One's autumnal years bring with them change. Ambition vanishes, as do friends who pass away. On retirement, work, central to the earlier existence, is replaced by a void. One can experiment with activities as varied as woodworking, alcohol, bridge, or gardening. Not being mutually exclusive, these can be combined as in the often lethal trio of bridge, booze, and the Buick.

As I am transfomed into an octogenarian, I find myself staying off the highway and engaged once more in stamp collecting. It first fascinated me just after my seventh birthday when I received a small album, a packet of stamps, and hinges with which to adhere them. The folk wisdom about the aged reverting to childhood suddenly rings true as I lick stamp hinges.

After decades of neglect, my collection swells because of chance and circumstance. Recently, I acquired from a widow friend the collection of her late husband . My agreeable task is to bring order out of the chaos of thousands of unclassified specimens. I find myself wrestling with such arcane matters as the Cyrillic alphabet of Russia, Serbia, and Bulgaria or the size of the perforations at the edges of the stamps measured in number per each two centimeters.

All is not endeavor, however. I run into many childhood acquaintances among the miniature images: the domed Leopoldstat Basilia across the Danube viewed from Buda to Pest, Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary with his imposing mutton chops, a dark red Mexican airmail of 1934 with a snow-covered volcano flanked in the foreground by an organ cactus and the profile of an Aztec eagle-warrior.

As an adult I remain fascinated by stamps as official art: their content of nationalistic values and pride with a generous seasoning of propaganda. At age seven I thought of them differently. They became my window on the world. My first views of the Egyptian pyramids and the Athenian acropolis were through a magnifying glass. Kings, queens, emperors and empresses, peasants in regional dress peopled this world. Chinese junks, sweating steeds, tentative aircraft and puffing trains transported me vicariously around the globe.

Why wasn't I outside playing hide-and-seek or kick-the-can with other children? At this point in my life I was largely confined to my bed. Pneumonia had felled and almost finished me because it evolved into empyema, a severe infection of the plural cavity. The Fates inflicted upon me the double variety meaning that both lungs were affected. I learned years later that I was the tenth patient with this condition admitted to the Buxton Hospital for treatment, and the first to survive it. Antibiotics were yet to be discovered. My parents must have laid out my best suit.

This took place in Newport News, Virginia, to which we had arrived the year before from Roanoke, Virginia, where I was born 13 April 1928.

My mother, Mary Octavia Robinson, was from Standardsville, Virginia -- a village in the Blue Ridge Mountains thirty miles north of Charlottesville. She was born there in 1905 into a family, like most there, of English heritage. Her father, Charles Madison Robinson, was unlike most other men of the time, however, in marrying a divorcee, Mary Octavia Marshall. To some his behavior must have been thought scandalous, to others merely shocking. In order to accumulate a nest-egg, they migrated to West Virgina where Charles worked in the coal mines and Mary did heavy housework including meals and laundry for two boarders.

On their return to Standardsville they had acumulated enough money to buy farmland and build a house. By age ten my mother was orphaned along with her little sister Dora, their parents having died of some mysterious malady, or an undiagnosed disease. Their maternal aunt, Kate Marshall, and her husband, Charles J. Brooking, in nearby Somerset, Virginia, took them in and raised them.

My father, Reginald Julius Wicke, opened his eyes in 1901 at Whistler, Alabama, a small railroad center north of Mobile. His father, of second generation German lineage, worked in the shops there which repaired and maintained the rolling stock.

his brother Edward sits in the center, above him is my grandfather and on the

far left my grandmother Allie. Next to her is her sister and sister's husband.

Between the two children my great-grandmother Wicke.

My mother and father had met in Birmingham where Mary was doing her first two years of university study at Howard College (present-day Samford College). Reginald, who went by the name R.J. or simply "Wicke" because he abhorred the name inflicted upon him by his well-meaning parents, was working for the Alabama Light and Power Company. Having graduated with a degree in electrical engineering from the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, he was the first in his family to attend college. To help with his tuition, he joined the Students Army Training Corps along with Claude Pepper, who, later in life, became a US Senator from Florida. Fortunately for both, World War I ended before they were graduated . Mary found herself in Birmingham because an uncle, Walter Robinson, had moved there from Standardsville and become a food broker, offered her room, board and tuition expenses. She, too, was the first in her family to go to college.

Mary had completed two years of study, when R.J. decided to take a job in structural engineering at Virginia Bridge and Iron Company in Roanoke. They headed north together by train making sure they were not seen boarding it together, sitting in separate cars as the locomotive left the station. Not until 1976, on the occasion of my father's wake, did Mary tell me the story of their subterfuge. In vino veritas.

Mary finished her studies at the University of Virginia receiving a B.S. in Education in 1926. She had stayed with relatives in Charlottesville during the two years. The University constituted a male dominion at that time and granted the few females degrees in chemistry and education only. To be near Roanoke and R.J., she took a position at a public school in Bassett, Virginia, known, then as now, for furniture manufacturing.

R. J. and Mary were married in 1927 at the home of Mary's cousin Louise Van Leew in nearby Salem, Virginia. She arrived first and soon thereafter felt panic at the possibily that R. J. had suffered an automobile accident or some other ill fate. Someone prescribed a shot of bourbon to lessen her nervousness which she downed despite her religious affiliation which was Southen Baptist. Of course, R. J. showed up soon after and, therefore, I arrived ten months afterward. I am recorded as doing so in Vol. 1908, File No. 17087 of the state office for vital statistics in Richmond, ergo sum. Our residence at the time is listed as 604 Carolina Avenue, Roanoke.

A carefully kept Baby Book with a lock of blond hair and numerous photographs indicate that I was well received. It records my pointing at a buzzard circling the back yard while excitedly shouting the word "airplane." On being told that an automobile I was watching gleamed because it was new. I asked, "Did I shine when I was new?" My father referred to me as "the little sheik," after Rudolph Valentino the handsome motion picture idol whose tragic death in 1926 was remembered by all. Among the pictures in which he starred were "The Sheik" of 1921 and "The Son of the Sheik" of 1926.

In September of 1932 my mother returned to the hospital and came home after a few days with my new baby brother Ralph. During her pregnancy, she asked me to pray that God would send me a little sister with curly blonde hair like Shirley Temple, the child movie-star. After much discussion, he was named after the son of family friends: Ralph Long. An outstanding student at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, athletic, and handsome, Ralph Long's most attractive trait for my father was a commonplace name differentiating it from his own anomalous "Reginald."

Ralph arrived as the financial crises in the U.S. economy -- "The Great Depression" -- hit our family. Funds for construction of bridges and steel-framed structures were no longer abundant. The Virginia Bridge Co. cut back gradually to a four-day work week, then three, two, one, and none.

On the following Halloween evening three or four older boys knocked at our door shouting the traditional "trick or treat." Being without candy or other treats we failed to answer. There followed a loud thump on the porch. The "trick," a pumpkin, had spattered there on. By the following day Mary had produced a tasty treat: a pumpkin pie.

R.J. was reduced to drumming up odd jobs. He painted the exterior of someone's house. Fortune smiled at him when chosen for jury service. When the trial ended he brought home the green check he received in recompense. At dinner, he regaled us with details of the trial and the reasons he voted as he did.

Someone asked him to type a letter addressed to President Herbert Hoover proposing a scheme to end the Depression. It was several pages long and R.J. used his own typewriter. On presenting his modest bill, he was shocked when his client responded by saying, "This is a depression. I cannot pay. That was your patriotic duty."

R.J. later joined the C.C.C., the letters standing for Civilian Conservation Corps, a creation of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Congress passed the enabling legislation on April 5, 1933. One signed up for a period of six months to receive 30 dollars per month of which 25 went directly to his family. R.J. enlisted in the Forestry Service section and did surveying in the Great Smokey Mountain National Park near Bristol, Tennessee. C.C.C. organization followed that of the military as did living arrangement. Members slept in barracks or in tents. The food was good, but later in life R.J. would repeat the cook's motto: "There is no tough meat, only dull knives."

I was left at home with only Mother and little Ralph, who was stil nursing. Father was not too far away and would visit on an occasional weekend. At Christmas he brought home a tree and modest presents.

We had moved to a house at 217 Virginia Ave. For a boy the location could not have been improved on: a firehouse sat directly across the street. I soon got to know the fire-chief there, Captain Mills. Sometimes he would lift me up to the level of the fire engine siren from where I could grasp the crank handle and exert enough strength to produce the purr of a kitten. The even greater thrill was to go upstairs where the firemen slept and ride down the pole to ground level while held in the elbow of one of the men and land on the giant rubber dough-nut at the base.

My proudest moment among the firemen came to pass on June 15, 1934. On the previous day I had predicted the winner of the world heavyweight championship fight between Max Bear and Primo Carnera to take place that evening in Long Island City, New York. The fight between Max Bear, the relatively small American vs. the 280 pound Italian Carnera had generated great excitement. During my visit that day the firemen were laying bets with one another. One of them asked me, "Who's going to win Bear or Carnera." Because I knew what a bear was and had seen and heard a neighbor's canary I figured that a bear could defeat a bird. The fireman assuming that out of the mouths of babes came wisdom bet on Max. My prediction came true that night as Graham McNamee called the fight. In round eleven, after suffering ten knockdowns the "Giant with Feet of Clay" was counted out. My reward came the next day, in the form of a Dixie cup of vanilla ice cream which I savored with its flat wooden spatula.

We must have left Roanoke some weeks later given that in September I enrolled in the John W. Daniel school in Newport News, Virginia.

My father had obtained work at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company. The recently elected President Franklin Roosevelt had seen the need for a strengthening of naval forces in the Pacific and a new fighting ship was evolving: the aircraft carrier.

R. J. had proceeded us. Mary, baby Ralph, and preschooler Charles joined him via the Norfolk and Western rail line. R.J. had rented a unit in the Stratford Apartments: a four-floor walkup with a view of the James River and the shipyard. I was fascinated as the ships anchored offshore danced a precision ballet turning in perfect unison. This puzzled me greatly until I learned of tides.

The shipyard operated 24 hours a day. From our bedroom my brother Ralph and I could hear the constant ratatatat of the riveting as steel plates became part of the hull and its sound became our lullaby. Three of the carriers built by the shipyard -- "Hornet," ",Yorktown," and "Enterprise" -- were destined to play a crucial role in the "Battle of Midway Island" (4 - 7 June, 1942) that turned the tide against the Japanese in the Pacific.

at Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock

Company, 8 February 1937.

I was most fortunate in having as my first teacher a kind and sweet lady named Miss Jarman who would give us a hug once in a while. I liked my classmates, too. As it was a public school I came in contact with a social spectrum that included children who had no shoes as well as many classmates from the middle class.

On a Sunday morning of the following February I awoke to find myself unable to crawl out of bed and too weak to speak above a whisper. Our family physician, Dr. Walker, was called. After his cursory examination, I was rushed to the Buxton Hospital and immediately placed in an oxygen tent: a cube-shaped affair of green rubber and an isinglass window where one could peek in from the front. To the rear I could hear the clatter of a large container being filled with ice to lessened the odor of the oxygen.

My diagnosis was soon changed from the initial one of pleurisy to double empyema: an infection that filled both lung cavities with pus. Dr. Walker, thought the case was hopeless. Given Walker's insistence that nothing could or should be done, an intern, a Dr. White, who had been present at the examination felt compelled to break the rules by telephoning my father. White told him that surgery was the only hope of saving my life. R.J. called the owner, director and head surgeon of the hospital, Dr. Joseph Buxton, and asked him to take charge. My life I owe to the courage of intern White.

I was witness to the operation as my lungs were in no condition to handle ether. Only local anesthesia could be employed. As I was wheeled toward the operating room R. J. walked beside me and whispered, "You are going to be all right." I believed him even though he must have thought that this could be good-by forever.

My face was covered by a sheet under which the O.R. nurse peeked at me now and then with a concerned look. The pus in the left lung was so thick that it necessitated a piece of rib on my back be cut out.

After the surgery I required a blood transfusion. A coworker of my father with the required type offered to be the donor. We lay side by side on two gurneys as I received new life from him. Afterwards, he told me, "You have German blood from your dad and Scotch-Irish from your mom. And now you have some Irish blood, too."

I remained in the hospital for two months of treatment and recuperation. Two special nurses were hired to look after me working on twelve-hour shifts. Miss Farnham and Miss Ward had to turn me as I was too weak to move. They read to me Laura Lee Hope's "The Bobsey Twins at the Sea Shore," and others in the series as well as another featuring "Bunny Brown and His Sister Sue." Patricia Lauber's "Hans Brinker or the Silver Skates" I found difficult to identify with given his prowess in skating along the frozen canals of Holland. My two nurses seemed to me as angels. Young Dr. White, the intern, obviously shared my opinion of Miss Farnham as he soon married her. Misses Farnham and Ward left me with an admiration of their profession which I continue to hold.

My mother read to me, too. My father would visit after work bringing along my three year old brother. When little Ralph became bored and wished to go home he would pick up R. J.'s hat and jump up and down trying to give it to him. In retrospect, it seems unfair for the smallest child of the family not to receive the most parental attention. I'm afraid that my illness robbed Ralph of his entitlement.

My birthday was celebrated in my hospital room with a small cake holding seven candles, but I was not allowed to have a taste. Some days later, however, I became able enough to digest a small bowl of oatmeal: the most wonderful breakfast of my life. A second indication of my recovery was a trip to the sun room where one could look out on the glitter of Hampton Roads and meet fellow patients. The story of my survival had been passed along to them and being the smallest among them I was treated like a mascot. They even convinced me that my riddles were fresh and unknown to them. "Why does the chicken cross the road?" "For some fowl reason."

The upper storey carries a sun room facing Hampton Roads

When I left the hospital, spring had begun and the trees were green. I had just turned seven. A family friend took us home and my father carried me up the four flights to our apartment with ease. I weighed a mere thirty-five pounds.

Not wanting to fall behind my class I asked my mother to intervene with the principal to allow me to study and catch up. Since she had teaching experience he gave his approval. She taught me more than the required lessons. As she placed on my window sill two cigar boxes half filled with soil she said, "I want you to know how plants grow." With that she placed in my hand cotton and pansy seeds. I planted and watered them. Soon, tiny leaves greeted me one morning when I awakened. Bright many-colored flowers followed along with balls of cotton. I had observed a miracle.

A second activity during my recovery, philately, occupied me as well.

Gradually I put on weight, learned to walk again, and daily life returned to normal. It was thought at the time that sunbathing was theraputic. Therefore, we spent several hours out on our small balcony where I studied. I also thumbed through the pages of the latest "Silver Screen" magazine to which mother subscribed.

Dr. White, the courageous intern, and Nurse Farnham my mother invited to a celebratory dinner. Not only did we celebrate my recovery, but their engagement. While saving my life, they fell in love. As usual when guests were entertained Lynhaven Bay oysters were served which R. J. shucked and Mary fried. As was his custom R. J. decorated each oyster on his plate with a festive topping of bright red ketchup.

The following September, I reentered school. Rather than joining the friends I had made in first-grade, I was assigned to another section, that of problem students and slow learners. Apparently the principal had decided that given my long absence and home study I required special help.

My dedicated teacher, Miss Moore, who wore a brown dress that covered her ankles, seemed to me an ancient phantom from her mountain of gray-hair to her high button shoes. The Civil War remained close in her memory: obviously a Daughter of the Confederacy, she had achieved school-wide fame by refusing to let the name of Abraham Lincoln pass her lips when teaching American history -- no easy task, if true. She was especially nice to me, given my frailty and my motivation for learning as contrasted with most of her regular students.

Motivation paid off. The following semester I happily rejoined my friends from my original first grade class.

In the fourth grade I noticed some difficulty in reading the black board. To overcome this I discovered that I could bend light like a pin-hole camera. By joining my thumbs and forefingers to form a tiny ace of diamonds hole, I could peer through and obtain a clearer image. During the year an eye test was given to the class and I was unable to use my finger camera. I was pronounced near-sighted and sent to White's Optical shop whose motto was "You can't be optimistic with misty optics." After picking up my glasses I walked out into the street and looked at the rows of sycamore trees lining the street. Atop the trees I could discern individual leaves for the first time dancing in the slight breeze. Another miracle!

The transformation was not without a price, however. The lenses were of fragile, dangerous glass. Before I had them I could not see well enough to play baseball or sand-lot football. Now that my vision had improved I remained sidelined not only because of my frailty, but that of the glasses.

At this juncture I hit upon boxing, a sport in which one was face-to-face with an opponent, so close that lenses were not needed. A couple of older neighborhood boys who owned gloves and a much thumbed book on the sport were of great help. Through them I met a fellow who claimed to have had a short career as a professional pugilist. He taught me not to step backward, but to one side, to block a hook by raising the forearm to the level of the head. In difficult moments, one could spit in the face of the opponent to loosen his composure. When in danger of being knocked down one should fall backward on his own. This advice proved to be sound in practice.

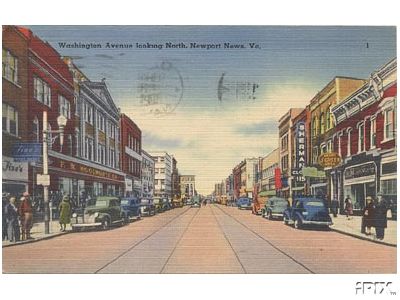

Although my glasses had curtailed my sports, they sharpened the motion pictures. On Saturday mornings one headed for the ¨"Street of Dreams." This was three blocks of Washington Avenue holding four movie houses. Plunking down a dime at the Warwick Theater allowed a frail child to enter a heroic world of daring deeds amid perfidy. The feature film was invariably a "cowboy or wild west show" starring Buck Jones, Hoot Gibson, Roy Rogers, Gene Autry or Johnny McBrown, whom R.J. had known at the University of Alabama. Accompanying this fare was the episode of a "serial," perhaps Buck Rogers in contest with the evil oriental-featured Ming - or Tarzan lording it over benighted Africans. But first came the Kiddie Club. At center stage a contemporary would belt out favorites of the moment: "On the Good Ship Lollipop", invariably sung by a Shirley Temple look-alike rubbing her midsection while phrasing ". . . or you'll get a tummy ache," or Red Sails in the Sunset, rendered perhaps by a lad who demonstrated difficulty in reaching the low notes.

The more sophisticated fare at the Paramount Theater attracted an older audience with a higher ratio of girls. Here one could see, for example, the "Road" pictures of Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour, as in "The Road to Zanzibar" (1941) and "The Road to Morocco" (1942).

The live entertainment before the picture was more sophisticated, too. As the lights went down, the faint notes could be heard as if in the distance. The music gradually increased. as the organ slowly rose from the pit, music matching movement. As if by magic, spotlights popped on, their beams lighting upon the slight musician and mistress of ceremony at the console. She accompanied the singer soloists on the sonorous pipe organ. Her name: Gladys Lyle.

Once a year the live magic show with Harry Blackstone, Sr., played at the Paramount. Each year I happily answered his challenge for a member of audience to come forward and witness his skills up close. My intention was to unmask Blackstone's secrets. How naive of me! He befuddled me making handkerchiefs and balls disapper in a way that was obvious to his audience, and made me look like an idiot. The organ background that Gladys rendered added so much to the show that one year Harry persuaded her to go with him on the road: a real road. And so she left us, and things were never the same.

At the other end of the strip the James Theater competed with the Warwick for the young viewer. Here was experienced The Popeye Club, with the theme song "I'm Popeye the Sailor Man" and a Max Fleisher Thimble Theater Popeye cartoon with its feature. Before the films it offered the usual singers interspersed with boxing matches between volunteer pugilists who, like the vocalists, received a free admission ticket for their performance.

The remaining cinema, the Palace, had no children's show, but depended on higher quality MGM movies to attract an older audiences. Shirley Temple, the most famous female in the world, starred there in pictures with the word "little" in their titles: In 1935, The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel; and in 1939, The Little Princess. Members of the NNHS Class of 1945 identified with the cute curly-head as being of the same age: someone they grew up with.

Indeed, as we left childhood we gave up the Warwick and the James for the Paramount and the Palace. Putting aside childish things, we began to wrestle with the mysteries of puberty. Glandular changes produced new and mysterious longings.

The silver screen came to the rescue with a timely series of motion pictures that dealt with our problems. Offering us didactic vicarious experiences at the Palace were the Andy Hardy films, considered by their producer, Louis B. Mayer, as his contribution to the strengthening of America's family values.

As adolescents we perceived the Hardy films differently from Mayer's intent. Girls on observing the female leads saw the growing power of their newfound nubility. Boys readily identified with Mickey Rooney's bumbling approach to dreamlike, chaste, co-stars such as Kathryn Grayson, Judy Garland, and Ann Rutherford in pictures with descriptive titles such as: Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever (1939); Andy Hardy Meets a Debutante (1940); and Andy Hardy's Private Secretary (1941). Lewis Stone played Judge Hardy, the sagacious father, whose "man-to-man" talks invariably resolved each impasse of Andy's misadventures with worldly ladies. Oh that we could have fathers as understanding as Judge Hardy. Or that a boy could have a girlfriend as lovely as Judy Garland or Kathryn Grayson.

And then came that grand moment of revelation and, perhaps, confusion; an instant when life imitates art. The fortuitous event came to pass on January 10, 1942. Our freshman class had entered high school in September of 1941 a few weeks before. On the following Friday afternoon the school newspaper for which I later wrote the weekly humor column, The Beacon, carried the headlines "Mickey Rooney Weds former NNHS Student."

A future member of the class of 1945 had to wonder who was the girl-wife of the story, Ava Gardner? She was a member of the class that had graduated the previous year. The older Potter girl, Virginia, the cheerleader, was her friend and had visited her in California -- she knew and could tell us. And she did.

Ava had arrived from Smithfield, North Carolina, with her mother and father, but soon after, father abandoned them. Mother had to support herself and daughter by running a boarding house. Ava had dated older, and presumably more sophisticated "apprentice boys" from the local shipyard. In Hollywood she was working as a Goldwyn Girl while taking speech lessons in order to erase her southern accent. Sam Goldwyn wanted to cast her in speaking parts. But now Mickey Rooney -- Andy Hardy -- had married the beautiful girl next door, next door to us.

What was real and what was fantasy in all this? As we viewed Ava's magnificent face in wide-screen color close-ups over the years and followed her stormy career, broken marriages, bouts with alcohol, those questions remained unanswered. Fact? Fiction? Obviously, those things that once had seemed to us simple and romantic on our Street of Dreams were more complex.

How blessed were members of the class of 1945 Newport News High School with excellent teachers. They were the silver lining of the clouds of the Great Depression. In more prosperous times many would have been sought by industry, commerce, and the arts. Susie Floyd, who taught science, drove me and two other members her science class in her little automobile 80 miles north to attend the meetings of the Virginia Academy of Science. I understood little of the conference presentations, only that science appeared to be important and interesting.

Gladyes Gamble, who taught English, impressed us with her sophistication. A New Yorker, she spoke of intellectual life in the big city: writers and book publishing. For our writing she stressed the use of concrete verbs rather than "to be" and the active voice rather than the passive.

Our physics teacher was an elderly female physician: Cornelia Segar, M.D. It was rumored that she had lost her life savigs in the Depression and had been forced by fate to find work. Although rather deaf she was an excellent teacher. To explain concepts she sought graphic examples that could be remembered. For the principle of stability, she sought the help of Hasting Hawk largest boy on the football team:"If a player on the opposing team tried to push you over, how would you respond?" At low volume, that she would not hear he answered, "I'd knee him in the nuts." "That's right," she replied with a smile, "you would separate your feet to broaden your base and crouch down to lower your center of gravity." Should a student come up with the answer to a problem with only a number without the unit of measure, she would ask, "One thousand and fifty-four what? Chipmunks?" She read us fan mail from former students thanking her for the useful knowledge she had imparted: inclined planes, pulleys, levers, optics, and convection currents. Many were written by boys then serving in the armed forces.

Classes were large by today's standards: around forty students. Given our gifted teachers, this seems to have made little difference in our learning. Of those class members that I have kept up with many have had distinguished careers. Fred Field, my best school friend, became an electronics engineer, Stella Bicouvaris a physician and professor, Nelson Overton, a judge and Herbert Bateman, a member of the U. S. Congress representing the first district of Virgina.

I would have learned more physics and Latin had I not been distracted by girls in sweaters, pleated skirts, white bobby socks, and saddle Oxfords. As a mere freshman I was enchanted by the junior and senior class girls not only because of their beauty, but for their relative sophistication.

For the school newspaper I wrote a humorous gossip column which often zeroed in on the individual characteristics of my fellows. I am sorry that at times I could be unkind.

On belatedly learning one day that Joseph Hofmann -- the great Polish-American pianist -- was to give a concert in the High School auditorium that evening, I called home to let my mother know that I would not return home until that evening. With no money for a ticket, I stayed in the building after school let out, entered the auditorium and hid there until I could mingle with the music lovers as they began to arrive. At the end of the marvelous performance, I found a program left on a seat, went backstage, and asked Hofmann for an autograph. On thanking him, we shook hands. I could not help myself from glancing at his hands. This verified for me what I had heard: his fingers appeared too short for the demands of the piano. His piano was custom made with narrow keys.

Port cities tend to offer more variety than land-locked ones and Newport News was no exception. Greeks, Italians, Germans, European Jews, and, for us in high school, their children added to the mix. In general, they studied harder than those of us born in the United States. Negro children went a to separate school. This was accepted as part of the normal order of things by white children.

In retrospect, it seems strange that Whites treated Blacks almost as non-humans. After all, religiosity was rampant in the southern states. For Christians the message of Jesus was to love one another. For the Wickes, as for everyone we knew the Saturday night ritual was to take a bath and shine our shoes in preparation for Sunday school and church service. The church organ bursting forth with Bach's church music could be the first live music heard by a child.

Methodist teachings came from the English theologian John Wesley. He held that one's first obligation was to others.

Our little family often walked a few blocks to observe the port of Newport News in action. Coal from the mines of West Virginia was emptied from railroad cars directly into the hatches of ships bound for Europe. Other ships carried scrap iron to Japan. It was loaded by cranes equipped with giant electromagnets. Although we knew it not at the time, this was destined for the Japanese war machine. Ironically, the activity was taking place less than a mile from another: the building of the aircraft carriers at the shipyard.

Our high school years were the war years: 1941 to 45. At the very moment Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese, like the United States I was sound asleep. December 7, 1941 was a Sunday. At 5:30 that morning, as usual, I awakened to the clang of an alarm clock and headed out to deliver the Richmond Times Dispatch as I did each day come rain or shine, snow or hail. I had not realized that by doing so I had joined the exclusive fraternity of the paper boys. In later years I discovered that in any social group of contemporaries one could encounter other males who delivered papers and collected for them on Saturday and who love to swap stories of their adventures in doing so. All of us seemed to have learned about class and caste, generosity and the tight fist, honesty and deceit, in addition to the Protestant work ethic.

I made up for my loss of sleep with a Sunday afternoon nap and thus was the last in the neighborhood to learn that the world had changed that day.

Throughout the war, R.J. worked overtime at the shipyard. He would come home for dinner and return to his drawing board for two or three more hours. Understandably,I saw little of him during those years. Ration-books were issued to allow the purchase of scarce items such as sugar, shoes, and gasoline.

A year before war broke out in Europe with the German invasion of Poland my father purchased his first automobile: a 1940 model Plymouth four-door. We had moved to a neighborhood one block from Buxton Hospital and three miles from downtown. I entered a new school the following fall: Woodrow Wilson.

With the car we could now take vacations far from home. On our first summer vacation we headed south to Mobile to visit my paternal grandmother via Atlanta and Tallahassee. In Georgia we viewed the unfinished, yet imposing, Confederate Memorial Monument on Stone Mountain that depicts three Confederate heroes of the Civil War, President Jefferson Davis and Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. On the wharfs of Mobile I learned how banana boats from Central America were unloaded. Lines of black men each of whom picked up and carried a heavy bunch on his back to an assigned railroad box car. The destination of the box car was matched to the ripeness of the fruit. A square of colored paper was handed to the carrier as he picked up the next bunch. He then knew where to convey it as each box car had been assigned its individual color.

Grandmother served us grits with our breakfast eggs and started each lunch with gumbo soup. Both seemed exotic. The okra in the gumbo was my first.

My father's youngest brother, Julius, taught me the game of chess. I listened to Paul Whiteman records by winding-up the victrola and dropping a cactus needle on the disk.

The following summer we headed north. In state and national parks we slept in two pup-tents into which fitted sleeping-bags with air mattress ordered by mail from L. L. Bean of Freeport, Maine. Ralph and I shared one and our parents the other.

My first glimpse of the lights of New York skyline came as Ralph and I peeked out of our tent. We had pitched it on the campgrounds of the Palisades Interstate Park in New Jersey on a precipice as high above the Hudson River as the Washington Monument we had viewed days earlier.

Being that skyscrapers are best viewed from afar Manhattan's marvels captivated and hypnotized us. For a five-cent nickel one could go anywhere on any of the subway lines. I could have spent the entire day looking at the exotic and sophisticated people carried by the cars. Times Square beckoned. From there a double-decker tour bus conveyed us to Mott Street and Chinatown and to Wall Street and the Battery. As we entered an Italian neighborhood, we viewed the laundry drying outside apartment window. The vista inspired our tour guide to shout, "What you see today they'll wear tomorrow." I vowed to return and spend more time in the Big City.

Continuing north we learned how marble is quarried in Vermont and how lobster is eaten in Maine. There we toured the L. L. Bean store in Freeport and camped in Bar Harbor. A park ranger took us on a boat to an offshore island. While there he reached into a hole in the ground and, like a magician, brought a bird in the had worth more than two in a bush. Birds build nests in trees and would fly away if held in a hand, but this one seemed unique. The ranger said it was called a Leache's Petrel.

With his new car my father could better indulge his passion: the Civil War. His bookcases held fat volumes illustrated by Brady's photos of the War and the many books penned by the prolific author Douglas Southall Freeman among them four-volume biography of Robert E. Lee and he three-volume Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command. Fortress Monroe rests at the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula. It remained in Union hands throughout the War. Years passed before they reached their goal of raching Richmond. Newport News lay nearby. My father would take me along in the car as he explored the battlefields around Williamsburg. He mapped the embankments which he called "readouts" and, after asking permission from a farmer who owned or worked land on the battlefield, walked slowly between the rows of corn as we searched for lead bullets, buttons, and belt-buckles.

On a weekend in 1940 we drove to Manassas, Virginia, near Washington, for the inauguration of the Manassas National Battlefield Park established to preserve the scene of two major Civil War battles in 1861 and 1862. Douglas Southall Freeman presided over the ceremonies. He introduced, among others, three old men who had served in the Confederate Army as drummer boys. One had joined the army at ten years of age. Freeman himself was the son of a Confederate solder.

My father had corresponded with Freeman relative to the number and location of redoubts, but his shyness probably prevented his approaching him on this occasion.

I do believe that my father would have been more content with his life had he become a historian.

Occasionally, R. J. would drive us to Richmond some 60 miles north. Rather than taking the main highway with a speed limit of 55 miles per hour, however, he preferred the back roads along the James River where plantation mansions were located. His favorite was Shirley located about halfway on our journey. Built by slave-holders John Carter and his wife Elizabeth from 1723 to 1738 it still belongs to the Carter family. It featured two-storey porticoes "And,"my father would add,"it was the childhood home of Robert E. Lee's mother, Ann Hill Carter."

Summers during World War II I worked to aid the war effort and from my earnings purchase war bonds. My first employment was with the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation or HRPE. Along with several high-school companions I attended classes after our regular lessons to learn how to become a hatch checker. Our instructors were draftees who had been professionals as civilians. My wages of 72 cents and hour seemed a bonanza. Every time the minute hand went around I had made more than a cent.

Fore, aft, port, and starboard we marked down on our tally sheets as we counted the numbers of canned goods or artillery shells being lifted from the docks and lowered into the hatch of a Liberty Ship. Most of the forces that conducted the North African campaign had sailed from our HRPE. Various full-time regular workers recounted that General Patton had made sure that his personal tank had been lowered down the hatch without a scratch. They attested that he did so with bravura and profanity.

By the time I arrived there shiploads of war prisoners from North Africa were debarking: German and Italian soldiers some with Alpine caps and thumping hob-nailed boots. During a break from work I traded Wing brand cigarettes purchased at ten cents a pack with the soldiers for exotic coins of indeterminate value, buttons, and stamps. These I exchanged through a wire fence until a US soldier guarding the prisoners halted the illicit commerce.

Later I mentioned my adventure to a WAC (Womens Army Corps) who interviewed an Italian high ranking prisoners as they landed. An Italian Army general asked to be placed under the care of his sister in Brooklyn, given his delicate digestive system.

The prisoners arrived on a British ocean liner converted to troop carrier the "Empress of Japan."

It was so fast that rather than sail in a convoy it traveled alone. After taking soldiers to North Africa it brought captives to the United States on return. On the dock I ran into a couple of boys who worked on the ship. They were younger than I, probably sixteen. One gave me a tour of the ship during my lunch time. On hatch covers large Japanese characters had been painted. I knew they were Japanese because of my stamp collecting. My tour guided explained that the previous name of the ship had been "Empress of Japan." Part of the Canadian Pacific Line before the war when the sun never set on the British Empire, it plied between Vancouver on the west coast of Canada and the Orient. Obviously, a ship bearing the name of the enemy would have been embarrassing to the British. Changing it would have gone against the ancient and honored belief of sailors that ill fortune would surely follow. To do so was against wartime regulations as well. How then had the transformation come about? Apparently, only an order from Winston Churchill could bring it about.

Before sailing away the boys offered to stow me away with the assurance that my presence would upset no one. I declined, graciously thanking them, I trust. Had I accepted their offer I would not have been the first Wicke stowaway. Family tradition recounts that our original Wicke ancestor stowed away by hiding in a high coil of rope on the deck of a ship leaving Hamburg, avoiding, thereby, the Franco-Prussian War.

Two other summers I worked at the local shipyard at 68 cents an hour: one summer as a machinist helper and the other as an electrician helper. On my first day at work my foreman met me and directed me to a lathe. "Do you know what this is?" he queried. "No, sir." I admitted. "Good. In that case I don't have to deal with any misconceptions you might have had," he replied. How diplomatic, how kind of him, I felt.

Each workday morn I waited at the bus stop for the three mile ride to the yard. The fare: five cents. One had to punch the time clock before 8 AM. At 4 o'clock we returned the same way, the bus now smelling of sweat and grease. The route took us through the "colored section" where the Negro workers got off. On the bus they were segregated despite having to pay an equal fare. Whites to the front, coloreds to the rear was the rule. Only once did I hear words of protest: from the rear came the lament in a deep voice, "Just 'cause a man's ass is black, he has to ride on the axle."

At the time I had known only two black people: Mary, a woman who came to the apartment to do some ironing on Saturday, and Lawrence, who cut my hair. I knew not their last names nor, it seems, did any other white person. When I had my first haircut after leaving the hospital in my seventh year, Lawrence told me, "We was all pulling for you." I did not know what this meant, but I was struck by its sincerity.

On the job I got to know my fellow workers and learned from them. With the electricians time passed more quickly as we could chat, share opinions and swap jokes as we worked. I liked them. Later in life, given this experience I was baffled in reading Karl Marx's opinion about the nobility of the working class. After investigating I discovered that Marx had never known a worker. Apparently, I was one up on Uncle Karl.

As my high school days ended the war in the European Theater came to a close. Nevertheless, the war in the Pacific continued. Given the tenacity of the Japanese forces it was generally believed that a long bloody conquest island by island was in store for the Allies.

This scenario prompted me to enter the University of Virginia immediately in the summer session and thereby be exempt from the draft when I turned eighteen. Reginald and Mary drove me to Charlottesville and settled me in a room on East Range, part of the original construction by Thomas Jefferson. Classes started and I settled into the daily routine. I lunched at a nearby boarding house. Discussions at the table covered a range of topics from Freud to to physics. On one of my forays into an argument an older student declared that the argument I had put forward was "sophomoric." I had never heard the word but it delighted me as I was only a freshman.

My moment of real triumph at the boarding house table came after a letter I had sent to Life Magazine was published. It commented on a picture in a previous issue showing a man kissing a woman while wearing a hat. I wrote, "Here in the land of the Virginia Gentleman your picture of a man kissing a woman while wearing a hat was greeted with weeping, wailing, and gnashing of teeth." A small copy of the offending picture was appended. One of my professors had used this biblical quotation in a lecture. On of the senior members at the table had brought along a copy of the magazine and read my letter aloud to all. Laughter followed. He asked if any one knew the writer. On learning it was I, his facial expression mirrored incredulity. As an added reward I received several letters from nearby girl schools in praise of it.

On August 6, 1945, only a few weeks after I had enrolled, the radio reported that Hiroshima had been destroyed by an atomic bomb. A what? Something never dreamed of. A second bomb was released over Nagasaki on August 9. Japanese surrender followed on August 15. The War was over. I no longer had to worry about the draft.

The student body of the University consisted overwhelmingly of white males. The few females enrolled were limited to those seeking A B.S. degree in education or chemistry. The School of Nursing at University Hospital as well as nearby all female schools like Mary Baldwin failed to balance the sexual ratio.

Social pressure, which came not only from the older students, but from the faculty as well, meant a dress code: coat and tie, plus a hat for freshmen. The students divided themselves into fraternity members and non-members. These associations were unofficially ranked along class lines. The most prestigious recruited only FFV's -- those belonging to First Families of Virginia: Carters, Madisons, Lees, Byrds as well as the old moneyed wealthy. Jews were accepted only by the two Jewish fraternities. Many freshmen, myself included, joined none.

My next door neighbor, J. Tobias "Toby" Kaufman, became my best friend. His room contained a rented piano and a huge confederate flag on the wall. The flag held no meaning for us other than adding a festive air to the room. Toby became a research scientist at the National Institutes of Health where he carried out significant research on enzymes.

The scene underwent a dramatic transformation the following September of 1946. Millions who had fought in the war had been ushered out of the services. These were offered free education in legislation that became known as the G. I. Bill of Rights. Those that took advantage of this opportunity tended to be older and more mature than those students who had enrolled directly after finishing high school. Many had wives and children.

I was assigned a room-mate whereas I had a private room the previous year. Joe Clancy had served as a machine-gunner on the European front. He limped from having suffered trench-foot. Even in summer he had to wear woolen socks to soften his steps. Each morning he grabbed a cigarette on awaking. Then he opened his eyes.

He spoke little of the war. He mentioned that it was impossible to keep one's feet dry which led to trench-foot. Nevertheless, some officers accused those who limped of being slackers. He added that to be able to move fast on facing the enemy the infantrymen threw away most of their equipment including gas masks and that on one occasion when he had a lone German soldier in the sight of his machine gun he took pity on the defenseless enemy and allowed him run away.

Given our differences in life experiences, Clancy must have thought me puerile. If so, he was right.

My social life in Charlottesville centered on the Methodist Church and at the University on the YMCA. The latter is verified by a notice in the Suffolk News-Herald of September 14, 1946:

Stephen D. Carnes of Suffolk has been elected president of the University of Virginia's Young Men Christian Association, the oldest college YMCA in the country, and will head up the organization during the University's 125th session, which will open on Sept. 30. Vesper services are being conducted in the University chapel by a student committee under joint chairmanship of Carnes and Charles Wicke of Newport News.

This seemed to me fitting as from childhood I had attended church each Sunday with my parents. I believed in doing to others as I wished them to treat me and I believed in charity, abstinence and virginity. On graduation day just after turning twenty I must have been the only one in the 1948 class who remained both a virgin and a teetotaler.

My parents had driven to Charlottesville for my graduation. The ceremony was held out of doors on the University "lawn" -- the term that substituted for "campus" as in other schools and Harvard's "yard." Seated only a few feet from the platform of dignitaries, I could not take my eyes off the University Rector and former Secretary of State, Edward R. Stettinius. His snow-white hair and coal-black eyebrows were set off by a red face. "It must be high blood-pressure," I thought. He died shortly after at forty-nine.

Also on the dais was Admiral William F. Halsey who had retired from the navy the previous year. He had become chairman of the University fund raising campaign. His relationship with the institution went back to 1899 when he had entered medical school. He was destined to die soon after on 20 August 1959.

I had majored in biology as a pre-med student with the intention of becoming a physician. On my graduation I had been accepted by the University of Virginia Medical School.

The summer before entering Medical School I spent in New York where I worked at the Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital on the upper west side of Manhattan. The Hospital had developed a program for pre-med students that would introduce them to what it is to work on the wards. We were called Ward Assistants and numbered about twenty. We soon learned how to take a patient's pulse, blood-pressure, and temperature readings as well as to make beds.

I had returned to the Big Apple and this time without my parents. I was free to explore its wonders. From 165th and Broadway I could hop aboard the A Train and for a nickel go anywhere in the city. On a day off I headed to the south Bronx and Yankee Stadium. My cheap ticket placed me in center-field from where I could almost touch Joe Dimaggio. I could watch Yogi Berra catching behind the plate and see Bobby Brown studying his medical textbooks. I heard years later that at the end of the season Yogi asked Brown how his book turned out.

I thought it odd as I looked around me that I was seated near some well dressed men who, from their appearance, surely could have purchased tickets behind home plate. By the second inning some had removed their shirts and were sunbathing. That explains it I thought. They wish to relax in a more informal way than they could have in the more expensive seats. By the later innings I had perceived that they were betting among themselves. I could hear them proposing fanciful odds. With two outs would the runner on first make it to third base. Ten dollars says he will to your five that he won't.

The Metropolitan Museum beckoned as well. Entry was free and it was practically empty on week days. Rembrandt I had heard of, but Frans Hals I had not. Up close Hals brushwork seemed lackadaisical, but by stepping backward I could view his portraits miraculously transformed into self confident Dutch merchants and their wives.

On Sundays the Museum became crowded. I heard the following conversation there on a Sunday afternoon. Son: "Dad, this must be a picture of Jesus." Dad: "No, can't you read? It's Rex Mundi."

Washington Square on Sunday attracted both chess- and guitar-players. The chess-players studied the sixty-four small squares before them undisturbed by the heartfelt lyrics of "Freiheit" or the children kicking balls and chasing pigeons.

Union Square on 14th Street became alive each evening. Orators praised the Soviet Union, allied with us against fascist Germany and Italy. The Daily Worker was published nearby. Not all the voices came from the left, any one could speak about any thing. Those who had discovered the meaning of it all and wished to share it could find a small audience there.

Times Square beckoned at night. For the price of a beverage one could see and hear the greatest jazz musicians in the world. The Metronome featured the Red Norvo Trio. Norvo's Vibrafone could be heard by all who strolled along the east side of Broadway near 44th Street. At a new venue called Bop City I caught Louis Armstrong and Jack Teagarden As I climbed the stairs that led up to Bop City, I was thinking it odd that these traditional jazz men were booked at a place bearing a name derived from Bee-bop. But there the two old-timers were with a young and talented bassist. They were finishing a set. Armstrong was sweating and moving a giant white handkerchief from trumpet to his face and back again. It was hard to believe that I was seeing them and hearing them play the old standard "Do You Know what it Means to Miss New Orleans?"

After their set had finished, a musician of whom I had never heard was introduced to loud applause. Obviously, this was the group that the, to me, sophisticated audience had come to see: George Shearing and his quintet. He came to his grand piano wearing dark glasses arm-in-arm with a young lady that Shearing introduced as Margie Hyams. She played vibraphone along with a drummer, guitarist and bassist. What is their relationship, I wondered. To present themselves as so close together must mean something. I was probably the only one there that did not know that Shearing was blind. Still none of us knew that he soon would compose the jazz standard "Lullaby of Birdland" or that years later he would be knighted. With great animation Shearing produced incredible music as he smiled and moved his head to one side and the other.

In the fall I returned to Charlottesville as a member of the first year class in the School of Medicine. Having completed my college courses in three years I was among the youngest of the class. I did well in my first semester, but by the second I had lost interest in my studies. No longer on East Range but assigned a room far from my few friends, I had become reclusive and depressed. Just as Admiral Halsey fifty years before, I had learned was that medicine was not for me;I lacked the temperment. My romantic idea of becoming a medical missionary to Korea I derived from the sponsor of the Methodist Youth Group, who had been a missionary. I was certain that God would see me through. Daydreaming instead of studying, I was unprepared for final examinations. God had failed to help me.

After a short visit with my parents in Newport News, I returned to New York and Columbia-Presbyterian desirous of helping my fellow man as an orderly. The job entitled me to live rent-free in an old building belonging to the Columbia Presbyterian complex at 165th and Riverside Drive. Some referred to it as "The Abandoned Insane Asylum." Whether this designation was historically accurate it was what New York social climbers call "a good address" and from the third and top floor, to which I was assigned, a spectacular view appeared just after sunset. One could see the lights of the George Washington Bridge 14 blocks to the north as well as those of Fort Lee, New Jersey, on the other side of the Hudson River.

After settling in, I enrolled in art classes at the Art Students League.

From the Hospital I could take the A-Train at 168th Street and Broadway, journey south to Columbus Circle and walk a few blocks to 215 West 57th Street. Having won prizes in drawing and painting in school and having learned something of human anatomy, I thought I might become a medical illustrator. In choosing a teacher at the League I passed over the abstractionists and found a realist: Frank Reilly.

If we accept Alfred North Whitehead's definition of nature as what we perceive through the senses, Frank Reilly's most notable feature was his perception. His curiosity about how things looked led him to generalize not only about the human figure, but also about trees, distant mountains, and sunsets. The characteristics of human creations he noted as well be they drapery or bricks, telephone poles or shoes.

If you are painting a distant mountain in a landscape in your studio, don't make it up, he advised. Pick up some rocks and copy their shapes and shadows.

If you see an imposing tree, take a picture of it. You may need it later.

Don't put heavy outlines around your depictions. In nature objects are never outlined.

Drapery does not curve like that of early early Greek sculpture, rather it falls in linear patterns, he advised. In his apartment, he recounted, he would pile up a few books on his coffee-table and throw a big handkerchief over them. Then you could see how the cloth shapes itself relative to the books under it. In order to demonstrate this principle he sometimes would ask the nude model to sit in a chair in her penultimate pose, then to assume the same pose after getting dressed.

I once asked him to look at a portrait I was doing. Kind in his criticism, he pointed out that I had placed shadows of the same depth on both sides of the nose: something that almost never happens in reality. He quickly and kindly added, "I like the way you rounded out the forehead."

On Saturday mornings at the League a model was provided in one of the studios where a member could sketch without paying a fee. As I was working nights I could attend. On one such occasion a striking girl in a black dress sat down beside me. I would steal a glance when she crossed her nylon-covered legs making s swishing sound. How odd you are I thought. A completely naked woman is a few feet in front of you and you are more interested in one fully clothed.

During the model's break, we chatted and I asked if she would have lunch with me. While eating I asked her if she had seen "A Streetcar Named Desire" with Marlon Brando -- the Broadway hit of the season. She answered no, but that she wanted to see it, adding, "It's sold out, Standing Room Only" We ended up attending the Saturday matinee at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre: SRO. Brando's powerful performance captivated the audience. To have seen Brando at the top of his career, even though it was the beginning, is a memory that has lasted a lifetime. Nor can one forget Jessica Tandy, Kim Hunter and Karl Malden who could not have been better.

My new friend's name was Epstein, but I can no longer remember her first name. What I do recall was that she lived in West End Avenue and that her uncle was the sculptor Jacob Epstein. I enjoyed her company in the weeks that followed. That the brothers Epstein were dentist and sculptor held significance: both had inherited an aptitude for working in three dimensions.

Often I was assigned the night shift at the Hospital. Then Manhattan became mine during daytime. The Island offered more things than museums and ball games. When as 1949 was ending the sensational second perjury trial of Alger Hiss was in the headlines. Out of curiosity I journeyed to the Federal Courthouse in lower Manhattan to witness the arrival of Alger Hiss and his wife Priscilla. I was impressed by their aristocratic mien: well dressed and looking straight ahead as they ascended the steps. I did not see Whittaker Chambers, nor was I seeking him out. My understanding of the trial was almost nil. Only in later life did I delve into the details and read Chambers' "Witness" (1952). The affair was to ligitimise the Cold War and to propel Congressman Richard Nixon of Orange County, California, into the national spotlight.

Each patient with whom I came in contact was unique. A young man about my age suffered paralysis with no feeling or movement below his neck. He had dived into a shallow irrigation ditch in Texas and severed his spinal cord a neck level. Like a hot dog in a bun, he was strapped in an apparatus called a Striker Frame. It allowed the patient to be turned without disrupting the alignment of the neck -- upward, downward, or to either side. I tried to cheer him up with nonsensical stories at which he laughed -- perhaps out of politeness. He could read a book when face down by turning pages with his mouth, each page having a thread attached to its corner. Eventually, he died of pneumonia.

Another was a pleasent piano player with syphilis. He related that he played in a show band. He met and married a chorus girl from whom he was infected with syphilis The treatment that he underwent consisted of heating his body to a temperature that would kill Treponema bacteria without killing him.

I could be assigned to any part of the Center each time I came to work; often at midnight. Among my most horrendous memories are those of the Emergency Room and the Neurological Institution. The victims of automobile accidents brought to the Emergency Room engendered in me a fear of what an impact can do. Americans are said to have a love affair with the automobile. I am not among them.

In the Neurological Institution I became acquainted with brain cancer. It seemed to me almost always the same scenario. A male patient -- I was assigned to male wards -- had a headache for the last few days. Aspirin failed to lessened the pain. He would be diagnosed by a spinal tap and an x-ray. A tumor would be detected. Surgery was performed. After having survived the operation, he would be visited by his wife and children. Ushered to his bedside they tried to speak to him only to learn that he had been transformed. He had become a vegetable.

The most disheartening patients in Columbia-Presbyterian I encountered in the Childrens Hospital -- many with cancer. This experience remains too terrible for me to recount after more than a half-century. It forced me to ask myself how this could be if the universe was directed by a loving God.

No one that I wrote to -- including the director of the Methodist youth group in Charlottesville -- or talked to about my problem could come up with a satisfying answer. After much thought, I no longer could believe in a monotheistic deity. I concurred with George Orwell's dictum: the idea of religion is "nonsensical."

Mother Nature became my mistress. Not loving me, not hating me, she demonstrated only indifference. She remains difficult to live with, but she tells no lies. Her indifference became my freedom. I was transformed into a recovering Christian. As the Bible had promised, "Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free" - John 8:32. To that I added that one must know the truth before he -- newspeak "they" -- can find happiness.

In the evening of my first day of freedom, I felt elated enough to walk two blocks north on Broadway from Columbia-Presbyterian and order a beer at a neighborhood tavern. On entering such a sanctuary for the first time, I felt comradeship. Obviously the patrons knew one another. After ordering a glass of beer I stood at the bar and watched, on the wall behind it, my first television program ever: "The Texaco Star Theater" featuring Milton Berle, "Uncle Miltie, the Thief of Bad Gag," and America's first TV star. He paddled across the back-and-white screen in a wheeled canoe. With no idea that I was slowly sipping the bartender commanded me, "Drink up!" He had no idea that I was slowly sipping the first one of my life; that I was shedding my teetotaler status. On the other hand, I had no idea that he was offering me a free drink. For him I was a newcomer in the neighborhood. Suddenly, it dawned on me that life was there to be enjoyed.

Before I had left the University of Virginia for the last time, I stopped by the YMCA office to say good bye. On hearing that I was off to New York, Gloria, the secretary, mentioned that she was from New York and would be there in a month or so. She gave me a card bearing an address in the West 80's and a phone number. This sounded strange since she was married to a University student whom I had never met.

Once settled in New York, I phoned Gloria who instructed me to take the A-train and and get off near 38 street. She was living there with her married sister in a brownstone.

Gloria, small, slender, and pretty, looked younger than I although two or three years older. She told me that she was working for an importer of newsprint from Canada. She mentioned that she was now divorced. Her voice was matter of fact and her story criptic. She did not complain never mentioned it again. We began to go out together. She liked the museums and the movies. One Saturday afternoon as we strolled by Bloomingdale's she spied a a jacket and pleated woolen skirt of red plaid. Out of curiosity, we went inside to ask the price. An obviously experienced saleslady studied Gloria before she gave us the cost adding, "And we have it in a size eight." Given Gloria's pleasing figure, I thought to myself, "Eight sounds like a wonderful size."

Weeks passed as we enhanced our knowledge not only of art history and motion pictures, but of one another. Our favorite museum was the Metropolitan where neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova's "Psyche Revived by the Kiss of Love" became our focal point.

"Psyche Revived by the Kiss of Love" 1787

One Saturday night we happened on Sammy's Bowery Follies at Bowery and 3rd Street. "Sammy" was Sammy Fuchs, the owner, an Austrian refugee. The offbeat nightclub known as "the poor man's Stork Club." Since I was a poor young man I felt we belonged there. Sammy charged a minimum which meant that the beer flowed more than our ability to consume it. As we staggered out the waiter said, "Sir, aren't you forgetting the waiter?" "No," I answered, "You can have all the bottles that we couldn't drink." It was somewhat embarrassing to leave that way, but we had only a few nickels for the subway.

It had been an auspicious evening. Gloria had agreed to help me loose my virginity.

On the following weekend, we met in Times Square at a time and place agreed upon. I had slept little the night before so excited as I was at the prospect of what awaited. I carried a suitcase within which rested a bottle of effervescent, sparkling Burgundy. I had no idea that the French filled their worst wine with bubbles. I assumed that one should carry a suitcase when registering at the Hotel Taft in order to avoid suspicion that we were unwed. In retrospect, we must have looked like two innocents abroad. As Gloria said about herself: "Don't I look like Little Miss Prim?"

We spent the wonderful weekend in bed. Only to grab a bite now and then on Times Square did we leave our nest. No longer a virgin, I had found heaven on earth.

All was going well. My drawing skills were developing. I had enrolled in Reginald Marsh's class while continuing to study with Frank Reilly. Marsh was another excellent teacher, warm, kind, insightful. My fascination with New York continued to grow. Then, suddenly, unexpectly, my dream ended.

On June 25, 1950 when it happened I paid little attention to Korea being invaded. Half way around the world, how could it affect me? Weeks later, the answer to this question came in the form of a letter to me from the draft board in Newport News. I filled out a request asking to take my physical exam in New York. My petition having been granted, I showed up on time in lower Manhattan. The first order of business turned out to be an intelligence test consisting of twenty or so problems. They seemed less than daunting and, not being highly motivated, I finished it within 10 or 12 minutes and handed it in to the army sargent who sat at the table in front of what appeared a classroom. He checked my test immediately and showed it to the corporal seated beside him. They whispered. The corporal left only to return with a lieutenant, who rechecked my test from the list of correct answers. Every one else in the room was still at work. I was pointed out to the officer. I had put down the correct solutions to all of the problems. From their reactions, it would appear that my feat was something that seldom happened.

I felt certain that because of my lungs and eyes, I would be rejected and classified 4-F, as that category was designated. For the physical exam we had disrobed. With the first doctor who looked at me I called attention to the scar on my back from my childhood surgery, but to no avail. Lined up ahead of me receiving all the attention was a Jewish divinity student wearing only a wide-brimmed black hat from which long curls fell. His chalk-white body held an anomalous heart that the doctors were looking at with fascination. But my lungs? The stethoscope pronounced them hale and hearty. And my myopic eyes? A thick lens remedied them.

As I walked out of the big room last doctor stamped my medical report saying as he did so: "You are class C. That means you can be drafted, but you won't be allowed to fight. No combat for you." And so it was to be.

I said my good-byes to those with whom I worked with me at Columbian-Presbyterian, to my companions at the Art Students' League.When, after calling ahead, I dropped by to see Gloria, her brother-in-law let me in. He told me that Gloria had gone out because she was too distraught about my leaving to see me.

Returning to Newport News, I spent a few days with my parents. In the pre-dawn darkness of the appointed day, the 19th of February 1951, I said farewell to my father at the railroad station. A member of the draft board handed me a stack of orders and put me in charge of the group of a dozen or so draftees. I was so entrusted because of having made the top score on the test given in New York. Several of the group I had known in high-school. We were told to memorize our new serial numbers on our trip to Fort George E. Meade, Maryland. From that day to this I can recite it on command.

After a few days in Fort Meade, I learned that I would undergo a six month training program at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina. On satisfactory completion I would earn the designation of "infantry replacement." This came as somewhat of a shock. I had been assured that my myopia would keep me out of combat. Only later did I learned that because US troops had almost driven into the sea at the start of the conflict. One reason for this was that the cooks and musicians and their ilk had little weapons training. Thereafter, everyone entering the army was required to undergo six months of basic training.

I had entered the army at a historic moment. Under the leadership of President Harry Truman and Chief of Staff Dwight Eisenhower it was undergoing racial integration. Up until then black men had to serve their country in all-black units.

My opportunity to view this process was as if I were anthropologist: as a participant observer at first hand. Moreover, the setting was the deep segregated south.

The Eighth "Golden Arrow" Division to which I was assigned had seen 10 straight months of combat in World War II in Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, and Central European campaigns.

At the same time the Thirty-first Infantry Division, dubbed the "Dixie Division" because its members were white males from Alabama and Missisippi, was undergoing training at Fort Jackson. It had seen action in the South Pacific during World War II. Apparently, it had become a division of the National Guard. As we marched out to the firing ranges each morning, our salt-and-pepper company would hear cat calls and whistles from the lily-whites of the 31st which we answered branding them the "Dixie Dahlin's" and "White Crackers."

On the military base the "Golden Arrow" solders were living in a desegregated society. Off base in Columbia, South Carolina's capital, we were in a completely segregated society.

At the age of 22 and for the first time in my life, I had the opportunity to know Negroes at close range and on equal terms.

Our company of 200 soldiers showed more disparate qualities than race. Many were volunteers rather than draftees, most had only recently been graduated from high-school and three of four years younger than I. Many had signed up to continue training in order to become paratroopers. The most eager of these chose to sleep at the higher level our two-tiered bunks. On awakening, they stood up and jumped to the floor as if landing in a parachute.

It seemed that I was the only college graduate in our barracks. I defended myself against sergents seeking to intimidate me by transforming myself into a pedant. The following dialogue is an example. Sergent: "Where was you at?" Me (with feigned sincerity): "What? Oh, you mean to say 'were.' 'Was' is third person. The correct form of the verb 'to be' in the your sentence is in the second person 'were.' Moreover, you shouldn't end the sentence with the preposition 'at' or any preposition whatsoever." They tended to let me alone after that.

It turned out that I was not the only college grad there after all. His name was Clarence Varner. He was thin and a bit stooped. Like me, he was a draftee and wore glasses. Unlike me he was a Negro. It was great to find someone with whom I could talk, who read books, who knew who Beethoven was, and Bartok, and Joseph Stalin.

We could converse while eating in the mess hall, or resting after a long march. We we could not do was to eat together off base. Columbia, South Carolina, was completely segregated by race.

I asked Clarence whether he thought this situation strange. He answered that he had a way to circumvent the rules. On our next opportunity to go off base we left together. Clarence had graduated from a Negro College in the south and had been a fraternity member. He had friends in Columbia. We took a cab to a fraternity house at one of Columbia's Colleges. He gave the secret handshake to the brother who had opened the door. We were both in uniform since we had been ordered to send home all of our civilian garb during our training. It was a Friday night: party time. Girls were there, real live girls, how wonderful.

On another outing, Clarence had been invited to dinner with a college friend and his new wife. He coached football at a Black high-school in Columbia. The newlyweds made delightful and most gracious pair.

Clarence turned out to be a member of the Negro Elks Lodge -- a real joiner. We stopped by the local Lodge one evening and ordered scotch on the rocks. Only a few members were present and all were much older than we. They seemed grave and somewhat conservative in dress and demeanor. When the waiter returned he carried but one scotch and served it to Clarence. He said that they could not serve me. This upset Clarence, but I intervened telling both him and the waiter that "turnabout is fair play." I must have been the first white person to have entered the private domain and the members didn't know what to do with me. Perhaps they thought I would become rowdy or worse under the influence of fire water.

After one of our sojourns to Columbia, we took a cab back to Fort Jackson. The hour was somewhat late. On entering the base we were stopped by a military guard. He explored the rear seat of the cab with an enormous flash light. As he did so, we could see his shoulder which bore the double D patch of the Dixie Division. He carefully observed our faces: one beige, one white. He must have seen our Golden Arrow shoulder patches as well. Not a word was spoken as he continued to observe. Time passed. Finally, he waved us on. He would have a strange story to relate in the mess-hall at breakfast.

I corresponded with Clarence for a few years after the army. He entered a Presbyterian monastery. I had no idea that Presbyterians had such things.

Early each morning after breakfast and inspection we marched out to a different venue to practice with different weapon, always carrying our M-1 rifles.

Like beasts of burden, we knew not where we were going or what weapon awaited us there. It could be hand-grenades or 50 millimeter machine-guns; mortars or bazookas we were to learn to employ. The sandy soil into which our boots would sink with each step made marching difficult. To relieve the monotony we would chant in march-time, "I met a gal and she was willing. Now I'm taking penicillin. Sound off! Sound off! One, two, three, four. One, two,three four."

Had I not been informed that I would never be engaged in combat I might have taken this more seriously. Of greater concern, I did not want to become brutalized by the process. I saw this happening to many of my comrads. They were developing a pecking order.

I was puzzled that we were told nothing about why the US was fighting in South Korea. As with the US mission in Iraq as I write, it seemed to change. The goal was held to be the unification of Korea, repel aggression, secure our forces, and finally to secure an armistice. The sole reason given for why we were learning how to fight was so that we would "not let down our buddies." (Another parallel with present day training and fighting.) Frankly, I found it difficult to think of my fellow trainees as buddies.

Shortly before the invasion, the U.S. Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, had given a speech in which he defined the "defense perimeter" to Communist threats in Asia. Acheson failed to list South Korea in his list. Could this have resulted in the invasion from the north?