The Codex Borgia

1. The Origin of the Codex Borgia

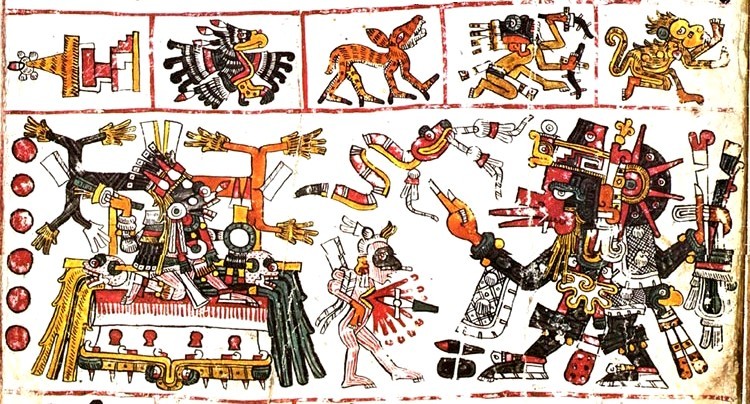

The Codex Borgia is one of the most beautiful of the few surviving

pre-Columbian painted manuscripts. The exact place of origin of this codex is

not known, however there is no doubt, that it originates from the central

Mexican highlands (possibly near Puebla or the Tehuacán Valley), an area which

was under Aztec rule at the time of the conquest. Obviously, this codex was

originally painted before the arrival of the Spanish, since it does not show any

European influence. It probably dates to the late 15th century. In the 16th

century it was sent from Mexico to Spain, and from there to Italy. The great

German scholar Alexander von Humboldt saw it in Rome in 1805 among the

possessions of Cardinal Stefano Borgia, who had died the previous year. Today

the Codex Borgia is housed in the Apostolic Library of the Vatican.

2. The Purpose of the Codex Borgia

The Codex Borgia is, like most

pre-columbian manuscripts, a religious book, made by highly specialized scribal

priests. They are not books in the traditional sense, of course, neither from

their way of production nor from their way of usage. There was not any type of

impression-making device, therefore no mass production was possible. Nor was

this intended, since those manuscripts are not made for just storing

information or reading stories for amusement. Stories were transmitted in an

oral tradition. The purpose of the mesoamerican books is rather to take hold of

time and the realm of history and religion. As it seems, images were more

important than words, especially with the Aztecs and other central mexican

peoples. Also, those books were not intended for reading them just individually

in a quiet chamber, but rather they were used in an active manner as part of

religious ceremonies when priests would make public readings, making

prophecies, or use them during consultations in order to give prognostications

of the lives of those who are about to marry or who inquire about the future of

their child, and so on.

3. The Production of the Codex Borgia

From the unfortunately very small sample size of mesoamerican

manuscripts, which religious zealousy and ignorance of 16th century Spanish

catholic culture has left posterity, we can suppose that each manuscript had

been handmade as a single, unique piece of art, although sequences of older

manuscripts had been copied frequently. Mesoamerican codices are screenfold

books: long strips of animal skin or amate paper, which are folded in an

accordion-like fashion. Afterwards the codices were covered with a white

lime-plaster coating, to enable the scribal priest to paint the manuscript,

using both mineral and organic pigments. All Mayan codices are made of

amate-paper which is obtained from the bark of the wild fig tree (ficus

cotinifolia). The Mayan codices read from left to right. The original of the

Codex Borgia is made of folded animal skin. The strips of skin were attached

end to end, folded into a screenfold, each page measuring 27 x 27 cm. This

codex is made of 39 leaves, with 37 of them painted on both sides. Two leaves

are painted on just one side, the back side being used to affix them to end

pieces, probably made of wood. This gives a total of 76 painted pages and a

length of more than 11 meters. The book is read from right to left.

4. The Content of the Codex Borgia

Of course, there is nobody alive anymore,

who could read and interpret this codex the way it was done by ancient Aztec

priests. So there is a lot of speculation as to the exact content of this

manuscript. However, we know for certain that it was a ritual book. The

original codex begins with a tonalpohualli,

which is a “book of the days“. It covers the famous ritual calendar period of

260 days, which is the result of the combination of 13 numbers with 20 days.

The next plates depict the 20 deities which represent those 20 days. There

follows a plate with the 9 deities of the night, next one finds an association

of the day signs with the cardinal directions. There are more pages about

astronomical planetary observations. Other pages refer to the solar year of 365

days, which in the Maya and Aztec calendar is made up of 18 cycles of 20 days

plus 5 extra days, called the unlucky days. The combination of the 365-day and

260 day-calendar results in the well-known calendar round of 52 years. There

are pages giving prognostications for each quarter (13 years) of this

52-year-period, when either abundance of food, or diseases and hunger, or

scarce or excessive rain are to be expected.

The longest sequence of the Codex Borgia

is also the most enigmatic one. It shows a narrative, or a story, and is

therefore unique. It is probably an account of historical events, probably

refering to Tula and Teotihuacan. Those are linked to many rituals like

sacrifices and ball games.

Finally, the codex contains plates which

were used as prognostication tools for the success of marriages. One of the

last pages shows a beautiful image of the sun god in company of 12 birds and a

butterfly, which together symbolize the 13 levels of heaven.

5.

The Description of the Aztec Gods and Day Signs

The reader will

next encounter a list of the 20 days signs and their corresponding Aztec gods.

1

alligator Tonacatecuhtli Supreme Male Deity

2

wind Quetzalcóatl Feathered Serpent, Wind

Deity

3

house Tepeyóllotl Heart of the Mountain

4

lizard Huehuecóyotl Old Coyote

5

serpent Chalchiuhtlicue Goddess of Running Water

6

death Tecciztécatl Goddess of the Moon

7

deer Tláloc Rain and Storm

8 rabbit Mayáhuel Goddess of Maguey

9

water Xiuhtecuhtli God of Fire

10 dog Mictlantecuhtli God of the Underworld

11 monkey Xochipilli Prince of Flowers

12 grass Patécatl God of Pulque

13 reed Tezcatlipoca-Ixquimilli Smoking Mirror with Bandaged Eyes

14 jaguar Tlazoltéotl Goddess of Filth and

the Earth

15 eagle Tlatlauhqui

Tezcatlipoca Red Smoking Mirror

16 vulture Itzpapálotl Obsidian Butterfly

17 movement Xólotl God of twins

18 flint Chalchiuh-

Totolin Turkey of the Precious

Stone

19 rain Tonatiuh Sun God

20 flower Xochiquétzal Flower-Quetzalfeather

→

back to main page Mesoamerican Codices