Iconography

Symbolism in Tibetan Iconography

All forms of communication and expression begin with simple signs and culminate as systems of symbols. These systems are utilized by the individual and by the culture that applies the symbolic system. Symbols originate from specific objects and the symbolic value of an object or image is derived from the meaning and emotions evoked. The mind of a person can create a unique symbol applicable to the individual life. Societies also create symbolic systems that are relative to and applicable to the collective. This is the kind of system that will be discussed here.

To understand the importance of religious art and iconography one must know the human mind. Faith and religion are vague concepts until they are given a face and a name. Human society operates in a world of symbols that the brain can create, adjust to and utilize. A single representation can invoke ardent awareness in a mind that a three-hour lecture will leave predominantly empty. External images are particularly important to a religious tradition with a theology as complex as Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhist Iconography consists of hundreds of separate deities and many of these deities have thousands of manifestations. They all have their origins in ancient Indian and Tibetan religious traditions. While the symbolic system often originated in the indigenous traditions of Hinduism and Bon, the actual symbolic images have evolved into a unique and intricate iconography.

Tibetan Buddhism has assembled an amazing inconographic system, the explanation in this document can only skim the surface. The main system is the organization of deities, which are primarily presented in thangka painting. Therefore, the focus in this text will be the typical symbolism of the main deities viewed in the Tibetan refugee community of Dharamsala. Each figure has basic parallel characteristics to inspect for interpretation.

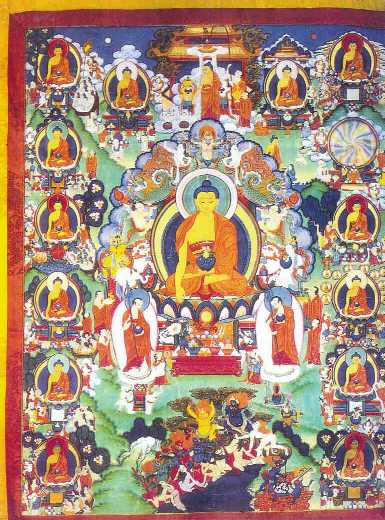

The typical set-up of a thangka consists of a large central deity, set in a landscape and surrounded by smaller complimentary deities. Every aspect of the painting has symbolic meaning but there are certain ubiquitous features that are necessary to examine in order to understand the entire image. The central deity is obviously of primary importance.

The physical traits of the primary deity should first be observed in order to identify it. One looks at the position, or asana (zug tang) of the figure, as well as the hand gesture called the mudra (chag gya). One will also notice the physical traits such as the skin color, the number of arms, the number of eyes, and the aura of the deity. A deity will commonly have subsidiary objects such as things held in the hands, a throne, clothing and ornaments. The other deities and the surrounding environment are also important aspects of thangka paintings. This is the typical structure of this form of religious art.

Another popular subject of thangka paintings is the mandala. Mandalas, first created in ancient India, play an integral role in Tibetan tantra. The topic of the symbolism of Tibetan mandalas could fill a hundred thousand pages and it is not possible to cover it in this document. However, as with the other topics, I will be able to skim the surface of the complex symbolism of a specific mandala.

The analysis of the symbolism applied in thangka paintings leads one halfway to a comprehension of the symbolic system. The other half of this system is the manner in which this system is viewed and retained by the culture as an entirety. Not every Tibetan is able to list the thousands of deities and manifestations of Tibetan iconography. However, there are certain images that all Tibetans are able to relate to and use as reminders and tools in the spiritual process.

Therefore, as a collective, Tibetans are a part of the symbolic system of Tibetan iconography, from the beggars on the street to the reputable scholars. The scholar, typically a monastic scholar, will have a more in depth understanding of the system. Tantra practitioners have the most contact with the symbols and are a necessary aspect of the continuation of the system.

In tantra, the practitioner not only views and reveres the different images but also seeks to identify with and symbolically become the images. The objective is to connect the symbolic image with the mental and physical existence of the individual, to make a psychic leap into the symbol and dissolve the self into it. In this way, the practitioners themselves can become symbols to the populace. Tibetans are aware of this practice and thereupon are encouraged to utilize the powerful images and carry on the symbolic system.

In the case of Tantric practitioners, the images and symbols are tools utilized to reach a certain goal. After this goal has been reached, mundane conceptuality ends and the images lose their significance. Like all objects and conceptions of samsara, religious images and symbols lack a true and absolute existence. Therefore, the system of symbols is created and utilized for the ultimate purpose of its own termination. In general, most Tibetans have not reached a state where this realization is possible but know it to be an immutable fact.

The religious art of Tibet has used the symbolic system in thangkas for hundreds of years and the basic symbols are common knowledge to the Tibetan populace. The iconography is understood on a fundamental level and is integrated into the religious perceptions of the cultural identity. This, in turn, shapes the collective identity throughout the generations, making the symbolic system an intrinsic part of each individual and the culture in entirety.

Shakyamuni Buddha (Shakya Thubpa)

The personage Shakyamuni Buddha is the historical founder of the Buddhist religion. He was born in southern Nepal of the Shakya clan roughly in the fifth century BCE. The term ‘Buddha’ means ‘enlightened one’ and is attributed to beings who have reached the highest level of enlightenment. When one discusses ‘the Buddha’ the implied topic is Shakyamuni Buddha. In this eon, the ‘Fortunate Eon’, there are to be one thousand Buddhas, of which Shakyamuni is usually considered to be the seventh.

By the time Buddhism reached Tibet, the actual history of the Buddha had become an expansive mythology that is often a subject for artists. There are many different depictions of the Buddha, such as Buddha involved in the twelve great acts or scenes from his former lives (Jataka), but the seated Buddha in meditation and earth witness gesture is by far the most popular in Tibet. The image on the previous page is a nineteenth century depiction of this topic.

This thangka portrays Buddha seated in the meditation pose with both feet exposed, dhyanasana (dorje kyil trung), and the two hands in bhumisparsa (sanon chag gya) mudra. Bhumisparsa means "earth witness" in Sanskrit and is regarding the experience of sitting under the pipal tree and being attacked by Mara, the demon of ignorance. Buddha touches the ground with his right fingertips, asking Earth to be his witness of good deeds.

All Buddhas have certain noticeable marks, thirty-two major and eighty minor, some of which can be seen in this thangka. This image of Buddha has a cranial bump (tsugtor), a mark between the eyebrows (dzogpu), and has large, pendulous earlobes. He is wearing monks’ robes and holding a mendicants begging bowl to display the vows of a monk.

This image also has two aureoles, auras around the body and the head. Aureoles show the divinity or saintliness of a being and also symbolize the radiating power of the voice and spirit of Buddhas. The fourteen smaller images of Buddha are similar to the central image, except one Buddha to the left is half hidden by a special radiating aura. This aura is coming from the Buddha’s center and is symbolic that a human is near. This displays that he is using his powers to reach this person.

Buddha is seated on a lotus throne, a common seat for enlightened beings. The lotus throne is a symbol of being born in purity and divinity. The backdrop of the throne is a cloud-like structure holding many animals. These are the six kinds of animals that represent the six transcendences of Buddhas; 1)the garuda for charity, 2) nagas for moral excellence, 3) dolphins for forbearance, 4) dwarves for endurance, 5) elephants for meditation, and 6) lions for the highest perfection of wisdom. Lions also are a trademark for the Shakya clan and are usually found around an image of Shakyamuni Buddha.

Before the Buddha, is an offering altar, the center piece being a wheel (chos kyi khorlo). This wheel is a frequently used symbol of the teachings of Buddha, the Buddhist dharma (chos). The wheel has eight spokes, representing the eight-fold path. Also on the altar, is a pink lotus, the supreme lotus and lotus of the historical Buddha.

Flanking the altar are two standing figures, Shariputra and Maudgalyayana. They were two of Buddha’s outstanding monks, they wear the monks robes and carry the mendicants staff (kharsil) and begging bowl. Buddha declared Shariputra held the greatest amount of wisdom and Maudgalyayana had impressive powers, such as shape-changing ability.

Above the figures, in the dark blue sky, are representations of the sun and the moon (nyida). These are extremely common in Tibetan thangkas as they symbolize the unity of the relative truth and the absolute truth, the final goal of meditation and spiritual training. They preside over the enlightened figures , displaying the power to unite beings in wisdom.

When a Tibetan Buddhist, either striving practitioner or common lay person, sees this thangka there are many things that come to mind. They may not know the specifics of every image but an overall feeling is acquired, a reminder of the faith and the origins of this faith. From the image of Buddha they can see an individual, a human being like themselves, who has reached a state of peace and joy. They see a human example as well as a great symbol of their Buddhist tradition.

Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig)

Avalokiteshvara, or Chenrezig, is a bodhisattva, and the cherished patron of Tibet. A bodhisattva (byang chub sempai) is an enlightened being that chooses to remain in cyclic existence to benefit all beings. The term bodhisattva denotes great compassion but Avalokiteshvara is the Bodhisattva of Inconceivable Compassion. Bodhisattvas have Buddha counter-parts and Avalokiteshvara’s Buddha is Amitabha. Amitabha emitted a white ray of light from his right eye, birthing Avalokiteshvara.

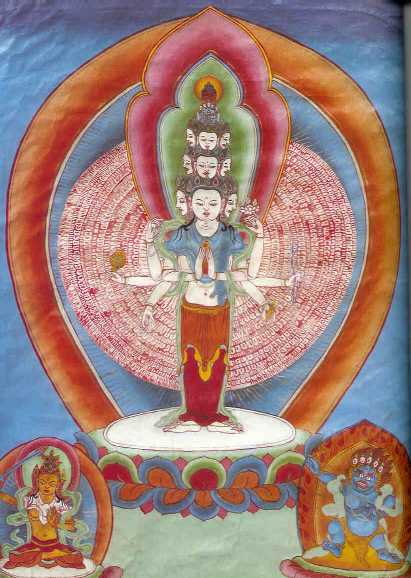

There are many different ways that Avalokiteshvara is portrayed, differing in amount of arms and focus of compassion. The image on the preceding page is the supreme manifestation of this bodhisattva, having eleven heads and one thousand arms. In Tibetan this representation is called, chak tong chen tong, meaning one thousand hands and one thousand eyes. Each palm has an eye to see humanity’s suffering and to illuminate all with the light of wisdom.

In this image there are eight main arms and 992 arms in a representational aureole that signifies the skillful means that Avalokiteshvara employs. Seven of the eight main hands are holding characteristic objects, the eighth hand in varada mudra (chog byin chag gya), the boon granting gesture. The front two hands are holding a wish-fulfilling jewel, prepared to aid the beings of cyclic existence. A full bloom white lotus (padma) is held, the white lotus being the lotus of bodhisattvas. Another hand holds a bow and arrow (zhuda), a three-fold symbol of the destruction of delusions, and the propagation of wisdom, and love. Below this is the hand holding a vase full of amrita (tshe), the elixir of immortality. The other two hands hold a wheel and a rosary that displays the prayers sent out to humanity.

Avalokiteshvara stands on a multi-colored lotus and has a triple aureole emitting from the eleven heads, denoting divinity and omniscience. There are two dharmapalas (chos kyong) protecting the good works of Avalokiteshvara.

Avalokiteshvara, in all of his forms, is one of the most worshipped deities in Tibet. Tibetans see Chenrezig as the bodhisattva with a special connection to the Tibetan people. He is thought to have fathered the race (see page four) and reincarnated as the first religious king of Tibet. Songtsen Gampo, the first Chogyel, is widely acknowledged as the original propagator of the religion in Tibet and is greatly revered. Therefore, he was the bodhisattva of compassion and his two Buddhist wives were manifestations of Tara (Dolma). After the Dalai Lamas gained power in the realms of religion and politics, they also were considered incarnations of the compassionate Avalokiteshvara. This major Mahayana deity is of particular importance for Tibetans.

Tara(Dolma)

In Tibetan iconography there are hundreds of manifestations of the female patron deity, Tara or Dolma. The two most popular are the White and Green Taras, Dolkar and Doljang. There are varying stories regarding the origins of the Taras, the most popular linking the feminine deities to Avalokiteshvara, therefore connecting them to the Tibetan people. The Bodhisattva of Compassion wept tears for the beings of samsara. From his right eye sprang a peaceful Dolkar and from the left eye a wrathful form of Doljang. The Twenty-one Taras (Dolma Nyichik ) are all seen as magnificently compassionate and eager to assist beings escape the suffering of cyclic existence.

An emphasis of the connection between Chenrezig and the Taras is the incarnation of both in Tibetan history. While the first religious king, Songtsen Gampo, is thought of as an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara, his wives were incarnations of the two popular Taras. The wife from Nepal, Tritsun, is considered an incarnation of Doljang and the Chinese wife, Wen-cheng is Dolkar. Both were major propagators of the Buddhist faith and were most likely much more devout than the famous king.

White Tara(Dolkar)

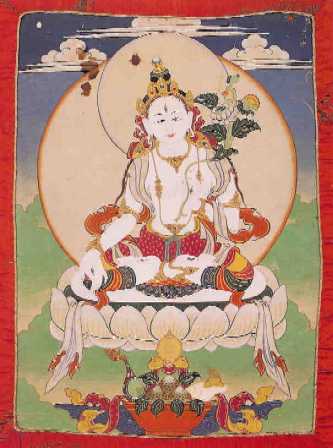

The first Tara image of the previous pages is Dolkar, the white manifestation of Tara. She sits in dhyanasana, the pose of meditation and holds her hands in vitarka mudra (chos jin chag gya). This gesture is a combination of abhaya mudra (jigmed chag gya) with a finger touching the thumb and varada mudra(chogjin chag gya), left and right hands respectively. Abhaya symbolizes protection and peace while varada denotes compassion and charity. Together, they symbolize discussion of the dharma and is sometimes called the mudra of explanation. It is commonly used by the great Buddhas and Taras.

White Tara is often represented with seven eyes, three on the head, on the soles of each foot, and the palms of the hands. Similar to the thousand eyes of Avalokiteshvara, this allows Tara to see the suffering of beings and to assist them. She wears beautiful gold jewelry and wears her hair in the jatamukuta style, the tiara like crown of hair of bodhisattvas. Both her aureoles are white and plain, symbolizing her purity.

Dolkar is seated on a white lotus throne and holds a white lotus in her hand, the lotus of bodhisattvas. Placed before her is an offering bowl with a lute, grain offering (tsamba), a wheel of dharma, and a conch shell holding the elixir of immortality. White Tara’s special function is to help beings elongate life, therefore she is considered the goddess of life. During the Teaching of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Tibetans made sure to not miss the White Tara Long Life Empowerment.

Green Tara(Doljang)

The second Tara thangka displays the green manifestation, Doljang. Like the White Tara her hands are in vitarka mudra, but she is seated in lalithasana (gyalpo zhug tang), the posture of relaxation. This is a common position for bodhisattvas. Her head emanates a rainbow aureole and she is framed in a gorgeous bejeweled background. She holds the blue night lotus, the utpala blossom, symbolizing the victory of wisdom over the senses. Doljang is invoked to assist in liberation, her golden green color pointing to her power in performing actions by extinguishing jealousy and war.

Both Taras are greatly loved by Tibetans. They are seen as infinitely kind and powerful. Their images are common for personal altars and are often chosen to make special prayer requests. Their beautiful and calm forms are the subject of love and respect as enlightened feminine beings.

Manjushri(Jampel yang)

Manjushri is known as the Bodhisattva of Wisdom and is the bodhisattva counterpart to Adi Buddha (Thogmai Sangye), the Primordial Buddha. He is the tutelary deity of astrology and generally the protector of students. Manjushri is often considered to be the Buddha’s incarnate wisdom.

The image of Manjushri on the previous page is a typical representation of this bodhisattva. He is red in color, illustrating his desire to be actively involved with aiding beings toward liberation, by way of wisdom. Manjushri is seated in dhyanasana and the left hand is in the vitarka mudra of bodhisattvas. He has a plain green head aureole and a body aureole surrounded by garlands. To complete the bodhisattva ensemble his hair is in the jatamukuta style.

In his right hand Manjushri holds the flaming double sword of analytic discrimination to annihilate ignorance, the fundamental cause of cyclic existence and suffering. The left hand holds a blue lotus (see page 42) surmounted by the book of transcendent wisdom, the prajnaparamita sutra. Manjushri is surrounded by over a hundred similar golden manifestations, symbolizing the universality of the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. In Tibetan history there have been two important scholarly figures thought to be incarnations of Manjushri, Atisha and Je Tsong Khapa. For information regarding Atisha see page nine. Je Tsong Khapa was a great scholar in the fourteenth century; reformer of monastic rules, author of several important commentaries, and founder of the Gelukpa sect. Both of these figures played a major role in the academic and religious environment of Tibet, so naturally they are connected to the Bodhisattva of Wisdom.

Palden Lhamo

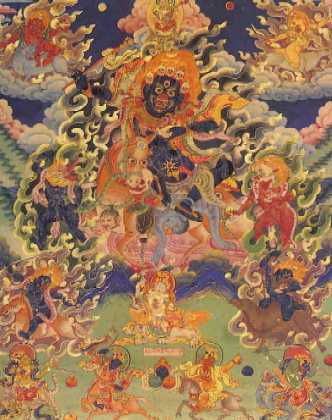

Palden Lhamo is one of the Eight Dharmapalas (chos kyong), wrathful protectors of the Buddhist dharma, and the only female Dharmapala. She is considered the wrathful form of Shri Devi, the wrathful Dharmapalas are usually considered to be Tantric deities. The symbols that surround Palden Lhamo, as well as her extensive retinue, are characteristic of Dharmapalas in general with a few additional symbols unique to her important role.

Palden Lhamo gained ascendancy in the Lamaist world as the personal protector of the Dalai Lama and the capital city and home of the Dalai Lamas, Lhasa. Therefore, the Gelukpa sect makes wide use of her image and she is the most frequently represented Dharmapala in Dharamsala. Palden Lhamo is pictured as a wild and energetic force that defeats the harmful force of egotism.

The image of Palden Lhamo on the previous page is a typical thangka of the fierce Dharmapala. She is riding a horse, an animal that can carry one across water, symbolizing Palden Lhamo’s ability to cross the ocean of cyclic existence. She has dark blue skin, a sign of her might in subjugating demons. Her three round, red eyes seek out the enemies of the dharma. She has long golden hair, sharp teeth to gnash vice, and has ash marks on her body from the time she spends in cemeteries. The aureole surrounding Palden Lhamo is fire-like, flames that consume passions and desires.

Palden Lhamo has many symbolic items surrounding her person. Her right hand wields the surmounted vajra (dorje) while in vajratarjani mudra (dorje khrobo digdzub chag gya). The vajra is an ancient weapon that in Tibet is thought to cleave in two the enemies of dharma. Vajratarjani mudra, a variation of tarjani mudra, is a gesture of powerful menace. Palden Lhamo’s left hand holds a skullcap full of blood and substances used in esoteric rituals, proving her tantric connections. Her garb is impressively grotesque; a diadem of five skulls, human skins, lion and snake earrings and fresh tiger skins.

There are certain items that make Palden Lhamo easily distinguishable from other Dharmapalas. In her hair she wears a moon, and near her navel a sun, symbols that are mirrored in the heavens above. Palden Lhamo’s main distinctive mark is the peacock plumage in her hair. The peacock is known to be able to consume a great deal of poison without coming to harm, therefore it symbolizes the eradication of sin, the ‘spiritual poisons’.

Palden Lhamo has an expansive retinue that is often pictured with her. Below her are five important goddesses, the Five Sisters of Long Life. They are ancient goddesses of Tibet, converted to Buddhism and integrated into Buddhist iconography. They are said to reside on Jomo gangkar, the glacier portion of the peak known to westerners as Mount Everest. The goddess above the other four is the leader of the Long Life Sisters and carries a vase with the Water of Life. Each sister has their own special vehicle and bears different items to assist beings attain long lives. The wish for long life is common in Tibetan Buddhism and it is an especially popular wish for the long life of His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Padmasambhava(Padma jungna)

Padmasambhava is one of the most revered historical figures in Tibet. A Mahasiddha (Dubthob) from India, he traveled to Tibet in the eighth century to conquer the indigenous demons and disseminate the dharma. (see page 8) There are eight main manifestations of Padmasambhava in Tibetan iconography. The most popular manifestation, and the name by which he is known by in Tibet, is Guru Rinpoche, the Precious Teacher.

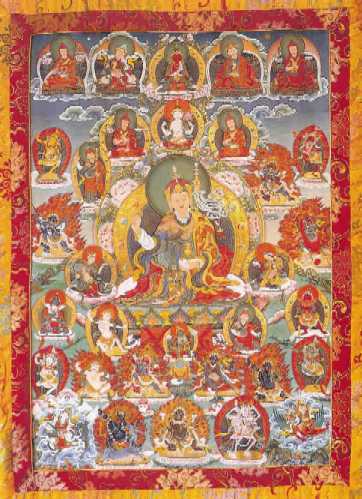

The thangka on the previous page is a typical image of Guru Rinpoche. He is seated in vajraparyankasana, the meditation posture with feet hidden to represent his esoteric nature. His body aureole is golden and bejeweled while the background has pink lotus, the supreme lotus of Shakyamuni Buddha. To those of the Nyingma sect, the "Sect of the Old" that Guru Rinpoche initiated, Padmasambhava is cherished like a second Buddha.

Guru Rinpoche is wearing lavish robes, representing the amount of honor he received in coming to Tibet. His characteristic head-dress has the ear-lappets turned up so that he can listen to all beings. Guru Rinpoche is holding a skull-cap filled with tantric liquids, a vajra, and a staff with a banner, human heads, and a trident (khatvanga). A banner is one of the eight auspicious symbols (krashi taggyad) and a trident (tsesum) symbolizes the Three Jewels (Konchog sum) and the tripitaka (denod sum). In his right hand Guru Rinpoche holds a vajra in vajratarjani mudra.

Guru Rinpoche is surrounded by various adepts and deities of the Nyingma order. Presiding over all, in the center of the highest plane of the painting, is Amitabha Buddha, whom Padmasambhava is considered to be an emanation. By his sides are Padmasambhava’s consorts, the Indian princess Mahadarava and the Tibetan dakini (khadama) Yeshe Khado.

Milarepa

The life story of Milarepa is one of the most recounted stories of Tibetan history and holy places related to him are scattered across the Tibetan landscape. His life is quite dramatic and connects with the common Tibetan in a special way, the topic being a person with a sinful past overcoming all obstacles and becoming highly realized. In the mid-eleventh century, Milarepa was born in the small Tibetan village of Kya Ngatsa to a wealthy family. At a young age Milarepa’s father died and the family was betrayed by the aunt and uncle.

From a young age Milarepa was an extraordinary being with a predisposition directing him toward the dharma. However, the ill treatment of himself, his mother and sister turned his path towards revenge. At the age of fifteen, when he was supposed to inherit his father’s fortune, Milarepa was sent out into the world to learn black magic. To save his family living in poverty and despair, Milarepa dedicated himself to the black arts. After going to two powerful lamas Milarepa caste a spell that killed thirty-five people in his uncle’s household. He continued to work evil spells and gain great amounts of negative karma.

Finally, Milarepa became disgusted and remorseful of his past actions and sought out a lama. He was lead to the great scholar and translator Marpa and became his disciple. Marpa understood Milarepa’s need to cleanse his sins before working towards enlightenment so directed him to extreme suffering. After many years of wretched ordeals and backbreaking labor Marpa began to teach him the dharma. The purified Milarepa became a extraordinary student, reaching liberation quickly.

After Marpa taught everything to the advanced student, Milarepa departed. He abandoned the worldly life and began a life of solitude and meditation. He traveled around the mountains of Tibet, singing enlightened songs to teach the common laity. He went to several mountain retreats, all of which are still famous today. By the time he died, Milarepa had many disciples and lay followers that sang his simple and direct songs of enlightenment.

The thangka on the previous page is a representation of Milarepa. He is pictured as a normal man, albeit with a pale and beautiful face. Milarepa is always shown wearing cotton meditation robes, as his name means cotton clad yogi. He is seated in lalithasana, the pose of relaxation and his hands are also relaxed. Milarepa’s head aureole is transparent, possibly denoting his appearance as a regular man. The cushion by his side displays his favorite activity in the latter part of his life, meditation. His throne is quite unusual for Tibetan iconography, a rocky precipice that represents his many remote meditation cave locations.

Under Milarepa is his spiritual master, Marpa. Marpa’s hands are in dharmachakra mudra (chos khor chag gya), representing his role as teacher of the dharma. Milarepa is surrounded by his four major disciples; Retchung Dorje Drakpa, Dampa Gyakpuhwa, Lukdzi Repa, and Gampopa Dao Shonnu.

The life and songs of Milarepa are some of the most read Tibetan works, both in Tibet and throughout the world. His exceptional life, the poignant songs he wrote, and the high degree of realization he attained are inspirational to all of humanity, particularly Tibetans. The message of Milarepa’s life story and great works have not faded with time and have remained as vibrant as the Buddhist religion itself.

Kalachakra(Dukyi Khorlo) & Vishvamata

Twelve months after his parinirvana (yongsu nya nganla dapa), Shakyamuni is thought to have manifested as Kalachakra in Sri Dhanyakataka, India to give the initiation of Kalachakra Tantra (Gyud). In English, Kalachakra translates as "wheel of time", a universal philosophy of Buddhism and a complex and esoteric concept of the Tantrayana (Dorje Thegpa).

Kalachakra resides in Shambala, a fascinating mythological city. It is thought to have been a kingdom of the distant past that disappeared into a celestial realm after the complete enlightenment of the society. It is believed that after a dark and barbaric period the kings of Shambala will return to save humanity. The dharma will spread and all of humanity will experience a great impetus toward enlightenment. There are parallels between this story and the prediction of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future who presently resides in Tushita heaven (Ganden).

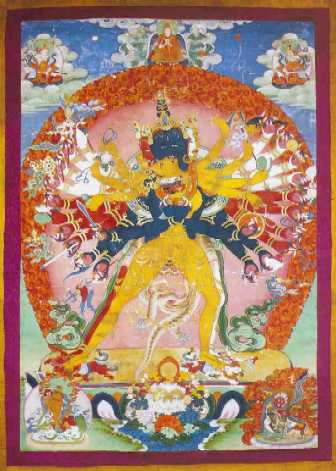

Kalachakra is usually represented at the center of the Kalachakra Mandala but it is a good idea to learn about this deity of the important mandala. Everything about the thangka of Kalachakra on the previous page certifies the tantric nature of this deity. The physical appearance of Kalachakra and the many objects manipulated are all steeped in tantric symbolism.

Kalachakra has four heads, twelve eyes, six shoulders and twenty-four arms. His heads and sets of arms are blue, red, white and gold. He is standing in yabyum with his consort Vishvamata, the Universal Mother. Yabyum is the symbolic union of method (male) and wisdom (female) which is the realization of emptiness. They are surrounded by an aureole of fire, flames that devour passions and desires, a common aspect of tantric representations.

Each of Kalachakra’s twenty-four hands and Vishavamata’s eight hands hold tantric implements or tantric weapons. Kalachakra’s front arms embrace Vishvamata and are crossed holding vajras. This is a variant of vitarka mudra employed by tantric deities in yabyum. The many weapons wielded symbolize the great power of the deities and their ability to fight against ignorance and demons.

The tantric implements include; vajras (dorje), staff (kharsil), ax (data), trident (tsesum), skullcaps (thodphor), conch shells (dungkhor yaskyil), rosary beads (thengba), wand (khatvanga) swords (raldi), chopper (digug), noose (zhagpa), chakras (chos kyi khorlo), skulldrum (damaru), and jewels (konchog). Many of these items are used in tantric rituals or symbolize mental exercises.

Kalachakra and Vishvamata are standing on the lotus throne, trodding on Ananga and Rati and Rudra and Guari. This displays the domination of the Buddhist dharma. Kalachakra is wearing a tiger-skin loincloth (tagsham), typical apparel for tantric deities symbolizing esoteric power. The offering in front of the couple holds pink lotus, a chakra, and a conch shell full of esoteric liquids (thun). Both the chakra and conch shell are symbolic of Buddhist law, or dharma.

Presiding over Kalachakra and his consort is Je Tsong Khapa. The influential figure Je Tsong Khapa became interested in Kalachakra and collected different teachings and empowerments to preserve the living tradition of Kalachakra Tantra. Therefore, Kalachakra tantra is of particular importance to the Gelukpa sect and the Kalachakra Mandala is frequently seen in Dharamsala as it is the seat of His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Kalachakra Mandala (Dukyi Khorlo)

Kalachakra was introduced to Tibet in 1027, along with the new system of calculating time. This also involved a change in the astrological cycle, shifting it to a sixty year cycle with the animals and five elements repeated twice. The making and utilization of mandalas is an ancient Indian tradition of Brahmins. It was integrated into the tantric ceremonies of Buddhism, specifically deity yoga (lhai naljor). They were originally used as a sort of communication with the celestial sphere.

The mandala is a representation of the entire universe, using deities and symbols of deities in certain orders. The microcosmic diagram, either two or three dimensional, is the only known way to begin to grasp the invisible forces of the universe. The dual nature of the material and non-material cosmos is displayed along with all the forces of time, evolution and involution.

A basic mandala is formed of circular or square enclosures around one central deity. Each area has several sets of different deities or symbols of deities and has four portals, on the cardinal points, each with protecting guards. In Tibet the south is to the left, the north to the right, east and zenith at the bottom and west and nadir at the top. While there are certain prescriptions for the set up of the different mandalas, this is known to be an open ritualistic art-form, in which there is an infinity of combinations between the deities and the enclosures.

The purpose of mandalas is mainly in the sphere of tantric practice, a subject of monastic meditations. However, mandalas are also the supreme symbolic system of Tibetan iconography and are useful for teaching. In the same way that thangkas of certain deities help humans relate to the traits of that deity, a mandala allows individuals to gain a conception of the impetus of forces in the universe and the deities through visual representations. This allows people to identify with these forces and find one’s own place in the cosmos.

The representation of the Kalachakra Mandala on the previous page is a sixteenth century thangka painting. This thangka has three main enclosures, five sections including the outer area. In the center is Kalachakra and his consort Vishvamata (see pages 54-55) surrounded by a circle of eight goddesses in the four cardinal directions and four intermediary points. The rest of the three main enclosures are square, radiating outward into the symbolic infinity. Each portal is depicted as a temple and is guarded by a deity in yabyum with consort and a retinue of supporting deities.

In the last main enclosure resides deities pertaining to time, suitable for Kalachakra which means wheel of time. The deities of the lunar months are all present along with Nagas (symbolic of seasons), cremation grounds, and Yoginis of Desire. All are important markers of the passing of time, allowing the individual to understand the endless cycle that all beings experience. Altogether there are seven hundred and twenty-two deities present in the Kalachakra Mandala, all with symbolic significance.

In the present day, the Kalachakra Mandala has undergone a rise in importance. In Dharamsala it is a commonly viewed symbol because of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Not only is it promulgated by His Holiness because of the position of the mandala in the Gelukpa sect but he has decided the mandala has special meaning for the modern world and particularly for Tibetans in exile. The mythology of Shambala (see page 54) is recognized as a call for the transformation of human society. Via the Buddhist religion philosophy, beings are able to evolve into a peaceful and unified society. Therefore, His Holiness believes the Kalachakra Mandala has relevance to humanity and he frequently performs Kalachakra initiations. This is particularly significant to lay people, as Kalachakra Tantra initiations are one of the few tantra initiations to be held publicly.

Dharmachakra, Chos Khor

This statue of the wheel

of dharma flanked by deer is found on the roof of all Tibetan

monasteries and temples. It commemorates the first turning of the

wheel of dharma in Deer Park in Sarnath, which is near modern day

Varanasi. After reaching enlightenment and being convinced to

teach the truths Shakyamuni Buddha had realized, he decided to

first teach his five ascetic companions who were residing in the

Deer Park. There he taught them and initiated them into the first

sangha. The teaching at the Deer Park in Sarnath began the

turning of the wheel that is now called Buddhism.