Once secretive about her famous brother, Connie Lemos co-organized a rock n' roll concert in tribute to Ritchie Valens

By DEAN PATON

Pinnacle Staff Writer

February 10, 2005

Most people remember February 3, 1959 as the day the music died, but for Connie Lemos of Hollister it's the day she lost her brother, Ritchie Valens, the late-1950s rock ‘n roll icon.

Ritchie is best known for his adaptation of the Mexican folk song "La Bamba."

He died in an Iowa plane crash along with Buddy Holly and J.P. Richardson, a.k.a. the Big Bopper, changing the course of American pop culture overnight.

For decades Connie was unable to completely face what that day meant for her family and a 17-year-old brother she would never get to know as an adult. She was only 8 when his star faded into legend. The few precious memories she had of her brother, of him babysitting her, of her sitting in the car listening to his music with her mom and the beautiful home he bought them in Pacoima, Calif. in a white middle-class neighborhood – those memories were almost blocked out forever.

That Connie couldn't listen to her brother's music until 1987, the year the movie "La Bamba" came out, seems almost impossible to imagine, looking around her Ridgemark home.

The walls are covered with still shots from the movie set, autographs from the likes of Don King, Clint Eastwood and Lou Diamond Phillips and a picture from the 2001 induction ceremony of Valens into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Ricky Martin hosted that event, and Connie and her husband John are standing next to him in a framed picture that stands guard over their fireplace. Also on the wall next to their pool table is one of those gold albums you see dozens of at the Hard Rock Café. Next to that is Ritchie's framed image on the 29-cent stamp.

Juxtapose these sentimental items with the anecdote of Connie joyriding down a freeway in her 20s, sitting in the backseat. And just imagine the look on her face when a friend popped in a tape and on came her brother's music. Connie froze. None of her friends knew until then that she was the sister of the late Ritchie Valens.

"Twenty years ago I couldn't have sat in a room like this," she said, gesturing to the walls of her home. "I once worked at a dental office for five years and never said a word about Ritchie. One day a coworker of mine just turned to me out of nowhere and asked, ‘Is Ritchie Valens your brother?' and I said, ‘Yes."

"Well, why didn't you say something?" the coworker asked her.

"You never asked," Connie told her.

For Connie it all has a surreal quality: her brother, the movie about him (in which her whole family had cameo appearances), and the chance it gave her to taste just a bit of fame.

"You'd have a hard time convincing me it was not all a dream," she said. Where La Bamba Left Off

For Connie and her remaining two brothers and sister, February 3 was more than a date Don McLean immortalized with his song "The Day the Music Died." For those who don't recall the lyrics, here's the chorus:

"Bye bye Miss American Pie,

Drove my Chevy to the levee but the levee was dry,

Them good ole boys were drinkin' whiskey and rye,

Singing "This'll be the day that I die,

This'll be the day that I die."

February 3 became the day each year that her family tiptoed around the house, her mother sadly listening, over and over, to the 33 songs Ritchie recorded in his brief eight-month career. The other day they tiptoed around the house was May 13, Ritchie's birthday.

In the movie, Ritchie Valens takes his family out of fruit-picking poverty and buys them a new house in Southern California. Real life was that way, too, but what the movie didn't say was that after Ritchie died, the family sunk back into poverty.

Connie's mother, also named Connie, had a nervous breakdown. She left her children in the care of relatives for a year and moved with her son Bob up to Watsonville. Eventually, her mother sent for the children. Money seemed to be the last thing on anyone's mind.

They switched their nice TV, stereo and new furniture – all luxurious amenities back in the 50s – for apple crates to use as chairs and a giant industrial spool for a kitchen table. The Valenzuela family – Ritchie Valens is a name created by a record producer so that no one would know he was Latino - soon found they didn't quite fit into Watsonville's neat little categories.

There were middle class whites, migrant workers who didn't speak a word of English, and then there were the Valenzuelas. They had already lived in the U.S. for more than a generation, and while there were a few such families around none had tasted fame, and gone from rags to riches to rags.

The trauma of having her household turned upside down by rock ‘n roll made growing up tough for Connie.

The pain faded with time and Connie established her own identity, marrying a general manager of a car dealership from Salinas and having her own children. After the day the music died, rock ‘n roll would lose its innocent hymns to morph into an anti-war platform that drove the 1960s counterculture revolution. Acts like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix replaced the feel-good rhythms of the previous decade.

Then in 1984 a movie producer named Taylor Hackford approached Connie's mother. Hackford wasn't the first. Many people had wanted to tell the Ritchie Valens story over the years, but Connie's mother trusted her intuition and therefore never trusted them. Hackford seemed different somehow, not the product of a Hollywood image assembly line. Connie's mother insisted the story be truthful, and that the family have its place on the movie set.

"If I'm going to trust you with my son's story, you're going to do right by our family," is what Connie's mother said to Hackford.

"You know what surprised me?" Connie said. "He kept his promise." Connie played a cameo as a migrant worker; her niece played the role of Connie's sister, Irma. For the first time, Connie learned what the rest of her family had been doing on February 3, 1959. The man who wrote the script and directed the film, Luis Valdez, has long had San Benito County roots through his founding of the San Juan Bautista-based El Teatro Campesino. Part of the movie was even shot on Southside Road.

Until Valdez talked to family members and wrote the script, no one in the family had discussed how brother Bob was working on his car when he heard the radio report, or how Connie learned the news walking home from school.

Connie learned to appreciate what her brother's legend, and his stardom, meant in the larger scheme of pop culture. Her mother finally seemed at peace and passed away in 1987, the year the movie came out.

Once the movie debuted, Connie and her husband soon found themselves being chauffeured to all sorts of celebratory events such as the premier and a key ceremony in Sacramento in which she met Ritchie's teenage love, Donna.

Around that time, the family finally stood up to Ritchie's record producers to demand they share in the financial proceeds. The movie had one other positive effect. It minted more than one star's career. Somehow, Connie thought this would have been the way her brother would have wanted things. "It was Ritchie opening doors all over again," she said.

Rock n Roll 101

Last November, Connie received a phone call at her Hollister home from brother Mario, informing her the family had planned something special for the 46th anniversary: a rock concert.

"Whose big idea was this?" Connie asked, a little anxious and annoyed. "Are you crazy?"

Connie was just about settled in Hollister, where she had moved the year before. A Salinas shooting in Connie's favorite department store, Macy's, prompted her husband and Connie to search for a new home. She has long had a connection to San Benito County and used to own a boutique in San Juan Bautista called Once Again.

Hollister's weather and the friendliness of neighbors in Ridgemark proved a pleasant change from gang-ridden Salinas.

The last thing she wanted was to take part in filling an 800-seat auditorium in Watsonville for a lineup of ‘50s rock ‘n roll cover bands in a reenactment of the Winter Party Dance Tour, Ritchie's last.

But that's just what fate had in mind. In the movie, it was Ritchie's mother who went to bat for her son before he became famous, finding him a venue at an American Legion Hall and driving around in a truck promoting the event with a loudspeaker. Fate brought a record producer to the American Legion Hall that night and this is how Ritchie was discovered.

Like her mother half a century ago, Connie soon found her house covered with posters and piles of t-shirts. The family approached local radio stations to do promotional spots. Connie canvassed Hollister with the posters she designed. They still hang in places like the Hard Times Café. All her new Hollister friends bought tickets.

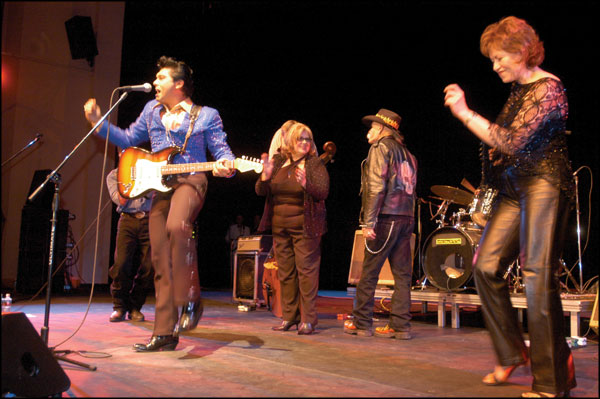

They lined up a Buddy Holly, a Big Bopper and a Ritchie look-alike for entertainment. Last Saturday, every seat in the Henry Mello Center was sold out. The crowd stayed in their seats until Ritchie's look-alike walked out onto stage and began playing "La Bamba."

"You know something folks?" he said. "La Bamba is Watsonville's National Anthem and everyone's got to stand up for the National Anthem."

Connie's brother played harmonica during the song, and soon Ritchie's likeness called up the rest of the family to the stage. He pointed to the audience and got them to sing along.

Looking out into a crowd of 800 dancing people, Connie clapped to the beat, smiling. Though Connie, her family and Ritchie were deprived of a full life in each other's company, she has come to terms with it. She has always known that the lesson of her brother's passing is to live each day to its fullest, to squeeze as much joy as you can out of every good moment, because in the next you might not be there.

Her brother will always be a source of inspiration, a spiritual marker on life's road to guide her.

"Where were you when you were 17? Where was I when I was 17?" she asked. "Ritchie was out making rock ‘n roll."

Click Here For Ritchie Valens Articles Directory

Click Here For Ritchie Valens Directory