1979; 1989), we have moved towards a broad definition and recognition of a Dalit identity. This identity rejects the Brahminical order completely and challenges all Dalit communities to assume this political identity by shedding all symbols and practices of the Brahminical order. This identity is not a male identity but one that recognises the equality and paramount importance of the leadership of women in the political process. Also, our earlier approach focussed on organisational strengthening and all our efforts went into preparing the office bearers and the employees for sustainability of the organisation. This happened, unfortunately, at the cost of effective leadership from the community emerging10.

Our earlier empowerment strategy (approximately 1977-84) emphasised critical awareness raising in a Freirian sense using non-formal adult learning strategies. Critical reflection on experience and perception of reality in a community group was highly significant, thereby recognising the commonality of experience. This process was at the same time cathartic and establishing mutual support to culminate in a community action plan11, ultimately to result in an ability to bargain from a position of strength and dignity (ibid). The subsequent phase of developmental action (1985-97) was also equally strong on the empowerment dimension in terms of development of organisational capabilities in governance, management and institutional linkages. We have ample illustrations in the history of BSC that bears out this strategy; the village-wise awareness camps, the process of cooperative development, training in techno-managerial aspects of the cooperatives and the Federation, the search for new developmental projects like fisheries, sericulture, paddy processing, garments manufacture etc. The process of critical recognition of the impact of caste ideology and organised action were necessary pre-requisites for any developmental action, but once launched the developmental action itself was designed in an empowering way through its educational nature. Empowerment would be consolidated in the form of a strong people’s organisation.

More recently the empowerment strategy has been enriched by BSC’s recognition of the significance of the role of the state in development, the realisation and exercising of constitutional and democratic rights and people’s movements to achieve the same. The same applies to the attainment of entitlements in the form of basic human amenities, health, education, social security and welfare. The process of attaining these directly demands political participation in the various arms and agencies of the state in a collective and organised fashion. That in itself is an empowering process, and once attained, constitutes significant prerequisites for further development. This process is now familiar to us as seen in the various interventions taking place in Banaskantha through the Banaskantha Dalit Sangathan and the Adivasi Sarvangi Vikas Sangh (as illustrated in the sections on Banaskantha and Danta later in the report). It also educates us and the people regarding the way in which the political power structure replicates the discriminatory social system as revealed by the relatively low financial allocations for the oppressed communities and that too mainly in the welfare sector with only cosmetic allocations for asset building or access to means of production. This makes it obvious that these communities need a movement – struggle approach.

Our experience in Golana12 is today forming the basis of the struggle of the Dalit community against atrocities, for the right to life with dignity. It is becoming increasingly clear that constitutional and democratic rights and even franchise would have to be fought for, and calls for a movement approach. We are discovering through our experience in Banaskantha that struggle is a most potent way of empowering, as Ambedkar and many other leaders of political struggles have observed. The long-term process of struggle can be seen as progressional, interlinked and mutually reinforcing stages of empowerment and concomitant developmental gains.

There are many definitions of the term ‘social movement’ and a rather comprehensive definition is that of Paul Wilkinson “a social movement is a deliberate collective endeavour to promote change in any direction and by any means, not excluding violence, illegality, revolution or withdrawal into ‘utopian’ community” (Shah, 1990: 16). Of the various definitions of social movements available to us the one which perhaps best captures the essence of our understanding is the one by M. N. Zald and R. Ash: “a social movement is purposive and collective attempt of a number of people to change individuals or societal institutions and structures” (Desrochers et al, 1991: 3). To this we would add as per T. K. Oommen’s definition “…functioning within at least an elementary organisational framework” (ibid: 4). However as Ghanshyam Shah points out, the meaning and understanding of the term is essentially specific to the participants and their socio-cultural contexts (Shah, 2000: 16). Other interesting definitions of social movements are the ones by Ghanshyam Shah, M. S. A. Rao and H. Blumer (Desrochers et al, 1991: 3). A working definition, for the Centre, to emerge from the above discussion would encompass the definitions of Zald and Ash and T. K. Oommen and would thus be something as: “a social movement is a purposive and collective attempt by Dalits, Adivasis, OBCs, minorities and women of these groups, together or separately, to change social and political structures, functioning within an elementary organisational framework, to attain goals of social justice and human rights, and working within the framework of democratic mechanisms of the Indian Constitution13”.

The broad features of social movements to emerge from these definitions are: Sustained collective mobilisation as against individual/sporadic action; Stand for or against change; Presence of an ideology; More or less conflictual nature (ibid: 16-17). According to Shah the components of social movements are objectives, ideology, programmes, leadership, and organisation (2000:17). For us at the Centre social movements have most of the above components: mass mobilisation, a stand in favour of social change, strong presence of an ideology in the sense of working for and developing a counter-ideology to the dominant ones obtaining at present (caste, gender, communalism, ethnicity), providing a constructive opposition to re-shaping the state, formal and informal organisational framework whose ownership is with the people, and strong leadership from within the communities.

Further elucidating the point, Shah states the forms that social movements can and do take, what he calls ‘institutionalised action’ – “petitioning, voting in elections, fighting legal battles in courts of law, etc.” (ibid: 17); the other form, non-institutionalised collective action includes “protest, agitation, strike, satyagraha, hartal, gherao, riot, etc.” (ibid: 18).

The foregoing discussion makes it amply clear that the situation of Dalits, Adivasis, OBCs, minorities, and women is such that we can realise the impact at a district level to affect a larger number of people. In order for that to happen we have to broaden the scope of our intervention and hence a district level focus has been thought of14. As stated earlier, the Centre believes that effective social transformation and empowerment of the marginalised is well achieved through people’s power, where ownership and responsibility rests with the people. People’s organisations are an effective means of achieving this. Our experience in our earlier areas of engagement and the success of the people’s organisations there are proof of this belief. Further our experience also indicates that in the given situation individual efforts of Dalits Adivasis, OBCs, minorities, women have not borne much fruit; collective efforts on the other hand have resulted in an increased bargaining power of these communities vis a vis the elites and the powerful blocks.

It is thus clear that any activity henceforth, whether it is training or basic amenities or any other, will necessarily have to be tackled in the context of human rights of these communities or groups. This cannot be done in an individual capacity but will have to be taken up organisationally to be able to sustain the movement. For this we would be adopting a district level organisational thrust. All other aspects of our approach and strategy will be channelised through it. Having a district level emphasis would give us the advantage of:

The above-mentioned strategy of empowerment requires a sound understanding of democratic and constitutional rights and the legal provisions to deal with adverse response by the State or the oppressors. A large number of motivated volunteers with commitment, risk-taking abilities and competence to engage in constant learning and mass education would form the background of this empowerment process. The following steps are important in making it effective:

The following report is a consolidated report of the past two years – 2000 and 2001. Owing to the great tragedy following the earthquake of January 2000 and BSC’s intervention in the area of relief and rehabilitation it was difficult to bring out a report for that year and hence a consolidated report. The last two sections are concept notes on two of the emerging areas of BSC’s intervention – the struggle for women’s empowerment and participatory grassroots democracy.

[We are grateful to Tara Sinha and Ashim Roy for their comments and suggestions on this chapter.]

Bibliography

The Banaskantha programme is an embodiment of the new shift effected

by the Centre and the direction

adopted towards promotion of people’s movements of the marginalised

groups. The programme covers the 5 talukas of Banaskantha district – Palanpur,

Vadgam, Vav, Tharad and Dhanera. The work in these areas is heavily concentrated

with the Dalit communities. The present report outlines the activities

in this programme

in the calendar years 2000 and 2001.

It was in December 1999 that we at the Centre brought in a shift in emphasis from promotion of organisations of the marginalised to promotion of people’s movements of the marginalised groups against the denial of their human rights. This implied a shift also from a purely developmental approach to a more rights-based approach. The Banaskantha programme is a concrete manifestation of this shift. Our tentative steps in this direction now seem to be on firmer ground. Having achieved a measure of success in our endeavours we are hopeful of more positive outcomes in the future.

The mission and goals of the Centre in Banaskantha were outlined in the earlier report. To recapitulate the points briefly, we entered the area in the context of the Dalits of the area whose lives were marked by large-scale violations of their human rights in terms of denial of access and control over resources, the right to live a dignified life and the right to determine their destinies. Our mission in the area then was to work intensively with the people and accompany them in their struggle for justice and dignity. The concrete objectives, the strategy and the activities adopted towards this end are detailed in the sections below.

Background & objectives of the Programme

The objectives of the programme are:

As mentioned earlier there has been a shift in the approach that the Centre now takes in its work with the marginalised communities. With a shift in focus in the direction of broad-basing the intervention and taking it along on the path of a people’s movement there has been a consequent shift also in the strategy and mode of operation. We outline below the various activities undertaken during these two years. The discussion on activities will also highlight the key aspects of the strategy adopted to achieve this.

1.1 Mobilising and organising

As mentioned earlier the activity of mobilising and organising the

community was a crucial aspect of the strategy of the Centre. One of the

activities of the team was that of mobilising membership and support for

the cause of a Dalit organisation. The organisation was envisaged as the

Banaskantha Dalit Sangathan (BDS) and work of mobilising took place under

this banner, even before the actual registration could take place. They

organised various programmes such as rallies, sit-ins, conventions and

meetings (we detail below the actual programmes) with the aim of establishing

the identity of the organisation and making the organisational entity visible.

|

DALIT ASMITA RALLY Being in the area brought us into contact with the lived reality of the people of the area viz. employment, livelihoods, atrocities, basic amenities, and discrimination. The government officers got in touch with us. A one-day meeting was called jointly by several organisations of the area like the Banaskantha Dalit Sangathan, Banaskantha Viklang Trust, various unions of the SC/ST government employees. At this meeting various issues such as the reservation policy, roster promotion etc. The BDS made a forceful presentation of other issues plaguing the community, like atrocities on Dalits, livelihood issue, tribal rights and the issue of basic amenities. It was decided to hold a rally and present a memorandum to the Collector, and through the Collector to the President, the Prime Minister and the Chairman, National Human Rights Commission. Accordingly it was decided to hold the rally on 7th January 2000. Prior to holding the rally it was necessary to obtain the permission from the police which proved to be an extremely difficult task. It was granted practically at the last minute, late night on 6th January, and that too with severe conditions laid down for that. There was a big turnout at the rally, mostly comprising of Dalits from the rural areas. The urban Dalits and the government servants whose issue the rally was ostensibly about were few in number and were conspicuous by their absence. Looking at the composition of the rally the speakers gave voice to the burning issues plaguing the larger community in the rural areas. The rally was well covered in the local media. By any standards, the rally could be called a success. The very fact

that the BDS, as yet not a registered or legal entity, could mobilise people

in such large numbers speaks volumes for the work done on this front. It

also yielded us the advantage of wider publicity and awareness among the

public regarding the issues of the community. The message of the need for

a local organisation was driven home very forcefully without having to

say it. More importantly, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) took

note of it and started sending their replies to the BDS.

|

We had to encounter the reality of sub-castes within the Dalit group and therefore our endeavour remained that of fostering a functional unity within the various sub-groups in order to make the organisation truly representative of the Dalit communities and, more importantly, their issues.

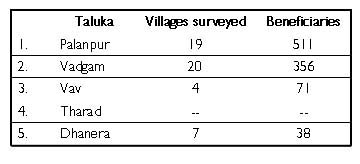

The organisational structure envisaged was outlined in the last Annual Report. The process of organising has gone more or less in the same direction. The major work entailed was in establishing the identity of the organisation at the taluka level. So far we have not registered the formal entity which is expected to be registered by February 2002 and which will be called the Banaskantha Dalit Sangathan (BDS). The membership position of the various taluka level units (as on 31st Dec. 2001) is as provided below:

|

MORIKHA CASE Village: Morikha Taluka:

Vav District: Banaskantha

Date of the incident: 19/03/2000

The issue involved a piece of land belonging to Ishabhai’s father, Chhatrabhai. Chhatrabhai owns a house adjacent to a plot of land that belongs to Khema Choudhary, an upper caste person, also the Sarpanch of the village. He had the intent of grabbing that piece of land. He had, on several occasions, made demands and pleas for that land but Chhatrabhai was not willing to give it up. On the day of the incident Chhatrabhai’s son was taken to Tharad on the guise of going on a picnic, by a friend of his called Isa Pira. He was murdered and his body was left hanging on the outskirts of the village. In order that the needle of suspicion not be pointed at him, Khema Choudhary himself went and informed Chhatrabhai that his son had committed suicide and that his body was hanging by a tree on the outskirts of the village, and even went and himself registered a case with the police. On the third day after the incident the members of the BDS went to the village and made inquiries about the event. Initially Chhatrabhai did not trust the emerging leadership of the BDS, and instead chose to go along with the traditional leaders who did not do much. So the case was not registered and no further action could be taken. Finally, after a year he decided to leave his village and camped, with his family and cattle, in the compound of the Collector’s office in Palanpur. After a year of thus camping there without any headway being made in the investigations he approached the BDS in Dec. 2000. Once the BDS decided to take up the case they used several tactics to publicise the event. Representations and presentations to the ministers and officials, memoranda and a postcard campaign were implemented. Press notes in various local vernacular newspapers were also issued. His demands were:

The Dalit Atychar Jyot Yatra - Dalit Atrocity rally also helped to draw attention to the case all over the district. Subsequently his daughter’s wedding had been arranged and he insisted on holding it in the compound of the Collectorate. This attracted media attention, locally and nationally. It was covered in the print media (dailies and in the weekly called ‘The Week’) and TV (Star News and Aaj Tak). The Dalits from several villages in Banaskantha converged at the Collectorate to show solidarity with Chhatrabhai in his quest for justice. In the meanwhile one member of the BSC Banaskantha team was selected

to represent the Dalit issues from BSC at the UN Conference Against Racism

(UNCAR) at Durban, South Africa. The local officialdom, fearing adverse

publicity, gave in to his demands. The government has accepted his demand

for a CID inquiry into the murder of his son. Additionally he has been

given 5 acres of land, and, a plot for housing in the village of Mandana.

|

|

RATILA: SO NEAR AND YET SO FAR Ratila, a village in Deodar taluka of Banaskantha district consists of 40 households of Dalits, apart from 400 households of Rajputs, some of Rabaris (OBCs) etc. The Dalits were agricultural labourers and in the year 1982 they registered an Agriculture Cooperative – “Shree Lavana Ratila Samudayik Kheti Sahakari Mandali Ltd.”. In 1984 the Cooperative made an application to the government for land for the cooperative. The District Land Revenue department surveyed the village and granted 150 acres of land to the cooperative. At this point of time this plot of land was free of any temporary or permanent structure. It was only after the land was awarded to the cooperative that the illegal occupation on this plot of land occurred, i.e. in 1984, when the Rajputs of the village built a temple to Goddess Ambaji on 2 acres of land. The Dalits did not oppose this. In 1997 the land was re-surveyed and this 2 acres’ plot was given to the village for performing religious functions. The rest of the land was divided among the 29 members of the cooperative. Some of the families started tilling the land. They put in great effort to improve the quality of the land after which they started sowing. The harassment started the year they started reaping the crops. In the initial years the harassment was not of a serious nature. However, this year the harassment has intensified; they have sown castor, Bajri, and pulses, and the agricultural output this year would have been approximately Rs. 5,00,000/-, had everything gone on smoothly. However the Rajputs destroyed the crop of each and every Dalit family. Two of the members raised their voice against this harassment and atrocity. They decided to file a case against the perpetrators of this crime. Hearing this the Rajputs thought of “finishing off” these two persons. When they got to hear of this plan the Dalits, a total of 61 members - 33 men, 16 women and 12 children, fled the village on 9th September leaving their property behind. Some of old people, the women stayed behind. The Rajputs had, since then, illegally occupied 15 acres of land. INTERVENTIONS BY THE PEOPLE

STRATEGY

1. Call a meeting of dalits of 84 villages of Deodar taluka

2. Meet the Collector and evict the illegal occupants of the land

3. To stage a rally in support of the cause of the 29 families

The rally passed off peacefully without any untoward incident. The Collector accepted all the demands, except the granting of cashdoles. The demands accepted were:

Thus it was that the people of Ratila, who had been camping outside the Collector’s office in Palanpur, decided to go back to Ratila in an State Reserve Police (SRP) van, along with 10-15 SRP personnel, on 24th of October. The plan was that the police and SRP personnel would help to remove the illegal structures on the land at Lavana and see to it that calm and peace was maintained throughout the operation. However, before this could happen, about 3000 Rajputs from surrounding villages assembled at Lavana, where the land is situated. A scuffle between the Rajputs and the Dalits followed. In order to disperse the mob the SRP personnel was about to fire at a Rajput but in the nick of time a Deputy Superintendent of Police pulled his hand back and the bullet was fired in the air. In the ensuing confusion one Dalit was injured seriously. He was immediately taken to the Deodar referral hospital which refused to admit him without a police complaint being lodged. He was then taken to the Palanpur Civil Hospital. A First Information Report (FIR) has been lodged at the Palanpur police station under the Prevention of Atrocities Act 1989 against 7 Rajputs. No arrest has so far been made since the procedure of the transfer of the police complaint to Deodar police station is underway. |

The other cases of atrocities which have come to our notice, and where action has been initiated by the Banaskantha Dalit Atyachar Sangharsh Samiti (BDASS), are listed below:

1.2 Creating a cadre of volunteers

We had sought to realise our goal of promoting a Dalit movement in

the region through the promotion of a cadre of volunteers who would represent

the issues of the people at the larger / higher level. This strategy is

based on the fact that we are going to be working at the area level in

5 talukas and this will necessitate the development of a volunteer cadre.

They could play an important role in the formation of the people’s organisation.

The volunteers would not have an organisational plan; rather their mandate would be to forever be vigilant and alert about the issues in the area. Therefore the question of professional accountability does not arise vis a vis them. This group of volunteers would be fluid i.e. it is not likely to remain the same; some may leave, others may join and more can be incorporated as they are identified. Strategically we could think in the lines of highlighting the village level issue of a particular village and get other villages to join the event.

The danger that needs to be guarded against is that of the volunteers starting to look towards the proposed organisation (BDS) as an outlet for power or employment. Therefore the challenge before us would be to sustain their motivation without unconsciously channelising their aspirations towards the organisation. Remaining in constant touch with them is critical to the success of this structure.

Selection criteria for volunteers:

We have met with limited success in this sphere of our activity. The reasons for this are discussed in the section below.

1.3 Women’s organisations

The organisations of women (the Savings and Credit Cooperative Societies)

were envisaged as the economic organisations of the movement and also a

concrete manifestation of the empowerment approach vis a vis women. In

this line the work progressed faster than expected. We had expected to

register around 2 cooperatives during the project period. However, on account

of the tremendous response of the women to the activity as also due to

the fact that our team members had built excellent rapport with the officials

in the concerned department we were able to complete the registration and

inauguration of all the 5 cooperatives in the project period. The position

of the various cooperatives as on 31st December 2001 is provided in the

sections on MSFI on page 44:

The output in this case has been sought to be achieved through a strategy of mass communication where the message of organising and coming together is communicated to a large mass of people. This is done through appropriate cultural forms which are more acceptable to the people. The message we seek to transmit is new i.e. of gender equality and ‘women’s rights as human rights’ but it employs media which are rooted in the culture and sensibilities of the people and the area. This serves the purpose of wider coverage and greater impact.

1.4 Awareness creation

Newsletters and Leaflets:

The BDS, with the aim of spreading awareness about the issues of the

area as also the message of organising, decided to start circulation of

a quarterly newsletter called “Banaskantha Dalit Sangathan Patrika”. A

function was organised to launch the newsletter on 25th February and it

was released by Mr. Hasmukh Parmar, Social Welfare Officer, Banaskantha

District. It seeks to disseminate information regarding the work of the

BDS, Dalit issues in the area, the movement for Dalit Human Rights, awareness

programmes and information on Panchayati Raj. A similar newsletter entitled

“Stree Awaaj” (Women’s Voice) is being brought out jointly by the 5 women’s

organisations of the area.

Apart from these newsletters, the BDS also brings out leaflets to disseminate information regarding some of the issues, the drought relief and the government’s response to it, or cases of atrocities in the area. E.g. they brought out two such leaflets: one was a public appeal to the people asking for support for Chhatrabhai and his struggle for justice; the other gave information regarding the measures initiated by the government to tackle the situation of drought and the various schemes of the government which could be beneficial to the people.

Dalit rights rally:

A Dalit Atyachar Jyot Yatra (Dalit Atrocity rally) was taken out by

the Dalit Atyachar Sangharsh Samiti from 9th to 18th June 2001, covering

88 villages of the 5 talukas with the aim of highlighting the issue of

atrocities on the Dalits. The rally would go from village to village and

would cover about 8 – 10 villages in a day. There would be cultural programmes

and other items which would talk about the particular issue of atrocities

on the Dalits. Since it came at a time when Chhatrabhai was camping in

the Collectorate at Palanpur, it also served an added purpose of highlighting

the particular case and the plight of the family. Two bye-products of this

rally were the increased awareness about the presence and work of the BDS,

and, a heightened sense of the essential oneness among the numerous Dalit

communities. This was a very visible expression of the strength of the

Dalit community and it seemed to convince the people that if they were

to seek redressal for atrocities committed against them then they would

not be alone in their fight for justice.

Apart from this the BDS also organised a huge rally on 22nd October in Palanpur to highlight the Rantila case and get justice to the affected families. The rally was organised following an uncooperative attitude of the local officials and bureaucrats to the case who challenged the Dalits to go to court. The rally was attended by both Dalits and Adivasis of Danta and was addressed by activists from the area as well as from Ahmedabad. It was only after the huge turnout at the rally that the Collectorate issued orders for the removal of encroachment under police protection.

Training programmes:

The trainings take the form of meetings where education is imparted

along with the implementation of the tasks. In the process of discussions

during these meetings the facilitators, usually from BSC, undertake the

clarification and explanation of the processes such as decision-making,

conflicts, development perspective, leadership and such like. Besides they

serve an important function i.e. of learning by doing where the team members

accompany the persons in their learning, providing timely feedback for

improved performance. They also serve the purpose of setting examples and

role models for the area and its people.

1.5 Drought relief programme

| The talukas of Vav, Tharad and Dhanera are the worst affected in terms of the drought. This has led to a severe scarcity of water, fodder and livelihood. The government survey showed faulty assessment and so the drought relief programmes were not started in time. Therefore the BDS decided to survey these villages. After the survey they held meetings with the village elders as well as with the taluka level committees of the BDS. They constituted ‘Drought Relief Committees’ in the talukas to make representations at the government level. They sent various memoranda to the Chief Minister, the Revenue Minister, the Taluka Mamlatdars and the District Collector. The state machinery did not take any action. This activity did not go further as there was a high level of frustration among the people; moreover it would have |

in village Baluntri of Banaskantha.  |

Year 2000

Year 2001

1.6 Earthquake relief programme

When the killer earthquake struck Gujarat on 26th January 2001 the

people of Banaskantha also decided to respond to this human tragedy. When

they learned that the Dalits were facing discrimination in the distribution

of relief materials they collected food items (flour, tea, sugar, bajri,

groundnut, grams, and water pouches) and mattresses. They went there themselves

and distributed the items to individual households. This gesture was all

the more commendable since the area had been under a spell of drought for

the last one year (then) and they themselves had been facing a food scarcity.

Vav taluka of the district was also affected to some extent by the earthquake. As part of disaster vulnerability reduction efforts in the area, the three villages of Baluntri, Daiyap and Mithavi Charan were selected for distribution of water tanks to 66 beneficiaries, through BDS in collaboration with Janpath Citizens’ Initiative. Besides this, the work of farm bunding was undertaken in Daiyap and Mithavi Charan and in Baluntri the work of pond deepening was undertaken. This provided much needed wages to the people affected by the drought as well as the earthquake.

* A Brass is equivalent (approx.) to 100 cu. ft. of

soil excavation.

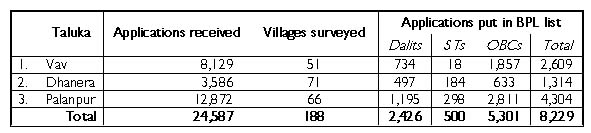

1.7 IRDP survey

In the 5 talukas of our operation we have noticed that in spite of

the fact that a large number of Dalit families are in fact living below

the poverty line their names have not been included in the government’s

“Below Poverty Line’ (BPL) list. Consequently they cannot receive the benefit

of various government schemes. The BDS took up the task of surveying such

families, making applications to the taluka officials for the same.

The economic benefit accruing to the families is shown in the table below:

1.8 Basic amenities

Drinking water

|

filling muddy water from virdas.  |

Village Madali:

The drinking water problem in the village of Madali was very acute indeed. Madali village is on the border of Gujarat and Rajasthan and neither state accepts it as part of its territory and the situation is very deplorable. With the drought conditions intensifying this year the drinking water problem of the entire village was an issue. BDS mobilised money from some individuals and provided water through tankers which saw them through the summer. Village Kundaliya:

|

2. Difficulties and limitations

At the end of the first year we can sum up the year and its achievements as:

3.1 Establishment of the identity of the local organisation

We have been successful in fostering a strong identity of the local

organisation of the area – the BDS, among the people as well as the government

and the bureaucracy. This is evidenced by the fact that people are coming

to the BDS from talukas which are not covered by us at present such as

Dantiwada, Amirgadh etc. The BDS has been able to press forcefully for

their entitlements and rights which were hitherto denied to them, e.g.

the basic amenities, the inclusion of families in the IRDP list. This in

itself is a highly political act because the allocation of funds for development

and its utilisation is fraught with local politics and dominated by the

vested interests of the area which the BDS has been able to challenge to

a certain extent.

3.2 Establishment of linkages with the government

Further, the image of the organisation is that of clean and honest

administration. Therefore the government also comes to BDS for implementation

of its schemes and surveys e.g. the IRDP survey or the fact that the govt.

(Dept. of Social Justice and Empowerment) requested the BDS to survey the

extent of electrification in Dalit households in the area. The relationship

with the government has been confrontational at times also, and the BDS

has taken strong stands for the people and against the anti-people and

high-handed attitude of the bureaucracy and local government officials.

It means that the BDS is taken as a threat by the vested interests operating

in the area.

*****************************************

footnotes:

BSC’s interventions in Danta taluka of Banaskantha district began in 1994. Since then the Centre has helped to set up a local organisation, Shree Danta taluka Adivasi Sarvangi Vikas Sangh (ASVS). Its current membership stands at 1634. The ASVS has emerged as a forceful voice of the Adivasis of the area, sourcing and managing many diverse developmental works for and on behalf of the community.

Introduction

Our effort during these two years has been to consolidate the achievements over the past five years in terms of establishing and developing the ASVS and the savings and credit cooperative of Adivasi women (the latter is reported separately under the section titled ‘Medium Scale Finance Institutions’ and will not appear under this section). The strategy adopted has been three-fold:

We were expecting to resume full-fledged implementation during the period October 2000 to March 2001 but the complete failure of monsoon even this year sent panic waves all over Gujarat. As far as Danta is concerned it was a serious spectre of famine that was emerging in the summer of 2001. So again, during the second half of the year, we were preparing ourselves to handle a much worse situation.

The following sections will outline the various activities undertaken in accordance with the programme objectives and the strategies as mentioned above.

1. Danta Taluka Adivasi Sarvangi Vikas Sangh (ASVS)

As a part of its strategy to make an impact on the livelihood issues of the people, the ASVS undertook the following activities this year:

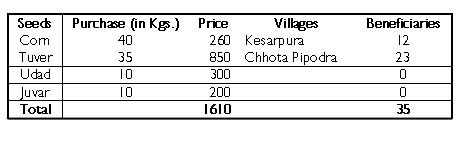

1.2 Seed and fertilizer credit

Due to failure of monsoon this facility was offered only on a modest

scale during the monsoon of 2000. The distribution was decentralized this

time to avoid inconvenience to the tribal farmers.

In October 2001 ASVS obtained a license, in the name of “Khanta ni Magri Irrigation Co-operative”, for the sale of fertilizer which would greatly affect the end-user, the tribal farmer, in terms of lower prices (a decrease of almost 5-8% as compared to the private retailers). Moreover, the ASVS can now earn a commission on the sale of fertilizer which would be an income for the organisation. This has broken the monopoly of the non-tribal agents (all such agents were non-tribals) who indulged in sale of fertilizer at exploitative rates. Besides this ASVS has also received permission for sale of seeds and fertilizers for agricultural use. This could translate into a possibility of setting up a seed shop.

Details of purchase and sale of fertilizer

Details of purchase and sales of local seeds

1.3 Capacity building and organisational development

of the representatives, committees and the employees:

An exposure trip, in collaboration with the agriculture department

of the state government, for 60 marginal farmers was organised to see the

white revolution belt of Kheda district to obtain a first hand understanding

of Dairying. In another exposure trip 11 ASVS members participated in a

Human Rights Rally organised by Legal Aid & Human Rights Centre (LAHRC),

Surat.

Several educational programmes were organised during the year with a view to enhancing the competencies of the various stakeholders of ASVS. The focus was mainly on strategic intervention in crucial issues affecting the region and the community. Besides effective programme implementation, emphasis was also placed on training for advocacy at the area level especially with regards to the severe drought situation and neglect of the development of the area and the community. The following table gives an account of the trainings organised during this period.

Year 2000

No. of participants in the various educational events:

ASVS representative training (Same group in all programmes):

On an average 50

ASVS Committee (Same group in all programmes):

On an average 12

ASVS employees (Same group in all programmes):

On an average 6

ASVS community leaders (from various villages):

On an average 55

Year 2001

No. of participants in the various educational events:

ASVS representative training (Same group in all programmes):

On an average 65

ASVS Committee (Same group in all programmes):

On an average 11

ASVS employees (Same group in all programmes):

On an average 7

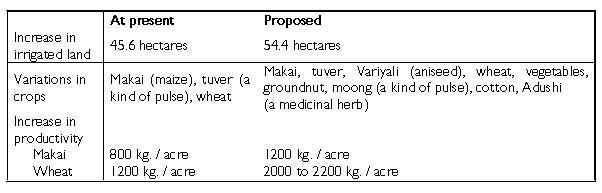

2. Watershed development programme

We believe that the key to sustainable livelihood in the region is watershed development leading to sustainable agriculture and allied activities. While the community in the area has been prepared through training and exposure trips to take on this approach, our present assumption is that the actual technical measures to be implemented can be financially supported only by the Government. This has prompted us to explore the possibility of obtaining funds for this programme from both the Central and State Governments. Project proposals have been sent to Council for People’s Action and Rural Technology (CAPART) which is the nodal agency of the Ministry of Rural Development (Government of India), District Rural Development Agency (DRDA, Banaskantha District, Government of Gujarat) and the Department for Co-operation (Government of Gujarat). All three proposals are pending approval.

2.1 CAPART:

In the early part of the year we submitted a proposal for watershed

development in 5 villages of the taluka covering 574 households over an

area of 1350 hectares. This proposal was rejected twice on flimsy grounds.

The first proposal was kept pending for six months and without any correspondence

whatsoever was rejected on the totally untenable grounds that the micro-watershed

proposed had more than 25% forestland. We submitted a revised proposal

in September ‘99 which was again not processed and rejected in March 2000,

taking advantage of a directive (passed in March 2000) of the Rural Development

ministry that all watershed programmes should be in regions declared by

the State Government as Drought-prone Areas. This ground also militates

against the basic principles of watershed development since the aim of

this approach is also to prevent any region from becoming drought prone.

We are beginning to suspect that there are ulterior motives behind such

delay in processing and subsequent rejection. We intend to take up the

matter at the highest levels. But at the same time we need to think of

an alternative strategy if the Government support would be further delayed.

2.2 District Rural Development Agency (DRDA):

We have applied to the D.R.D.A. (Banaskantha District) of the Gujarat

government seeking the status of a Project Implementing Agency (PIA) for

watershed development in the area. This proposal covers a total of 60 villages

situated in central, eastern and northern parts of the taluka. The application

for 1998-99 was rejected without showing any plausible reason. We have

submitted a fresh application. With the State Government we are less hopeful

because the application by BSC and by ASVS has already triggered off opposition

from the communal elements as well as the corrupt politician-bureaucrat

network.

2.3 Co-operation Department of the Government of Gujarat:

We had planned to initiate a Lift Irrigation project in Khanta ni Magari

village but the proposal is awaiting sanction. If this proposal is approved

it would cover a total land area of about 107 acres, 45 households, and

a Gross command area of 64.80 hectares. The project aims are:

However, we felt that despite non-cooperation from the Government we should go ahead with the programme with a fully community–sustained effort. Accordingly we appointed Abhigam Collective, an organisation with expertise in community based Natural Resource Management issues to assist the ASVS and BSC in this effort. We decided to initiate this on a small scale in three villages selected on the basis of certain parameters related to the stage of ecological degradation, watershed characteristics, agricultural productivity, water scarcity and community preparedness. Abhigam Collective has been able to study the situation in the selected villages intensively and has come up with a plan of action which involves various community based measures. Most of the measures will be executed by the people and some of the major ones will have to be financed by the Government or other agencies. Concrete steps were planned after the drought period and the monsoon of 2001. (A complete report of the study is entitled Towards Sustainable Livelihoods: Potentials for Rejuvenation in 3 Villages, Danta, Banaskantha by Vinay Mahajan & Charul Bharwada). Based on the detailed study, a proposal for community-based eco-regeneration in these three villages was submitted to Gujarat Ecology Commission. The project proposal is likely to be sanctioned by June 2001. The three villages selected for this intervention are Tarangada, Machkoda and Dhamanva.

Facilitation of effective implementation of Government welfare and development schemes

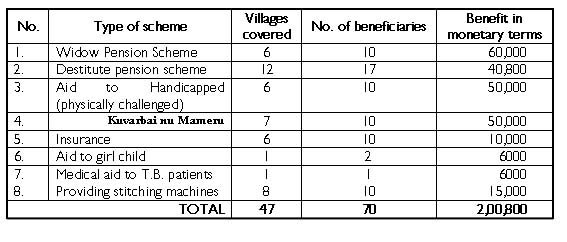

The following table gives the details of the various schemes of the government the ASVS managed to get sanctioned for its members.

3. Other Activities

3.1 Government Schemes – Implementation

Medical (T.B.) camp: Organised by ASVS and the Govt. Health department

No. of patients treated:

716

No. of patients diagnosed with T.B.

82

No. of patients who received free medicines

870

Total value of medication prescribed free of cost (for 6 months)

Rs.31,980/-

The TB diagnosis camp was organized at Hadad village on 11th February 2001 with the joint support of the government Health department. About 716 people came here for diagnoses out of which 417 were diagnosed as positive. The medical service was provided here by doctors of Prof. K. J. Mehta TB Association situated near Bhavnagar. The Commissioner of the labour department, Mr. A.M. Parmar remained present at the camp and the work was completed successfully under his supervision. A total of 870 persons were provided free medicines for TB continuously for 6 months by the labour department through the ASVS. There were two cases in the camp that needed a detailed check-up. They were sent to the Ahmedabad Civil Hospital by the Sangh and the check-up was done according to the instruction. Their cases were sent for financial aid to the labour department in order to cope with the extra expenses incurred.

Camp for the physically challenged:

The camp for the physically challenged persons was organised on 15th

July 2001 at Sandhosi village. The district health officer, Orthopaedic

Surgeon, Civil Surgeon as well as officers from other government departments

attended the camp. 116 beneficiaries from a total of 37 villages has come

to attend the camp out of which 110 physically challenged persons were

given certificates identifying them as being physically challenged. 84

out of them were given free bus passes by the social security office. Moreover

those who did not have crutches were supplied crutches too.

Thus, this activity carried out by the Sangh for the implementation of the government schemes has been a successful one. It gives benefits simultaneously to a whole group of people at one time and place.

Along with this we have divided the government schemes into two sections and its activities have been very effective. The details are as follows:

Drought relief work undertaken by ASVS and BSC with the assistance of Catholic Relief Services: (April-August 2000)

Conducting the survey has affected the identity of ASVS positively in the area. For one thing, this survey brought the ASVS in contact with non-adivasi villages and people who were also surveyed to be included in the BPL list. Therefore the earlier suspicion and mistrust of ASVS and its activities was replaced by respect and trust. Secondly, many government officials sent letters of acknowledgement for the good work done and promising support to the ASVS in its future endeavours.

SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOOD OPTIONS

Developing and initiating sustainable livelihood options for our

priority communities in our areas of intervention is an important activity

of the Centre. The task is to identify, initiate and stabilise agricultural

and non-agricultural income-generating alternatives and sustainable livelihood

options to increase the people’s skills and to decrease their dependency

on exploitative, seasonal agricultural labour. The aim is to link individuals

and communities with financial institutions, training institutions

and other resource personnel

to enable them to access the right tools and resources to succeed.

The following report details the activities undertaken in this regard in

2000 and 2001.

When we visualised working in the line of sustainable livelihood options

for the poor we had thought of actively pursuing livelihoods in the non-farm

sector, not ignoring the farm sector also. However this plan has not worked

out due to the economic environment hostile to the poor, lack of technical

and management expertise which is difficult for the poor to mobilise. Our

work in this line thus received a setback. The starting and winding up

of Jagruti Garments Ltd., a garment manufacturing unit set up in Petlad

is a case in point. We need to seriously rethink on this aspect of our

intervention. In order to augment the feasibility and sustainability of

their existing livelihoods (increasing productivity) options, goat rearing

and eco-regeneration at a micro level and organic farming have been thought

of.

| Last year’s report talked about the feasibility study undertaken with regard to promotion of goat-rearing in Danta as a secondary source of income-generation. Our endeavour was to introduce a scientific, commercial and entrepreneurial approach to this enterprise. Our plans for the same were also mentioned therein. However due to the drought which had gripped large parts of the state, and Danta was no exception, it was not possible for the activity to take off there. Yet, in Savli taluka of Vadodara district, where the situation of drought was not as severe as in Danta, it was possible to implement it on a pilot scale to derive learnings and experience of the activity. This is what we decided to implement in this |

|

The activity is not new for the Dalits and Adivasis of the area. But the problem lay in the fact that they carried it out on traditional lines: releasing the animals for grazing and getting them back at milking time. The activity was undertaken in 3 villages of Savli taluka – Maninagar, Karanchiya and Sankarpura.

Number of goats distributed in the 3 villages

1. Training of CEDC staff

It is essential that the staff of the organisation receive inputs related to the promotion of goat rearing as a sustainable livelihood option for them to be able to convince the people to move in that direction. Although the training of the staff in this regard has been on-going two training programmes for an intensive input were organised where the following points were covered:

In order to give the staff a practical exposure into the scientific goat-rearing methods exposure trips were organised.

2.1 Central Sheep & Wool Research Institute (CSWRI):

Situated about 110 kms. from Jaipur this institute, apart from the

infrastructural facilities, also has expertise with regards to the world

famous Sirohi breed of goats. This trip was organised in September 2000.

This institute also offered to sell male goats to us at reasonable rates

for the purposes of breeding.

2.2 Sirohi Goat Farm:

This is run by the Department of Animal Husbandry, Government of Rajasthan

in village Ramsar, Ajmer district and conducts research on the Sirohi breed

and its productivity.

2.3 Barmer and Shivganj tehsils of Rajasthan:

The shepherd communities in the villages here have been successfully

carrying out this business. To get a first-hand exposure to their methods

and success in goat-rearing visits to villages like Balera, Rafua, Janpatrasar,

Aati, Udarwa, Vadala etc. of both these districts were organised between

31st March and 2nd April 2000.

3. Networking

Networking was undertaken with Animal Husbandry department of Baroda district, the goat rearers of Rajasthan, Ramser Farm, Ajmer and the goat rearers of Banaskantha. In order to implement our plans of vaccination, castration and training programmes related to goat-rearing it was essential for us to secure the cooperation of these agencies for which networking had been initiated. The Director of the Animal Husbandry office in Fatehganj, Vadodara had directed the veterinary officer in Savli to extend all help to us in this matter.

4. Vaccination programme

|

The goat is a very resilient and strong animal and it has a capacity

to survive in varied environs and climatic conditions. But once it does

become sick it is difficult to bring it back to health. Therefore special

vaccines have been developed for goats. However, people in our sample villages

have been carrying out goat-rearing in a traditional fashion and were consequently

not very open to scientific methods such as vaccination and such like.

Our chief reasons for going in for vaccination were:

|

5. Monitoring system

In order for the CEDC staff to be able to undertake intensive monitoring of the entire activity, a special monitoring system had been devised and put into practice. The main objectives were to ensure that the goats were adequately taken care of and whether its growth was maintained, as well as to ensure that the sick animals were given timely medical treatment so that the mortality rate could be controlled. The monitoring system plays an important role in maintaining profitability. The aspects covered in the monitoring system were to do with rearing, health and shelter.

6. Medical follow up arrangements

We have been able to arrange for the free treatment and medicines for the sick animals. Almost 500 goats in the 3 villages were affected by the Foot & Mouth Disease (FMD) and they have received treatment. Apart from this there have been incidence of other diseases also such as goatpox, liver flu, and premature deliveries. We have been able to get the support of the Livestock Inspector, the Veterinary Officer and Deputy Director of the Animal Husbandry Department.

Details of mortality of the goats in the 3 villages

WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT:

ADDRESSING GENDER CONCERNS

Women’s empowerment has remained on the Centre’s agenda consistently

since the early 1980s.

The savings and credit activity was the concrete translation

of this concern into an achievable target; it offered immense scope for

immediate gains as well as a powerful symbolic tool of transformation in

gender relations. The MSFI function was earlier referred to as the Micro

Finance Institutions (MFI) and functioned within the overall thrust and

direction of the Centre for the particular area in which it was operational.

Its scope was thus restricted and circumscribed within a geographical boundary,

an activity which otherwise offered immense scope for mass mobilisation

of women for social empowerment. In the following report we describe the

efforts of the Centre to overcome this limitation and give the activity

a broad base and movement orientation.

Gender as a concern has manifested itself in the Centre’s programmatic approach and focus since the early 1980s. Debates and discussions as to the implications of such a stand, as well as locating appropriate strategies to operationalise this concern were undertaken. As a consequence of these several programmes and activities were initiated with and for women. The specific programmes for women’s empowerment such as the Community Health Programme (CHP), sericulture, adult literacy programme for women have been reported in the earlier annual reports. Learnings accruing to us from these undertakings coupled with intensive reflections with the women led us to the identification of the savings and credit activity as an appropriate intervention tool to address the gender issue.

The thinking behind this activity was clear: it was an economic activity by and for women. As an entry point for work in gender issues it was ideal as, at one stroke, it dealt a blow to the existing stereotype of women’s inability to manage large-scale financial activity in a professional manner. Besides, it was an activity which made a direct attack on one of the most fundamental aspects of gender imbalance viz. the economic dependence of women. We maintain that tackling social manifestations of gender inequality, important as they are, are frustrating if not accompanied by a creation of an economic base which offers some scope of bargaining and negotiating ones terms on a footing of equality. In sum, therefore, this activity is firmly rooted in our commitment for women’s empowerment, the activity of savings and credit being the strategy adopted to fructify this commitment.

Overview of the Medium Scale Finance Institutions (MSFI) activity

In keeping with the shift in approach, discussed in the introductory chapter, the Micro Finance activity was also taken up for in-depth discussion at the Centre. The discussion focused on the strengths and achievements as well as the shortcomings of the activity as it had been carried out till then. In light of that discussion a vision and strategy for the future were worked out.

Till December 1999 the Micro Finance activity was operational in 3 geographical areas of BSC’s intervention viz. Bhal of Cambay, Dhandhuka taluka of Ahmedabad district and, Danta taluka of Banaskantha district. The important achievements and successes of the activity to us seemed very much to be on the social parameters, although no effort till then had been made to chalk out specific criteria by which to gauge the progress of the activity. In the main they were:

* Non-productive assets include house, house repair and extension of the living quarters.

* Consumption expenditure includes expenses incurred on health, education, and consumption needs.

* Other expenses include expenses incurred on marriages, other social occasions.

1. Report of the activities during 2000 – ’01

1.1 Efforts at broad basing the activity

As discussed earlier the effort of the Centre was to make this activity

the main plank for a women’s movement, which would be a part of the larger

struggle for human rights of the Dalits, Adivasis and women. The challenge

was to transform a programme into a women’s movement for rights and empowerment.

This required a critical mass of membership as well as engagement with

the concerns of the membership to establish the credibility of the issues,

the people involved and the movement. Therefore it was necessary to increase

the number of such organisations from the existing 3 (in Bhal, Dhandhuka

and Danta).

We wanted to register at least 2 more such organisations in 2 of the

5 talukas of our intervention in Banaskantha. However, on account

of the tremendous response of the women to the activity as also due to

the fact that our team members had built excellent rapport with the officials

in the concerned department we were able to complete the registration and

inauguration of all the 5 cooperatives by June 2001.

| General assemblies of the new cooperatives:

The year 2001 witnessed 5 huge gatherings of women in Banaskantha district. The General Assemblies of the new cooperatives in Banaskantha were historic events in the life of Dalit women. No such event had ever evoked such an impact in the lives of women. The General Assembly created a sense of belongingness with the organisation. Each taluka level event brought women from approximately 35-40 villages together. Each event saw attendance of more than 400 women. Women came in tractors and jeeps to attend the General Assembly. For the first time women were getting up before a crowd of 350-400 to address the gathering, communicate the vision of the cooperative to women, and anchoring the show in front of Government officials and men of the community. |

Savings coooperative.  |

These structures helped to create the visibility of dalit women:

Dalit women are an invisible segment of society. Their contribution

was never recognised and their potential never given an opportunity. The

credit co-operative society provided such an opportunity. It is this structure,

which gave women an identity as office bearers/members of managing committee/President/members

of a modern formal organization. This identity made women visible. For

e.g. People now have started saying “Hansaben, president of Vadgam taluka

level cooperative spoke well”. Initially Hansaben was invisible but now

she has got new identity and her visibility has increased. So is the case

of many women who are the members of the cooperatives.

It further helps to break certain patriarchal beliefs and gender stereotypes and is therefore an invaluable educational tool. It is not claimed that all sorts of values and beliefs are broken but planned intervention to break such beliefs are already in process. The General Assembly of the Cooperative is one such intervention where conscious and planned intervention was done to break many beliefs about women. They were:

These structures helped women to create her assets i.e. financial

capital:

The savings from women’s point of view is security at times of vulnerability.

In Tharad taluka women have started depositing fixed deposits not with

the view of taking credit in future but to create an asset that would help

her in future.

The position of all the 8 cooperatives as on 31st December 2001 is provided in Table 1 and 1(a) below. As is evident from the table the position of the 3 cooperatives of Bhal, Dhandhuka and Danta is comparatively quite strong on account of the fact that they have been in operation for a longer duration. Not surprisingly therefore they have been giving out the credit facility for a longer duration and as of now a total amount of Rs. 60.42 lacs has been given to the members, the average amount of credit per member being Rs.3,531/- The rate of interest offered on savings also compares quite favourably with that of the nationalised banks, 0.5% more than the latter. The interest on credit is the same as that of the nationalised banks except in the case of Bhal where it is lower than the bank rates. This is on account of the larger volume of capital and savings at their disposal. 25% of the total members have availed of the credit facilities but the figure appears skewed because of the fact that the 5 recently registered cooperatives have not yet initiated the credit function.

Table 1 Primary statistics (as of 31st December 2001)

* Rates of interest of Nationalised Banks on

savings 4%; on credit 15%

** Average amount of loan per member Rs. 3,531/-

Table 1(a)

The perception of the cooperative in the minds of women, as also its

role and function, is well illustrated by the case below.

|

GIVE AND TAKE, JOYS AND SORROWS – TOWARDS SOLIDARITY A training programme for the Executive Committee of the Vadgam Credit Co-operative Society, the first of its kind for the participants, was held on 15th – 16th November dealing with the subject of evolving a vision and mission for the co-operative. Trainer: What is the objective of your Credit Co-operative Society?

Why do we need a women’s organisation?

There was a silence in the group.